Fundamentals

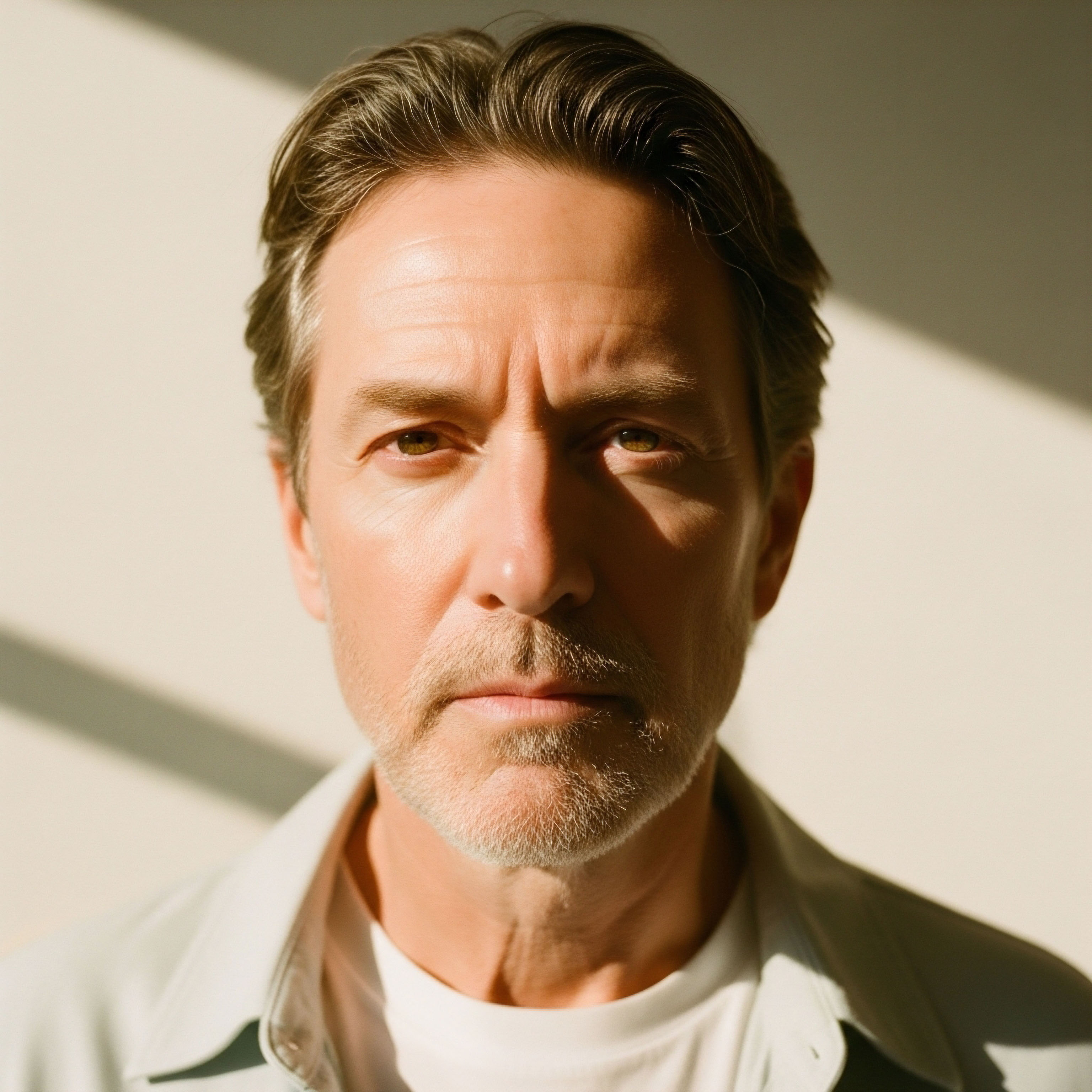

The decision to consider a protocol like medically supervised testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) often begins not with a specific number on a lab report, but with a collection of subjective feelings. It can be a persistent lack of energy that sleep doesn’t resolve, a mental fog that clouds focus, or a noticeable decline in physical strength and drive.

These experiences are valid and real. They represent a shift in your body’s internal communication system, a complex network of signals that dictates function and vitality. Understanding the long-term outcomes of intervening in this system requires first appreciating what it is we are supporting ∞ the foundational role of testosterone in maintaining biological stability.

Testosterone is a primary signaling molecule, a steroid hormone that interacts with receptors in cells throughout the body. Its influence extends far beyond sexual function. It is a key regulator of muscle mass, bone density, red blood cell production, and even cognitive processes like mood and motivation.

When the body’s ability to produce this hormone diminishes, a condition known as hypogonadism, the effects are systemic. The fatigue, the loss of muscle, the emotional changes ∞ these are direct consequences of an endocrine system struggling to maintain its equilibrium. Medically supervised TRT is a clinical intervention designed to restore this hormonal baseline, not to create a supraphysiological state, but to return the body to its intended operational parameters.

What Does Medically Supervised Mean

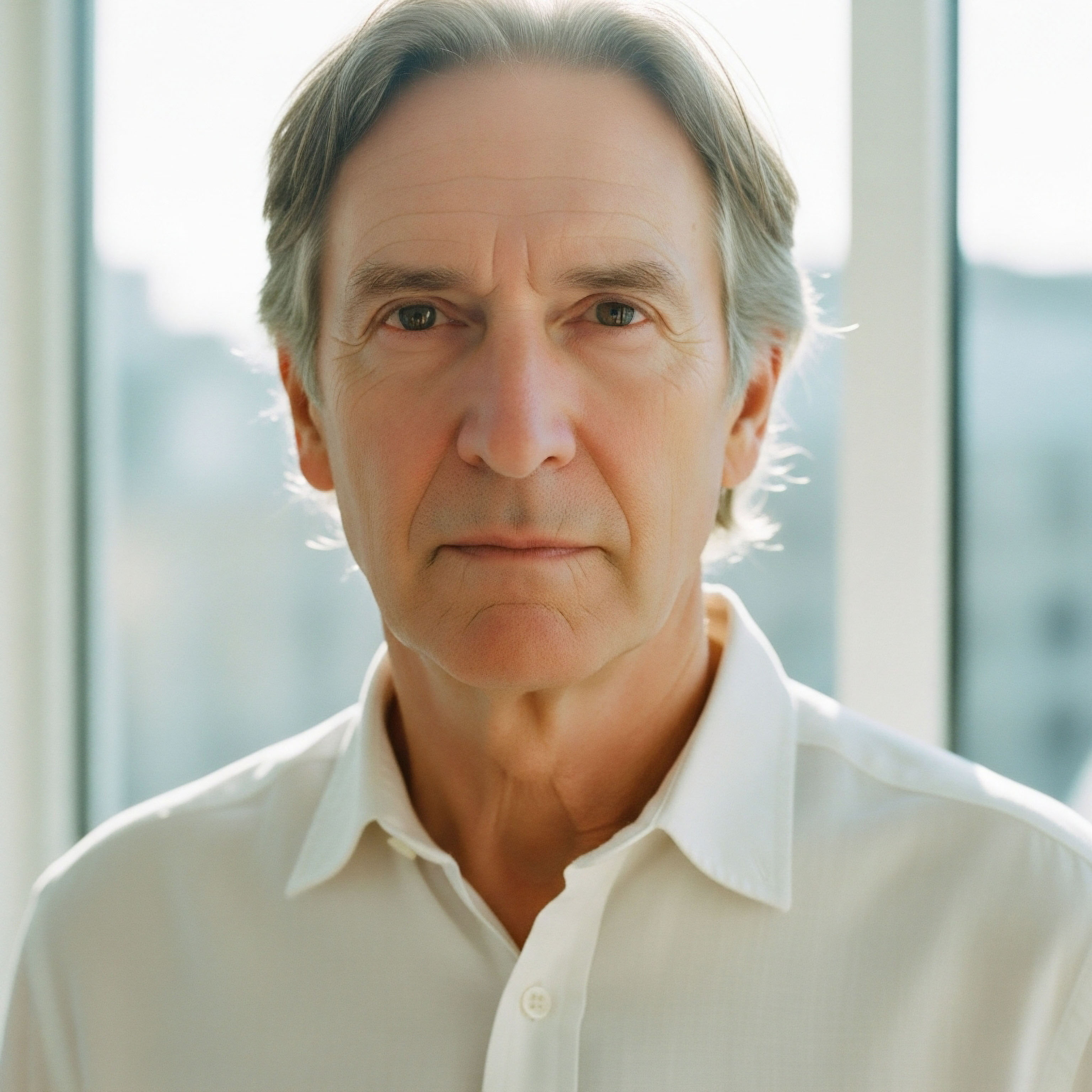

The term “medically supervised” is the most important component of this entire discussion. It signifies a therapeutic partnership between you and a clinician, grounded in a rigorous process of diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. This is not a casual undertaking. It begins with a comprehensive diagnostic workup.

A diagnosis of hypogonadism requires both the presence of consistent symptoms and signs, and unequivocally low serum testosterone concentrations, typically confirmed with at least two separate morning blood tests. This initial step is about establishing a clear clinical need, ensuring that the symptoms you are experiencing are directly linked to a verifiable hormonal deficiency.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, supervision involves creating a personalized protocol and then meticulously tracking its effects. This continuous oversight is what separates therapeutic intervention from misuse. It involves regular blood work to monitor not just testosterone levels, but a host of other critical biomarkers.

These tests ensure the dosage is correct and that the body is responding appropriately, allowing for adjustments to be made to prevent or manage potential side effects. This process is about steering the system, not just pressing an accelerator.

Medically supervised TRT is a precise clinical strategy to restore hormonal balance, guided by objective data and subjective well-being.

The Body’s Communication Network

Your endocrine system functions like a finely tuned orchestra, with the brain acting as the conductor. The process of testosterone production is governed by a feedback loop called the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The hypothalamus in the brain releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

LH then travels through the bloodstream to the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone. When testosterone levels are sufficient, they send a signal back to the brain to slow down GnRH and LH production, maintaining a state of balance.

When exogenous testosterone is introduced, the brain senses that levels are adequate and reduces its own signals (LH and FSH) to the testes. This is a natural and expected response. A well-designed TRT protocol anticipates this and may include adjunctive therapies to maintain the function of this axis. The goal of long-term therapy is to support the entire system, not just one component of it, ensuring that the body’s intricate communication network remains as functional as possible.

Intermediate

Advancing beyond the foundational concepts of testosterone’s role, a deeper analysis of long-term outcomes requires a granular look at the clinical protocols themselves. A properly managed TRT program is a dynamic process of biochemical recalibration. It involves a multi-faceted approach that uses specific medications to not only restore testosterone levels but also to manage the downstream effects of this restoration.

The long-term health profile of an individual on TRT is directly shaped by the intelligence and precision of their specific protocol.

The standard of care for male hormone optimization often involves more than just testosterone. A typical protocol is designed to mimic the body’s natural endocrine environment as closely as possible, addressing potential imbalances before they become clinical issues. This is achieved through a combination of therapeutic agents, each with a distinct purpose within the system.

Core Components of a Modern TRT Protocol

A comprehensive TRT protocol for men is built around several key components, each addressing a specific part of the endocrine feedback loop. The objective is to achieve stable testosterone levels while managing its conversion into other hormones and maintaining testicular function.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ This is a slow-acting injectable ester of testosterone, which forms the base of the therapy. Administered typically as a weekly or bi-weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injection, it provides a steady, predictable release of testosterone into the bloodstream. This stability is key to avoiding the wide hormonal fluctuations that can lead to side effects and a poor subjective response.

- Gonadorelin or hCG ∞ When external testosterone is administered, the brain’s production of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) decreases, which can lead to testicular atrophy and a shutdown of endogenous testosterone production. Gonadorelin, a GnRH analogue, or Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG), an LH analogue, is used to directly stimulate the testes. This maintains their size and function, preserving a degree of natural production and supporting fertility.

- Anastrozole ∞ Testosterone can be converted into estrogen via an enzyme called aromatase. While some estrogen is necessary for male health (supporting bone density, cognitive function, and libido), excessive levels can lead to side effects like gynecomastia (breast tissue development), water retention, and mood changes. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that blocks this conversion, allowing a clinician to carefully manage and balance the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. Its use is based on lab results and symptoms, not administered universally.

Monitoring the System Long-Term Health Markers

The safety and success of long-term TRT are contingent upon diligent monitoring. Regular blood tests provide the objective data needed to make informed adjustments to the protocol. These panels go far beyond a simple testosterone check.

Consistent monitoring of a full biomarker panel is the mechanism that ensures long-term safety and efficacy in hormonal therapy.

Key markers provide a window into how the body is adapting to the therapy. This data, combined with a patient’s subjective reports, allows for a highly personalized and responsive treatment plan. The table below outlines some of the primary biomarkers monitored during therapy and the rationale for their inclusion.

| Biomarker | Clinical Significance and Monitoring Rationale |

|---|---|

| Total and Free Testosterone |

This confirms the therapy is achieving its primary goal. Levels are typically targeted for the mid-to-upper end of the normal reference range to alleviate symptoms of hypogonadism effectively. |

| Estradiol (E2) |

Monitored to manage the aromatization of testosterone. Levels that are too high or too low can cause side effects. Anastrozole dosage is adjusted based on these readings in conjunction with patient symptoms. |

| Hematocrit and Hemoglobin |

Testosterone stimulates the production of red blood cells. An excessive increase, a condition called erythrocytosis, can thicken the blood and potentially increase the risk of thromboembolic events. Guidelines suggest that a hematocrit level above 54% requires intervention, such as a dose reduction or therapeutic phlebotomy. |

| Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) |

Historically, there were concerns that TRT could cause prostate cancer. Decades of research have not supported this. However, testosterone can stimulate the growth of existing prostate tissue. A rising PSA level prompts further urological evaluation to rule out underlying conditions. |

| Lipid Panel (HDL, LDL, Triglycerides) |

The effects of TRT on cholesterol can be variable. Monitoring lipid profiles ensures that the therapy is not adversely affecting cardiovascular risk factors. In many cases, by improving body composition and insulin sensitivity, TRT can lead to improvements in lipid profiles. |

What Are the Long Term Cardiovascular Outcomes?

The relationship between TRT and cardiovascular health has been a subject of intense study and some controversy. Early reports from flawed observational studies created concern. However, a large body of more recent and robust evidence, including meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, has not shown an increase in cardiovascular risk when TRT is properly administered to men with diagnosed hypogonadism.

In fact, some evidence suggests a potential benefit. Low testosterone itself is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. By improving factors like muscle mass, reducing visceral fat, and improving insulin sensitivity, TRT may help mitigate overall cardiovascular risk. The key is appropriate patient selection and vigilant monitoring to manage factors like erythrocytosis.

Academic

A sophisticated evaluation of the long-term sequelae of testosterone therapy demands a departure from broad strokes and a focused examination of specific physiological systems. The interaction between exogenous testosterone administration and the hematopoietic system, specifically the development of erythrocytosis, provides a compelling case study.

This common side effect is not merely a number on a lab report; it is a window into the complex interplay between androgens, iron metabolism, and renal signaling. Understanding its mechanism is central to appreciating the risk-management strategies inherent in modern endocrinological practice.

The Pathophysiology of Testosterone-Induced Erythrocytosis

Testosterone-induced erythrocytosis is defined as a rise in hematocrit (Hct), the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood, to levels exceeding the normal physiological range, typically cited as >52-54%. This phenomenon is one of the most frequently observed adverse events in clinical trials of TRT. The mechanism is not singular but appears to be driven by at least two primary pathways.

First, testosterone directly stimulates the kidneys to produce erythropoietin (EPO), the primary hormone that signals the bone marrow to increase red blood cell production. Second, and perhaps more subtly, testosterone appears to alter iron metabolism. It does this by suppressing the production of hepcidin, a liver-produced peptide that acts as the master regulator of iron availability.

Lower hepcidin levels lead to increased iron absorption from the gut and greater mobilization of iron from stores, making more of this essential component available for the synthesis of hemoglobin within new red blood cells. The combined effect of increased EPO signaling and enhanced iron availability creates a potent stimulus for erythropoiesis. The formulation of testosterone administered also plays a role, with injectable forms causing more significant supraphysiological peaks and thus a higher incidence of erythrocytosis compared to transdermal preparations.

Prostate Health a Paradigm Shift in Understanding

The historical apprehension regarding TRT and prostate cancer risk was rooted in a simplistic model of androgen-dependent growth. The work of Huggins and Hodges in the 1940s demonstrated that castration caused prostate cancer to regress, leading to the logical, yet ultimately incomplete, conclusion that restoring testosterone would promote its growth. This gave rise to the “Androgen Hypothesis.”

Decades of subsequent research have led to the development of the Prostate Saturation Model. This model posits that the androgen receptors within the prostate can become fully saturated at relatively low levels of testosterone. Once these receptors are saturated, providing additional testosterone does not produce a further growth-stimulating effect.

This explains why men with low testosterone see a small initial rise in PSA when starting therapy as their levels move into the normal range, but why further increases do not occur as levels are maintained.

Numerous large-scale studies and meta-analyses have failed to show that TRT increases the risk of developing prostate cancer in men with no prior history of the disease. Clinical guidelines from The Endocrine Society and the American Urological Association reflect this modern understanding, stating there is no evidence linking TRT to prostate cancer development.

The focus of monitoring with PSA is to detect any pre-existing, undiagnosed cancer that might be stimulated, not to screen for new cancers caused by the therapy.

The evolution of the prostate saturation model has fundamentally reframed the clinical conversation around testosterone therapy and prostate safety.

The table below contrasts the outdated androgen hypothesis with the current saturation model, highlighting the key distinctions that inform contemporary clinical practice.

| Concept | Outdated Androgen Hypothesis | Modern Prostate Saturation Model |

|---|---|---|

| Dose-Response |

Assumed a linear relationship ∞ more testosterone equals more prostate growth indefinitely. |

Proposes a saturation point; once androgen receptors are saturated, additional testosterone has minimal further effect on growth. |

| Clinical Implication |

Led to the belief that TRT was highly risky for the prostate and absolutely contraindicated in men with any history of prostate issues. |

Explains why TRT is considered safe regarding de novo cancer risk and can be considered cautiously in select men treated for prostate cancer. |

| PSA Monitoring |

A rise in PSA was interpreted as a sign of therapy-induced danger. |

An initial small rise is expected as levels normalize. Subsequent stability is the norm. A continued rise prompts investigation for an underlying condition. |

Metabolic and Musculoskeletal Systemic Effects

Beyond the specific concerns of erythrocytosis and prostate health, the long-term impact of TRT extends to systemic metabolic and musculoskeletal benefits. Low testosterone is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. By improving body composition ∞ specifically by increasing lean muscle mass and reducing visceral adipose tissue ∞ TRT can directly improve insulin sensitivity. Muscle is a primary site of glucose disposal, and increasing muscle mass enhances the body’s ability to manage blood sugar.

Furthermore, testosterone plays a direct role in maintaining bone mineral density. It does so both directly, by acting on osteoblasts (bone-building cells), and indirectly, through its aromatization to estrogen, which is also critical for bone health. In men with confirmed hypogonadism, long-term TRT has been shown to increase bone mineral density, particularly in the lumbar spine and hip, reducing the long-term risk of osteoporotic fractures.

References

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715 ∞ 1744.

- Corona, Giovanni, et al. “Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Cardiovascular Risk ∞ A Review.” World Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 33, no. 3, 2015, pp. 130-142.

- Khera, Mohit. “Testosterone Replacement and Prostate Cancer.” Current Opinion in Urology, vol. 26, no. 2, 2016, pp. 139-143.

- Jones, S. D. et al. “Erythrocytosis Following Testosterone Therapy.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 22, no. 3, 2015, pp. 183-191.

- Wallis, Christopher J.D. et al. “Testosterone Replacement Therapy and the Risk of Favorable and Aggressive Prostate Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 35, no. 8, 2017, pp. 849-855.

- Muraleedharan, V. et al. “Testosterone Deficiency Is Associated with Increased Risk of Mortality and Testosterone Replacement Improves Survival in Men with Type 2 Diabetes.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 169, no. 6, 2013, pp. 725-733.

- Calof, O. M. et al. “Adverse Events Associated With Testosterone Replacement in Middle-Aged and Older Men ∞ A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials.” The Journals of Gerontology ∞ Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, vol. 60, no. 11, 2005, pp. 1451-1457.

- Saad, Farid, et al. “Long-Term Treatment of Hypogonadal Men with Testosterone Produces Substantial and Sustained Weight Loss.” Obesity, vol. 20, no. 10, 2012, pp. 1975-1981.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map of the complex biological territory associated with hormonal health. It details the known pathways, the monitored checkpoints, and the long-term destinations observed in clinical science. This map, however, is not the journey itself. Your personal health story, your symptoms, and your goals are what set the course. The data and protocols are tools for navigation, designed to be used within a collaborative partnership with a knowledgeable clinician.

Understanding the mechanics of TRT ∞ from the HPG axis to the saturation model of the prostate ∞ is the first step toward making informed decisions. It transforms the conversation from one of uncertainty to one of proactive management.

The ultimate aim is not simply to adjust a number on a lab report, but to restore a level of function and well-being that allows you to operate at your full potential. This knowledge equips you to ask precise questions, understand the answers, and actively participate in the stewardship of your own health.