Fundamentals

Have you ever felt a subtle shift in your energy, a change in your mood, or a persistent difficulty with your weight, despite your best efforts? Perhaps you experience unpredictable sleep patterns or a sense of unease that seems to defy simple explanations.

These sensations, often dismissed as typical aspects of aging or daily stress, frequently point to deeper biological conversations happening within your body. Your personal experience of these symptoms is a valid signal, a message from your internal systems seeking balance. Understanding these signals, particularly how your dietary choices influence your hormonal landscape, marks a significant step toward reclaiming your vitality.

Our bodies possess an intricate communication network, the endocrine system, which relies on chemical messengers known as hormones. These hormones orchestrate nearly every physiological process, from metabolism and mood to sleep and reproductive function. The food we consume provides not only the building blocks for our cells but also critical signals that either support or disrupt this delicate hormonal symphony.

Over time, specific dietary patterns can profoundly alter these internal communications, leading to long-term effects that manifest as the very symptoms you might be experiencing.

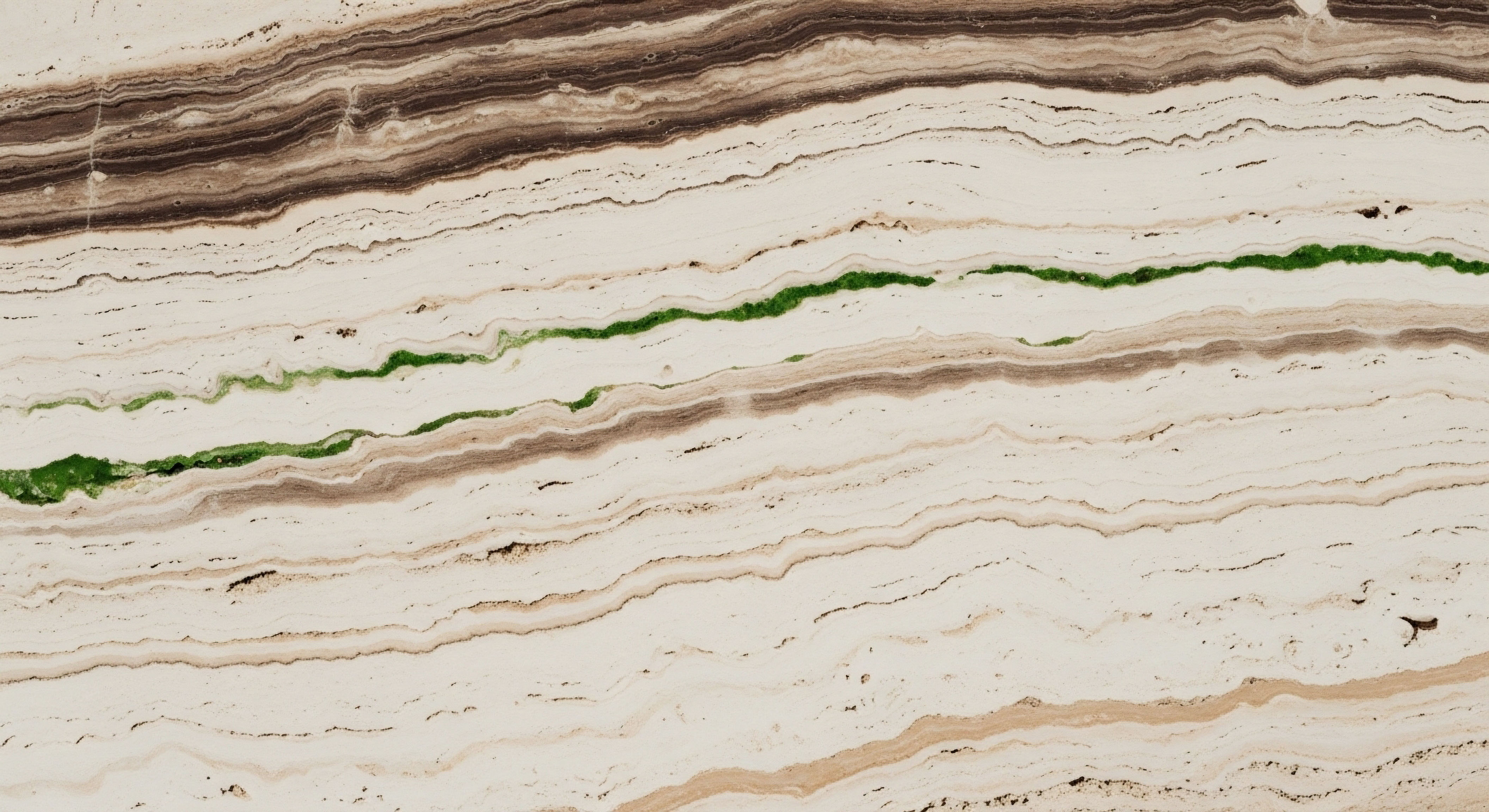

Dietary choices act as powerful signals, influencing the body’s intricate hormonal communication network over time.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

Consider hormones as the body’s internal messaging service, carrying instructions from one organ to another. When you consume food, you initiate a cascade of these messages. For instance, eating carbohydrates triggers the release of insulin from the pancreas, a hormone essential for regulating blood sugar and directing energy into cells.

Consuming fats and proteins influences satiety hormones like leptin and ghrelin, which govern hunger and fullness signals. These immediate responses, when repeated consistently through a particular dietary pattern, begin to shape the long-term behavior of your endocrine glands and their output.

A diet consistently high in refined carbohydrates, for example, can lead to chronic elevation of insulin levels. Over time, cells may become less responsive to insulin’s signals, a condition known as insulin resistance. This state not only affects blood sugar regulation but also impacts other hormones, including sex hormones and adrenal hormones, creating a ripple effect across the entire system.

Conversely, dietary patterns that promote stable blood sugar, such as those emphasizing whole, unprocessed foods, can foster greater insulin sensitivity and support overall hormonal equilibrium.

Dietary Patterns and Hormonal Balance

The relationship between what you eat and how your hormones function is dynamic and reciprocal. Your diet provides the raw materials for hormone synthesis, influences the enzymes that activate or deactivate hormones, and impacts the pathways through which hormones are transported and cleared from the body.

A consistent intake of nutrient-dense foods supplies the necessary cofactors for healthy hormone production. Conversely, diets lacking essential nutrients or abundant in inflammatory compounds can create systemic stress, forcing the endocrine system to adapt in ways that may not be optimal for long-term health.

Understanding these foundational connections is the first step toward a more personalized approach to wellness. It moves beyond generic dietary advice, inviting you to observe how your unique biological system responds to different foods, empowering you to make choices that truly support your hormonal health and overall well-being.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding, we can explore how specific dietary patterns exert their long-term influence on hormonal regulation, delving into the clinical implications and the mechanisms at play. The body’s endocrine system operates through intricate feedback loops, similar to a sophisticated thermostat system. Dietary inputs can either fine-tune this thermostat or send disruptive signals, leading to chronic imbalances that manifest as persistent symptoms.

Ketogenic Dietary Patterns and Endocrine Adaptation

A ketogenic diet, characterized by very low carbohydrate intake, moderate protein, and high fat, induces a metabolic state where the body primarily burns fat for fuel, producing ketones. This dietary approach significantly impacts several hormonal axes. A primary effect involves a substantial reduction in insulin levels due to minimal carbohydrate consumption.

This can be particularly beneficial for individuals with insulin resistance or conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), where high insulin often drives elevated androgen levels. Studies indicate that a ketogenic diet can lower insulin, reduce testosterone, and promote more regular ovulation in women with PCOS.

Yet, the long-term effects of ketogenic diets can vary, especially for women. Some research suggests that prolonged carbohydrate restriction may increase cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. While acute, controlled stress can be hormetic, chronic cortisol elevation may contribute to weight gain, particularly around the midsection, and affect mood regulation.

Additionally, thyroid function may decrease with prolonged calorie restriction, though it often recovers upon reintroduction of adequate calories. The body’s sensitivity to perceived nutrient scarcity can influence reproductive hormones, potentially impacting menstrual cycle regularity and DHEA levels in some women.

Ketogenic diets significantly lower insulin, benefiting conditions like PCOS, but long-term application requires careful monitoring of cortisol and thyroid function, especially in women.

High Carbohydrate Dietary Patterns and Metabolic Hormones

Conversely, dietary patterns rich in carbohydrates, particularly refined varieties, have distinct hormonal consequences. A consistent intake of highly processed carbohydrates leads to frequent and pronounced spikes in blood glucose, necessitating a sustained release of insulin. Over time, this can lead to diminished insulin sensitivity, requiring the pancreas to produce even more insulin to maintain normal blood sugar levels. This state of hyperinsulinemia is a precursor to metabolic dysfunction and can influence other hormonal pathways.

Research indicates that a refined high-carbohydrate diet can be associated with visceral obesity and alterations in the serotonin pathway, potentially impacting satiety and hunger signals. While some studies suggest that higher carbohydrate intake, when isocaloric, may not differentially affect testosterone or SHBG in men compared to higher protein diets, a low-fat, high-carbohydrate approach has been linked to lower estradiol and progesterone levels in premenopausal women, potentially reducing breast cancer risk.

The quality of carbohydrates matters immensely; whole grains and fiber-rich sources elicit different hormonal responses than refined sugars and starches.

The Role of Macronutrient Ratios and Specific Nutrients

The balance of macronutrients ∞ proteins, fats, and carbohydrates ∞ within a dietary pattern profoundly shapes hormonal responses.

Dietary Fat and Sex Hormones

The type and quantity of dietary fat play a significant role in sex hormone regulation. Low-fat diets have been associated with decreased testosterone levels in men, with some studies suggesting a more pronounced effect in men of European ancestry.

Conversely, higher fat intake, particularly from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), has been linked to slightly increased testosterone concentrations in healthy women. Saturated fatty acids may also influence sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and total testosterone in men when replacing protein calories. These findings underscore the importance of adequate, healthy fat intake for supporting sex hormone production and balance.

Protein Intake and Growth Factors

Protein intake directly influences growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) secretion. Adequate protein is essential for stimulating GH release, particularly certain amino acids like arginine, histidine, and lysine. GH and IGF-1 are critical for protein synthesis, muscle maintenance, and overall metabolic regulation.

Periods of protein deficiency can lead to reduced IGF-1 levels, affecting the body’s anabolic capacity. Furthermore, protein-rich meals can stimulate the release of satiety-promoting peptides like peptide-tyrosine-tyrosine (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), influencing appetite regulation.

Fiber and Estrogen Metabolism

Dietary fiber, often overlooked, holds a significant role in estrogen metabolism. Fiber binds to estrogen in the intestine, facilitating its excretion and reducing its reabsorption, thereby potentially lowering circulating estrogen levels. This mechanism is particularly relevant for conditions linked to estrogen dominance.

A high-fiber diet can alter the gut microbiota, which in turn influences the activity of enzymes like beta-glucuronidase that can deconjugate estrogen, allowing its reabsorption. Therefore, a diet rich in diverse fiber sources supports healthy estrogen balance and detoxification pathways.

| Dietary Component | Primary Hormonal Impact | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Low Carbohydrate / Ketogenic | Reduced insulin, altered ghrelin/leptin, potential cortisol/thyroid shifts | Insulin sensitivity, PCOS management, weight regulation; monitor adrenal/thyroid health |

| High Refined Carbohydrate | Elevated insulin, potential insulin resistance, serotonin pathway changes | Metabolic dysfunction, visceral adiposity, appetite dysregulation |

| Adequate Healthy Fats | Supports sex hormone production (testosterone, estrogen) | Reproductive health, libido, bone density; crucial for men’s testosterone |

| Sufficient Protein | Stimulates growth hormone, IGF-1, satiety peptides (PYY, GLP-1) | Muscle mass, metabolic rate, appetite control, cellular repair |

| High Fiber | Modulates estrogen excretion, influences gut microbiome | Estrogen balance, detoxification, gut health, breast cancer risk |

Intermittent Fasting and Endocrine Rhythms

Intermittent fasting (IF), which involves alternating periods of eating and fasting, influences hormonal circadian rhythms. During fasting windows, insulin levels decrease significantly, leading to improved insulin sensitivity. This metabolic shift encourages the body to tap into stored fat for energy. Additionally, IF can alter hunger hormones, potentially decreasing ghrelin and enhancing leptin sensitivity, contributing to reduced appetite and improved satiety.

However, the effects of IF can be highly individualized, particularly for women. While some women experience benefits, others may find it too stressful, leading to increased cortisol and potential disruptions to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which governs reproductive hormones. Prolonged or overly restrictive fasting might impact DHEA levels and thyroid function, which are sensitive to perceived energy availability. Tailoring fasting protocols to individual physiology and hormonal status is paramount.

Academic

A deeper examination of dietary patterns reveals their profound and interconnected influence on the endocrine system, extending beyond simple macronutrient effects to encompass complex systems biology. The long-term hormonal consequences of specific dietary choices are not isolated events; they represent a continuous dialogue between nutrient signaling, genetic expression, and the intricate feedback mechanisms governing metabolic and reproductive health.

Dietary Lipids, Steroidogenesis, and Androgen Metabolism

The composition of dietary fats directly impacts steroidogenesis, the biochemical pathway that produces steroid hormones, including androgens and estrogens. Cholesterol, derived from dietary sources and endogenous synthesis, serves as the precursor for all steroid hormones. Therefore, the availability and type of dietary lipids can influence the raw materials for hormone production.

Studies have demonstrated a clear association between dietary fat intake and circulating androgen levels. A meta-analysis of intervention studies indicated that low-fat diets significantly decrease total and free testosterone in men. This effect may be more pronounced in men of European ancestry, suggesting genetic or environmental modifiers.

The proposed mechanisms include alterations in cholesterol availability for steroid synthesis, changes in membrane fluidity of steroidogenic cells, and shifts in the activity of enzymes involved in testosterone production or metabolism. Conversely, higher intakes of saturated fatty acids, when isocalorically replacing protein, have been linked to elevated SHBG and total testosterone levels in men. This complex interplay suggests that the quality and quantity of dietary fats are critical modulators of male endocrine health.

For women, the relationship between dietary fat and androgens also exists. Higher total fat intake, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), has been positively associated with total and free testosterone concentrations in regularly menstruating women. This highlights that optimal fat intake is not merely about avoiding deficiency but about providing specific lipid profiles that support healthy hormonal milieu for both sexes.

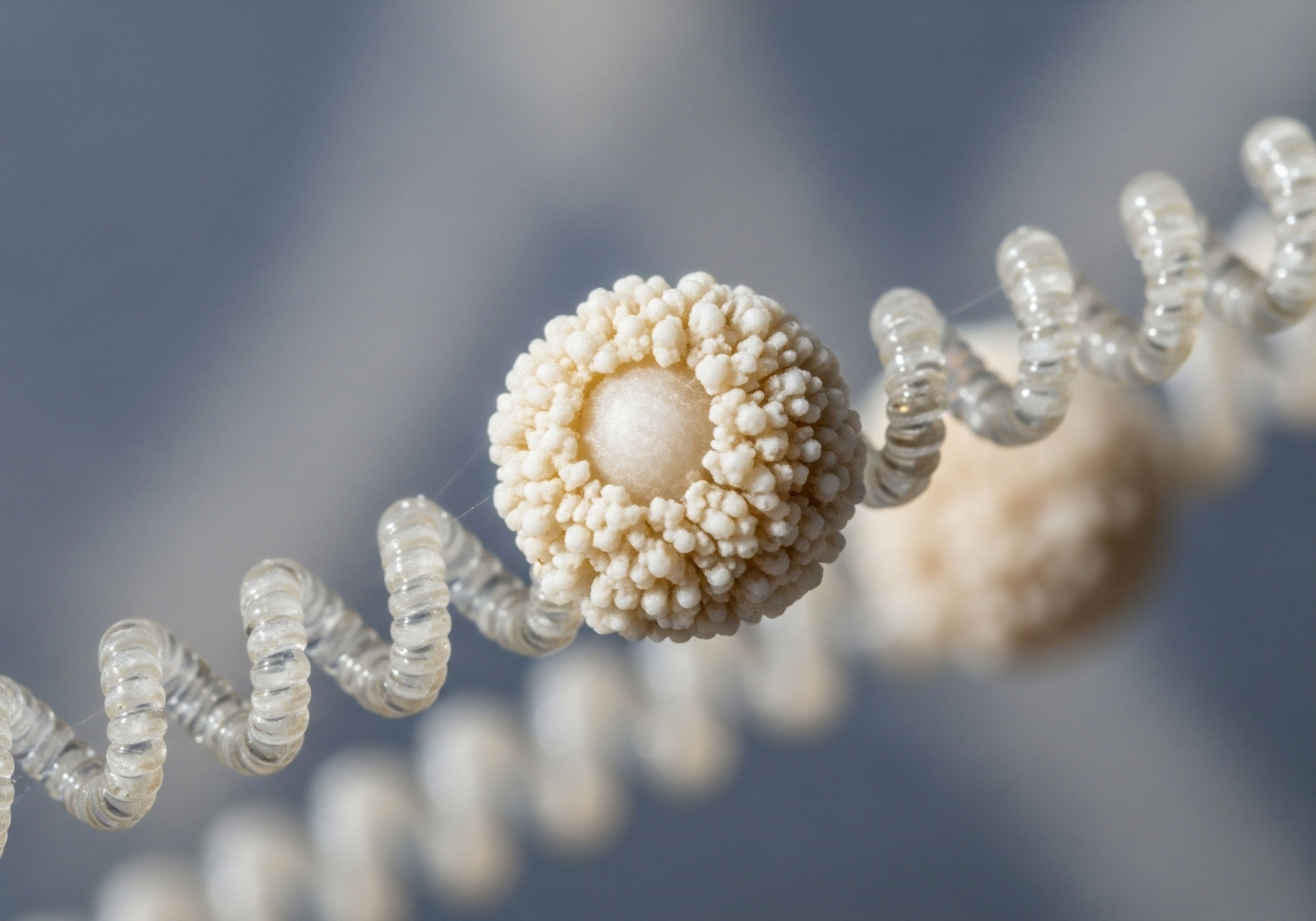

The Gut Microbiome as an Endocrine Organ

The human gut microbiome, a vast ecosystem of microorganisms, acts as a virtual endocrine organ, profoundly influencing host hormone metabolism. This interaction is particularly evident in estrogen metabolism. After estrogens are metabolized in the liver and conjugated for excretion, they are transported to the intestine.

Certain gut bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which can deconjugate these estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into circulation. This process, if excessive, can lead to higher circulating estrogen levels, a state sometimes referred to as “estrogen dominance,” which has implications for conditions like breast cancer risk.

Dietary fiber plays a crucial role in modulating this gut-hormone axis. A high-fiber diet promotes a diverse and healthy gut microbiome, which can reduce the activity of beta-glucuronidase, thereby facilitating the proper excretion of estrogens.

Different types of fiber may have varying effects on estrogen metabolites, with some studies suggesting that fiber from fruits and vegetables may lead to more favorable estrogen profiles. This underscores that dietary patterns influence hormonal health not only through direct nutrient provision but also by shaping the microbial environment that governs hormone recycling and elimination.

Processed Foods and Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

A significant, yet often overlooked, long-term hormonal effect of modern dietary patterns stems from the pervasive presence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in processed foods and their packaging. EDCs are exogenous substances that interfere with the normal function of the endocrine system, leading to adverse health outcomes.

Common EDCs found in processed foods include:

- Phthalates ∞ Often found in plastic packaging, these can leach into fatty foods and interfere with hormone signaling, impacting reproductive function and metabolic health.

- Bisphenol A (BPA) ∞ Present in the linings of food and beverage cans, BPA can mimic estrogen, disrupting hormonal balance and contributing to obesity and cancer risk.

- Artificial Dyes and Sweeteners ∞ Substances like tartrazine (Yellow 5) and erythrosine (Red 3) have been associated with endocrine-disrupting effects, potentially interfering with thyroid hormone synthesis and overall hormonal regulation.

- Parabens ∞ Used as preservatives, these can also exhibit estrogenic activity, adding to the body’s overall endocrine burden.

Long-term exposure to these compounds, even at low levels, can accumulate and disrupt hormone synthesis, receptor binding, and signal transduction pathways, leading to chronic hormonal imbalances. This systemic interference can manifest as metabolic disorders, reproductive issues, and an increased risk of hormone-related cancers. The high consumption of ultra-processed foods, which are often packaged in EDC-containing materials and contain numerous additives, represents a significant public health concern for long-term endocrine health.

Chronic exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in processed foods can subtly yet profoundly interfere with hormonal signaling, contributing to metabolic and reproductive dysregulation.

Hormonal Interplay and Clinical Protocols

The insights gained from understanding these long-term dietary effects directly inform personalized wellness protocols, including hormone optimization strategies. For instance, addressing insulin resistance through dietary modification (e.g. reducing refined carbohydrates, increasing fiber) can enhance the efficacy of Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in men by improving cellular responsiveness and reducing inflammation that might otherwise impede hormone action.

Similarly, for women undergoing hormonal balance protocols for peri- or post-menopause, optimizing gut health through fiber-rich diets can support the proper metabolism and excretion of administered hormones like progesterone or low-dose testosterone, ensuring their intended physiological impact.

| Dietary Pattern/Component | Affected Hormonal Axis/System | Mechanism of Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Refined Carbohydrate Intake | Insulin-Glucagon Axis, HPG Axis, Adrenal Axis | Sustained hyperinsulinemia leads to insulin resistance, impacting sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and increasing adrenal androgen production; chronic metabolic stress elevates cortisol. |

| Low-Fat Diets (Men) | HPG Axis (Testosterone, Dihydrotestosterone) | Reduced cholesterol availability for steroidogenesis; potential alterations in enzyme activity involved in testosterone synthesis. |

| High Fiber Intake | Estrogen Metabolism, Gut-Brain Axis | Modulates gut microbiome, reducing beta-glucuronidase activity and promoting fecal estrogen excretion; influences short-chain fatty acid production impacting systemic inflammation. |

| Protein Deficiency | Growth Hormone-IGF-1 Axis | Insufficient amino acid availability impairs growth hormone and IGF-1 synthesis, affecting protein anabolism and cellular repair. |

| Processed Foods (EDCs) | Thyroid Axis, Reproductive Hormones, Metabolic Hormones | EDCs mimic or block hormone receptors, interfere with hormone synthesis/metabolism, and disrupt signal transduction pathways, leading to widespread endocrine dysfunction. |

The integration of dietary science with advanced clinical protocols, such as Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy (e.g. Sermorelin, Ipamorelin/CJC-1295) or targeted Testosterone Cypionate injections, becomes more effective when the underlying metabolic and endocrine environment is optimized through nutrition.

For instance, ensuring adequate protein intake supports the efficacy of growth hormone-releasing peptides by providing the necessary building blocks for protein synthesis and tissue repair. Similarly, managing inflammation through dietary choices can enhance the body’s response to peptides like Pentadeca Arginate (PDA), which targets tissue repair and inflammation.

Understanding the deep, reciprocal relationship between dietary patterns and long-term hormonal health empowers individuals to make informed choices that support not only symptom resolution but also sustained physiological resilience. This approach moves beyond temporary fixes, aiming for a recalibration of the body’s innate systems.

References

- Whittaker, Joseph, and Stephen D. O’Keefe. “Low-fat diets and testosterone in men ∞ Systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies.” Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 210 (2021) ∞ 105878.

- Hamdy, Osama, and Sherita Hill Golden. “Effects of Growth Hormone on Glucose, Lipid, and Protein Metabolism in Human Subjects.” Endocrine Reviews 21, no. 1 (2000) ∞ 64-91.

- Spadaro, Paola A. Helen L. Naug, Eugene F. Du Toit, Daniel Donner, and Natalie J. Colson. “A refined high carbohydrate diet is associated with changes in the serotonin pathway and visceral obesity.” PLoS One 10, no. 10 (2015) ∞ e0140121.

- Brinkworth, Grant D. et al. “Long-Term Effects of a Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing High Protein or High Carbohydrate Weight Loss Diets on Testosterone, SHBG, Erectile and Urinary Function in Overweight and Obese Men.” PLoS One 10, no. 10 (2015) ∞ e0140121.

- Varady, Krista A. et al. “Effects of intermittent fasting on the circulating levels and circadian rhythms of hormones.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 107, no. 1 (2022) ∞ e100-e110.

- Axe, Josh. “Keto Diet ∞ Your 30-Day Plan to Lose Weight, Balance Hormones, Boost Brain Health, and Reverse Disease.” Grand Central Life & Style (2019).

- Gottfried, Sara. “Women, Food, and Hormones ∞ A 4-Week Plan to Achieve Hormonal Balance, Lose Weight, and Feel Great.” HarperOne (2021).

- Paramasivam, Anand, et al. “Additives in Processed Foods as a Potential Source of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ A Review.” Journal of Xenobiotics 14, no. 4 (2024) ∞ 90.

- Zengul, Ayse Gul. “Exploring The Link Between Dietary Fiber, The Gut Microbiota And Estrogen Metabolism Among Women With Breast Cancer.” Master’s thesis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2019.

- Dugani, Sarah, et al. “Ultra-Processed Diets and Endocrine Disruption, Explanation of Missing Link in Rising Cancer Incidence Among Young Adults.” Nutrients 15, no. 23 (2023) ∞ 4960.

Reflection

Considering the profound interplay between what you consume and your body’s hormonal orchestration, where do you stand on your own health journey? This exploration of dietary patterns and their long-term hormonal effects is not merely an academic exercise; it is an invitation to introspection. Each meal, each snack, represents a choice that either supports or challenges your intricate biological systems. Understanding these connections is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of control over your well-being.

Your body possesses an innate intelligence, constantly striving for balance. When symptoms arise, they are not random occurrences; they are signals from this intelligence, indicating areas that require attention and recalibration. This knowledge empowers you to listen more closely to those signals, to become a more informed participant in your own health narrative. The path to optimal hormonal health is deeply personal, requiring a tailored approach that respects your unique physiology and lived experience.

The information presented here serves as a guide, illuminating the complex pathways through which diet influences your endocrine system. Armed with this understanding, you can begin to make conscious choices that align with your body’s needs, moving toward a state of sustained vitality and function. Your journey toward hormonal balance is a continuous process of learning, adapting, and honoring your biological self.