Fundamentals

You may have a persistent feeling that something is fundamentally misaligned within your body. It could manifest as a quiet drain on your energy, a subtle fog clouding your thoughts, or a frustrating inability to feel like yourself. This experience, this sense of being disconnected from your own vitality, is a valid and important signal.

It points toward a disruption in the body’s most intricate communication networks. We can begin to understand this by examining one of the most powerful of these systems ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the central command for your hormonal health, a biological triad that dictates much of your reproductive capacity, your energy, your mood, and your overall sense of well-being. Understanding its function is the first step toward reclaiming your biological sovereignty.

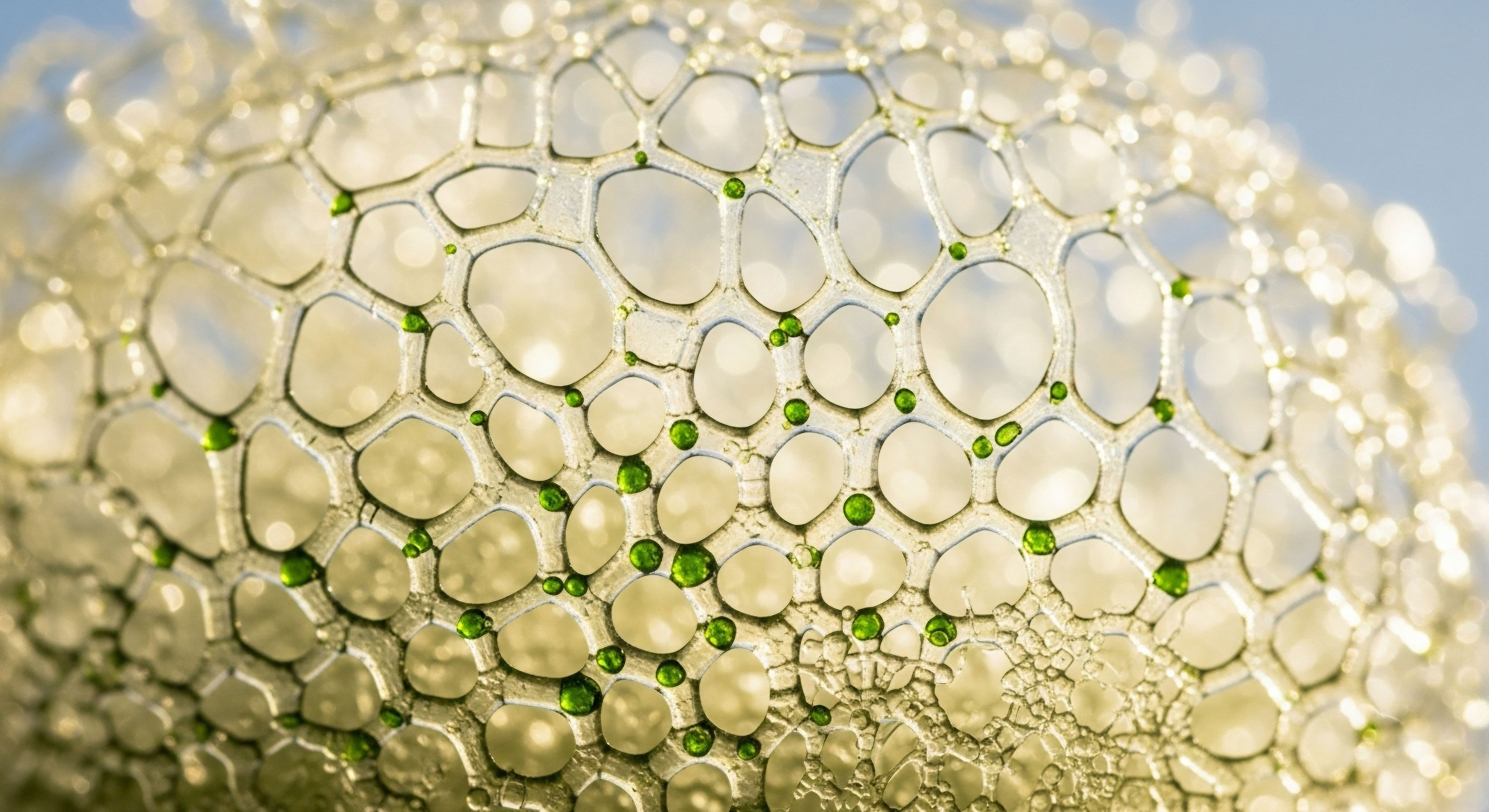

The HPG axis is a sophisticated feedback loop, a constant conversation between three distinct endocrine glands. It begins in the brain, in a region called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus acts as the system’s initiator, releasing a crucial signaling molecule, Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), in a rhythmic, pulsatile manner.

This pulse is the starting gun for the entire sequence. GnRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the body’s master gland, and instructs it to release two other hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then enter the bloodstream and travel to their final destination ∞ the gonads, which are the testes in men and the ovaries in women.

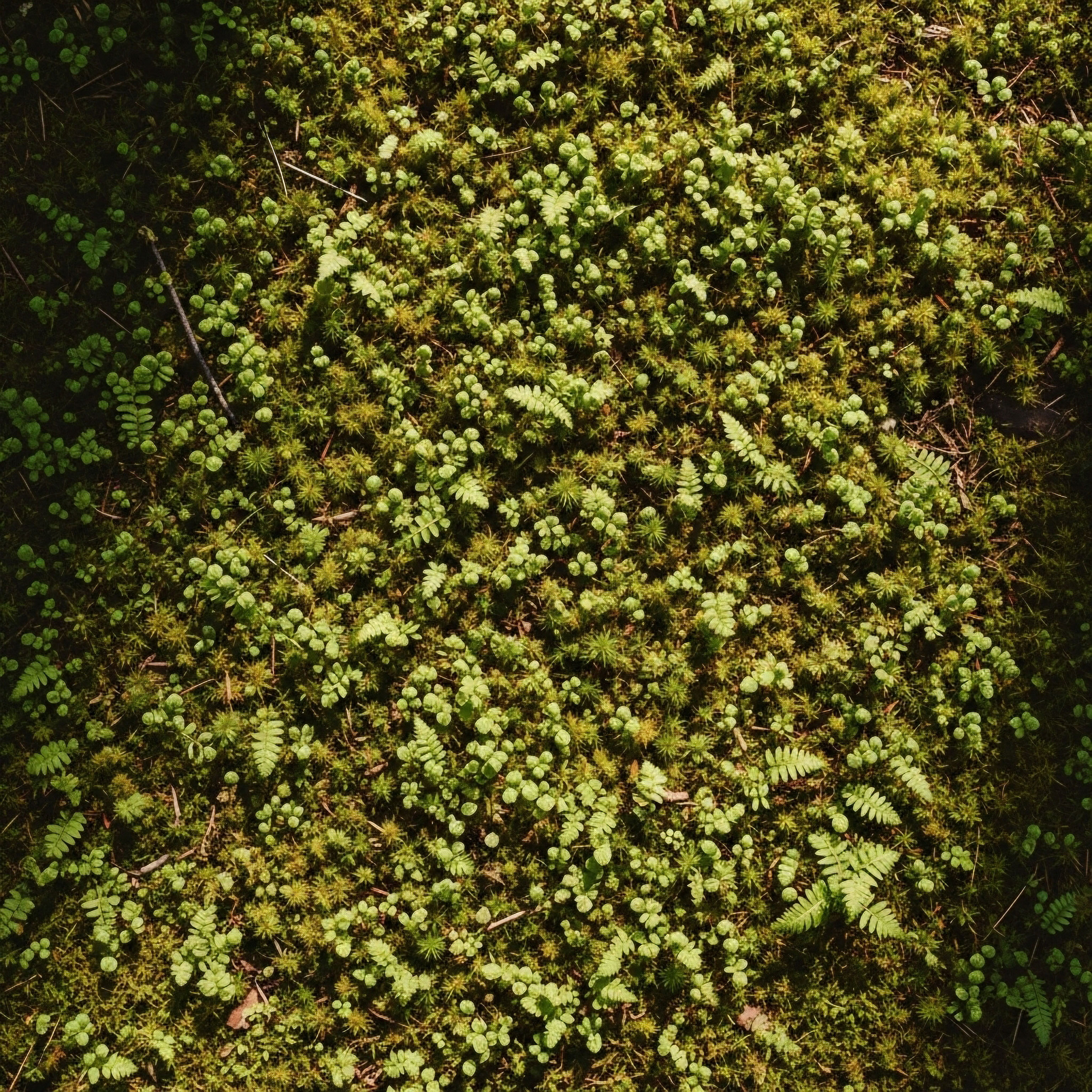

The HPG axis functions as a precise hormonal cascade, beginning in the brain and extending to the gonads to regulate vitality and reproduction.

Upon receiving the signals from LH and FSH, the gonads perform their primary functions. In men, LH stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone, the principal male androgen. FSH, working alongside testosterone, is essential for sperm production. In women, the process is more cyclical.

FSH stimulates the growth of ovarian follicles, each containing an egg. As the follicles mature, they produce estrogen. A surge of LH then triggers ovulation, the release of a mature egg, and prompts the remaining follicular structure to produce progesterone.

These powerful steroid hormones, testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, then travel throughout the body, influencing everything from muscle mass and bone density to mood and libido. They also send feedback signals back to the brain, telling the hypothalamus and pituitary to adjust their release of GnRH, LH, and FSH, thus completing the loop. This self-regulating mechanism ensures the system remains in a state of dynamic equilibrium.

What Is HPG Axis Suppression?

HPG axis suppression occurs when this carefully orchestrated conversation is silenced. The primary cause is often the introduction of external, or exogenous, hormones. When a person undergoes Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) or uses androgenic anabolic steroids, the brain detects high levels of these hormones in the blood.

Perceiving an abundance, the hypothalamus and pituitary halt their own production of GnRH, LH, and FSH. The natural signaling cascade ceases, and the gonads, no longer receiving instructions from the brain, dramatically reduce or stop their own production of testosterone and sperm in men, or modulate ovarian function in women.

This shutdown is a natural, protective mechanism; the body is simply trying to maintain balance. Other factors, such as extreme chronic stress, severe caloric restriction, or certain medical conditions, can also suppress this axis by disrupting the initial GnRH pulse from the hypothalamus.

Defining Incomplete Recovery

Following the cessation of exogenous hormones or the removal of a stressor, the body should ideally restart its own hormonal production. A post-cycle therapy (PCT) protocol, often involving medications like Clomid, Gonadorelin, or Tamoxifen, is designed to stimulate this process.

Complete recovery means the HPG axis successfully re-establishes its pulsatile signaling, and the gonads resume their normal function, restoring endogenous hormone levels and fertility. Incomplete recovery, however, describes a state where this restart falters. The axis may partially reactivate, but it fails to achieve its previous level of function.

LH and FSH signals may remain weak, testosterone or estrogen levels may stay chronically low, and symptoms of hormonal deficiency persist long after the suppressive agent has been removed. This state of sustained dysfunction is where the most serious long-term implications begin to surface, creating a cascade of systemic health issues that extend far beyond reproductive health alone.

Intermediate

When the HPG axis fails to fully recover, the body is left in a state of prolonged hormonal insufficiency. This is a systemic issue, creating ripples that touch nearly every aspect of human physiology. The consequences are a direct result of the body being deprived of the adequate levels of testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone required for optimal function.

The lived experience is one of chronic symptoms that can be difficult to connect, yet they all trace back to this central endocrine failure. Examining these implications reveals how interconnected our biological systems truly are, and why restoring this axis is foundational to long-term health.

Metabolic Dysregulation a Silent Epidemic

One of the most profound consequences of incomplete HPG axis recovery is the progressive disruption of metabolic health. Sex hormones are powerful regulators of how the body processes and stores energy. When their signals are weak or absent, the body’s ability to manage blood sugar and fat metabolism becomes impaired.

The Onset of Insulin Resistance

Testosterone and estrogen play a direct role in promoting insulin sensitivity. They help muscle and liver cells respond efficiently to insulin, the hormone responsible for ushering glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells for energy. In a state of hormonal deficiency, cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal.

The pancreas compensates by producing even more insulin to try and manage blood glucose, a condition known as hyperinsulinemia. This cycle of insulin resistance is a precursor to type 2 diabetes and is intimately linked to increased inflammation and cardiovascular strain. The fatigue and cravings for sugar that often accompany low hormonal states are a direct symptom of this inefficient energy management at the cellular level.

Adipose Tissue and Body Composition Changes

A dysfunctional HPG axis fundamentally alters body composition. Testosterone is a key driver of lean muscle mass, while both testosterone and estrogen influence where the body stores fat. With chronically low testosterone, men find it increasingly difficult to build or maintain muscle, a condition called sarcopenia.

Simultaneously, the body’s tendency to store visceral fat ∞ the metabolically active and inflammatory fat around the organs ∞ increases. In women, the loss of estrogen and the relative imbalance with testosterone following menopause or during HPO axis dysfunction can also lead to a shift in fat storage from the hips and thighs to the abdomen. This change in the lean mass to fat mass ratio further exacerbates insulin resistance and creates a pro-inflammatory internal environment.

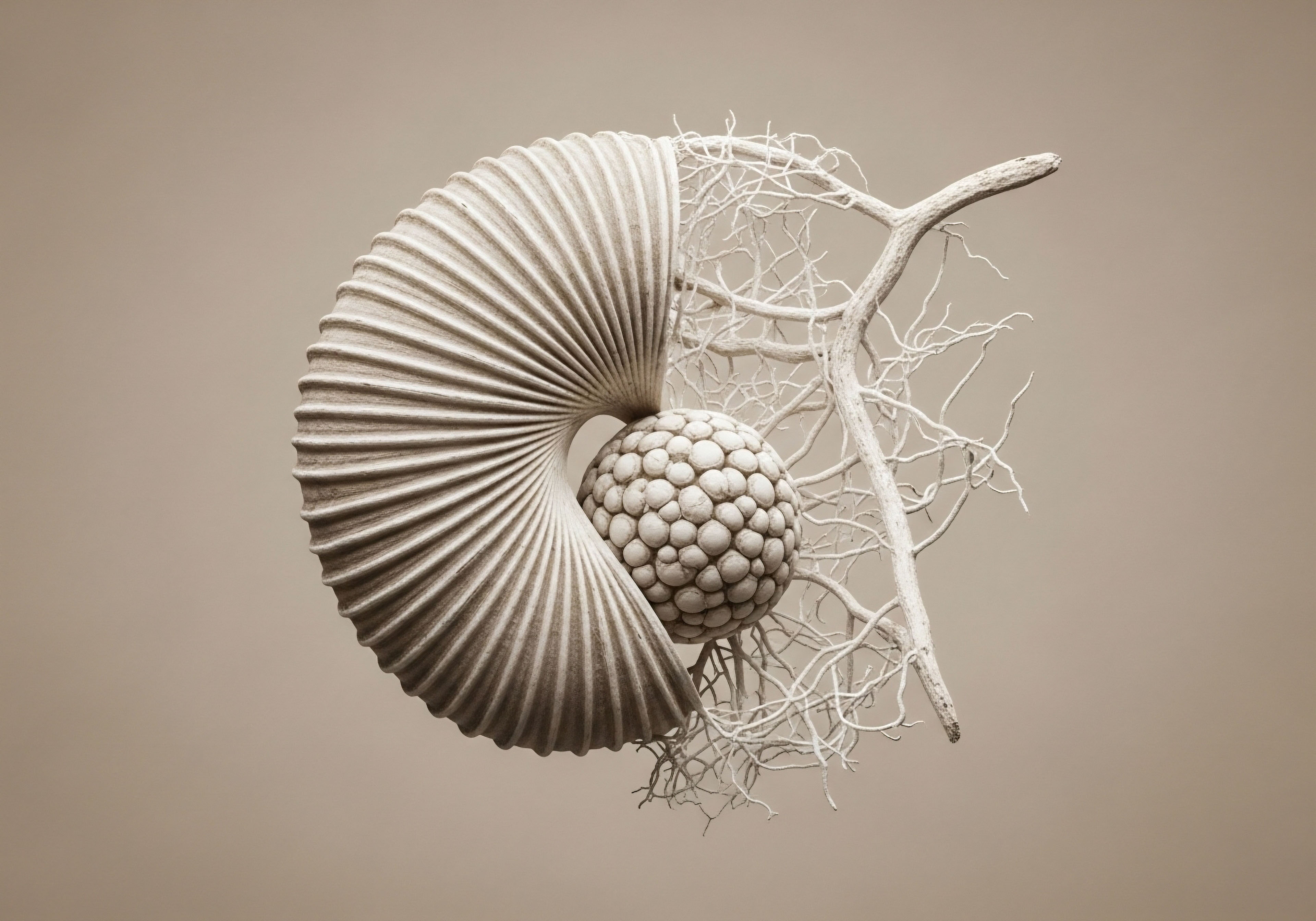

A faltering HPG axis can trigger a cascade of metabolic issues, including insulin resistance and unfavorable changes in body composition.

Cognitive and Mood Disturbances

The brain is rich with receptors for sex hormones. These molecules are not just for reproduction; they are potent neuromodulators that influence cognitive function, mood, and emotional regulation. Incomplete HPG recovery can therefore lead to a range of neurological and psychological symptoms that significantly impact quality of life.

How Hormonal Deficiency Affects the Brain

Testosterone and estrogen support neuronal health, promote the growth of new neural connections (neuroplasticity), and influence the activity of key neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine. When levels are chronically low, individuals often report a collection of symptoms referred to as “brain fog.” This can include difficulty with memory recall, a shortened attention span, and a general feeling of mental slowness.

The decline in dopamine signaling can lead to anhedonia, a loss of pleasure or motivation, while disruptions in serotonin can contribute to anxiety and depressive moods. These are physiological responses to a brain being deprived of the hormones it needs to function optimally.

For men undergoing a post-TRT recovery protocol, a period of low mood or irritability is common as the HPG axis struggles to restart. If this state becomes chronic due to incomplete recovery, it can develop into a persistent depressive disorder.

Similarly, for women in perimenopause experiencing fluctuations and eventual decline in estrogen, mood swings and anxiety are hallmark symptoms of this neuroendocrine transition. Protocols using agents like Gonadorelin or Clomid are designed to restart the brain’s signaling (LH and FSH), which in turn is meant to restore the gonadal hormone production that supports healthy brain function.

Musculoskeletal Decline the Body’s Framework

The structural integrity of the human body depends heavily on hormonal signals. Both bone and muscle are dynamic tissues that are constantly being broken down and rebuilt in a process regulated by sex hormones. A failure of the HPG axis to recover accelerates the decline of this vital framework.

Estrogen is a primary regulator of bone metabolism in both men and women. It slows the activity of osteoclasts, the cells that break down bone tissue. Testosterone contributes to bone density as well, both directly and through its conversion to estrogen within bone tissue.

A chronic deficiency in these hormones leads to a net loss of bone mineral density. Over the long term, this condition, known as osteoporosis, results in bones that are brittle and highly susceptible to fracture. This process is silent and often goes undetected until a fracture occurs.

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is significantly accelerated by low testosterone. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, and its decline not only reduces physical strength and function but also worsens metabolic health by providing fewer places for glucose to be stored.

Peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin, are sometimes used to support musculoskeletal health. These peptides stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone, which works synergistically with sex hormones to promote the maintenance of lean body mass and support tissue repair.

| Symptom Category | Common Manifestations in Men | Common Manifestations in Women |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic |

Increased visceral fat, difficulty losing weight, developing insulin resistance, elevated blood lipids. |

Weight gain (especially abdominal), hot flashes, night sweats, increased risk of metabolic syndrome. |

| Cognitive & Mood |

Low motivation, brain fog, irritability, depression, reduced confidence and drive. |

Mood swings, anxiety, depression, cognitive difficulties, sleep disturbances. |

| Physical |

Loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia), reduced physical stamina, joint pain, decreased bone density. |

Vaginal dryness, skin changes, hair thinning, increased risk of osteoporosis. |

| Sexual Health |

Low libido, erectile dysfunction, reduced testicular size, infertility. |

Low libido, painful intercourse, irregular or absent menstrual cycles, infertility. |

What Are the Cardiovascular Consequences?

The cardiovascular system is also highly responsive to sex hormones. Estrogen has a protective effect on blood vessels, promoting their elasticity and helping to manage cholesterol levels. Testosterone helps maintain a healthy balance of cholesterol and supports cardiac muscle function. Incomplete HPG recovery and the resulting hormonal deficiencies contribute to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease through several mechanisms:

- Lipid Profile Changes ∞ Low levels of sex hormones are associated with an increase in LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and a decrease in HDL (“good”) cholesterol, a condition known as dyslipidemia.

- Endothelial Dysfunction ∞ The inner lining of the blood vessels, the endothelium, loses some of its ability to regulate blood pressure and prevent plaque formation.

- Increased Inflammation ∞ The systemic inflammation driven by metabolic dysfunction also contributes to the development of atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of the arteries.

These factors collectively increase the long-term risk for heart attack and stroke, highlighting that the implications of HPG axis health extend to the body’s most critical systems.

Academic

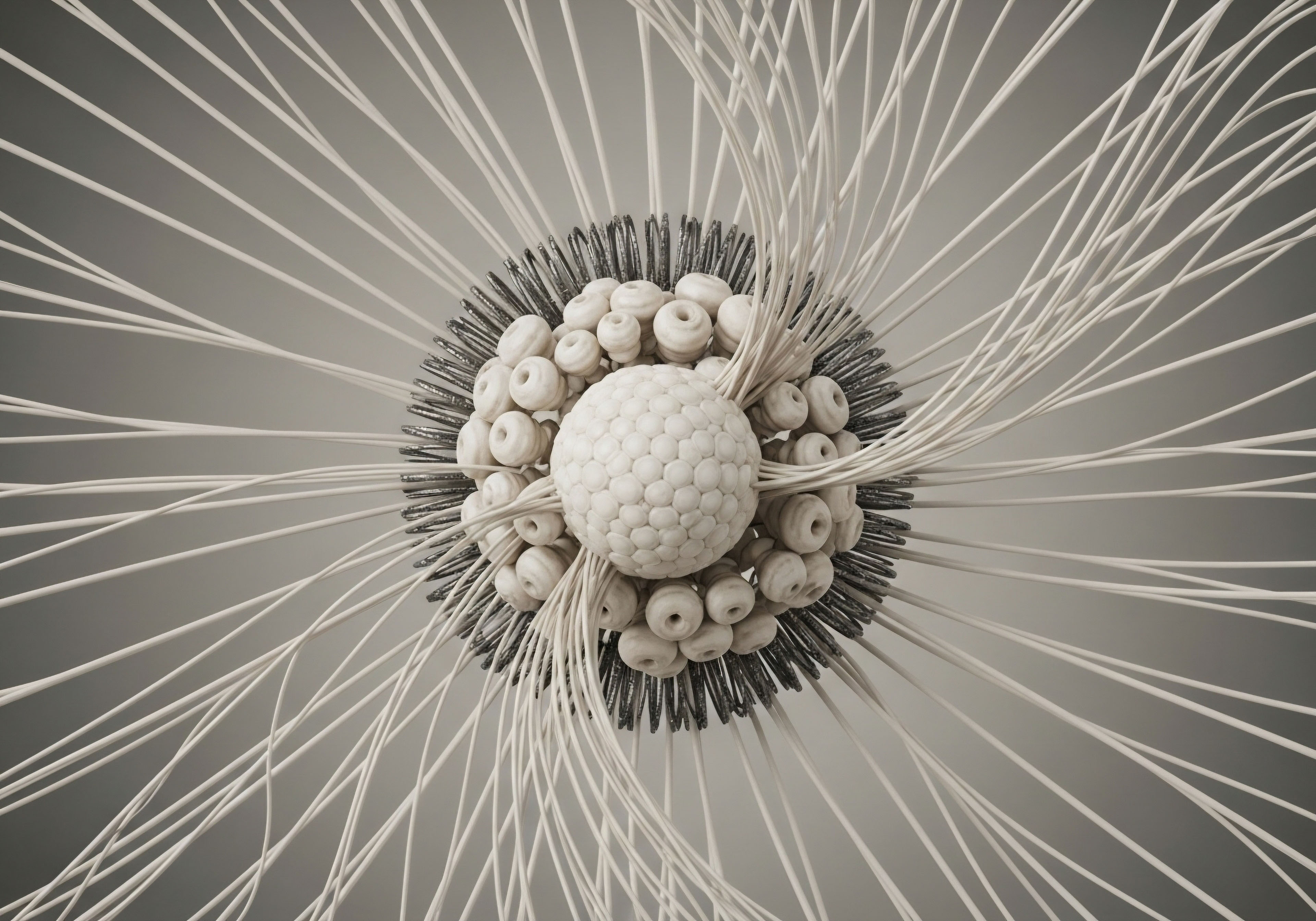

A sophisticated analysis of incomplete Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis recovery moves beyond a simple inventory of symptoms. It requires a deep investigation into the molecular and cellular mechanisms that connect a failure in central hormonal signaling to systemic pathophysiology. The most profound long-term consequence of this state is the cultivation of a chronic, low-grade inflammatory environment.

This systemic inflammation is a common denominator linking metabolic disease, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular decline. Understanding the role of sex steroids as modulators of the immune system provides a unifying theory for the diverse and debilitating effects of persistent hypogonadism.

The Immunomodulatory Role of Sex Hormones

Sex steroid hormones, including testosterone and estradiol, exert powerful effects on both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Their receptors are expressed on a wide variety of immune cells, including T-cells, B-cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

The signaling that results from hormone-receptor binding directly influences gene transcription, altering the production and release of cytokines, the signaling proteins of the immune system. Generally, androgens like testosterone tend to have an immunosuppressive effect, downregulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). Estradiol has a more complex, concentration-dependent role, but it is critical for maintaining immune homeostasis.

In a state of incomplete HPG axis recovery, the loss of these hormonal modulators leads to a dysregulation of the immune response. The system becomes biased toward a pro-inflammatory state. Macrophages and other innate immune cells, freed from the suppressive influence of adequate testosterone levels, become hyper-responsive.

This results in a persistent, elevated baseline of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, creating the very definition of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation. This is a condition that silently damages tissues over time and is a well-established driver of most chronic, age-related diseases.

Persistent hormonal deficiency resulting from incomplete HPG axis recovery can foster a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state throughout the body.

How Does HPG Dysfunction Drive Metabolic Inflammation?

The link between hypogonadism and metabolic disease is bidirectional and self-reinforcing, with inflammation as the central mediator. Visceral adipose tissue, which accumulates in states of low testosterone, is not an inert storage depot. It is a highly active endocrine organ that secretes its own panel of inflammatory cytokines, known as adipokines.

As visceral fat mass increases, it becomes infiltrated with pro-inflammatory macrophages, which further amplify the release of TNF-α and IL-6. These cytokines then act locally and systemically to induce insulin resistance in muscle and liver tissue. This insulin resistance, in turn, promotes further fat storage, creating a vicious cycle of metabolic inflammation.

The failure to restore adequate testosterone levels via a complete HPG axis recovery prevents the body from breaking this cycle. Testosterone directly inhibits the differentiation of adipocyte precursor cells and promotes a healthier, less inflammatory fat distribution pattern. Without it, the inflammatory phenotype of adipose tissue becomes entrenched.

| Biomarker Category | Marker | Typical Derangement in Hypogonadism | Associated Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory | High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) |

Elevated |

Systemic inflammation, increased cardiovascular risk. |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) |

Elevated |

Drives insulin resistance, contributes to joint inflammation. |

|

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) |

Elevated |

Associated with fatigue, depression, and metabolic syndrome. |

|

| Metabolic | Fasting Insulin & Glucose |

Elevated (HOMA-IR score increased) |

Indicates insulin resistance, pre-diabetes. |

| Triglycerides |

Elevated |

Dyslipidemia, increased cardiovascular risk. |

|

| HDL Cholesterol |

Decreased |

Reduced reverse cholesterol transport, higher atherosclerotic risk. |

|

| Hormonal | Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

Often Elevated |

Reduces bioavailable (free) testosterone and estrogen. |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Inappropriately Normal or Low |

Indicates a central (hypothalamic/pituitary) failure to respond to low gonadal hormones. |

Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Decline

The concept of neuroinflammation is central to understanding the cognitive symptoms of incomplete HPG recovery. The brain has its own resident immune cells, known as microglia. In a healthy state, microglia perform housekeeping functions, clearing cellular debris. In the presence of systemic inflammation or the absence of hormonal modulation, microglia can shift to a chronic, pro-inflammatory state.

Activated microglia release inflammatory cytokines directly within the brain tissue, which can impair synaptic function, reduce the production of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), and even contribute to neuronal cell death over the long term. BDNF is critical for learning, memory, and mood.

Its suppression, driven by a combination of low sex hormone levels and high inflammation, provides a clear biological basis for the brain fog, memory issues, and depressive symptoms associated with chronic hypogonadism. The therapeutic goal of protocols that restore hormonal balance is to quell this neuroinflammatory fire, thereby allowing for the restoration of normal cognitive architecture and function.

The Crosstalk with the HPA Axis

No discussion of long-term endocrine dysfunction is complete without examining the interplay with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system. Chronic psychological or physiological stress leads to sustained high levels of cortisol. Cortisol has a direct suppressive effect on the HPG axis at the level of the hypothalamus, inhibiting GnRH release.

Therefore, a state of chronic stress can be both a cause of HPG suppression and a major barrier to its recovery. If the HPA axis remains dysregulated, with either chronically high or erratically patterned cortisol output, it will continuously undermine any attempt by the HPG axis to restart.

This creates a complex clinical picture where symptoms of HPA dysfunction (e.g. fatigue, sleep disruption, anxiety) and HPG dysfunction (e.g. low libido, muscle loss, depression) overlap and amplify one another. A successful recovery strategy must address both axes, often requiring stress modulation techniques and adaptogenic support alongside any direct hormonal or peptide interventions aimed at the HPG axis.

References

- . Problemy Endokrinologii, 66(4), 60 ∞ 68. 2020.

- Alves, F. J. et al. “Nonsteroidal SARMs can significantly suppress endogenous testosterone and require post-cycle strategies to re-establish HPG axis function.” Asian Journal of Andrology.

- Brighten, J. “What is HPA Axis Dysfunction + 7 Steps to Heal HPA-D.” Dr. Jolene Brighten. 2023.

- de Souza, M. J. & Williams, N. I. “Physiological aspects and clinical sequelae of the female athlete triad.” Human reproduction update, 10(5), 427-449. 2004.

- El Osta, B. et al. “Extensive clinical experience ∞ Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovery after adrenalectomy for corticotropin-independent cortisol excess.” Surgery, 167(1), 226-233. 2020.

- George, A. & Rajaratnam, V. “Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Disorders Impacting Female Fertility.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 99(11), 4023-4033. 2014.

- Rachoń, D. “Metformin treatment may mitigate the unfavorable effect of discontinuation of testosterone treatment on hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis activity and sexual function in men with late-onset hypogonadism.” Endocrine, 54(2), 549-551. 2016.

- Sinclair, M. Grossmann, M. & Hoermann, R. “The hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis in the critically ill.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 105(3), dgz242. 2020.

Reflection

The information presented here maps the biological consequences of a system in disarray. It connects symptoms to mechanisms and provides a framework for understanding the body as an integrated whole. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ it transforms abstract feelings of being unwell into a concrete set of physiological challenges that can be addressed.

Your personal health narrative is written in the language of these biological systems. Recognizing the patterns and understanding the signals is the foundational step. The path forward involves a partnership, a data-driven investigation into your unique physiology to create a personalized protocol. The ultimate goal is to move beyond managing symptoms and toward the restoration of the body’s innate capacity for vitality and function.

Glossary

hpg axis

muscle mass

testosterone replacement therapy

post-cycle therapy

gonadorelin

hormonal deficiency

hpg axis recovery

sex hormones

insulin resistance

sarcopenia

clomid

osteoporosis

systemic inflammation

hypogonadism

neuroinflammation