The Silent Architecture of Systemic Decline

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a mental fog that clouds your sharpest thoughts, or a frustrating sense of metabolic stubbornness despite your best efforts with diet and exercise. These experiences are valid, tangible signals from a biological system under duress.

The architecture of your vitality is governed by the endocrine system, an exquisitely sensitive communication network that orchestrates your body’s vast symphony of functions through chemical messengers called hormones. This system operates with precision, relying on infinitesimally small changes in hormone levels to manage everything from your stress response to your reproductive health. When this signaling is disrupted, the consequences are felt system-wide, often manifesting as a slow, creeping erosion of well-being that is difficult to pinpoint.

Unidentified hormonal disruptors are foreign chemical agents that infiltrate this delicate network. They are the static on the line, the garbled transmissions in a system that requires absolute clarity to function. Found in countless everyday products, from plastics and cosmetics to pesticides and industrial byproducts, these endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) bear a structural resemblance to your body’s natural hormones.

This molecular mimicry allows them to bind to hormone receptors, either blocking the intended signal or initiating an inappropriate one. The result is a subtle yet persistent miscalculation in your body’s internal chemistry. Over time, this constant interference contributes to a state of systemic decline, where the body’s resilience is gradually compromised, leading to tangible, long-term health repercussions.

Understanding the Endocrine Communication Network

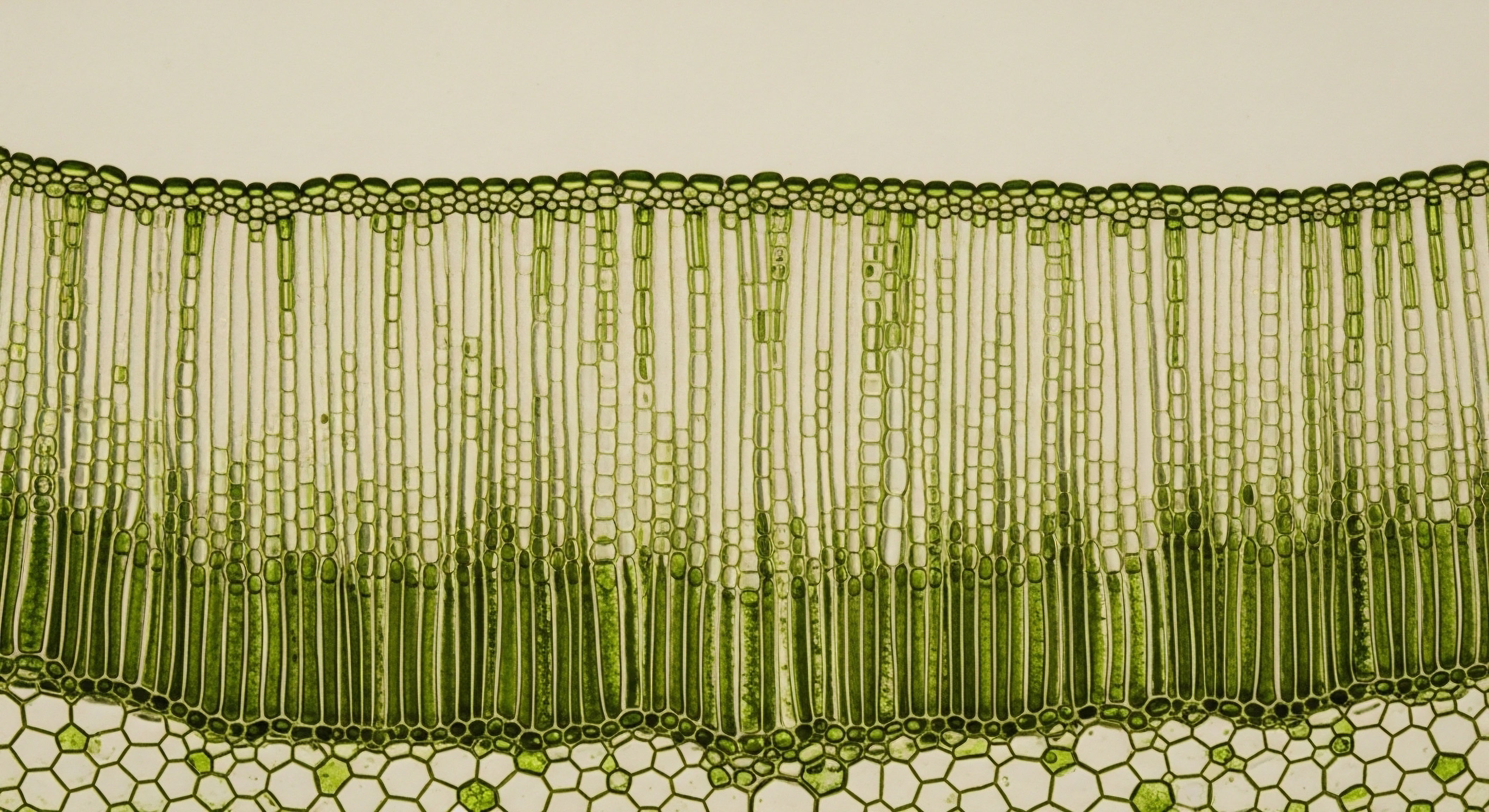

Your endocrine system is the body’s primary regulatory and communication apparatus, a collection of glands that produce hormones to coordinate physiological processes. Think of it as a wireless network transmitting vital instructions to every cell, tissue, and organ.

The pituitary gland acts as the master controller, sending signals to other glands like the thyroid, adrenals, and gonads, which in turn release their own hormones to manage metabolism, growth, stress, and reproduction. This entire structure operates on a sophisticated system of feedback loops, where the output of one gland influences the activity of another, maintaining a state of dynamic equilibrium known as homeostasis.

The body’s endocrine system depends on clear hormonal signals to regulate its most vital functions, from metabolism to reproduction.

The integrity of this network is paramount. Hormones function at incredibly low concentrations, measured in parts per billion or even trillion. This sensitivity is what makes the system so efficient, yet it is also its greatest vulnerability.

It means that even minuscule amounts of external chemicals that interfere with these signals can have disproportionately large effects, particularly when exposure is chronic and sustained over many years. The silent, cumulative nature of this disruption is what makes it so insidious; the symptoms appear gradually, disconnected from any single, identifiable cause, leaving individuals feeling unwell without a clear explanation.

How Do Hormonal Disruptors Interfere with a Healthy System?

Endocrine disruptors operate through several primary mechanisms, each one representing a distinct form of interference with your body’s internal signaling. The long-term consequences of this interference are not isolated to a single organ but ripple throughout the body’s interconnected systems, contributing to a wide range of chronic health issues.

- Signal Mimicry ∞ Many EDCs, such as Bisphenol A (BPA) found in plastics, are structurally similar to estrogen. They can bind to estrogen receptors and trigger estrogenic effects, leading to an imbalance in the body’s natural hormonal ratios. In men, this can contribute to reproductive issues, while in women it can be associated with conditions like endometriosis and certain cancers.

- Signal Blocking ∞ Some disruptors act as antagonists, occupying hormone receptors without activating them. This effectively blocks natural hormones from binding and delivering their messages. This mechanism is seen with certain pesticides that can interfere with androgen receptors, impacting male reproductive development and function.

- Metabolic Interference ∞ Other EDCs can alter the synthesis, transport, and metabolism of natural hormones. They might upregulate or downregulate the enzymes responsible for creating or breaking down hormones like cortisol or thyroid hormone, leading to either a chronic excess or a deficiency. This can have profound effects on metabolic rate, stress resilience, and overall energy levels.

The cumulative effect of this constant, low-grade interference is a progressive dysregulation of the systems that maintain health. The body is forced to constantly adapt to a noisy, unreliable internal environment. This state of chronic compensation eventually exhausts its adaptive capacity, paving the way for the development of complex, multifactorial diseases years or even decades after the initial exposures.

The Clinical Consequences of Systemic Dysregulation

The gradual accumulation of hormonal disruptors creates a state of systemic dysregulation that precedes a formal diagnosis. This is the clinical space where individuals experience a constellation of symptoms ∞ fatigue, weight gain, mood instability, cognitive difficulties ∞ that are real and disruptive, yet often lack a clear, singular cause.

From a clinical perspective, these symptoms are the logical outcomes of compromised signaling within the body’s most critical regulatory axes. The long-term repercussions are the manifestation of chronic interference with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG), Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT), and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axes, as well as the intricate pathways of metabolic health.

Understanding these pathways is essential to connecting the lived experience of feeling unwell with the underlying biological mechanisms. When a patient presents with symptoms of low testosterone, for example, a conventional approach might identify the downstream deficiency.

A systems-based perspective, informed by an understanding of EDCs, asks a deeper question ∞ what is interfering with the upstream signaling cascade that governs testosterone production? This is where the impact of unidentified disruptors becomes a central clinical consideration. They act as confounding variables, making it difficult to restore balance without addressing the persistent, low-level chemical exposures that contribute to the problem.

Impact on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

The HPG axis is the master regulator of reproductive health and steroid hormone production, including testosterone and estrogen. It is a classic feedback loop ∞ the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), prompting the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women) to produce sex hormones. Many EDCs specifically target this axis.

Chronic exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals directly impairs the body’s core hormonal feedback loops, leading to metabolic and reproductive decline.

For men, this interference can manifest as a gradual decline in testosterone levels, a condition often associated with andropause. Symptoms include low libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, and increased body fat. Clinically, protocols like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), often combined with agents like Gonadorelin to maintain the natural signaling pathway, are used to restore hormonal balance.

The presence of EDCs complicates this picture, potentially reducing the efficacy of such treatments or contributing to the underlying decline in the first place.

In women, the disruption of the HPG axis is equally significant. Interference with estrogen and progesterone signaling can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and an exacerbation of symptoms during perimenopause and menopause. Hormonal optimization protocols, which may include low-dose testosterone and progesterone, are designed to restore the balance that EDCs can disrupt. The table below outlines some common classes of disruptors and their primary impact on these vital hormonal systems.

| Disruptor Class | Common Sources | Primary Mechanism of Action | Long-Term Health Repercussions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenols (e.g. BPA) | Plastic containers, can linings, thermal paper | Estrogen receptor agonist (mimics estrogen) | Reproductive abnormalities, increased risk for certain cancers, metabolic syndrome. |

| Phthalates | Cosmetics, personal care products, vinyl plastics | Anti-androgenic (blocks testosterone signaling) | Decreased sperm quality, testicular dysgenesis, developmental issues. |

| Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) | Flame retardants in furniture and electronics | Thyroid hormone disruption | Impaired neurological development, altered metabolism, thyroid disorders. |

| Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | Non-stick cookware, water-repellent fabrics | Interferes with hormone transport and metabolism | Cardiovascular disease, immune system dysfunction, developmental problems. |

Metabolic Disruption and the Rise of Obesogens

One of the most profound long-term repercussions of unidentified hormonal disruptors is their impact on metabolic health. Certain EDCs are now classified as “obesogens” because they directly promote obesity by altering lipid metabolism and adipogenesis (the formation of fat cells). They can reprogram metabolic set-points, particularly when exposure occurs during critical developmental windows, such as in utero or early childhood. This contributes to a predisposition for weight gain and insulin resistance later in life.

Obesogens function by:

- Increasing the number of fat cells ∞ They can activate signaling pathways that cause precursor cells to differentiate into adipocytes.

- Increasing the storage of fat ∞ They can alter the metabolic machinery within fat cells to favor lipid storage over lipid breakdown.

- Altering appetite and satiety signals ∞ Some EDCs can interfere with the hormones that regulate hunger, such as leptin and ghrelin, leading to a dysregulation of energy balance.

This chemical-driven metabolic disruption provides a crucial piece of the puzzle for understanding the modern obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics. It suggests that these conditions are not solely the result of diet and lifestyle choices but are also influenced by a pervasive environmental chemical burden.

The long-term consequence is a population with a heightened susceptibility to metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol levels, all of which dramatically increase the risk for cardiovascular disease.

Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Endocrine Disruption

The most profound and scientifically compelling repercussion of endocrine disruptor exposure extends beyond the individual and into subsequent generations. This phenomenon is mediated by epigenetics, the layer of molecular instructions that sits on top of the DNA sequence and governs how genes are expressed.

Epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, can be altered by environmental exposures. Astonishingly, some of these altered marks can escape the normal process of epigenetic reprogramming that occurs during the formation of sperm and egg cells, leading to the transgenerational inheritance of disease susceptibility.

This means that the metabolic or reproductive pathologies induced by an individual’s exposure to EDCs can be passed down to their children and grandchildren, even if those descendants are never directly exposed to the original chemical.

This concept moves the discussion of hormonal disruptors from a matter of personal health to one of ancestral legacy. Seminal research in animal models has demonstrated that exposure to certain fungicides and plastics during gestation can induce reproductive defects and metabolic disorders that persist for multiple generations.

The mechanism is a permanent alteration of the epigenetic programming in the germline (the sperm or egg cells). This creates a molecular memory of the exposure that is transmitted through meiosis and fertilization, predisposing future generations to conditions like obesity, infertility, and hormone-sensitive cancers.

What Is the Mechanism of Germline Epigenetic Transmission?

The transmission of an environmental exposure’s effects across generations requires a stable alteration of the epigenome in the germline. During normal development, the vast majority of epigenetic marks are erased and reset to ensure a totipotent state in the embryo. However, certain regions of the DNA, known as “escape windows,” can evade this reprogramming. It is hypothesized that EDCs induce aberrant epigenetic marks in these specific regions of the germline DNA.

The process involves several key molecular events:

- Aberrant DNA Methylation ∞ Exposure to EDCs during critical periods of germ cell development can alter the patterns of DNA methylation, a key epigenetic mark that typically silences gene expression.

These new, environmentally induced methylation patterns can become permanently “imprinted” on the germline.

- Histone Modification ∞ The proteins that package DNA, known as histones, can be chemically modified to alter gene accessibility.

EDCs can influence the enzymes that add or remove these modifications, leading to a lasting change in the chromatin structure of sperm or eggs.

- Non-coding RNA Expression ∞ Small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) packaged within sperm can act as vectors of epigenetic information, carrying a memory of the paternal environment to the embryo and influencing its developmental trajectory.

The biological consequences of endocrine disruptor exposure can be inherited across generations through stable epigenetic modifications of the germline.

This transgenerational inheritance has profound implications for public health and our understanding of disease etiology. It suggests that the current rise in chronic diseases like diabetes, infertility, and certain cancers may be, in part, a latent consequence of chemical exposures experienced by previous generations. It reframes these conditions as having a potential environmental origin that is heritable yet independent of the classic DNA sequence-based genetics.

Case Study the Obesogen Legacy of Tributyltin (TBT)

A powerful example of this phenomenon is the obesogen tributyltin (TBT), an organotin compound used as an anti-fouling agent in marine paints. While its use is now restricted, its persistence in the environment continues to pose a threat.

Experimental studies have shown that perinatal exposure to TBT in mice leads to a dramatic increase in adipose tissue mass that persists into adulthood. This occurs because TBT activates the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a master regulator of adipogenesis, causing mesenchymal stem cells to preferentially differentiate into fat cells.

The truly significant finding is that this adipogenic phenotype is transmitted to subsequent generations that were never exposed to TBT. The F2 and F3 generations exhibit increased fat storage and altered metabolic profiles, indicating a stable epigenetic alteration in the germline of the originally exposed animal. This provides a clear molecular basis for how an environmental chemical can create a heritable, multi-generational predisposition to obesity.

| EDC Studied | Animal Model | Observed F1 Generation Effects (Direct Exposure) | Observed F3 Generation Effects (Transgenerational Inheritance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vinclozolin (Fungicide) | Rat | Decreased sperm count, increased infertility | Prostate disease, kidney disease, tumor development |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) | Mouse | Altered reproductive development, metabolic changes | Social behavioral deficits, altered pubertal onset |

| Dioxin | Rat | Pubertal abnormalities, ovarian disease | Reduced reproductive capacity, kidney abnormalities |

| Tributyltin (TBT) | Mouse | Increased adipose mass, liver abnormalities | Inherited obesity phenotype, altered stem cell differentiation |

The recognition of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance fundamentally shifts the paradigm for assessing the long-term repercussions of unidentified hormonal disruptors. The consequences are not limited to the exposed individual’s lifespan. They represent a lasting biological legacy, a chemical imprint on the health trajectory of future generations that underscores the urgent need for a more comprehensive and precautionary approach to chemical regulation and environmental health.

References

- Gore, A. C. Chappell, V. A. Fenton, S. E. Flaws, J. A. Nadal, A. Prins, G. S. Toppari, J. & Zoeller, R. T. (2015). EDC-2 ∞ The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocrine Reviews, 36(6), E1 ∞ E150.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. Bourguignon, J. P. Giudice, L. C. Hauser, R. Prins, G. S. Soto, A. M. Zoeller, R. T. & Gore, A. C. (2009). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals ∞ an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews, 30(4), 293 ∞ 342.

- Grün, F. & Blumberg, B. (2009). Endocrine disrupters as obesogens. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 304(1-2), 19 ∞ 29.

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2023). Endocrine Disruptors. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Anway, M. D. Cupp, A. S. Uzumcu, M. & Skinner, M. K. (2005). Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science, 308(5727), 1466 ∞ 1469.

- Sharpe, R. M. & Skakkebæk, N. E. (1993). Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract?. The Lancet, 341(8857), 1392 ∞ 1395.

- Heindel, J. J. & Blumberg, B. (2019). Environmental Obesogens ∞ A Unifying Theory for the Obesity Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4561.

- Crews, D. & McLachlan, J. A. (2006). Epigenetics, evolution, endocrine disruption, health, and disease. Endocrinology, 147(6 Suppl), S4-10.

The Path to Reclaiming Biological Agency

The information presented here is not intended to induce a sense of helplessness in the face of a ubiquitous chemical world. Its purpose is the opposite. Understanding the mechanisms by which your internal environment can be disrupted is the first and most critical step toward reclaiming agency over your own biology.

Your lived experience of symptoms that defy easy explanation is validated by this complex science. The path forward begins with this knowledge, transforming abstract concerns into a concrete understanding of the interplay between your body and its environment. This awareness is the foundation upon which a proactive, personalized, and deeply effective wellness strategy is built. It shifts the focus from passively accepting symptoms to actively cultivating a state of systemic resilience.