Fundamentals

That Line Item on Your Lab Report

You have likely arrived here holding a lab report, your eyes drawn to a line item that reads “Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin,” or simply SHBG. Perhaps the number next to it is flagged as high or low, and with that flag comes a cascade of quiet questions.

You may be feeling fatigued, experiencing shifts in your mood, or noticing changes in your body that do not align with your efforts in diet and exercise. These experiences are valid, and the number on that report is more than just a clinical data point; it is a key that can unlock a deeper understanding of your body’s intricate internal communication network.

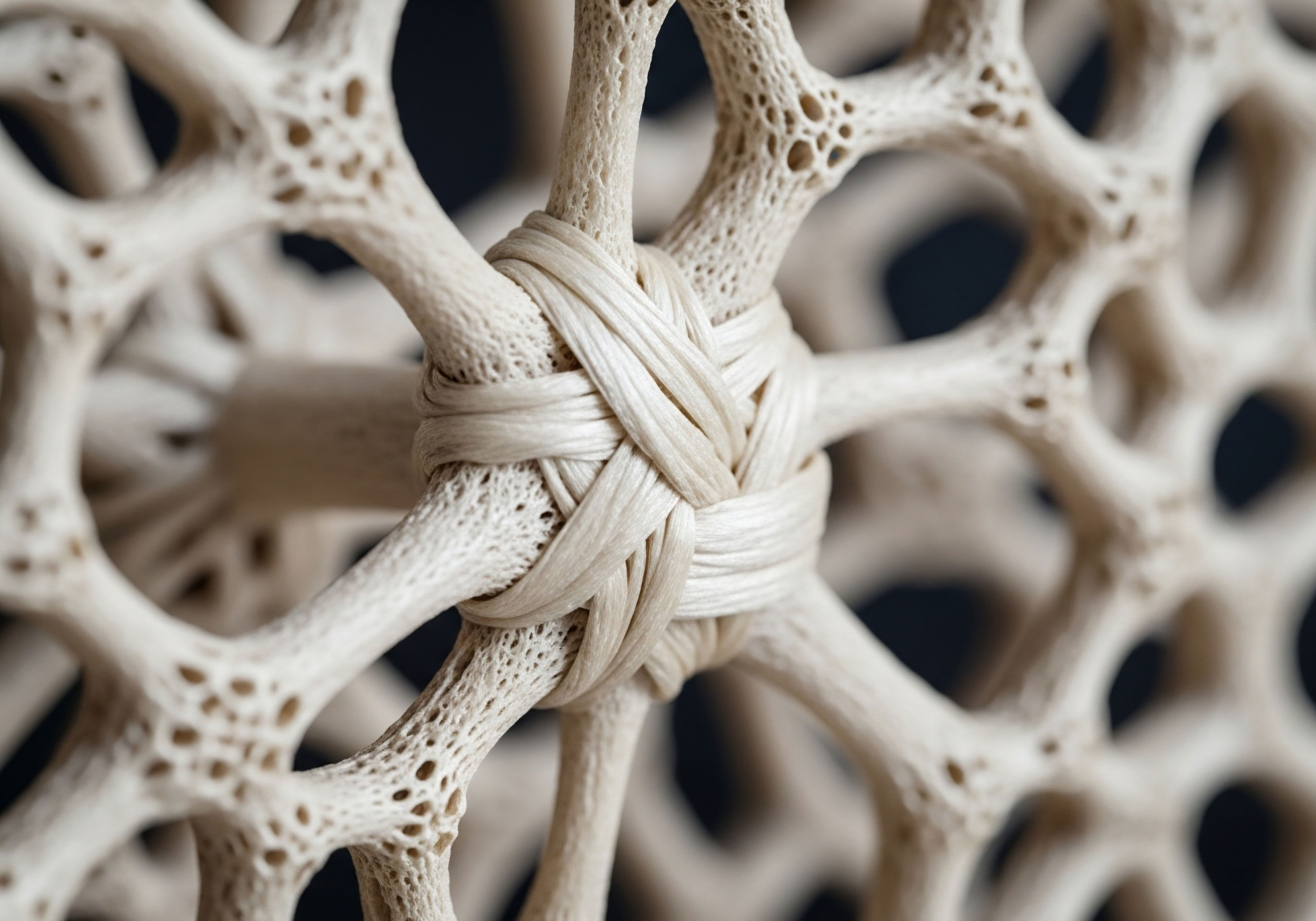

Your body operates as a finely tuned orchestra, with hormones acting as the musical score, directing everything from your energy levels to your reproductive health. SHBG is the master transporter in this system, a specialized protein produced primarily in the liver.

Its main responsibility is to bind to sex hormones ∞ chiefly testosterone and estradiol (a form of estrogen) ∞ and carry them through the bloodstream. Think of SHBG as a fleet of armored vehicles, safely transporting powerful messengers to their destinations. The hormones inside these vehicles are bound and biologically inactive.

Only the hormones that are “free,” or unbound, can exit the bloodstream, enter cells, and exert their effects. Therefore, the level of SHBG in your blood directly dictates the amount of free, usable hormones available to your tissues.

This is a critical concept ∞ your total hormone levels might be normal, but if your SHBG is too high or too low, the amount of active hormone your body can actually use is altered, leading to the very symptoms you may be experiencing.

The Concept of Bioavailability

Understanding SHBG requires a grasp of the principle of bioavailability. A hormone’s presence in the body does not guarantee its utility. The portion of a hormone that is not bound to SHBG or other proteins like albumin is what we refer to as “bioavailable.” This is the active contingent of your hormonal workforce.

When SHBG levels rise, more hormones are locked away in transit, reducing the bioavailable pool. You might have plenty of testosterone circulating in your system, but if most of it is bound to high levels of SHBG, your muscles, brain, and other tissues will not receive the signals they need to function optimally. This can manifest as fatigue, low libido, and difficulty maintaining muscle mass.

Conversely, when SHBG levels are low, a larger percentage of your hormones are free and active. In some contexts, this might seem beneficial, but the endocrine system thrives on balance. Excessively high levels of free hormones can lead to their own set of complications.

For women, low SHBG is frequently associated with conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), where elevated free testosterone can contribute to acne, irregular cycles, and other metabolic disturbances. For men, while it might temporarily increase certain androgenic effects, it is often a marker of underlying metabolic issues, such as insulin resistance. The level of SHBG is a direct reflection of your internal metabolic environment, offering profound clues about your liver health, insulin sensitivity, and overall systemic balance.

Chronically altered SHBG levels directly impact the amount of active hormones your cells can use, linking this single biomarker to your overall metabolic and hormonal well-being.

What Influences SHBG Levels?

Your SHBG level is not a static number; it is a dynamic marker that responds to a variety of physiological signals and lifestyle factors. Understanding these influences is the first step toward recalibrating your system. The liver is the primary site of SHBG synthesis, and its function is paramount. Several key factors instruct the liver to produce more or less of this critical protein:

- Insulin ∞ High levels of circulating insulin, often a result of a diet high in refined carbohydrates or underlying insulin resistance, send a strong signal to the liver to decrease SHBG production. This is a central reason why low SHBG is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

- Thyroid Hormones ∞ Your thyroid acts as the body’s metabolic thermostat. An overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) increases SHBG production, while an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) tends to lower it.

- Estrogens and Androgens ∞ These hormones create a feedback loop. Estrogens, particularly when taken orally (like in some contraceptives), stimulate the liver to produce more SHBG. Conversely, high levels of androgens, like testosterone, tend to suppress its production.

- Body Composition and Diet ∞ Higher levels of body fat, especially visceral fat around the organs, are associated with lower SHBG levels, largely due to the connection with insulin resistance. Conversely, diets rich in fiber and certain phytonutrients can support healthier SHBG levels.

- Age ∞ It is a well-documented phenomenon that SHBG levels naturally tend to increase with age in both men and women. This is one of the primary reasons why free testosterone levels decline more significantly with age than total testosterone levels.

Recognizing these connections is empowering. It transforms the number on your lab report from a source of concern into a roadmap. It tells a story about your metabolic health, your liver function, and the overall hormonal milieu of your body. By addressing the root drivers ∞ be it insulin sensitivity, thyroid function, or lifestyle factors ∞ you can begin to influence your SHBG levels and, in turn, restore the hormonal balance necessary for optimal function and vitality.

Intermediate

The Metabolic Consequences of Low SHBG

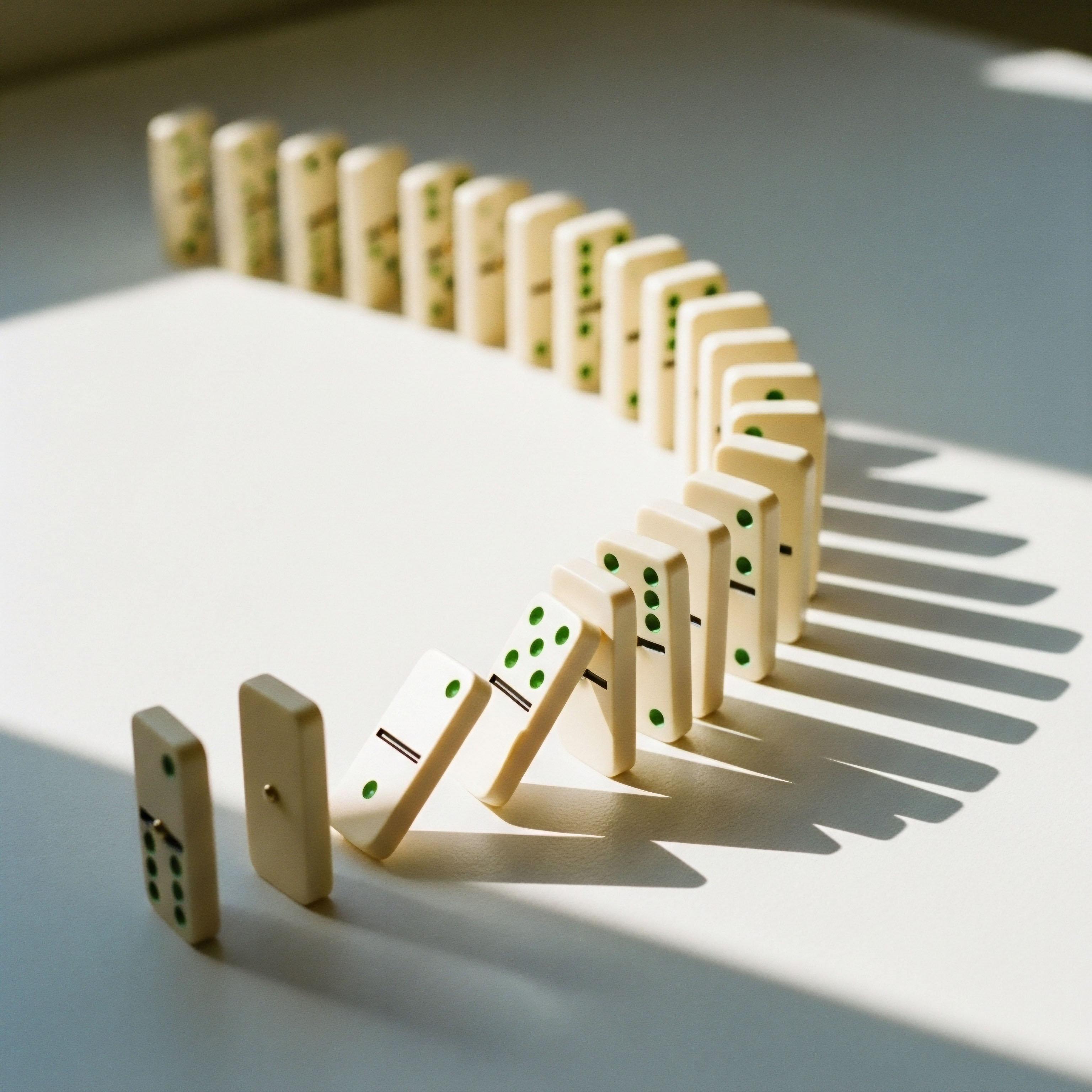

Chronically low Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin is a significant clinical indicator of underlying metabolic dysfunction. Its persistence often precedes the formal diagnosis of conditions like metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. The primary mechanism driving this connection is the relationship between SHBG and insulin.

When the body becomes resistant to insulin’s effects, the pancreas compensates by producing more of it, leading to a state of hyperinsulinemia. This excess insulin directly suppresses the gene responsible for SHBG synthesis in the liver. The result is a lower-than-optimal level of SHBG in the bloodstream.

This state creates a self-perpetuating cycle. With less SHBG available, the proportion of free testosterone and estradiol increases. While this might sound advantageous, particularly for men, the elevated free hormone levels can exacerbate insulin resistance, especially in the context of excess visceral adipose tissue.

In women, the combination of low SHBG and consequently higher free androgen levels is a cornerstone of the pathophysiology of PCOS, contributing not only to reproductive symptoms but also to a heightened risk of lifelong metabolic disease. The long-term implications extend to cardiovascular health.

Low SHBG is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis, hypertension, and adverse cardiovascular events. It serves as a barometer of metabolic health, with its low reading signaling a systemic environment characterized by inflammation, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia.

Low SHBG is a critical biomarker for metabolic syndrome, reflecting a state of hyperinsulinemia that increases the risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The Clinical Picture of High SHBG

Conversely, chronically elevated SHBG levels present a different, yet equally significant, set of challenges. High SHBG effectively sequesters sex hormones, drastically reducing their bioavailability. In men, this can induce a state of functional hypogonadism, where total testosterone levels may appear normal or even robust, but free testosterone is insufficient to carry out its essential functions.

The clinical presentation mirrors that of true testosterone deficiency ∞ persistent fatigue, loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia), cognitive fog, depressive moods, and diminished libido. For aging men, this is particularly relevant, as the natural age-related rise in SHBG can accelerate the onset of andropause symptoms.

In women, particularly during the peri- and post-menopausal transitions, high SHBG can exacerbate symptoms. By binding tightly to the already declining levels of estrogen and testosterone, it can worsen hot flashes, accelerate bone density loss, and contribute to vaginal dryness and low libido.

The causes of elevated SHBG are varied, ranging from an overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism) and liver disease to certain medications, like oral estrogens, and conditions like anorexia nervosa. From a clinical perspective, simply measuring total testosterone is insufficient. A comprehensive hormonal assessment must include SHBG to calculate bioavailable testosterone, providing a true picture of the hormonal environment at the cellular level.

How Do Altered SHBG Levels Impact Hormone Therapies?

The baseline SHBG level is a critical variable in tailoring hormonal optimization protocols for both men and women. Ignoring it can lead to suboptimal outcomes or unexpected side effects. For a man with high baseline SHBG who begins Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), a standard dose of testosterone cypionate might be insufficient.

The high SHBG will bind a large portion of the administered testosterone, preventing it from being converted to its free, active form. In these cases, clinicians may need to adjust the dosage or frequency of administration to overcome the high binding capacity. Sometimes, addressing the root cause of the high SHBG (e.g. managing hyperthyroidism) is a necessary first step.

In contrast, a man with low SHBG starting TRT may be more sensitive to standard doses. With less SHBG to buffer the exogenous testosterone, free testosterone levels can rise rapidly. This increases the potential for side effects related to androgen excess and aromatization, where testosterone is converted into estrogen.

These individuals may require lower or less frequent doses and careful monitoring of estrogen levels, potentially necessitating the use of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to manage side effects like water retention or gynecomastia.

For women undergoing hormonal therapy, the principles are similar. A woman with high SHBG may require slightly higher doses of testosterone or estrogen to achieve symptomatic relief. Conversely, a woman with low SHBG, often seen in the context of metabolic syndrome, needs a more cautious approach. The goal is to restore balance without exacerbating the underlying drivers of low SHBG, such as insulin resistance.

| SHBG Level | Primary Metabolic Association | Long-Term Risks in Men | Long-Term Risks in Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronically Low | Insulin Resistance, Hyperinsulinemia | Increased risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, Metabolic Syndrome, potential for increased aromatization on TRT. | Increased risk of PCOS, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, Endometrial Hyperplasia. |

| Chronically High | Reduced Hormone Bioavailability | Symptoms of Hypogonadism (fatigue, muscle loss, low libido), Osteoporosis, Frailty, potential for reduced efficacy of TRT. | Exacerbation of Menopausal Symptoms, Osteoporosis, Low Libido, potential for Cognitive Decline. |

Academic

SHBG as an Active Signaling Molecule

For many years, the scientific understanding of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin was confined to its role as a passive transport protein for sex steroids. This perspective, while accurate, is incomplete. A growing body of evidence reveals that SHBG is an active participant in cellular signaling, possessing its own specific membrane receptor, known as SHBG-R.

The discovery of this receptor fundamentally shifted the paradigm, suggesting that the SHBG-steroid complex can initiate intracellular signaling cascades independent of the classical genomic pathways used by free hormones. This function adds a significant layer of complexity to the long-term implications of altered SHBG levels.

When a steroid, such as testosterone or estradiol, is bound to SHBG, the entire complex can dock with the SHBG-R on the surface of certain cells. This binding event triggers a rapid increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a ubiquitous second messenger molecule.

The activation of the cAMP pathway can influence a vast array of cellular processes, including gene expression, cell proliferation, and metabolic function. This mechanism means that SHBG is not merely a regulator of hormone availability; it is a direct hormonal actor in its own right.

For instance, in prostate and breast tissues, the SHBG-estradiol complex binding to SHBG-R has been shown to inhibit the proliferative effects of estrogen, suggesting a protective role against hormone-sensitive cancers. This provides a potential mechanistic explanation for the epidemiological data linking high SHBG levels to a reduced risk of these malignancies.

The Interplay of SHBG Inflammation and Genetics

Chronically altered SHBG levels are deeply interwoven with the body’s inflammatory status. Low SHBG is a consistent feature of chronic low-grade inflammatory states, which are characteristic of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), have been shown in vitro to directly suppress the expression of the SHBG gene in liver cells. This establishes a bidirectional, deleterious relationship ∞ the metabolic state associated with low SHBG promotes inflammation, and the resulting inflammatory mediators further suppress SHBG production.

This connection has profound long-term consequences. A persistently low SHBG level can be viewed as a biomarker of sustained systemic inflammation, a root cause of numerous chronic diseases, from atherosclerosis to neurodegenerative conditions. The increased bioavailability of sex steroids in a low-SHBG state may also contribute to this inflammatory milieu, as androgens can have pro-inflammatory effects in certain tissues and cellular contexts.

The function of SHBG extends beyond hormone transport; it acts as a direct signaling molecule and its levels are intricately linked with systemic inflammation and genetic predispositions.

Furthermore, individual genetic variations play a significant role in determining baseline SHBG levels and an individual’s response to environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in or near the SHBG gene that are strongly associated with circulating SHBG concentrations.

These genetic variants can explain a substantial portion of the inter-individual variability in SHBG levels. For example, certain polymorphisms may result in a constitutionally lower or higher SHBG level, predisposing an individual to the long-term health consequences associated with that state.

This genetic lens is critical for personalized medicine; a person with a genetic predisposition to low SHBG may need to be particularly vigilant about maintaining insulin sensitivity and a healthy body weight to mitigate their inherent risk for metabolic disease.

What Are the Implications for Advanced Therapeutic Protocols?

This deeper understanding of SHBG’s role as a signaling molecule and its connection to inflammation and genetics has direct implications for advanced therapeutic interventions, including peptide therapies. For instance, therapies aimed at improving insulin sensitivity, such as the use of GLP-1 agonists or peptides like Tesamorelin (often used for visceral fat reduction in specific populations), can indirectly but powerfully modulate SHBG levels.

By reducing insulin resistance and visceral adiposity, these interventions can alleviate the suppressive pressure on SHBG gene expression in the liver, leading to a healthier SHBG level and improved hormonal balance.

This creates a more holistic view of treatment. Instead of just replacing a deficient hormone, the goal becomes to restore the optimal function of the entire endocrine and metabolic system. The table below outlines some of these advanced concepts and their clinical relevance.

| Concept | Mechanism | Long-Term Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| SHBG-R Signaling | The SHBG-steroid complex binds to a membrane receptor (SHBG-R), activating intracellular cAMP pathways. | Suggests a protective, anti-proliferative role in hormone-sensitive tissues. Chronically low SHBG may mean a loss of this protective signaling. |

| Inflammatory Suppression | Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-α) directly inhibit SHBG gene expression in hepatocytes. | Low SHBG acts as a biomarker for chronic systemic inflammation, a driver of atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, and other age-related diseases. |

| Genetic Polymorphisms | Variations (SNPs) in the SHBG gene influence baseline circulating levels of the protein. | Explains inter-individual differences and can identify individuals with a genetic predisposition to the metabolic consequences of low or high SHBG. |

| Therapeutic Modulation | Interventions that improve insulin sensitivity (e.g. peptide therapy, lifestyle changes) can increase SHBG production. | Provides a strategy to correct SHBG levels by addressing root metabolic causes, leading to more sustainable and systemic health improvements. |

Ultimately, the long-term implications of altered SHBG levels are far-reaching. This single protein sits at the crossroads of endocrinology, metabolism, and immunology. Its measurement provides a window into an individual’s risk for a spectrum of chronic diseases, and its modulation represents a powerful target for interventions aimed at promoting longevity and optimizing health.

References

- Simó, Rafael, et al. “Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin ∞ A Key Player in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 104, no. 12, 2019, pp. 5963-5978.

- Hammond, Geoffrey L. “Diverse Roles of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin in Health and Disease.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 419, 2016, pp. 183-194.

- Pugeat, Michel, et al. “Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) ∞ From a Past of Transport to a Future of Cellular Signaling.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 72, no. 5, 2010, pp. 575-585.

- Wallace, I. R. et al. “Sex Hormone Binding Globulin and Insulin Resistance.” Clinical Endocrinology, vol. 78, no. 3, 2013, pp. 321-329.

- Selva, D. M. and G. L. Hammond. “Thyroxine-Binding Globulin, Transthyretin, and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin ∞ A Family of Secreted Proteins with Diverse Functions.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 201, no. 3, 2009, pp. 305-316.

- Laurent, M. R. et al. “Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin as a Marker of Health and Morbidity in Older Men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 1, 2016, pp. 31-41.

- Deslypere, J. P. and A. Vermeulen. “Leydig Cell Function in Normal Men ∞ Effect of Age, Life-Style, Residence, Diet, and Activity.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 59, no. 5, 1984, pp. 955-962.

- Perry, J. R. B. et al. “Genetic Regulation of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin ∞ A Genome-Wide Association Study in 11,000 European Women.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 95, no. 7, 2010, pp. 3457-3465.

Reflection

From Data Point to Personal Insight

You began this exploration with a number on a page, a clinical marker that may have felt abstract or alarming. Throughout this discussion, we have translated that data point into a narrative about your body’s internal ecosystem.

The level of SHBG in your blood is not a final judgment on your health; it is a dynamic signal, a piece of intelligence from the front lines of your metabolic and hormonal systems. It tells a story of how your body is responding to your diet, your stress levels, your age, and your unique genetic blueprint.

The knowledge you now possess is the foundation for meaningful action. It allows you to ask more precise questions and to understand the ‘why’ behind the symptoms you may be feeling. This understanding shifts the dynamic from one of passive concern to active participation in your own wellness.

The path forward involves looking beyond a single number and seeing the interconnected systems it represents. It invites a conversation, not just about correcting a value, but about recalibrating the entire system to support your long-term vitality. Your biology is not your destiny; it is your biography, and you are an active author in the chapters yet to be written.