Fundamentals

Have you noticed a subtle shift in your mental clarity, a fleeting memory, or perhaps a persistent sense of mental fogginess that wasn’t present before? Many individuals, particularly as they approach midlife, report these very real changes in their cognitive abilities.

This experience is not merely a sign of aging; it often signals deeper alterations within the body’s intricate hormonal messaging system. The sensations of struggling to recall a name, losing a thought mid-sentence, or feeling less sharp than usual can be disorienting. Validating these experiences marks the initial step toward reclaiming cognitive vitality.

The long-term influence of estrogen regulation on brain function represents a significant area of scientific inquiry. Estrogen, often primarily associated with reproductive processes, exerts widespread effects throughout the body, including profound actions within the central nervous system. Its presence impacts brain regions vital for higher cognitive functions, such as the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. These areas are instrumental in processes like memory formation, executive function, and spatial awareness.

Cognitive shifts, such as mental fogginess or memory lapses, frequently indicate underlying changes in the body’s hormonal balance.

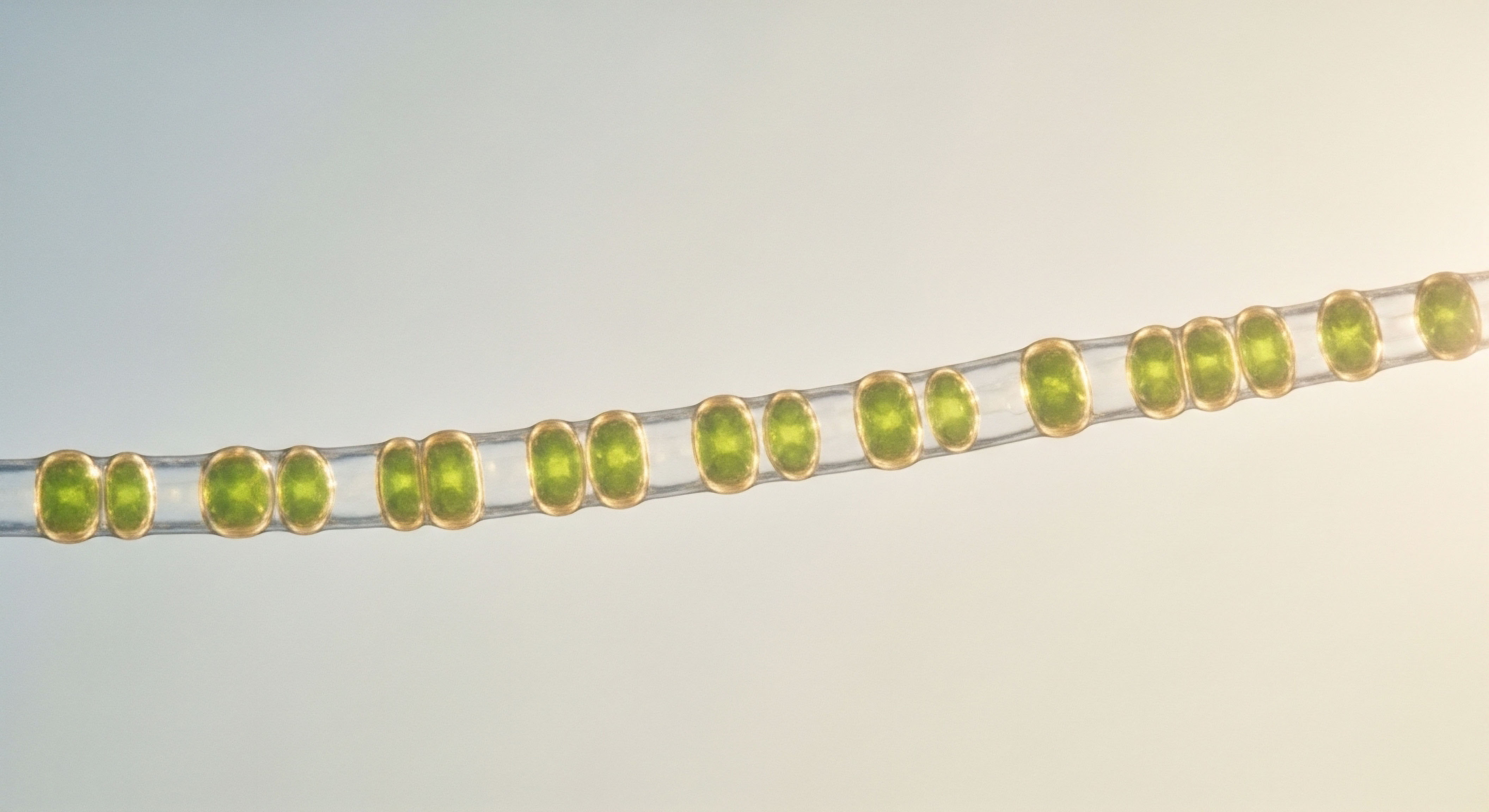

Estrogen’s actions in the brain are complex, mediated by various types of estrogen receptors (ERs). These include estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), and the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1). These receptors are distributed throughout brain cells, including synapses, the communication points between neurons. Activation of these receptors initiates a cascade of signal transduction pathways, leading to both rapid, non-genomic effects and slower, genomic effects that influence gene expression.

The decline in estrogen levels, particularly during the menopausal transition, can significantly affect brain health. Women frequently report difficulties with memory and concentration during this period. Research indicates that the loss of ovarian function, whether natural or surgically induced, can intensify the effects of aging on cognitive abilities. This hormonal shift creates a unique physiological landscape within the brain, altering its responsiveness and resilience.

How Estrogen Shapes Brain Function

Estrogen contributes to brain health through several mechanisms. It promotes spinogenesis and synaptogenesis, the formation of new dendritic spines and synapses, which are essential for neuronal communication and plasticity. This structural remodeling supports the brain’s capacity for learning and memory. Estrogen also influences the production and activity of various neurotransmitters, the chemical messengers that transmit signals between nerve cells.

Beyond its direct effects on neurons, estrogen also influences other brain components, including glial cells and the vasculature. Glial cells, such as astrocytes and microglia, play supportive roles in neuronal function, modulating inflammation and providing metabolic support. Estrogen’s actions on these cells contribute to overall brain resilience and protection against injury. The hormone also impacts cerebral blood flow, ensuring adequate nutrient and oxygen supply to brain tissues, which is vital for sustained cognitive performance.

Understanding Hormonal Fluctuations

The endocrine system operates as a finely tuned network, with hormones acting as messengers that regulate nearly every bodily process. When the balance of these messengers shifts, particularly with a decline in estrogen, the effects can ripple across multiple systems, including cognitive function. This interconnectedness means that symptoms like mental fogginess are not isolated events but rather manifestations of systemic changes. Recognizing this broader context is vital for addressing cognitive concerns effectively.

The experience of hormonal change is deeply personal, yet the underlying biological principles are universal. By understanding how estrogen influences brain architecture and function, individuals can begin to connect their lived experiences with the scientific explanations. This foundational knowledge serves as a compass, guiding personal health choices and discussions with healthcare providers.

Intermediate

Addressing the long-term implications of estrogen regulation on cognitive function requires a precise, clinically informed approach. Personalized wellness protocols aim to recalibrate the body’s biochemical systems, moving beyond symptomatic relief to address underlying hormonal imbalances. These protocols often involve targeted hormonal optimization, carefully tailored to individual physiological needs. The goal is to restore a state of internal equilibrium that supports sustained cognitive vitality.

Hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for both men and women, and the judicious use of progesterone, are designed to influence the endocrine system’s complex feedback loops. These interventions are not about simply replacing a missing hormone; they involve a sophisticated understanding of how various biochemical agents interact within the body’s communication network.

Testosterone Optimization and Cognitive Support

While estrogen’s role in female cognitive health is widely discussed, the contribution of testosterone in women often receives less attention. Testosterone, an androgen, also plays a significant role in brain function, influencing memory, attention, and spatial abilities. Optimal levels of this hormone can enhance cognitive performance, while imbalances can contribute to mental fatigue and difficulties with concentration.

For women experiencing symptoms related to declining testosterone, such as irregular cycles, mood changes, or low libido, specific protocols can be considered. A common approach involves weekly subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate, typically in low doses (0.1 ∞ 0.2ml). This method allows for precise dosage adjustments and consistent delivery.

In some cases, long-acting testosterone pellets may be an option, providing sustained release over several months. When appropriate, an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole might be included to manage potential conversion of testosterone to estrogen, ensuring a balanced hormonal environment.

Testosterone optimization in women can improve cognitive function, mood stability, and overall vitality.

The interplay between testosterone and estrogen is particularly relevant for cognitive health. Testosterone can be aromatized into estrogen within the brain, contributing to the local estrogenic environment. This conversion highlights the interconnectedness of sex steroid pathways and their collective impact on neuronal function. Maintaining appropriate levels of both hormones is paramount for supporting brain resilience.

Progesterone’s Role in Brain Health

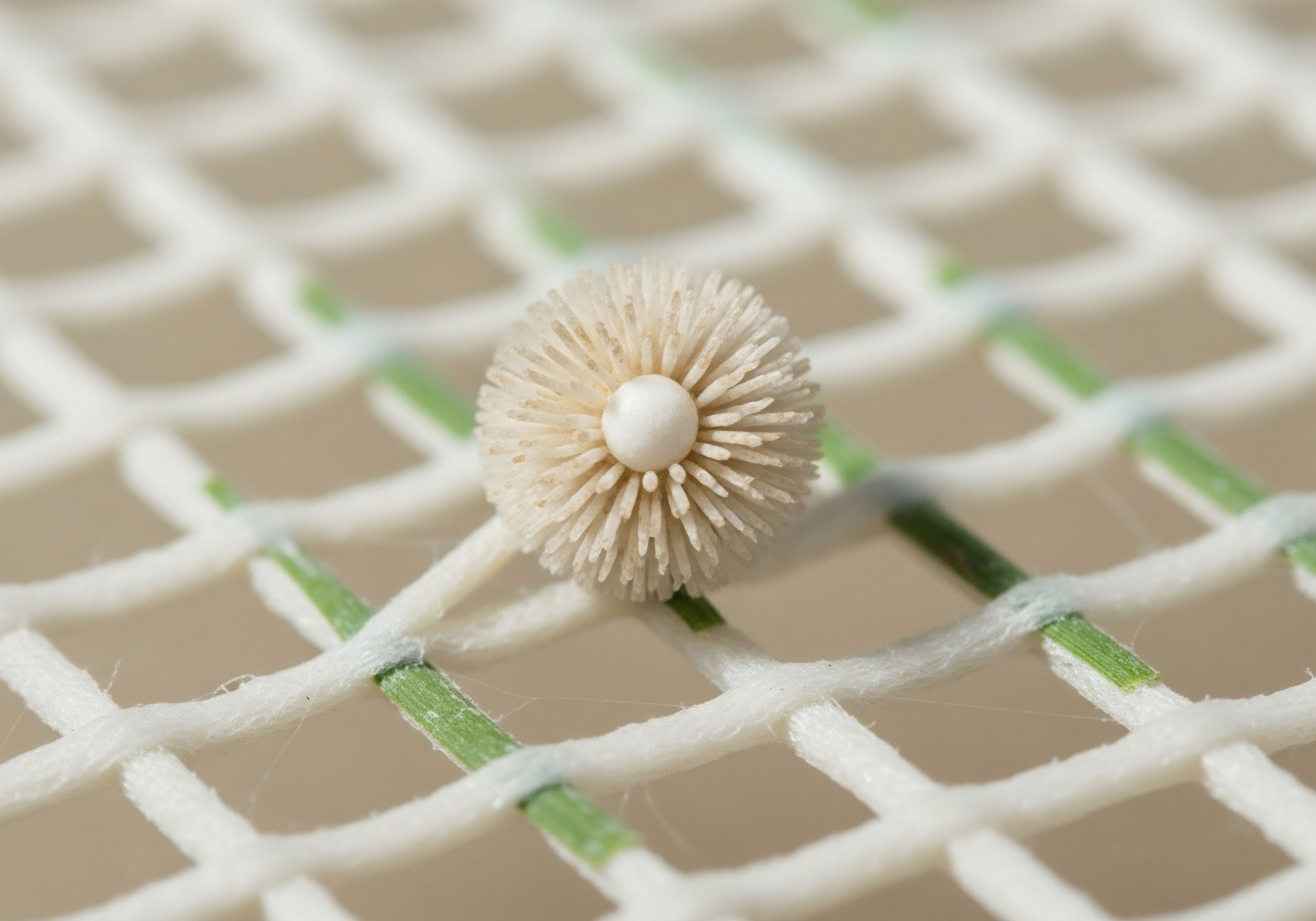

Progesterone, often associated with reproductive health, also exerts significant neuroprotective effects. It is considered a neurosteroid, produced not only by the ovaries but also within the brain itself, by neurons and glial cells. This hormone contributes to neurogenesis, the formation of new brain cells, and supports the repair of damaged neural tissue. It also influences mood regulation and inflammation within the central nervous system.

Clinical protocols for women often include progesterone, with its use determined by menopausal status. For pre-menopausal and peri-menopausal women, progesterone may be prescribed to support cycle regularity and mitigate symptoms. In post-menopausal women, it is frequently co-administered with estrogen to protect the uterine lining and offer additional neurocognitive benefits.

The distinction between natural progesterone and synthetic progestins is important. Research indicates that natural progesterone may offer more favorable neuroprotective effects compared to some synthetic progestins, which have shown mixed results in cognitive studies. This difference underscores the importance of selecting specific formulations in hormonal optimization protocols.

Consider the following comparison of hormonal agents and their cognitive effects:

| Hormonal Agent | Primary Cognitive Influence | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen (Estradiol) | Verbal memory, executive function, neuroprotection | Direct receptor binding (ERα, ERβ, GPER1), synaptogenesis, neurotrophin regulation |

| Testosterone | Spatial abilities, attention, motivation, verbal learning | Androgen receptor activation, aromatization to estrogen, interaction with stress hormones |

| Progesterone | Neuroprotection, memory preservation, mood stability | Neurosteroid action, GABAA receptor modulation, anti-inflammatory effects |

Growth Hormone Peptides and Cognitive Enhancement

Beyond traditional hormonal therapies, certain growth hormone-releasing peptides are gaining recognition for their potential to support cognitive function and overall well-being. These peptides stimulate the body’s natural production of growth hormone, which declines with age. Growth hormone plays a role in cellular repair, metabolic regulation, and brain health.

Peptides such as Sermorelin, Ipamorelin / CJC-1295, and Tesamorelin are utilized to promote anti-aging effects, muscle gain, fat loss, and improved sleep quality. These benefits indirectly support cognitive function by enhancing systemic health and reducing inflammation. A well-rested body with optimized metabolic function is better equipped to maintain mental acuity. While direct cognitive effects are still under investigation, the systemic improvements contribute to a more favorable environment for brain health.

Other targeted peptides, like PT-141 for sexual health and Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) for tissue repair and inflammation, also contribute to overall vitality. By addressing specific physiological needs, these peptides support a comprehensive approach to wellness, which in turn can positively influence cognitive resilience.

Navigating the Timing of Intervention

The timing of hormonal intervention, particularly with estrogen, appears to significantly influence cognitive outcomes. Clinical studies suggest a “critical window” for initiating estrogen therapy, typically near the onset of menopause. Beginning therapy during this period may yield more favorable cognitive benefits, especially concerning verbal memory. Conversely, initiating estrogen therapy much later in life, particularly after age 60, has shown less consistent benefits and, in some cases, potential risks.

This concept underscores the importance of early assessment and personalized planning. Understanding an individual’s unique hormonal trajectory and symptom presentation allows for a more strategic application of therapies, aiming to support brain health proactively rather than reactively.

Academic

The long-term implications of estrogen regulation on cognitive function extend into the intricate molecular and cellular architecture of the brain. Understanding these deep endocrinological connections requires a systems-biology perspective, recognizing that hormonal signals do not operate in isolation but rather within a complex network of biological axes and metabolic pathways. The brain, a highly metabolically active organ, is exquisitely sensitive to fluctuations in steroid hormones, which influence neuronal plasticity, neurotransmission, and cellular survival.

Estrogen’s influence on cognition is mediated through its interaction with specific receptors distributed across critical brain regions. The hippocampus, a structure central to learning and memory, and the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions, possess a high density of estrogen receptors.

These receptors, primarily ERα and ERβ, act as transcription factors, regulating the expression of genes involved in neuronal growth, synaptic function, and neuroprotection. Beyond these genomic actions, estrogen also exerts rapid, non-genomic effects by activating membrane-bound receptors and initiating intracellular signaling cascades, such as the ERK/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways. These rapid responses can modulate synaptic strength and neuronal excitability within milliseconds.

Estrogen influences brain function through both genomic and rapid non-genomic mechanisms, impacting neuronal growth and synaptic communication.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Cognitive Health

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis represents a central regulatory system for sex steroid production, and its integrity is inextricably linked to cognitive well-being. This axis involves a hierarchical communication loop ∞ the hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins, in turn, act on the gonads (ovaries in women, testes in men) to produce sex steroids like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone.

Dysregulation within the HPG axis, often associated with aging and conditions like menopause, can lead to altered sex steroid levels that directly affect brain function. For instance, the age-related decline in ovarian estrogen production during menopause significantly impacts hippocampal-dependent functions, including declarative and spatial memories. The brain’s sensitivity to these changes underscores the HPG axis’s profound influence on cognitive trajectory throughout life.

Consider the intricate feedback mechanisms within the HPG axis:

- Hypothalamus ∞ Produces GnRH, initiating the cascade.

- Pituitary Gland ∞ Responds to GnRH by releasing LH and FSH.

- Gonads (Ovaries/Testes) ∞ Produce sex steroids (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) in response to LH and FSH.

- Negative Feedback ∞ Sex steroids then signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary, modulating GnRH, LH, and FSH release, maintaining hormonal balance.

Neurotransmitter Systems and Estrogen Modulation

Estrogen’s cognitive effects are also mediated through its modulation of various neurotransmitter systems. It influences the activity of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter critical for memory and learning, particularly in the basal forebrain cholinergic system. Estrogen can enhance cholinergic transmission, which may explain some of its beneficial effects on verbal memory.

The hormone also interacts with serotonin and noradrenalin systems, which are involved in mood, attention, and executive function. Alterations in these systems can contribute to cognitive symptoms often reported during periods of hormonal flux. Estrogen’s ability to influence receptor density and signaling pathways for these neurotransmitters highlights its widespread impact on brain chemistry.

Furthermore, estrogen can modulate glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. While glutamate is essential for synaptic plasticity, excessive activation can lead to excitotoxicity, a process implicated in neurodegenerative conditions. Estrogen exhibits neuroprotective properties by regulating glutamate receptor function and reducing oxidative stress, thereby safeguarding neuronal integrity.

Cellular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection

The neuroprotective actions of estrogen are multifaceted, involving both direct effects on neurons and indirect effects mediated by glial cells. Estrogen can attenuate neural injury through mechanisms that involve its receptors, as well as through receptor-independent pathways. For instance, estrogen has been shown to increase the expression of anti-apoptotic genes like bcl-2, promoting cell survival in the face of ischemic or excitotoxic insults.

Another significant mechanism involves estrogen’s role as an antioxidant. It can reduce the production of free radicals and mitigate oxidative damage, a key contributor to neuronal aging and neurodegeneration. This antioxidant capacity helps preserve cellular components and maintain mitochondrial function, which is vital for neuronal energy production.

The interaction of estrogen with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is also a significant area of research. BDNF is a protein that supports the survival of existing neurons and promotes the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses. Estrogen can upregulate BDNF expression, thereby enhancing neuronal plasticity and resilience. This neurotrophic support is a cornerstone of estrogen’s long-term benefits for cognitive function.

The complexity of estrogen’s actions in the brain means that the long-term implications of its modulation are not uniform. Factors such as the timing of intervention, the specific estrogen formulation used, and individual genetic predispositions (e.g. APOE-ε4 status) can all influence cognitive outcomes. This variability underscores the need for highly individualized and data-driven approaches to hormonal optimization, ensuring that interventions align with an individual’s unique biological blueprint and health goals.

The table below summarizes key molecular targets and their cognitive associations:

| Molecular Target | Primary Role | Cognitive Association |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen Receptors (ERα, ERβ, GPER1) | Signal transduction, gene regulation | Synaptic plasticity, memory consolidation |

| Acetylcholine System | Neurotransmission | Learning, memory recall |

| BDNF | Neuronal growth factor | Neurogenesis, synaptic strength, cognitive resilience |

| Glial Cells (Astrocytes, Microglia) | Support, inflammation modulation | Brain environment, neuroprotection |

Considering the Broader Metabolic Context

Cognitive function is not solely dependent on sex hormones; it is deeply intertwined with overall metabolic health. Hormones like estrogen influence glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in the brain. Dysregulation in these metabolic pathways can contribute to cognitive decline. A systems-biology perspective recognizes that optimizing hormonal balance must occur within the context of supporting robust metabolic function, addressing factors such as insulin resistance and inflammation.

The interaction between sex steroids and metabolic hormones, such as insulin and thyroid hormones, creates a complex regulatory network. Estrogen, for example, can influence glucose uptake and utilization in brain regions critical for cognition. When this metabolic efficiency is compromised, neuronal function can suffer, contributing to symptoms like brain fog. Therefore, any long-term strategy for cognitive health must consider the metabolic underpinnings of brain vitality.

References

- Brann, Darrell W. et al. “Neurotrophic and Neuroprotective Actions of Estrogen ∞ Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications.” Vitamins and Hormones, vol. 71, 2005, pp. 123-145.

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Testosterone Could Combat Dementia in Women.” Monash University News, 2013.

- Henderson, Victor W. “Estrogen, Cognition, and Alzheimer’s Disease.” Neurology, vol. 63, no. 5, 2004, pp. 777-780.

- Leblanc, Elizabeth S. et al. “Hormone Replacement Therapy and Cognition ∞ Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” JAMA, vol. 285, no. 11, 2001, pp. 1489-1499.

- McEwen, Bruce S. and Robert J. Milner. “Minireview ∞ Neuroprotective Effects of Estrogen ∞ New Insights into Mechanisms of Action.” Endocrinology, vol. 147, no. 6, 2006, pp. 2623-2629.

- Mendez, Mario F. and Jorge R. Barrio. “The Effect of Hormone Replacement Therapy on Cognitive Function in Female Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease ∞ A Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, vol. 35, 2020, pp. 1533317520938585.

- Petersen, S. L. et al. “Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, vol. 56, 2020, pp. 100812.

- Rocca, Walter A. et al. “Long-term consequences of estrogens administered in midlife on female cognitive aging.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, vol. 33, no. 2, 2012, pp. 166-175.

- Schumacher, Michael, et al. “Progesterone and Neuroprotection.” Hormones and Behavior, vol. 63, no. 2, 2013, pp. 277-282.

- Shumaker, Sally A. et al. “Estrogen Plus Progestin and the Incidence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Postmenopausal Women ∞ The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study ∞ A Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA, vol. 291, no. 24, 2004, pp. 2947-2958.

- Snyder, Peter J. et al. “Effects of Testosterone Administration on Cognitive Function in Hysterectomized Women with Low Testosterone Levels ∞ A Dose ∞ Response Randomized Trial.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 2, 2016, pp. 582-590.

- Wise, Phyllis M. et al. “Hypothalamic ∞ Pituitary ∞ Gonadal Axis Involvement in Learning and Memory and Alzheimer’s Disease ∞ More than “Just” Estrogen.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, vol. 36, 2015, pp. 11-23.

Reflection

As you consider the intricate connections between estrogen regulation and cognitive function, reflect on your own experiences. Have you recognized patterns in your mental acuity that align with hormonal shifts? The scientific explanations presented here are not merely abstract concepts; they are reflections of the biological processes occurring within your own body. This knowledge serves as a powerful tool, allowing you to move beyond simply observing symptoms to understanding their origins.

Your personal health journey is unique, and the path to reclaiming vitality is similarly individualized. This information provides a foundation, a starting point for deeper conversations with your healthcare provider. It encourages a proactive stance, where you become an informed participant in optimizing your well-being. The goal is to calibrate your biological systems, not just to alleviate discomfort, but to truly restore your inherent capacity for mental sharpness and sustained function.

What Steps Can You Take Next?

Consider documenting your cognitive experiences and any associated hormonal symptoms. This personal data can be invaluable in guiding clinical discussions. A thorough assessment of your hormonal status, including a comprehensive lab panel, can provide objective insights into your unique biochemical landscape. Armed with this understanding, you can collaboratively develop a personalized strategy that aligns with your specific needs and aspirations for long-term cognitive health.