Fundamentals

The question of starting a family often arrives with a weight of considerations, and when you are also managing your own health, those considerations can feel magnified. You may be navigating symptoms of low testosterone ∞ the fatigue, the mental fog, the loss of vitality ∞ and seeking a path back to function.

The decision to explore hormonal therapy is a significant step toward reclaiming your well-being. It is also a moment where concerns about future fertility rightfully come to the forefront. Understanding how these therapies interact with your body’s intricate systems is the first step in making informed choices that align with both your immediate health goals and your long-term life plans.

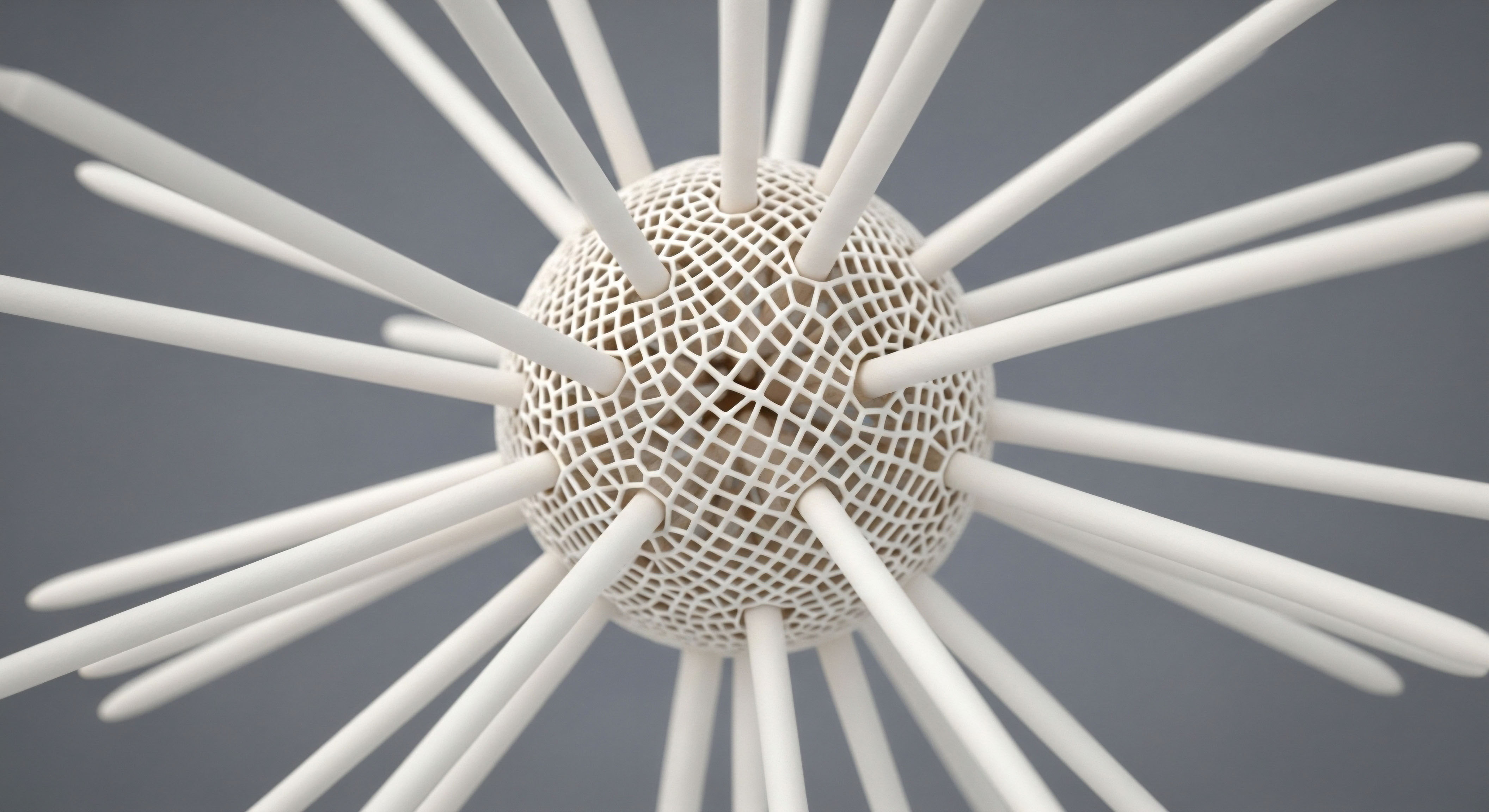

Your body operates on a system of elegant, internal communication. At the center of male hormonal health and fertility is a biological conversation known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as a command-and-control structure. The hypothalamus, a region in your brain, acts as the mission commander.

It sends out a signal called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This signal travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the field officer, instructing it to release two critical hormones into the bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These are the messengers sent to the operational base ∞ the testes.

Within the testes, LH and FSH have distinct, vital assignments. LH stimulates a specific group of cells, the Leydig cells, with one primary directive ∞ produce testosterone. This testosterone is responsible for the masculine characteristics you are familiar with, and it is also a key regulator of energy, mood, and metabolic health.

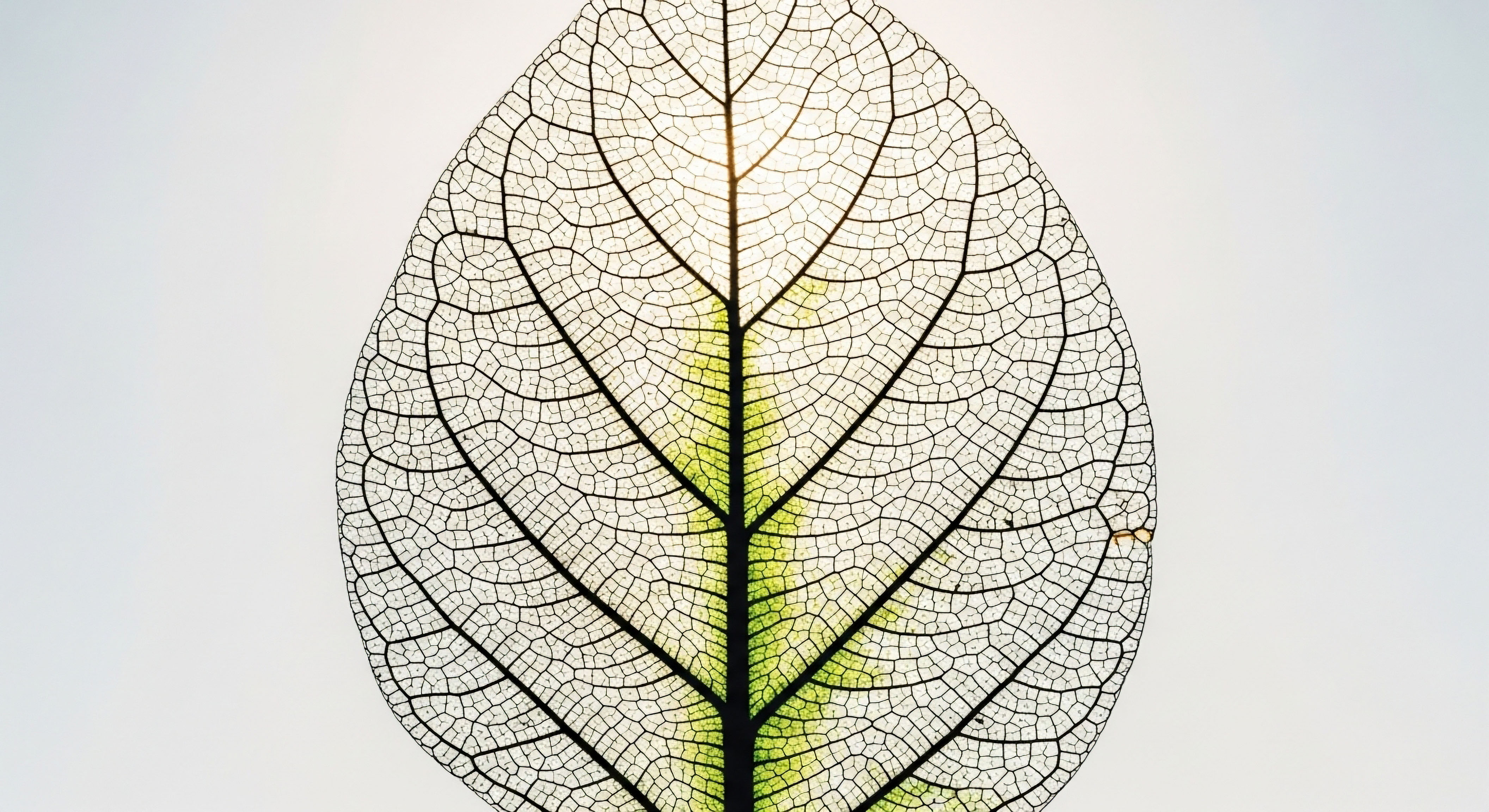

Simultaneously, FSH communicates with another set of cells, the Sertoli cells, which are the architects of sperm production, a process called spermatogenesis. For spermatogenesis to occur efficiently, the Sertoli cells require both the signal from FSH and a very high concentration of testosterone produced locally by the Leydig cells. This entire system is self-regulating; when testosterone levels in the blood are sufficient, the hypothalamus and pituitary slow down their signals, preventing overproduction. It is a finely tuned biological thermostat.

The Impact of Testosterone Therapy on the System

When you introduce testosterone from an external source, as in Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), your body detects its presence. The HPG axis, sensing that testosterone levels are adequate, powers down its own production line. The hypothalamus reduces its GnRH signal, which in turn causes the pituitary to stop releasing LH and FSH.

This shutdown has two direct consequences for the testes. Without the LH signal, the Leydig cells cease their testosterone production. Without the FSH signal and the high local testosterone levels, the Sertoli cells halt spermatogenesis. This is why TRT, while effective for treating symptoms of low testosterone, can lead to testicular atrophy and infertility. The operational base becomes dormant because the command center has gone quiet.

How Does HCG Restore the Connection?

This is where Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) provides a unique biological solution. HCG is a hormone that is structurally very similar to LH. Its molecular shape allows it to bind to and activate the same LH receptors on the Leydig cells in the testes.

In essence, hCG acts as a direct messenger, bypassing the silent hypothalamus and pituitary to deliver the “produce testosterone” command straight to the testes. By stimulating the Leydig cells, hCG prompts them to generate testosterone locally. This intratesticular testosterone is critical for maintaining testicular size and, most importantly, for providing the necessary fuel for the Sertoli cells to continue or restart the process of spermatogenesis. It effectively keeps the operational base online, even when the primary command chain is interrupted.

By mimicking the body’s natural Luteinizing Hormone, hCG directly stimulates the testes to produce testosterone, thereby maintaining the essential environment for sperm production.

Using hCG is a way to work with your body’s existing framework. It does not fix the upstream signaling from the brain. Instead, it provides the specific downstream signal that the testes need to remain active and functional. This approach allows for the management of hypogonadal symptoms while preserving the potential for fertility, a consideration of profound importance for many men on their health journey.

Intermediate

Advancing from the foundational principles of the HPG axis, we can now examine the clinical application of hCG with greater precision. The decision to use hCG is guided by a man’s specific circumstances, primarily his current hormonal status, his use of testosterone therapy, and his timeline for wanting to have children.

The protocols are designed to leverage hCG’s LH-mimicking action to achieve specific physiological outcomes, either as a standalone therapy or as an adjunct to a broader hormonal optimization plan.

HCG Monotherapy a Protocol for Fertility Initiation

For men diagnosed with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism ∞ a condition where the testes are healthy but the pituitary fails to send adequate LH and FSH signals ∞ hCG can be used as a primary treatment. This is often the case for men who have not started TRT but present with low testosterone and infertility. The objective of hCG monotherapy is to directly activate the testes to produce both testosterone and sperm, effectively replacing the missing LH signal from the pituitary.

A typical protocol involves subcutaneous injections of hCG, with dosages varying based on individual response. A common starting point might be 1,500 to 3,000 IU administered two to three times per week. The clinical goal is twofold ∞ first, to raise serum testosterone levels into a healthy physiological range to alleviate the symptoms of hypogonadism, and second, to initiate or restore spermatogenesis.

Progress is monitored through regular blood work, tracking levels of total and free testosterone, as well as estradiol, since hCG-stimulated testosterone production can also lead to an increase in estrogen conversion. Semen analysis is performed periodically, typically every two to three months, to quantify the response in sperm count, motility, and morphology. For many men with this condition, hCG monotherapy can successfully restore fertility over a period of several months to more than a year.

Adjunctive HCG Therapy Preserving Fertility during TRT

For men who require TRT to manage their symptoms but also wish to preserve their fertility, hCG is used as an adjunctive therapy. The logic here is preventative. By co-administering hCG alongside testosterone, the therapy aims to keep the testes functional from the outset, preventing the testicular shutdown that TRT would otherwise cause.

Research has shown that low-dose hCG is remarkably effective at this. While TRT alone can cause intratesticular testosterone to drop by over 90%, adding a small dose of hCG can maintain those levels, preserving the necessary environment for spermatogenesis.

The dosages for this purpose are generally lower than in monotherapy. A standard protocol might involve 250 to 500 IU of hCG injected subcutaneously two to three times per week. This is often sufficient to maintain testicular volume and sperm production in a majority of men on TRT. This approach offers a way to manage the symptoms of low testosterone without forcing a man to choose between his well-being and his future family planning goals.

Used alongside TRT, low-dose hCG acts as a maintenance signal to the testes, preventing the suppression of sperm production that would otherwise occur.

Comparing HCG Treatment Protocols

The choice between monotherapy and adjunctive therapy depends entirely on the individual’s clinical picture and personal goals. The following table outlines the key distinctions between these two common approaches.

| Parameter | HCG Monotherapy | HCG as Adjunct to TRT |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Candidate |

Men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, not currently on TRT, seeking to initiate fertility. |

Men on TRT seeking to preserve fertility and prevent testicular atrophy. |

| Therapeutic Goal |

To stimulate testosterone production and initiate spermatogenesis. |

To maintain intratesticular testosterone and ongoing spermatogenesis. |

| Typical Dosage Range |

1,500 – 3,000 IU, 2-3 times per week. |

250 – 500 IU, 2-3 times per week. |

| Effect on HPG Axis |

Bypasses a dysfunctional hypothalamus/pituitary to stimulate the testes directly. |

Bypasses the TRT-suppressed hypothalamus/pituitary to stimulate the testes directly. |

| Monitoring |

Serum testosterone, estradiol, and periodic semen analysis. |

Serum testosterone, estradiol, and baseline/periodic semen analysis if conception is actively sought. |

What Are the Limitations of HCG for Fertility?

It is important to recognize that hCG primarily replaces the LH signal. It does not replace the FSH signal. While the high levels of intratesticular testosterone stimulated by hCG are often sufficient to support spermatogenesis, some men, particularly those with severe or long-standing hypogonadism, may not achieve optimal sperm production with hCG alone.

The FSH signal, which directly targets the Sertoli cells, is also a component of robust sperm maturation. In cases where semen analysis shows an insufficient response to hCG, a clinician may consider adding a source of FSH, such as Human Menopausal Gonadotropin (hMG) or recombinant FSH (rFSH), to the protocol. This dual-gonadotropin approach more closely mimics the body’s natural signaling process and can be more effective for inducing spermatogenesis in difficult cases.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of long-term fertility outcomes with Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) requires moving beyond its role as a simple Luteinizing Hormone (LH) analogue. We must examine the subtle yet significant differences in its biochemical action, its sustained impact on Leydig cell function, and the complex interplay between gonadotropin activity and the full process of spermatogenesis.

The long-term efficacy of hCG is fundamentally tied to its ability to maintain a state of readiness within the testicular microenvironment, a state that can be compromised by both exogenous testosterone and the very nature of hCG’s supraphysiological signaling.

Molecular Action and Leydig Cell Dynamics

Natural LH is secreted from the pituitary gland in a pulsatile fashion, with bursts occurring every 90-120 minutes. This rhythmic signaling allows for periods of Leydig cell stimulation followed by periods of rest, preventing receptor downregulation and desensitization. HCG, in contrast, has a much longer biological half-life, approximately 24-36 hours compared to LH’s 20-60 minutes.

This results in a continuous, non-pulsatile stimulation of the LH receptor. While this tonic stimulation is effective at producing high levels of intratesticular testosterone, long-term, high-dose administration carries a theoretical risk of Leydig cell desensitization. This phenomenon involves the internalization of LH receptors from the cell surface and a decoupling of the receptor from its intracellular signaling cascade, potentially reducing testosterone output over time.

Clinical practice has adapted to this reality. The use of lower, more frequent doses of hCG (e.g. 250-500 IU every other day) when used adjunctively with TRT is a strategy designed to mitigate this risk. This approach aims to provide enough stimulation to maintain intratesticular testosterone without overwhelming the Leydig cells, preserving their responsiveness for long-term use.

Studies focusing on men using hCG to maintain fertility while on TRT have demonstrated sustained preservation of spermatogenesis over periods exceeding one year, suggesting that these lower-dose protocols are effective at balancing stimulation with sustainability.

The Two Pillars of Spermatogenesis FSH and Intratesticular Testosterone

Successful spermatogenesis depends on two synergistic hormonal inputs to the testes ∞ FSH acting on Sertoli cells and high concentrations of intratesticular testosterone produced by Leydig cells. HCG therapy directly addresses only the latter. It has no intrinsic FSH-like activity.

The initiation of spermatogenesis in men with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism often requires a dual approach from the start, using both hCG to stimulate testosterone and an FSH-containing product (like hMG or rFSH) to mature the Sertoli cells and drive sperm production.

In the context of reversing TRT-induced azoospermia, the situation is different. The Sertoli cells in these men were previously functional. For many, restoring high levels of intratesticular testosterone with hCG monotherapy is sufficient to restart spermatogenesis. The recovery timeline, however, can be variable.

Studies have shown that the median time for sperm to reappear in the ejaculate can be around 3 to 6 months, but a full recovery to pre-TRT baseline or to levels sufficient for conception can take 12 to 24 months for some individuals. The duration of prior testosterone use appears to be a factor influencing the speed of recovery.

The long-term success of hCG in fertility preservation hinges on its ability to maintain high local testosterone levels without inducing significant Leydig cell desensitization.

The following table summarizes data from key research areas, illustrating the outcomes under different clinical scenarios.

| Clinical Scenario | Typical Protocol | Observed Long-Term Outcome | Key Scientific Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism |

hCG (1500-2000 IU 2x/week) + hMG/rFSH (75-150 IU 3x/week) |

High rates of spermatogenesis induction, but may require continuous, long-term treatment to maintain fertility. |

Requires both LH and FSH receptor stimulation to initiate puberty and spermatogenesis in a naive testis. |

| Preservation during TRT |

Testosterone + hCG (500 IU every other day) |

Spermatogenesis is preserved in a majority of men, with stable intratesticular testosterone levels observed at one year. |

Low-dose hCG prevents testicular quiescence and maintains the intratesticular environment needed for ongoing sperm production. |

| Restoration after TRT |

hCG (3000 IU every other day) +/- Clomiphene Citrate |

Sperm recovery in most men, with median time to recovery of 3-6 months. Time to conception can be longer. |

Success depends on restarting a previously functional system. FSH levels may remain suppressed by high-dose hCG, sometimes necessitating the addition of rFSH. |

What Is the Enduring Impact on Testicular Function?

A critical question is whether long-term hCG use has any permanent effect on testicular function after its cessation. Current evidence does not suggest a permanent impairment. The testes appear to retain their ability to respond to the body’s native LH and FSH once the HPG axis recovers.

For a man on TRT and adjunctive hCG, discontinuing both therapies will initiate a recovery period. The HPG axis will slowly come back online, and the testes, having been kept active by hCG, are positioned to respond to the returning native LH and FSH signals. The timeline for this recovery varies greatly among individuals.

For a man using hCG monotherapy, cessation would mean returning to his baseline state of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. The long-term utility of hCG is therefore not as a “cure,” but as a functional replacement for a missing hormonal signal, effective for as long as it is administered.

References

- Ramasamy, Ranjith, et al. “Preserving fertility in the hypogonadal patient ∞ an update.” Translational Andrology and Urology, vol. 4, no. 2, 2015, pp. 125-130.

- Hsieh, Tung-Chin, et al. “Concomitant human chorionic gonadotropin preserves spermatogenesis in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy.” The Journal of Urology, vol. 189, no. 2, 2013, pp. 647-650.

- Wenker, Evan P. et al. “The Use of HCG-Based Combination Therapy for Recovery of Spermatogenesis after Testosterone Use.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 12, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1334-1340.

- Butler, Christopher A. et al. “Indications for the use of human chorionic gonadotropic hormone for the management of infertility in hypogonadal men.” Translational Andrology and Urology, vol. 8, no. 4, 2019, S368-S375.

- Bouloux, Pierre-Marc G. et al. “Induction of spermatogenesis by recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone (Gonal-F) in hypogonadotropic hypogonadal men.” Human Reproduction, vol. 17, no. 4, 2002, pp. 894-901.

- Vicari, E. et al. “Testicular volume and serum inhibin B levels as the best predictors of circulating gonadotropins in male patients with idiopathic and post-traumatic spinal cord injury.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 27, no. 10, 2004, pp. 908-915.

- Kim, Edmund D. et al. “The restoration of spermatogenesis in men with testosterone-induced azoospermia.” The Journal of Urology, vol. 153, no. 5, 1995, pp. 1741-1743.

- Habous, M. et al. “Clomiphene citrate and human chorionic gonadotropin are both effective in treating secondary hypogonadism in obese men.” BJU International, vol. 122, no. 5, 2018, pp. 889-897.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological pathways and clinical strategies related to hCG and male fertility. This map details the terrain, highlights the known routes, and marks areas of complexity. Your personal health, however, is the unique territory to which this map applies.

The data points, the protocols, and the physiological explanations are the tools for navigation. The true work begins when you overlay this knowledge onto your own lived experience, your symptoms, your lab results, and your personal definition of a fulfilling life.

Understanding the mechanics of the HPG axis or the half-life of a hormone is a powerful act of self-awareness. It transforms abstract feelings of being unwell into concrete, understandable processes within your own body. This knowledge shifts the dynamic.

You become an active participant in your own care, capable of engaging in substantive conversations with your clinical team. The path forward is one of measurement, adjustment, and recalibration, always with your specific goals in view. Your biology is not a fixed state; it is a dynamic system. The journey toward hormonal balance and well-being is a process of learning its language and guiding it back toward its optimal function.