Fundamentals

You may feel it as a subtle shift in your energy in the afternoon, a change in your sleep patterns, or a frustrating plateau in your fitness goals. It is a common experience to attribute these feelings to the inevitable process of aging or the daily grind of a demanding life.

Yet, the answer might be found within the intricate communication network of your body, the endocrine system, and its complex relationship with a regular habit ∞ a glass of wine with dinner, a beer after work. This exploration is a personal one, a journey into understanding how your own biological systems respond to alcohol, empowering you to reclaim vitality and function without compromise.

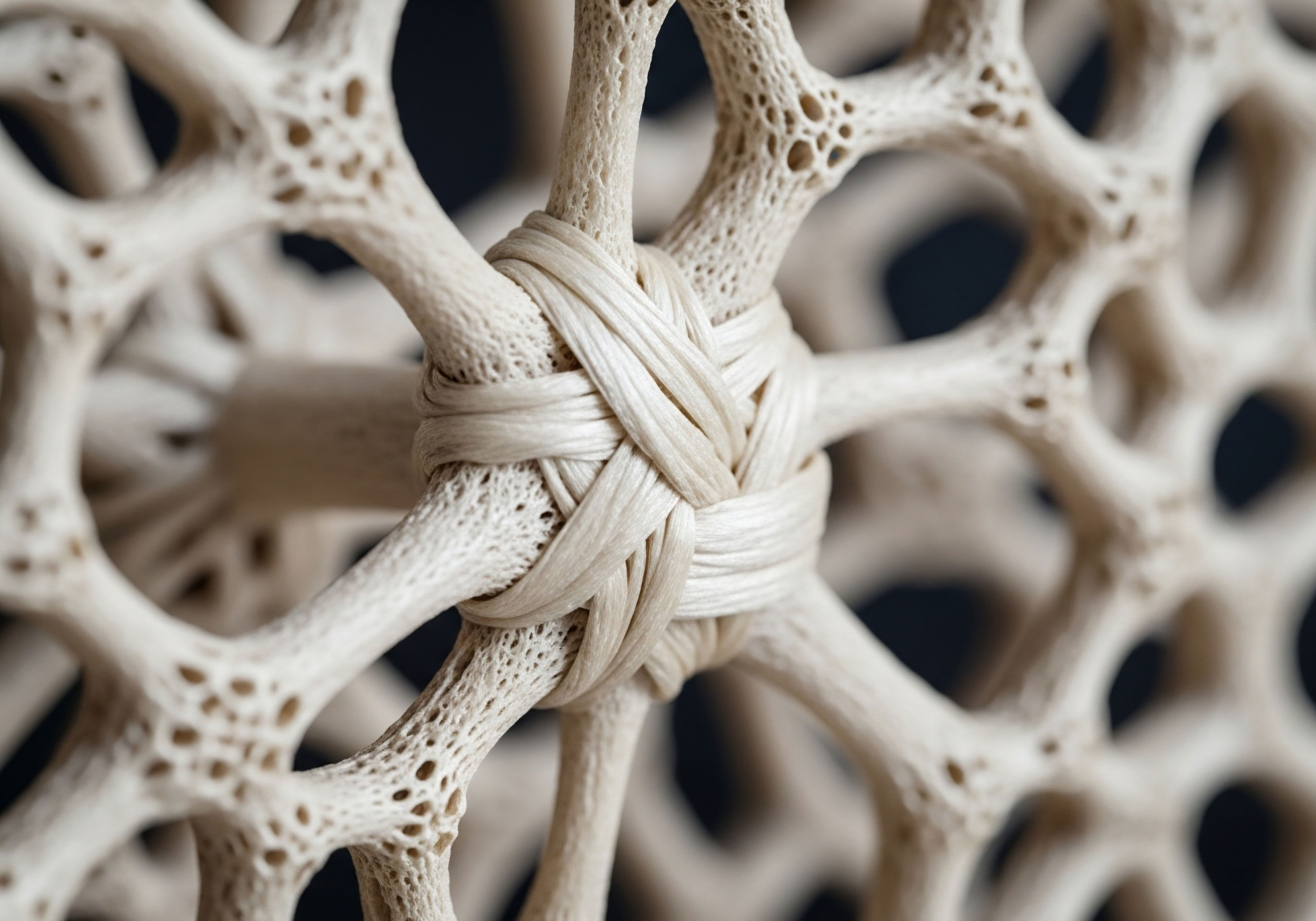

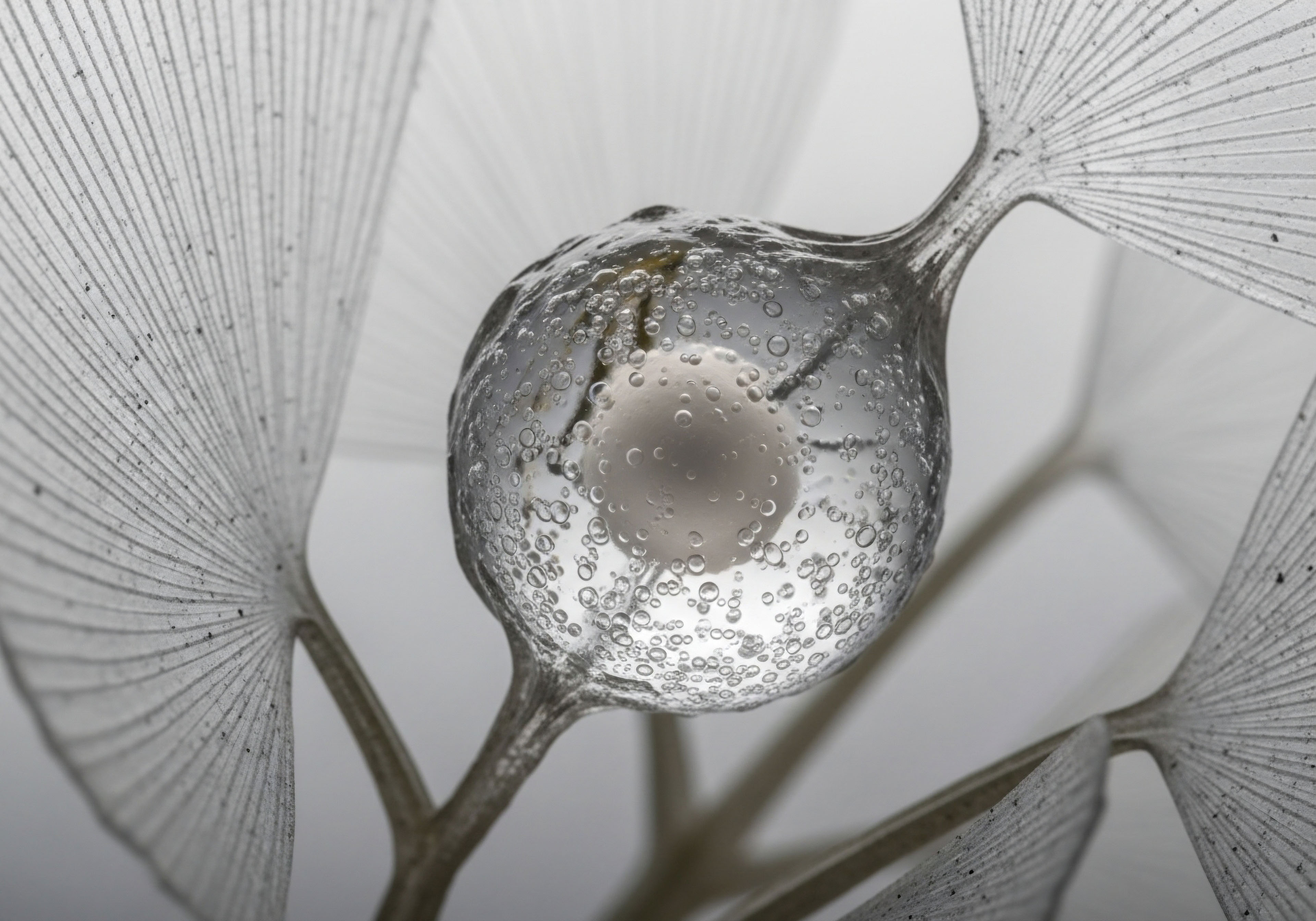

The endocrine system functions as the body’s internal messaging service, a sophisticated network of glands that produce and secrete hormones. These chemical messengers travel through the bloodstream, regulating everything from your metabolism and mood to your sleep cycles and reproductive health.

Think of it as a finely tuned orchestra, where each hormone is an instrument playing a specific part in a grand, biological symphony. When this system is balanced, the result is a state of well-being, energy, and resilience. The introduction of a substance like alcohol, even in moderation, acts as a persistent source of biochemical noise, subtly interfering with the clarity of these hormonal signals.

The Central Command and Its Lines of Communication

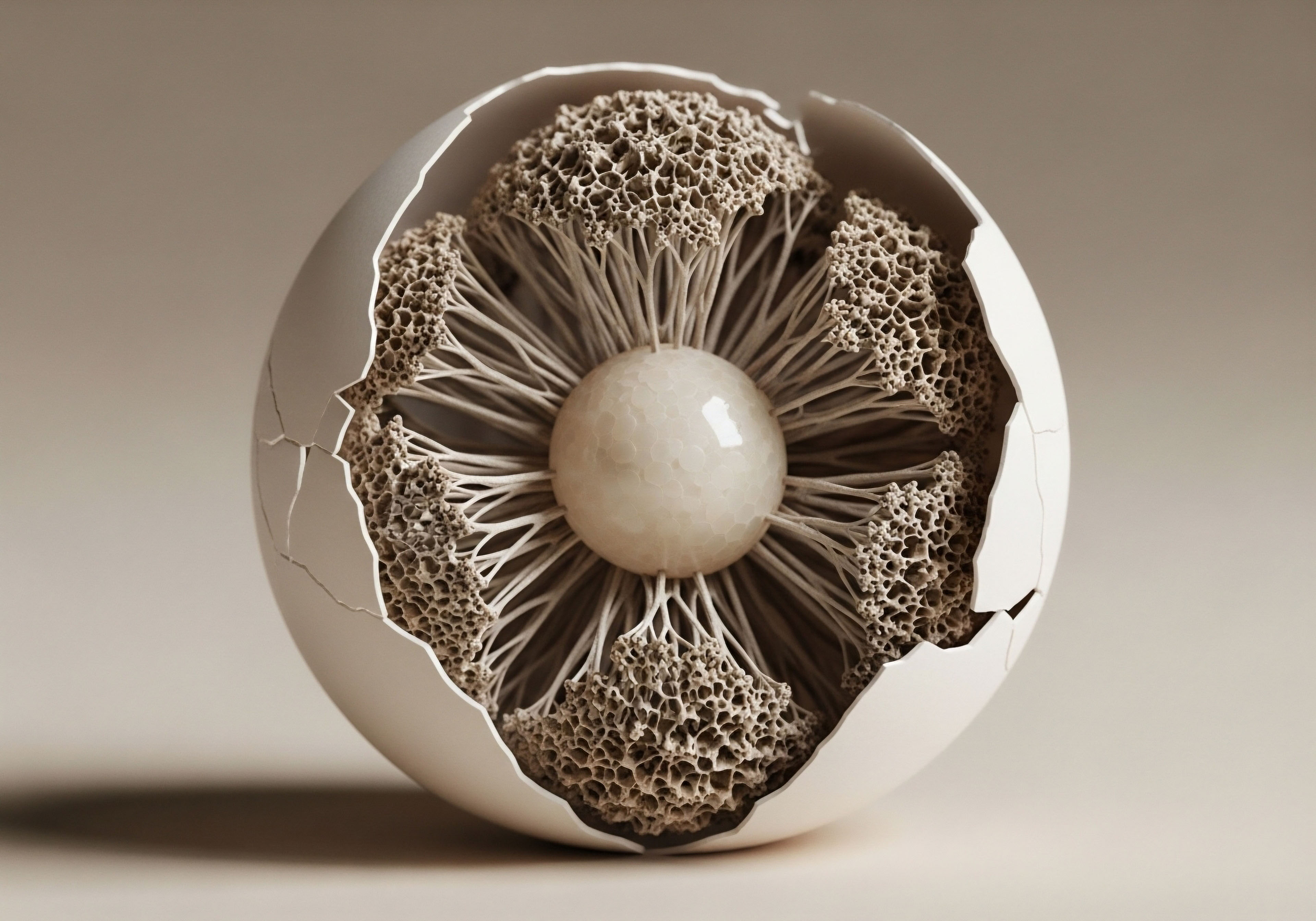

At the heart of your endocrine system are the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, located in the brain. This duo acts as the central command, assessing your body’s status and sending out hormonal directives to other glands. The primary communication channels they oversee are called axes, the most relevant to this discussion being the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs your stress response, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which manages reproductive function.

When you consume alcohol, it directly influences this central command. Ethanol crosses the blood-brain barrier with ease, altering the function of neurotransmitters that the hypothalamus relies on for information. This interference can lead to inappropriate signals being sent down the line.

For instance, alcohol can initially suppress the HPA axis, leading to a temporary feeling of relaxation. However, as the alcohol is metabolized, the system often rebounds, leading to an over-activation of the stress response, which can disrupt sleep and increase feelings of anxiety hours later. This is a classic example of alcohol’s disruptive echo in your hormonal environment.

Moderate alcohol consumption introduces a disruptive signal into the body’s finely tuned hormonal communication network, affecting metabolism, stress, and reproductive health.

How Does Alcohol Disrupt Hormonal Balance in Men?

In men, the HPG axis is responsible for the production of testosterone, a key hormone for maintaining muscle mass, bone density, libido, and overall vitality. Alcohol consumption can interfere with this axis at multiple levels. It can dampen the signaling from the pituitary gland (luteinizing hormone, or LH), which tells the testes to produce testosterone.

Furthermore, the metabolic process of breaking down alcohol in the liver can generate oxidative stress, a state of cellular damage that directly impairs the function of the Leydig cells in the testes where testosterone is synthesized.

Another critical effect is the increase in aromatase activity. Aromatase is an enzyme that converts testosterone into estrogen. Alcohol consumption, particularly when it contributes to increased body fat, can upregulate this enzyme. The result is a double-hit on male hormonal health ∞ lower testosterone production combined with an accelerated conversion of the remaining testosterone into estrogen.

This shift in the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio can contribute to symptoms like fatigue, reduced muscle mass, and increased abdominal fat, creating a cycle that further perpetuates hormonal imbalance.

How Does Alcohol Disrupt Hormonal Balance in Women?

In women, the HPG axis governs the menstrual cycle, ovulation, and the delicate interplay between estrogen and progesterone. Alcohol can disrupt the regular pulsatile release of hormones from the pituitary that orchestrates this cycle. This can lead to irregularities in the menstrual cycle, anovulatory cycles (where ovulation does not occur), and challenges with fertility.

For women in the perimenopausal transition, a time when the hormonal system is already in flux, alcohol can exacerbate symptoms like hot flashes and sleep disturbances. Acute alcohol consumption can cause a temporary spike in estradiol levels, potentially by impairing its metabolism in the liver. This sudden fluctuation can intensify the hormonal chaos that characterizes this life stage.

For post-menopausal women, particularly those on hormonal optimization protocols, the impact of alcohol on estrogen metabolism remains a significant consideration. The liver is the primary site for metabolizing both alcohol and hormones. When it is burdened with processing alcohol, its capacity to effectively clear and manage estrogen metabolites can be compromised.

This can influence the overall hormonal environment and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Understanding this interaction is a key part of creating a stable and supportive biochemical foundation for long-term health.

Intermediate

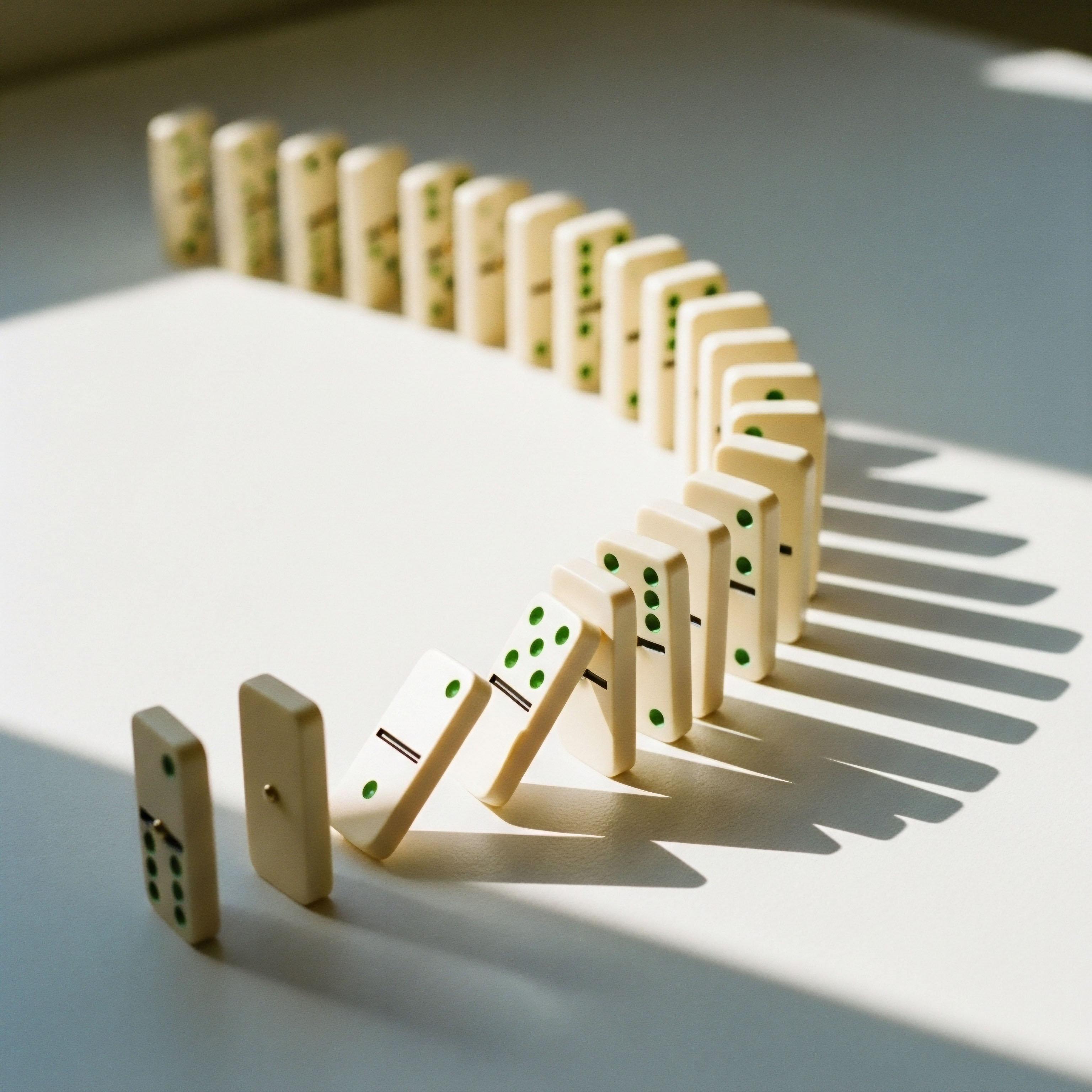

Moving beyond a foundational understanding, a deeper analysis reveals that moderate, long-term alcohol consumption functions as a chronic endocrine disruptor. It systematically degrades the efficiency of the body’s hormonal feedback loops. These loops are the elegant self-regulating mechanisms that maintain homeostasis.

A feedback loop works much like a thermostat in your home ∞ when a hormone level deviates from its set point, a signal is sent back to the central command (the hypothalamus and pituitary) to adjust production. Alcohol introduces static into these signaling pathways, making the system less responsive and less precise. This degradation is a key mechanism behind the wide-ranging symptoms that can manifest over time.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis under Siege

The HPA axis is your primary stress-response system. In a healthy state, it responds to a stressor by releasing cortisol, which mobilizes energy and enhances focus. Once the stressor is gone, a negative feedback signal from cortisol tells the hypothalamus and pituitary to stand down, and the system returns to baseline.

Chronic alcohol consumption fundamentally alters this dynamic. While an evening drink might initially feel relaxing by suppressing glutamatergic (excitatory) neurotransmission, the body initiates a compensatory rebound. It upregulates glutamate receptors to counteract the sedative effect. When the alcohol wears off several hours later, typically during the night, the nervous system is left in an over-excited state.

This leads to a surge in cortisol and norepinephrine at a time when they should be at their lowest, fragmenting sleep and preventing the deep, restorative phases necessary for physical and cognitive repair.

This repeated cycle of suppression and rebound ultimately dysregulates the HPA axis. The system can become blunted, less able to mount an effective cortisol response to genuine daytime stressors, leading to feelings of fatigue and burnout. Simultaneously, it becomes hyper-reactive during the night, contributing to chronic insomnia and anxiety. This state of HPA dysfunction is a significant contributor to the metabolic consequences of long-term alcohol use, as chronically elevated cortisol can promote insulin resistance and abdominal fat storage.

Table of HPA Axis Dysregulation

| Phase of Alcohol Exposure | Immediate Neurological Effect | Compensatory Rebound Effect (3-6 hours later) | Long-Term Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Consumption (0-2 hours) | Suppression of HPA axis; GABAergic (calming) effect enhanced. | N/A | Temporary feeling of relaxation. |

| Metabolic Clearance (2-8 hours) | Alcohol levels decline, removing the suppressive signal. | Hyper-excitable state due to upregulated glutamate; cortisol and norepinephrine surge. | Fragmented sleep, middle-of-the-night awakenings, anxiety. |

| Chronic Moderate Use (Months to Years) | Repeated cycles of suppression and rebound. | System adapts to the presence of alcohol. | Blunted daytime cortisol response (fatigue) and persistent nighttime hyper-activation (insomnia, anxiety, metabolic disruption). |

Implications for Hormonal Optimization Protocols

For individuals undertaking hormonal optimization, understanding alcohol’s impact is paramount for the success of the therapy. The presence of alcohol can directly counteract the goals of these sophisticated clinical protocols.

- Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in Men ∞ A standard TRT protocol, such as weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate, aims to restore testosterone to optimal levels. However, moderate alcohol consumption can undermine this in two ways. Firstly, it promotes the aromatization of the administered testosterone into estrogen, potentially requiring higher doses of an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to manage side effects. Secondly, the oxidative stress from alcohol metabolism can increase systemic inflammation, which can blunt the body’s sensitivity to androgens, meaning you get less “bang for your buck” from the therapy. The use of Gonadorelin to maintain natural testicular function can also be less effective if the Leydig cells are impaired by alcohol-induced oxidative stress.

- Hormone Therapy in Women ∞ For women on low-dose Testosterone Cypionate for libido and vitality, or on progesterone protocols to manage perimenopausal symptoms, alcohol’s disruption of liver metabolism is a primary concern. The liver must process both the therapeutic hormones and the alcohol. This competition can lead to inconsistent hormone levels and a less predictable response to therapy. The sleep disruption caused by alcohol’s HPA axis effects can also counteract the benefits of progesterone, which is often prescribed for its calming, pro-sleep effects.

- Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy ∞ Therapies using peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 are designed to stimulate the body’s natural production of growth hormone (GH), primarily during deep sleep. Since alcohol profoundly disrupts sleep architecture and suppresses the deep, slow-wave sleep stages where the majority of GH is released, it directly sabotages the efficacy of these protocols. An individual might be investing in peptide therapy while simultaneously cancelling out its primary mechanism of action with an evening drink.

Alcohol’s disruption of sleep architecture and liver metabolism directly undermines the efficacy of advanced hormonal therapies, including TRT and growth hormone peptides.

The Thyroid and Metabolic Rate

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis regulates your metabolism. The pituitary releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), which tells the thyroid gland to produce thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). T3 is the more active hormone that drives metabolic rate in cells throughout the body. Chronic alcohol consumption can suppress TSH release from the pituitary.

More significantly, it can impair the crucial conversion of T4 to the active T3 in the liver. The liver is a primary site for this conversion, and when its resources are diverted to detoxifying alcohol, thyroid function can become suboptimal.

This can manifest as symptoms of subclinical hypothyroidism ∞ persistent fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and cognitive sluggishness, even when standard TSH tests appear to be within the normal range. This illustrates how alcohol can create a functional hormonal deficiency without necessarily altering the most commonly tested lab markers.

Academic

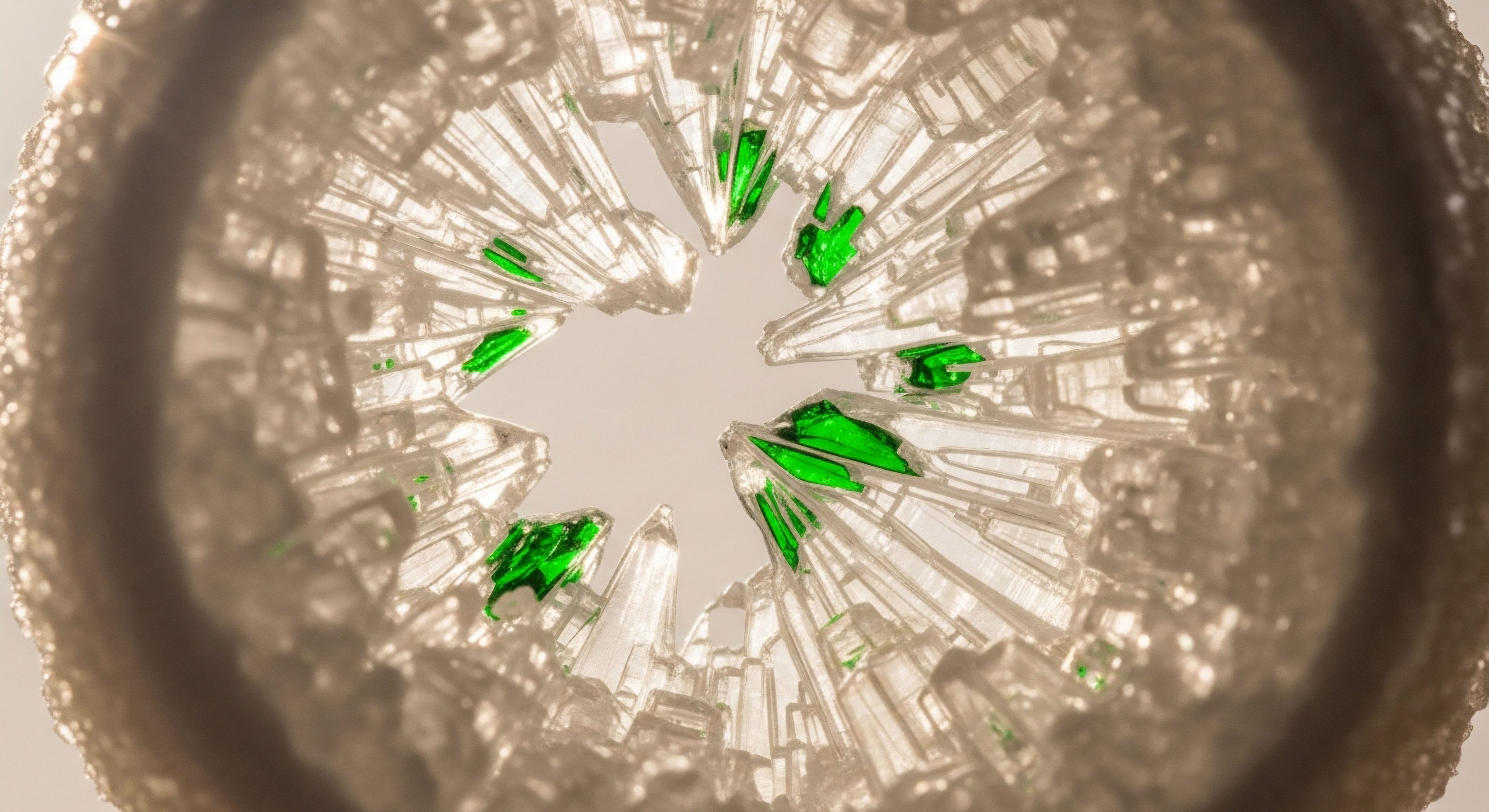

A granular, academic examination of alcohol’s endocrine effects requires moving beyond systemic descriptions to the molecular level. The primary mechanism of damage is the generation of metabolic toxicity and oxidative stress, which institutes a cascade of deleterious changes in steroidogenesis, receptor sensitivity, and gene expression.

The metabolism of ethanol itself is the origin of this disruption. In the liver, the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) converts ethanol to acetaldehyde, a highly toxic and carcinogenic compound. Acetaldehyde is then converted to acetate by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). This process consumes the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), drastically altering the NAD+/NADH ratio within the cell. This single biochemical shift has profound downstream consequences for all metabolic and hormonal functions.

The Molecular Sabotage of Steroidogenesis

Steroidogenesis, the synthesis of all steroid hormones (including cortisol, testosterone, and estradiol), is a series of enzymatic reactions heavily dependent on a healthy intracellular environment. The altered NAD+/NADH ratio caused by alcohol metabolism directly inhibits key steps in this process.

- Inhibition of Pregnenolone Synthesis ∞ The very first, rate-limiting step of steroidogenesis is the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone by the enzyme P450scc (cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme) within the mitochondria. This process is highly sensitive to the cell’s redox state. The flood of NADH from alcohol metabolism creates a state of reductive stress within the mitochondria, impairing the efficiency of the electron transport chain and reducing the activity of P450scc. This creates a fundamental bottleneck in the production of all steroid hormones.

- Direct Acetaldehyde Toxicity ∞ Acetaldehyde is far more than a simple metabolic intermediate; it is a highly reactive molecule that forms adducts with proteins and DNA. In the testes and adrenal glands, acetaldehyde adducts can bind directly to steroidogenic enzymes, deforming their structure and inactivating them. This provides a direct chemical mechanism for the observed decrease in testosterone and cortisol production independent of the HPG or HPA axis signaling.

- Upregulation of Aromatase Gene Expression ∞ The link between alcohol and increased aromatase activity extends to the level of gene transcription. Inflammatory cytokines, whose levels are often elevated with chronic alcohol consumption, have been shown to upregulate the expression of the CYP19A1 gene, which codes for the aromatase enzyme. This means the body is instructed to build more of the machinery that converts testosterone to estrogen, a more permanent shift than a temporary enzymatic activation.

What Is the Impact on Hormonal Receptor Sensitivity?

Hormones exert their effects by binding to specific receptors on or inside target cells. The efficacy of a hormonal signal depends on both the concentration of the hormone and the number and sensitivity of these receptors. Long-term alcohol consumption degrades receptor function through several mechanisms rooted in oxidative stress.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as byproducts of both ethanol metabolism and the resulting mitochondrial dysfunction, damage cellular membranes through lipid peroxidation. Hormone receptors are proteins embedded within these membranes. Damage to the surrounding lipid structure can alter the receptor’s conformation, making it less able to bind to its corresponding hormone.

This can induce a state of hormone resistance. For example, even if circulating testosterone levels are statistically “normal,” if the androgen receptors in muscle and brain tissue are less sensitive due to oxidative damage, the individual will experience the functional symptoms of low testosterone. This explains the common clinical observation of symptomatic patients who present with lab values that are not alarmingly low but are clearly suboptimal for their individual physiology.

At a molecular level, alcohol metabolism generates toxic byproducts and oxidative stress that directly inhibit hormone synthesis and damage cellular receptors, creating a state of functional hormone resistance.

Table of Molecular Effects of Ethanol Metabolism on Endocrine Function

| Molecular Target | Mechanism of Disruption | Biochemical Consequence | Clinical Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial NAD+/NADH Ratio | Ethanol metabolism via ADH and ALDH consumes NAD+, increasing NADH. | Inhibition of NAD+-dependent enzymes; reductive stress. | Impaired gluconeogenesis, reduced fatty acid oxidation, bottleneck in steroidogenesis. |

| Steroidogenic Enzymes (e.g. P450scc) | Direct inhibition by acetaldehyde adducts; reduced efficiency due to reductive stress. | Decreased conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone; impaired testosterone synthesis. | Lowered testosterone, DHEA, and cortisol output; hypogonadism. |

| Hormone Receptors (e.g. Androgen Receptor) | Lipid peroxidation of cell membranes by ROS damages receptor structure. | Reduced binding affinity and signal transduction. | Functional hormone resistance; symptoms of deficiency despite “normal” lab values. |

| CYP19A1 Gene (Aromatase) | Upregulation by alcohol-induced inflammatory cytokines. | Increased synthesis of aromatase enzyme. | Higher conversion of testosterone to estradiol; altered T:E ratio. |

The Interplay with Peptide and Post-Cycle Therapies

The academic view clarifies why alcohol is particularly detrimental for individuals using advanced therapeutic protocols. For a man on a Post-TRT or Fertility-Stimulating Protocol involving agents like Gonadorelin, Tamoxifen, or Clomid, the goal is to restart the endogenous HPG axis. These drugs work by stimulating the pituitary (Clomid, Tamoxifen) or mimicking GnRH (Gonadorelin).

However, their efficacy depends on the ability of the testicular Leydig cells to respond to the LH signal. If these cells are compromised by acetaldehyde toxicity and oxidative stress, the response will be blunted, prolonging the recovery period and reducing the protocol’s effectiveness. The entire therapeutic effort is hampered by a fundamental impairment at the terminal end of the signaling cascade.

Similarly, the benefits of tissue-repair peptides like Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) or sexual health peptides like PT-141 rely on a healthy cellular environment. PDA functions to repair tissues and reduce inflammation. Alcohol consumption actively promotes the inflammatory and oxidative state that these peptides are meant to counteract, creating a futile cycle.

PT-141 acts on melanocortin receptors in the brain to influence libido. Alcohol’s disruptive effect on central neurotransmitters can interfere with the very pathways PT-141 is designed to stimulate. Therefore, from a rigorous biochemical standpoint, concurrent alcohol use fundamentally compromises the molecular environment required for these protocols to achieve their intended effects.

References

- Rachdaoui, N. & Sarkar, D. K. (2017). Effects of Alcohol on the Endocrine System. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 46(1), 169 ∞ 189.

- Rachdaoui, N. & Sarkar, D. K. (2013). Pathophysiology of the effects of alcohol abuse on the endocrine system. Alcohol research ∞ current reviews, 35(2), 255 ∞ 276.

- Emanuele, M. A. & Emanuele, N. V. (1998). Alcohol and the male reproductive system. Alcohol research & health ∞ the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 22(3), 195 ∞ 201.

- Wu, D. & Cederbaum, A. I. (2003). Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol research & health ∞ the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 27(4), 277 ∞ 284.

- Li, Y. Chang, S. Liu, C. Ju, Y. Li, J. & Zhao, Y. (2013). The effect of alcohol consumption on the ovarian reserve in Chinese women. Journal of women’s health (2002), 22(11), 947 ∞ 952.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Dialogue

The information presented here is a tool for introspection. It provides a biological narrative for feelings and symptoms that may have been previously disconnected or dismissed. The purpose is to shift the internal conversation from one of passive acceptance to one of active awareness.

How does your body feel the morning after a drink, not just in terms of a hangover, but in the subtle language of energy, mood, and clarity? What patterns emerge in your sleep, your recovery from exercise, or your overall sense of vitality when you alter this single variable? This knowledge empowers you to become a more attuned observer of your own physiology.

Understanding these complex interactions is the foundational step. The path toward optimizing your unique biological system is a personal one, built on this awareness and guided by a strategy tailored to your specific goals and biochemistry. Your health journey is a dynamic process of learning, adjusting, and recalibrating. The ultimate goal is to create an internal environment where your body’s intricate communication network can operate with clarity, precision, and resilience, allowing you to function at your full potential.