Fundamentals

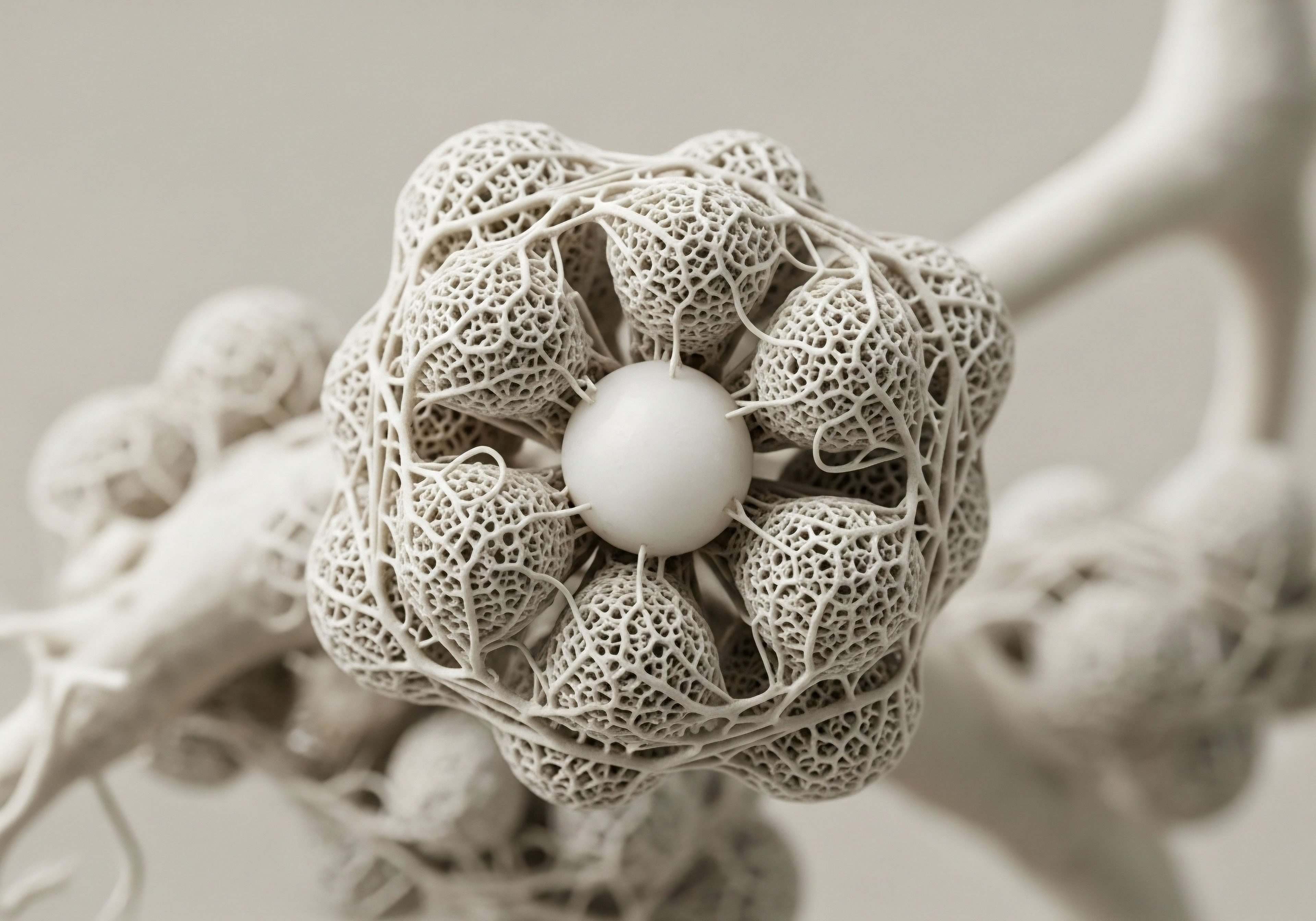

You may feel a sense of apprehension when the conversation turns to hormonal interventions and heart health. This is a valid and understandable response, born from decades of conflicting headlines and fragmented information. Your body’s endocrine network is an intricate communication system, a silent, ceaseless dialogue conducted through chemical messengers called hormones.

Understanding the language of this system is the first step toward demystifying its connection to your cardiovascular vitality. It is a journey into your own biology, a process of learning how to interpret the signals your body is sending so you can participate actively in your own wellness.

The cardiovascular system, with the heart at its center, is a primary recipient of these hormonal messages. Key hormones like testosterone and estrogen are powerful regulators of its function. They influence the flexibility of your blood vessels, the way your body processes cholesterol, and the baseline level of inflammation throughout your system.

When these hormonal signals are balanced and consistent, they contribute to a state of cardiovascular resilience. When they become deficient, excessive, or erratic, the harmony can be disrupted, creating conditions that may affect long-term heart health.

The Core Messengers and Their Cardiovascular Roles

To grasp the long-term implications of hormonal therapies, we must first appreciate the baseline functions of the hormones being supplemented. These molecules are not isolated actors; they are part of a deeply interconnected physiological web.

- Testosterone is often associated with male physiology, yet it is vital for both men and women. It plays a direct role in maintaining the health of the endothelium, the delicate inner lining of your blood vessels. A healthy endothelium produces nitric oxide, a molecule that allows vessels to relax and expand, promoting healthy blood flow and pressure. Testosterone also influences muscle mass, including the heart muscle itself, and impacts the body’s management of lipids.

- Estrogen, similarly crucial for both sexes, has well-documented protective effects on the cardiovascular system. It supports favorable cholesterol profiles by helping to lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or “bad” cholesterol) and raise high-density lipoprotein (HDL, or “good” cholesterol). Its influence on blood vessel dilation complements the action of testosterone, further contributing to vascular health.

- Progesterone works in concert with estrogen, particularly in women. Its primary role in this context is to balance the effects of estrogen, especially on the uterine lining. Its direct cardiovascular effects are more subtle, yet its presence is integral to the overall hormonal symphony.

What Are the Key Cardiovascular Health Markers?

When we discuss cardiovascular health, we are referring to a set of measurable biological signposts. Hormonal interventions can influence these markers, and monitoring them provides a clear picture of the body’s response to therapy. Understanding these markers is essential for any productive conversation about long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

A clear comprehension of your own biological markers transforms abstract health risks into tangible, manageable data points.

These metrics are the data points that allow you and your clinician to track the impact of any wellness protocol. They are the language through which your cardiovascular system communicates its status.

| Marker Category | Specific Measurement | Significance in Cardiovascular Health |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Panel | LDL Cholesterol, HDL Cholesterol, Triglycerides, ApoB | This panel assesses the fats in your bloodstream. High levels of LDL cholesterol, specifically the number of LDL particles (ApoB), can lead to plaque buildup in arteries (atherosclerosis), while HDL cholesterol helps remove excess cholesterol. |

| Inflammatory Markers | High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) | hs-CRP measures a baseline level of inflammation in the body. Chronic inflammation is a known contributor to all stages of atherosclerosis, from plaque formation to rupture. |

| Blood Pressure | Systolic and Diastolic Pressure | This measures the force of blood against your artery walls. Consistently high blood pressure (hypertension) damages blood vessels and forces the heart to work harder, increasing risk. |

| Endothelial Function | Flow-Mediated Dilation (FMD) | This is a direct assessment of blood vessel health. It measures how well arteries dilate in response to increased blood flow, which is a nitric oxide-dependent process. Impaired FMD is one of the earliest detectable signs of cardiovascular disease. |

| Metabolic Markers | Fasting Glucose, Insulin, Hemoglobin A1c | These markers reflect how your body manages blood sugar. Poor glucose control and insulin resistance are strongly linked to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, accelerating cardiovascular disease processes. |

The central question this exploration seeks to answer is how precisely calibrated hormonal support affects these markers over the long term. The clinical data reveals a complex picture, one where the type of hormone used, the delivery method, and the individual’s baseline health create a unique risk-and-benefit profile. The journey forward involves moving past generalized fears and into a space of personalized, data-driven understanding.

Intermediate

Advancing from foundational concepts, the conversation about hormonal interventions and cardiovascular health becomes a matter of specifics. The long-term effects are deeply tied to the precise nature of the protocol, including the type of hormone, the method of administration, and the use of supportive medications.

Each element of a given therapy is chosen to achieve a specific biological effect, and each carries its own set of considerations for cardiovascular wellness. The goal is to restore physiological balance, a process that requires a nuanced understanding of these clinical tools.

Protocols for Male Hormonal Optimization

For men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), a comprehensive protocol involves more than just testosterone. It is a carefully constructed regimen designed to optimize testosterone levels while managing potential downstream effects, particularly the conversion of testosterone to estrogen and the maintenance of the body’s own hormonal signaling pathways.

The Components of a Modern TRT Protocol

A typical, well-managed protocol for men includes several key agents working in concert.

- Testosterone Cypionate This is the primary therapeutic agent, a bioidentical form of testosterone delivered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. Its purpose is to restore testosterone levels to a healthy, youthful range. Large-scale studies like the TRAVERSE trial have provided reassuring data, showing that for men with hypogonadism, TRT did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). A primary physiological marker to monitor is hematocrit, the concentration of red blood cells. Testosterone can stimulate red blood cell production, and while this is often beneficial, excessive elevation can increase blood viscosity, a potential cardiovascular concern that requires clinical oversight.

- Anastrozole This oral medication is an aromatase inhibitor. The aromatase enzyme converts a portion of testosterone into estrogen. In men, some estrogen is essential for bone health, cognitive function, and libido. Excessive estrogen, however, can lead to unwanted side effects. Anastrozole is used judiciously to modulate this conversion and maintain an optimal testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. Its cardiovascular impact requires attention; studies indicate that aromatase inhibitors can lead to less favorable lipid profiles, specifically by increasing LDL cholesterol. This makes lipid monitoring a critical part of the long-term management strategy.

- Gonadorelin This peptide is a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist. It is used in TRT protocols to mimic the natural signals from the hypothalamus, thereby encouraging the pituitary gland to continue sending signals (LH and FSH) to the testes. This helps maintain testicular size and function. The cardiovascular safety of GnRH analogues has been studied extensively, primarily in the context of prostate cancer treatment where they are used to suppress testosterone. Some studies have suggested a link between GnRH agonists and an increased risk of cardiovascular events in that specific population. Its use in TRT is at a much different dosage and for a different purpose, yet it underscores the need for comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment.

Protocols for Female Hormonal Optimization

For women, hormonal therapy is most often considered during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal transitions. The conversation is dominated by the “timing hypothesis,” a concept that has reshaped our understanding of cardiovascular risk.

The cardiovascular effects of hormone therapy in women are critically dependent on when in a woman’s life the therapy is initiated.

Why Does the Timing of Menopausal Hormone Therapy Matter?

Early, large-scale trials like the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studied women who were, on average, many years past menopause. These trials showed an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Subsequent analysis revealed that initiating hormones in a vascular system that already has underlying atherosclerotic plaque may have a destabilizing effect.

Conversely, initiating therapy in younger women (under 60) or those within 10 years of menopause appears to be safe and may even offer cardiovascular protection. This understanding is central to modern clinical practice.

The Critical Difference in Delivery Methods

How a hormone enters the body profoundly changes its effect on cardiovascular markers. This is especially true for estrogen.

| Delivery Method | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Cardiovascular Markers |

|---|---|---|

| Oral Estrogen | After ingestion, the hormone is absorbed and passes through the liver before entering systemic circulation (the “first-pass effect”). | This hepatic first-pass metabolism is known to increase the production of clotting factors and inflammatory markers like C-Reactive Protein (CRP). This elevation in CRP is a key mechanism behind the increased cardiovascular risk associated with oral estrogen. |

| Transdermal Estrogen (Patches, Gels) | The hormone is absorbed directly through the skin into the bloodstream, largely bypassing the liver’s first-pass effect. | This route avoids the significant increase in CRP and clotting factors seen with oral preparations. For this reason, transdermal delivery is generally considered the safer option from a cardiovascular standpoint and is preferred for women with any underlying cardiovascular risk factors. |

In addition to estrogen, protocols for women often include:

- Progesterone For women with a uterus, progesterone (often micronized, bioidentical progesterone) is essential to protect the uterine lining from the growth-promoting effects of estrogen. It has a generally neutral or even slightly beneficial effect on cardiovascular markers, including a mild anti-inflammatory action.

- Low-Dose Testosterone Women also produce and require testosterone for energy, libido, and cognitive clarity. Small, carefully dosed amounts of testosterone can be added to a woman’s protocol, with similar monitoring parameters as men, including lipid profiles and hematocrit.

Peptide Therapies and Cardiovascular Considerations

Growth hormone secretagogues like Ipamorelin and CJC-1295 are peptides that stimulate the pituitary gland to release growth hormone (GH). They are used to improve body composition, recovery, and sleep. While they operate differently from sex hormone therapies, they also have cardiovascular implications.

The FDA has noted that some of these peptides can cause an increased heart rate and vasodilation (widening of blood vessels), which could lead to transient low blood pressure. While research into their long-term effects is ongoing, these potential acute effects warrant caution, particularly in individuals with pre-existing cardiac conditions.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the long-term cardiovascular implications of hormonal interventions requires a shift in perspective. We move from cataloging individual risk factors to examining the integrated, systems-level biology that governs vascular health. The central arena where these hormonal inputs are translated into physiological outcomes is the vascular endothelium, a vast and dynamic organ.

Its functional state, along with the pervasive influence of systemic inflammation, forms the mechanistic bedrock upon which cardiovascular risk is built or dismantled. The specific hormonal protocols we employ are, in essence, inputs into this complex system, with the potential to either preserve endothelial integrity and quell inflammation or to inadvertently disrupt these homeostatic processes.

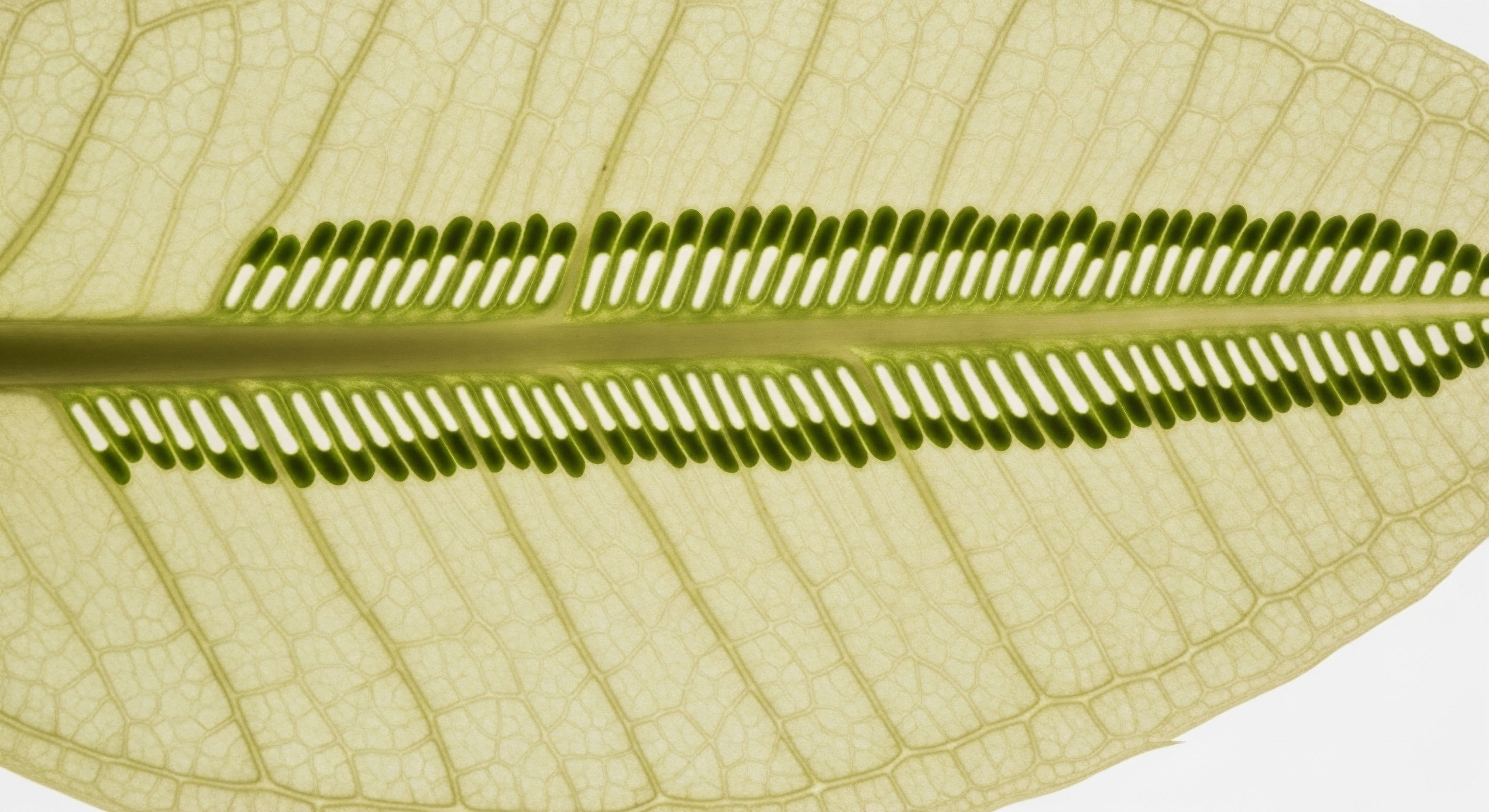

The Endothelium as the Epicenter of Hormonal Action

The endothelium is a single layer of cells lining all blood vessels, acting as a critical interface between the blood and the vessel wall. Its health is paramount for cardiovascular function. Endothelial dysfunction is characterized by a reduced capacity to produce nitric oxide (NO), a key signaling molecule that mediates vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation, and suppresses inflammation. This state is considered a final common pathway for most cardiovascular risk factors and a very early event in the development of atherosclerosis.

How Do Sex Hormones Modulate Endothelial Function?

Sex hormones exert profound and direct effects on endothelial cells, which are equipped with receptors for both androgens and estrogens.

- Testosterone and Nitric Oxide Synthesis Physiologically normal levels of testosterone support endothelial health. Testosterone has been shown to increase the expression and activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for producing NO. This action promotes healthy vasodilation and blood pressure control. Studies demonstrate a clear association between low endogenous testosterone levels and impaired flow-mediated dilation (FMD), a direct measure of endothelial function. The relationship is biphasic; both deficient and supraphysiological levels of androgens can be detrimental, with excessively high doses potentially impairing endothelial function.

- Estrogen’s Vasculoprotective Pathways Estrogen, acting through its receptors on endothelial cells, also potently stimulates eNOS activity. This is a primary mechanism for its vasculoprotective effects. It contributes to vasodilation and has antioxidant properties within the vessel wall, protecting NO from degradation by reactive oxygen species.

The clinical implication is that restoring hormonal balance with bioidentical therapies can, in principle, restore these protective endothelial mechanisms. The use of transdermal estrogen in women, for instance, preserves these direct vascular benefits without the negative hepatic effects. For men on TRT, achieving a stable, physiological level of testosterone can improve the endothelial dysfunction associated with hypogonadism.

Systemic Inflammation a Critical Mediator

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a unifying driver of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The inflammatory marker most studied in this context is high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), a protein produced by the liver in response to inflammatory signals.

Elevated hs-CRP is not just a marker of risk; it is an active participant in the atherosclerotic process, promoting the uptake of LDL cholesterol into the vessel wall.

Why Does the Route of Administration Dictate the Inflammatory Response?

The link between hormonal interventions and CRP is almost entirely dependent on the route of administration, a phenomenon explained by hepatic first-pass metabolism.

When estrogen is taken orally, it is absorbed from the gut and delivered directly to the liver in high concentrations. This stimulates hepatocytes to ramp up the production of various proteins, including CRP and coagulation factors. This is a pharmacological effect of the delivery method.

Multiple studies, including randomized controlled trials, have confirmed that oral estrogen replacement significantly increases plasma CRP levels. Transdermal estrogen, by contrast, is absorbed directly into the systemic circulation, bypassing this first pass through the liver. As a result, it does not cause a clinically significant increase in CRP levels.

This distinction is of profound clinical importance. The elevation of CRP with oral therapy may represent a pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic state that could offset the direct beneficial effects of estrogen on the vasculature. This mechanism is thought to be a primary reason for the adverse outcomes observed in the WHI trial, which exclusively used oral hormones. The choice of a transdermal route effectively uncouples the vasculoprotective benefits of estrogen from the potentially harmful hepatic inflammatory response.

Aromatase Inhibition and Its Metabolic Consequences

In men on TRT, the use of aromatase inhibitors like anastrozole introduces another layer of complexity. While necessary in some cases to control estrogen levels, the reduction of estrogen has metabolic consequences. Estrogen plays a role in regulating lipid metabolism. Clinical data indicates that the use of anastrozole can lead to an increase in LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol.

From a systems perspective, this intervention, designed to optimize one hormonal ratio, can perturb another critical system ∞ lipid metabolism ∞ which has direct, long-term implications for atherosclerotic plaque development. This necessitates a holistic monitoring approach that tracks not just hormone levels but also the full spectrum of cardiovascular risk markers, including advanced lipid panels that measure LDL particle number (ApoB).

Ultimately, a sophisticated understanding of hormonal therapy’s long-term cardiovascular impact requires viewing the body as a network of interconnected systems. The goal of any intervention is to restore beneficial signaling within this network without causing unintended disruptions elsewhere. This is achieved through personalized protocols that favor delivery methods with better safety profiles (e.g. transdermal over oral estrogen), judicious use of ancillary medications based on comprehensive biomarker analysis, and a continuous process of monitoring and adjustment.

References

- Rossouw, J. E. et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women ∞ principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, vol. 288, no. 3, 2002, pp. 321-33.

- Ridker, P. M. et al. “Hormone replacement therapy and increased plasma concentration of C-reactive protein.” Circulation, vol. 100, no. 7, 1999, pp. 713-16.

- Leder, B. Z. et al. “Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 89, no. 3, 2004, pp. 1174-80.

- Vongpatanasin, W. et al. “Differential effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on C-reactive protein in postmenopausal women.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 41, no. 8, 2003, pp. 1358-63.

- Lincoff, A. M. et al. “Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 389, no. 2, 2023, pp. 107-117.

- Akishita, M. et al. “Low testosterone level is an independent determinant of endothelial dysfunction in men.” Hypertension Research, vol. 30, no. 11, 2007, pp. 1029-34.

- Corona, G. et al. “Testosterone replacement therapy and cardiovascular risk ∞ a review.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 41, no. 2, 2018, pp. 155-171.

- Levine, G. N. et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism and High Cardiovascular Risk ∞ A Review.” JAMA Cardiology, vol. 7, no. 3, 2022, pp. 336-343.

- Boardman, H. M. et al. “Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 3, 2015, CD002229.

- Te-Fu, Chan, et al. “Androgen actions on endothelium functions and cardiovascular diseases.” Journal of Biomedical Science, vol. 17, no. 1, 2010, p. 78.

Reflection

You have now traveled through the complex biological landscape that connects your hormonal state to your cardiovascular future. The information presented here is a map, detailing the known pathways, the established landmarks from clinical trials, and the areas where the terrain is still being charted.

This map is a powerful tool, designed to equip you for a more meaningful and precise conversation about your own health. Your unique physiology, your personal history, and your future goals are the coordinates that will determine your specific path.

The true purpose of this knowledge is to empower you to ask more pointed questions, to understand the ‘why’ behind a protocol, and to become an active, informed partner in the stewardship of your own vitality. The journey to optimized health is a continuous one, built on the foundation of understanding your own intricate and remarkable biology.

Glossary

hormonal interventions

nitric oxide

cardiovascular health

testosterone replacement therapy

testosterone levels

aromatase inhibitor

ldl cholesterol

cardiovascular risk

gonadorelin

blood pressure

endothelial dysfunction

atherosclerosis

endothelial function

transdermal estrogen

cardiovascular disease

c-reactive protein