Fundamentals

A lab report indicating elevated liver enzymes can be a source of significant concern. You might feel a sense of unease, wondering what this clinical data point signifies about your internal health. This response from your body is a valid and important signal. It is a direct communication from your biological systems, asking for closer attention.

Seeing those numbers on a page represents a tangible link to the complex processes occurring within you, and understanding their meaning is the first step toward proactive stewardship of your well-being.

Your liver is a vast and intricate biochemical processing plant, central to your body’s ability to function, repair, and thrive. It performs hundreds of critical tasks, from metabolizing nutrients and clearing toxins to producing essential proteins. The enzymes in question, such as Alanine Transaminase (ALT) and Aspartate Transaminase (AST), are proteins that facilitate chemical reactions inside liver cells, or hepatocytes.

When these cells experience stress or damage, their membranes can become compromised, allowing these enzymes to leak into the bloodstream. Therefore, elevated enzyme levels in a blood test serve as a sensitive marker of hepatic stress. This is a direct indicator that a higher-than-normal number of liver cells are experiencing some form of injury.

The Liver as a Metabolic Hub

Your liver’s health is inextricably linked to your overall metabolic state. It is a primary regulator of blood sugar, cholesterol, and triglycerides. One of the most prevalent reasons for sustained liver enzyme elevation in modern society is a condition known as Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), previously called Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD).

This condition arises when the liver begins to accumulate excess fat within its cells. This fat accumulation is not a passive event; it initiates a low-grade inflammatory response that can stress and damage hepatocytes, leading to the release of enzymes.

The development of MASLD is deeply connected to the body’s endocrine system, particularly the hormone insulin. Insulin’s job is to signal cells to take up glucose from the blood for energy. When cells, especially in the muscles and fat tissue, become less responsive to this signal, a state of insulin resistance develops.

To compensate, the pancreas produces more insulin. This environment of high insulin levels signals the liver to accelerate fat production, contributing directly to the fatty infiltration that characterizes MASLD and places stress on the organ.

Elevated liver enzymes are a direct biological signal of liver cell stress, often linked to underlying metabolic and hormonal imbalances.

What Are the Initial Systemic Consequences?

When liver function is compromised, the effects extend far beyond the liver itself. Because the liver is a central player in hormonal regulation and detoxification, even mild, chronic elevations in its enzymes can point to broader systemic issues. The body operates as an integrated system, and a disturbance in a central hub like the liver will inevitably create ripple effects. These can manifest as feelings of fatigue, difficulty managing weight, or changes in digestive health.

Understanding this connection is empowering. The information from your lab work provides a starting point for a deeper inquiry into your health. It moves the conversation from a simple number to a systemic perspective, viewing the liver as a reflection of your overall metabolic and endocrine well-being. Addressing the root causes of liver stress often involves a comprehensive look at diet, physical activity, and the balance of the entire hormonal network, which forms the foundation of long-term vitality.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial signal of elevated liver enzymes requires a deeper look into the intricate communication network that governs your physiology. Your body functions through a series of sophisticated feedback loops, and the liver is a critical node in this network.

When its function is altered, it disrupts the balance of the endocrine system, the body’s internal messaging service. This disruption is not a one-way street; hormonal imbalances in turn place further strain on the liver, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that can impact long-term health.

The Central Role of Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis

Insulin resistance is a primary driver in this dysfunctional cycle. In a balanced state, insulin effectively manages blood glucose. With insulin resistance, the body’s cells are deafened to insulin’s signal. The pancreas compensates by secreting higher levels of insulin, leading to hyperinsulinemia. This state has profound effects on the liver.

The persistently high insulin levels instruct the liver to ramp up de novo lipogenesis, the process of creating new fat molecules (triglycerides) from carbohydrates. These fats accumulate in hepatocytes, causing hepatic steatosis (a fatty liver).

This fatty infiltration makes the liver itself more insulin resistant. A selective form of hepatic insulin resistance develops, where the liver ignores insulin’s signal to stop producing glucose, yet it continues to obey the signal to produce fat. This dual dysfunction results in both high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) and high levels of circulating triglycerides, further promoting metabolic disruption.

The physical presence of excess fat droplets within the liver cells also induces cellular stress and inflammation, causing the release of enzymes like ALT and GGT, which are considered direct biomarkers of this condition.

The cycle of insulin resistance and fat accumulation in the liver creates a state of selective hepatic dysfunction, disrupting both glucose and lipid metabolism.

How Does Liver Health Affect Sex Hormones?

The liver’s health is intimately tied to the regulation of sex hormones in both men and women. The liver produces sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), a protein that binds to hormones like testosterone and estrogen, transporting them through the bloodstream and regulating their availability to tissues. A stressed, fatty liver produces less SHBG. Lower SHBG levels mean that more sex hormones are in their “free” or unbound state, which can disrupt the delicate hormonal balance.

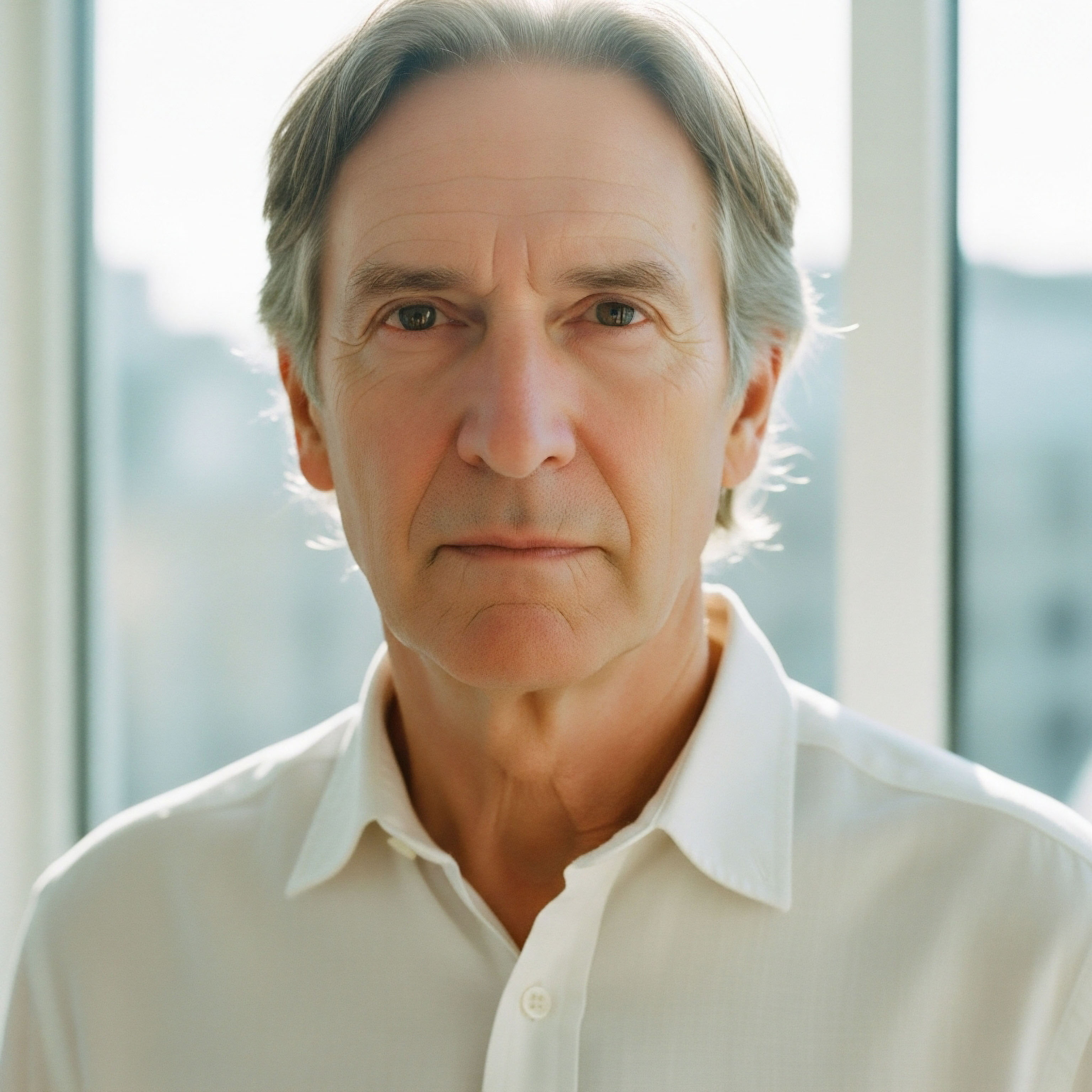

The Male Endocrine Axis

In men, low testosterone is strongly associated with the presence and severity of MASLD. This relationship is bidirectional. Low testosterone can contribute to the accumulation of visceral fat and worsen insulin resistance, both of which drive fat deposition in the liver.

Conversely, a compromised liver, burdened by fat and inflammation, can impair the body’s ability to produce and regulate testosterone effectively. The inflammatory signals originating from the liver can suppress the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, the hormonal cascade that stimulates testosterone production.

This creates a challenging cycle where low testosterone worsens liver health, and poor liver health further suppresses testosterone. The testosterone-to-estradiol (T/E2) ratio is a key indicator; a lower ratio, often seen in men with MASLD, points to an imbalance that favors inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

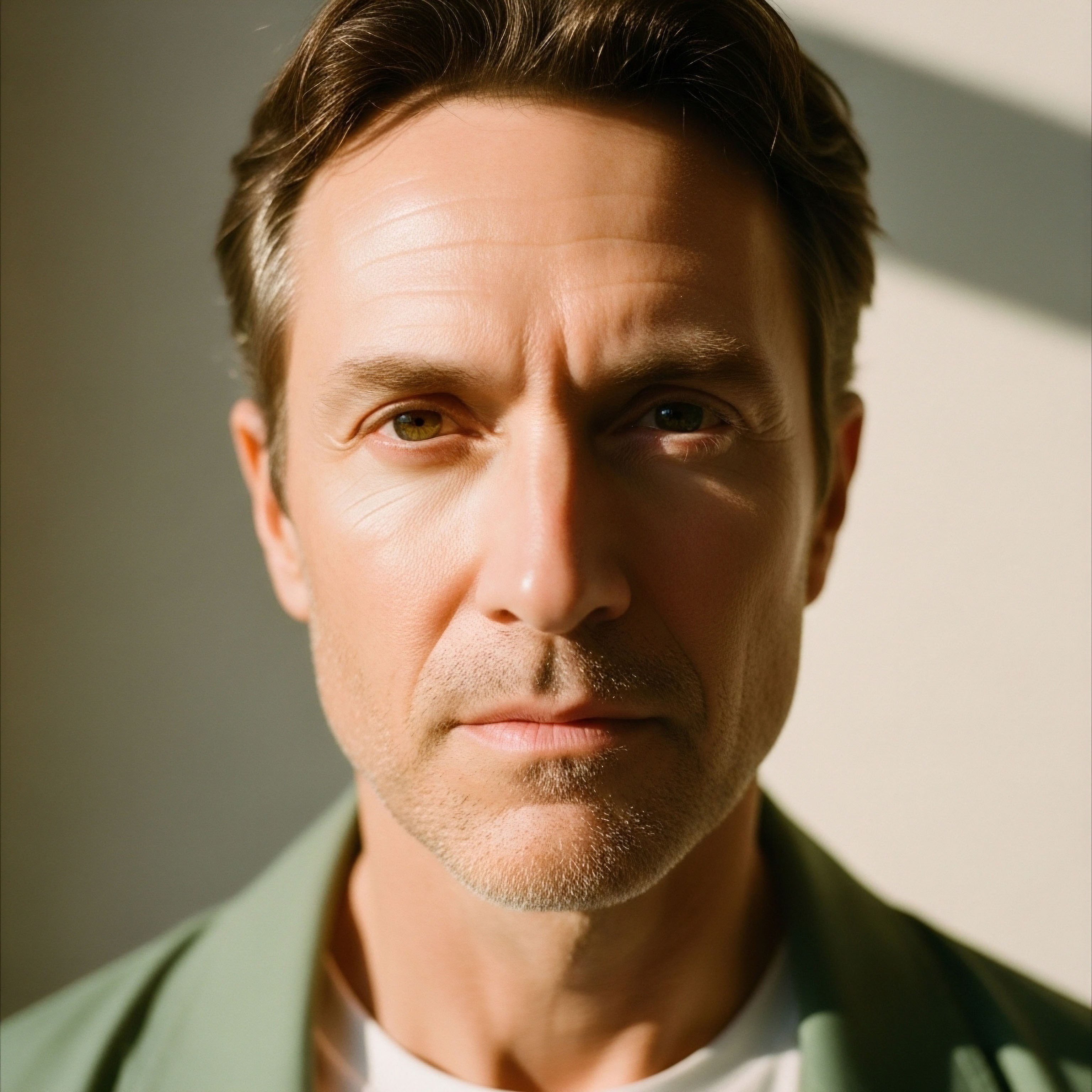

The Female Endocrine Axis

In women, the hormonal picture is different but equally connected to liver function. In pre-menopausal women, conditions characterized by high levels of androgens (male hormones), such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), show a very high prevalence of MASLD.

This hyperandrogenic state, coupled with the insulin resistance that is also a hallmark of PCOS, powerfully promotes fat storage in the liver. After menopause, the protective effects of estrogen decline, and the risk of MAS_LD increases significantly, making women more susceptible to the metabolic changes that lead to liver stress. In both pre- and postmenopausal women, low SHBG is an independent predictor of liver fat accumulation.

The Thyroid and Liver Connection

The liver’s influence extends to thyroid function, which governs the metabolic rate of every cell in your body. The liver is the primary site where the inactive thyroid hormone, thyroxine (T4), is converted into its active form, triiodothyronine (T3). This conversion is essential for energy production, temperature regulation, and overall metabolic health.

A liver compromised by steatosis and inflammation becomes inefficient at this vital conversion process. This can lead to a state of functional hypothyroidism, where blood tests for TSH and T4 might appear normal, but the body experiences the symptoms of an underactive thyroid because of insufficient active T3.

These symptoms include fatigue, weight gain, and brain fog. This impaired conversion further slows metabolism, exacerbating the very conditions of weight gain and insulin resistance that contribute to liver stress in the first place, tightening the dysfunctional loop.

| System | Manifestation of Liver Dysfunction | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | Elevated blood glucose and triglycerides | Selective hepatic insulin resistance and increased de novo lipogenesis. |

| Endocrine (Male) | Lower total and free testosterone, altered T/E2 ratio | Suppression of HPG axis by inflammation and reduced SHBG production. |

| Endocrine (Female) | Increased risk with hyperandrogenism (pre-menopause) and estrogen decline (post-menopause) | Direct effects of androgens on liver fat storage and loss of estrogen’s protective qualities. |

| Thyroid | Reduced conversion of T4 to active T3 | Impaired deiodinase enzyme activity in a stressed or fatty liver. |

Recognizing these interconnections is key. A protocol aimed at improving hormonal health, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for a man with clinically diagnosed hypogonadism, must be considered within the context of his liver health. Optimizing testosterone levels can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce visceral fat, which in turn can reduce the burden on the liver.

Similarly, addressing thyroid function or the hormonal imbalances of PCOS are integral parts of a holistic strategy to restore metabolic balance and, consequently, improve liver enzyme profiles over the long term.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of elevated liver enzymes requires moving beyond general associations to a detailed examination of the molecular and cellular mechanisms at play. The liver’s status is a direct reflection of the body’s systemic inflammatory and metabolic environment.

Persistently elevated aminotransferases are not merely indicators of hepatocyte damage; they are quantitative signals of underlying pathophysiological processes that link hepatic metabolism to the intricate regulatory networks of the endocrine system. The long-term consequences of this state are rooted in the progression from simple steatosis to the more aggressive non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and cirrhosis, a process profoundly modulated by hormonal signaling.

Molecular Pathogenesis of Hepatic Steatosis and Endocrine Crosstalk

At the cellular level, the development of hepatic steatosis is driven by an imbalance between fatty acid uptake, de novo lipogenesis (DNL), and fatty acid disposal through beta-oxidation or export as very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Insulin resistance is the central pathological driver. In the insulin-resistant state, peripheral adipose tissue becomes resistant to insulin’s anti-lipolytic effect, leading to an increased flux of free fatty acids (FFAs) to the liver.

Simultaneously, intra-hepatic insulin signaling becomes selectively dysregulated. While the pathway suppressing gluconeogenesis is impaired, the pathway promoting lipogenesis remains sensitive or even becomes hyperactive. This is mediated by the transcription factor Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1c (SREBP-1c), which is potently activated by insulin and drives the expression of genes involved in DNL.

The resulting accumulation of triglycerides within hepatocytes leads to lipotoxicity. This state is characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which collectively promote hepatocyte injury, inflammation, and apoptosis, leading to the release of ALT and AST into circulation.

Selective hepatic insulin resistance creates a paradoxical state of concurrent hyperglycemia and accelerated fat synthesis, driving the lipotoxicity that underlies liver enzyme elevation.

The Intricate Role of Sex Steroids and SHBG

The influence of sex steroids on liver health is mediated by their direct action on hepatocytes and their systemic metabolic effects. The liver is both a target for and a regulator of sex hormones.

Androgens and the Male Liver

In men, low serum testosterone is a robust independent predictor for NAFLD. Testosterone exerts a protective effect on the liver by improving insulin sensitivity in muscle and adipose tissue, thereby reducing the substrate flow for hepatic DNL. It also directly modulates hepatic lipid metabolism. When testosterone levels are low, the balance shifts.

This hypogonadal state is associated with increased visceral adiposity, a key source of inflammatory cytokines and FFAs that target the liver. Furthermore, studies have shown that the testosterone-to-estradiol (T/E2) ratio is a critical determinant. A low T/E2 ratio, indicative of increased peripheral aromatization of androgens to estrogens, is strongly associated with NAFLD severity in men, suggesting that the relative balance of these hormones is a key modulator of hepatic health.

Androgens, Estrogens, and the Female Liver

In women, the hormonal influence is phase-dependent. In pre-menopausal women, particularly those with PCOS, hyperandrogenism is a potent driver of NAFLD. Elevated androgens, in concert with insulin resistance, directly stimulate hepatic lipogenesis. Estrogen, conversely, is generally considered protective. It enhances insulin sensitivity and has favorable effects on lipid metabolism.

The sharp decline in estrogen production during menopause is a primary factor in the increased incidence of NAFLD in post-menopausal women. The loss of estrogen’s protective effects unmasks the underlying metabolic risks, making the liver more vulnerable to fat accumulation and inflammation.

| Biomarker | Population | Associated Finding | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Total Testosterone | Men | Increased prevalence and severity of NAFLD/MASLD. | Suggests hypogonadism as a contributing factor to metabolic liver disease. |

| Low SHBG | Men and Women | Independent predictor of NAFLD. | Reflects both hepatic dysfunction (reduced synthesis) and hyperinsulinemia. |

| Low T/E2 Ratio | Men | Inversely associated with NAFLD risk. | Indicates the importance of hormonal balance over absolute levels. |

| High Free Androgen Index (FAI) | Pre-menopausal Women | Associated with higher odds of NAFLD. | A marker of hyperandrogenism, often seen in conditions like PCOS. |

The Growth Hormone and Thyroid Axes

The liver is also central to the function of other endocrine axes, including the Growth Hormone/IGF-1 and Thyroid axes.

- Growth Hormone (GH) ∞ The GH/IGF-1 axis plays a role in regulating body composition and metabolism. GH deficiency is associated with increased visceral fat and hepatic steatosis. GH signaling in the liver is complex, but its disruption can impair lipid oxidation and contribute to fat accumulation. Peptide therapies like Sermorelin or CJC-1295/Ipamorelin, which stimulate natural GH secretion, are explored in wellness protocols for their potential to improve body composition and metabolic parameters, which could indirectly benefit liver health.

- Thyroid Hormones ∞ The liver’s role in converting T4 to the metabolically active T3 via deiodinase enzymes is critical. Chronic liver inflammation and cellular dysfunction can significantly impair this process. This enzymatic downregulation means that even with sufficient T4 production, the tissues do not receive adequate T3. This contributes to a systemic slowing of metabolism, which can worsen insulin resistance and lipid profiles, creating a feed-forward loop that further burdens the liver.

Ultimately, the long-term implications of elevated liver enzymes are systemic. They signify a state of chronic metabolic stress and inflammation that is deeply intertwined with the body’s entire endocrine regulatory system. This perspective underscores that therapeutic interventions must look beyond the liver itself.

Protocols that aim to restore hormonal balance, such as TRT in hypogonadal men, or strategies that improve insulin sensitivity and thyroid conversion, are fundamental to addressing the root cause of the hepatic stress and mitigating the risk of progression to more severe liver disease and its associated systemic comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

References

- Malik, R. & Hodgson, H. “The relationship between the thyroid gland and the liver.” QJM ∞ An International Journal of Medicine, vol. 95, no. 9, 2002, pp. 559-569.

- Pi-Sunyer, F. X. “The epidemiology of central fat distribution in relation to disease.” Nutrition reviews, vol. 62, no. 7, 2004, pp. S120-S126.

- Ballestri, S. et al. “The role of sex hormones in the development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.” Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 10, no. 6, 2016, pp. 733-748.

- Cleveland Clinic. “Elevated Liver Enzymes ∞ What Is It, Causes, Prevention & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 2021.

- Verywell Health. “Elevated Liver Enzymes and What They Might Mean.” Verywell Health, 2023.

- Loomba, R. & Sanyal, A. J. “The global pandemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease ∞ a call to action.” Hepatology, vol. 58, no. 4, 2013, pp. 1234-1237.

- Targher, G. et al. “Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among adolescents.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 95, no. 12, 2010, pp. 5181-5188.

- Kasper, P. & Martin, A. “The interplay between thyroid and liver ∞ implications for clinical practice.” Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 12, no. 4, 2017, pp. 289-299.

- Perry, R. J. et al. “Resolving the paradox of hepatic insulin resistance.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 125, no. 12, 2015, pp. 4567-4571.

- Jaruvongvanich, V. et al. “Endogenous sex hormones and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in US adults.” Liver International, vol. 44, no. 1, 2024, pp. 176-185.

Reflection

The data points on your lab report are more than numbers; they are the beginning of a conversation with your body. The knowledge you have gained about the deep connections between your liver, your metabolic state, and your hormonal systems is a powerful tool.

It shifts the perspective from one of passive concern to one of active participation in your own health narrative. Your unique physiology is the result of a lifetime of inputs, and understanding its current state is the foundational step toward optimizing its future.

This information is designed to illuminate the biological pathways at work within you. The journey to sustained well-being is a personal one, built on a foundation of deep self-knowledge and guided by clinical expertise. Consider how these interconnected systems manifest in your own experience of health. The path forward involves translating this understanding into a personalized strategy, a protocol built not just for a lab value, but for the vitality and function of your entire being.

Glossary

elevated liver enzymes

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

insulin resistance

elevated liver enzymes requires

de novo lipogenesis

hepatic steatosis

hepatic insulin resistance

sex hormone-binding globulin

sex hormones

low testosterone

liver health

polycystic ovary syndrome

insulin sensitivity

liver enzymes

associated with increased visceral