Fundamentals

The quiet fading of desire is an experience that can feel deeply personal and isolating. It often begins subtly, a slow turning down of a dial that once broadcasted a vibrant signal. You may notice it as a gentle detachment, a growing distance from a part of yourself that was once a source of connection and vitality.

This change is frequently attributed to stress, fatigue, or the simple progression of life, yet the biological reality is often rooted in the intricate and powerful world of your endocrine system. Understanding the long-term effects of untreated hormonal imbalances on libido is the first step toward reclaiming this essential aspect of your well-being.

It is a journey into the body’s internal communication network, a system where specific chemical messengers orchestrate not just reproductive function, but also energy, mood, and the very spark of sexual interest.

Your body operates through a sophisticated series of chemical signals, with hormones acting as the primary messengers. These molecules travel through the bloodstream, delivering instructions to various cells and organs, ensuring countless physiological processes run in concert. Libido, or sexual desire, is one of these processes, profoundly influenced by the precise balance of several key hormones.

When this equilibrium is disrupted for extended periods, the consequences for sexual health can be significant and progressive. The initial decline in desire can evolve into a more persistent state of low libido, affecting emotional intimacy and overall quality of life. Recognizing that this is a physiological issue, not a personal failing, is a critical shift in perspective. It opens the door to a clinical understanding of what is happening within your body and why.

The persistence of low libido is often a direct signal of an underlying, unaddressed shift in the body’s hormonal environment.

The Core Messengers of Desire

While a complex array of factors contributes to sexual desire, a few key hormones play starring roles. Their availability and balance are fundamental to the maintenance of a healthy libido in both men and women. An imbalance in any one of these can create a ripple effect throughout the endocrine system, impacting not only sexual function but also mood, energy, and cognitive clarity.

Testosterone is perhaps the most well-known hormone associated with libido. Produced in the testes in men and in smaller amounts in the ovaries and adrenal glands in women, it is a primary driver of sexual desire. When testosterone levels fall below the optimal physiological range, a condition known as hypogonadism, libido is one of the first functions to be affected.

In men, this can manifest as a noticeable drop in sexual thoughts and interest in sexual activity. In women, while the connection is more complex, adequate testosterone levels are essential for maintaining sexual arousal and responsiveness. The decline is often gradual, which can make it difficult to identify initially. Over time, however, the absence of this key androgen leads to a persistent and troubling lack of desire.

Estrogen, primarily considered a female hormone but also present in men, is another critical component of sexual health. In women, estrogen is vital for the physiological aspects of sexual function, such as maintaining the health and lubrication of vaginal tissues.

Low estrogen levels, which occur most dramatically during perimenopause and menopause, can lead to vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia (painful intercourse). This physical discomfort can, in turn, extinguish sexual desire. In men, the balance between testosterone and estrogen is important. Estrogen contributes to libido, erectile function, and spermatogenesis. When this balance is disrupted, sexual function can be impaired.

Progesterone, another key female hormone, works in concert with estrogen to regulate the menstrual cycle. Its direct influence on libido is less straightforward, but its calming, anti-anxiety effects can indirectly support sexual well-being.

High levels of progesterone can sometimes have a dampening effect on libido, while low levels can contribute to the overall hormonal chaos of perimenopause, including mood swings and sleep disturbances that detract from sexual desire. The interplay between these hormones is a delicate dance, and when one partner stumbles, the entire performance is affected.

Beyond the Bedroom the Systemic Impact of Hormonal Decline

The long-term consequences of untreated hormonal imbalances extend far beyond libido. The same hormones that fuel sexual desire are also integral to maintaining physical and mental health. Ignoring the warning sign of a diminished libido means overlooking a deeper systemic issue that can have far-reaching effects on your overall vitality and longevity. These are not isolated symptoms; they are indicators of a foundational disruption in your body’s operating system.

A prolonged state of low testosterone, for instance, is associated with a number of serious health concerns. It contributes to a decline in bone mineral density, increasing the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. It also leads to a loss of lean muscle mass and an increase in visceral fat, the metabolically active fat that surrounds the organs and drives inflammation.

This shift in body composition can elevate the risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. The connection between low testosterone and mental health is also well-documented, with studies showing a clear link to symptoms of depression, irritability, and cognitive fog. Men with untreated hypogonadism often report a diminished sense of well-being and a general lack of motivation, which further compounds the loss of libido.

For women, the hormonal fluctuations of perimenopause and the eventual decline in estrogen and testosterone during menopause bring a similar cascade of systemic effects. The loss of estrogen’s protective effects on the cardiovascular system can lead to an increased risk of heart disease. Bone density can decrease rapidly, leading to a heightened risk of osteoporosis.

Many women also experience mood swings, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and cognitive changes, often referred to as “brain fog.” These symptoms, combined with the physical discomfort of vaginal atrophy, create a powerful combination of factors that suppress sexual desire. The experience is a holistic one; when your body and mind are under duress, libido is often one of the first non-essential functions to be deprioritized.

The following table outlines the primary hormones involved in libido and their broader systemic functions, illustrating the interconnected nature of endocrine health.

| Hormone | Primary Role in Libido | Broader Systemic Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone |

Drives sexual desire, arousal, and frequency of sexual thoughts in both men and women. |

Maintains bone density, muscle mass, and red blood cell production. Influences mood, cognitive function, and energy levels. |

| Estrogen |

Supports physiological arousal in women by maintaining vaginal tissue health and lubrication. Contributes to libido in both sexes. |

Regulates the menstrual cycle, protects bone health, supports cardiovascular health, and influences mood and skin elasticity. |

| Progesterone |

Plays a complex, modulatory role. Can have a calming effect that supports intimacy, but high levels may suppress libido. |

Prepares the uterus for pregnancy, regulates the menstrual cycle, and has calming, sleep-promoting effects. |

| Thyroid Hormones (T3/T4) |

Indirectly influences libido by regulating overall metabolism and energy levels. Hypothyroidism is a common cause of low desire. |

Controls metabolic rate, heart rate, body temperature, and plays a role in nearly every organ system. |

Intermediate

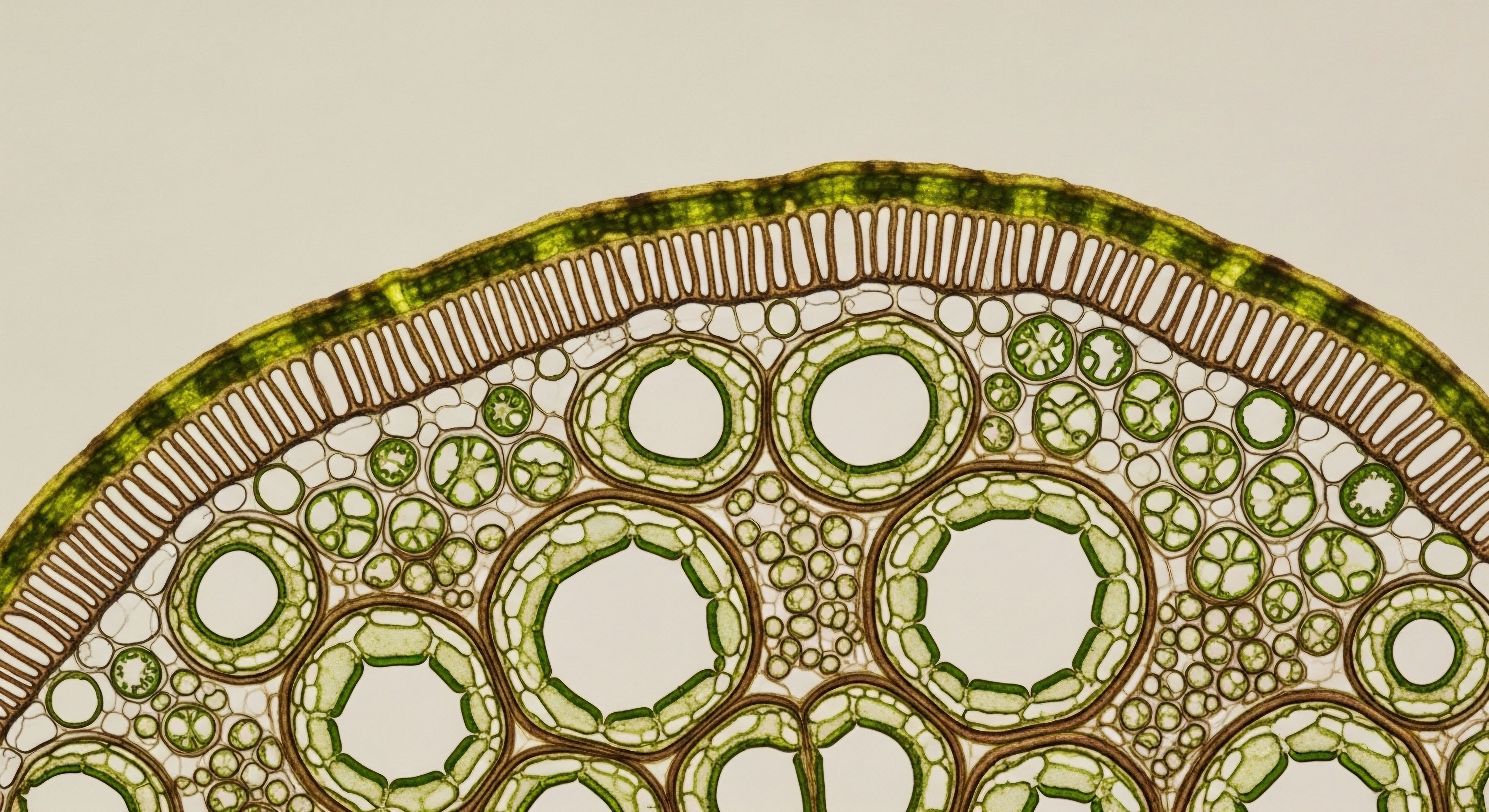

To truly grasp the long-term erosion of libido from hormonal imbalances, we must look beyond individual hormones and examine the system that governs them. Your body’s endocrine function is not a loose collection of glands; it is a highly organized, hierarchical system known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

This axis is the central command and control for your entire reproductive and sexual hormonal milieu. Think of it as a sophisticated internal thermostat, constantly monitoring and adjusting hormone levels to maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium. When this communication pathway becomes dysregulated over a long period, the signal for desire grows faint, and the body’s capacity for sexual response diminishes.

The process begins in the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that acts as the primary sensor. It monitors circulating levels of sex hormones and other inputs, such as stress and energy availability. In response to perceived low levels, the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner.

This pulse of GnRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the master gland of the endocrine system. The pituitary, in turn, releases two other hormones ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins travel through the bloodstream to the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women.

In men, LH stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone. In women, LH and FSH orchestrate the menstrual cycle, prompting the ovaries to produce estrogen and progesterone, as well as a smaller amount of testosterone.

The sex hormones produced by the gonads then circulate throughout the body, carrying out their various functions and also providing feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary, which tells them to slow down GnRH, LH, and FSH production. This is a negative feedback loop, and its integrity is essential for hormonal stability.

Dysfunction within the HPG axis creates a persistent hormonal deficit that directly translates into a diminished capacity for sexual desire.

When the Communication Breaks Down

Untreated hormonal imbalance is, at its core, a long-term failure of this feedback loop. The disruption can occur at any point along the HPG axis. It can be a primary issue, where the gonads themselves are unable to produce sufficient hormones despite receiving the correct signals.

This is common in cases of age-related decline, such as menopause or andropause, or due to direct damage to the testes or ovaries. The disruption can also be secondary, where the hypothalamus or pituitary fails to send the appropriate signals.

This can be caused by a variety of factors, including chronic stress, poor nutrition, excessive exercise, or the presence of a pituitary tumor. In either case, the result is a sustained state of hormonal deficiency that the body cannot correct on its own.

Over time, the body begins to adapt to this new, lower hormonal baseline. The receptors in the brain and other tissues that respond to hormones like testosterone become less sensitive. The neural pathways associated with sexual arousal and reward receive less stimulation, leading to a gradual unlearning of the desire response.

This is why the loss of libido in untreated hormonal imbalance is so insidious. It is a slow, physiological retreat from sexual function, driven by a breakdown in the body’s own internal communication system. The long-term effects are a cascade of consequences that begin with a quieted libido and extend to metabolic health, bone density, and psychological well-being.

Clinical Protocols for Restoring the Signal

When the HPG axis is unable to maintain hormonal balance on its own, clinical intervention may be necessary to restore physiological levels and alleviate symptoms, including low libido. Hormonal optimization protocols are designed to supplement the body’s own production, effectively bypassing the broken feedback loop.

These treatments are highly personalized and require careful medical supervision to ensure safety and efficacy. The goal is to restore hormone levels to a range that is optimal for the individual, based on their symptoms and laboratory testing.

For men with diagnosed hypogonadism (low testosterone), Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is the standard of care. The Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines recommend TRT for men who exhibit both consistent symptoms of testosterone deficiency and unequivocally low testosterone levels in their bloodwork. The most common protocol involves weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate. This approach provides a stable level of testosterone in the body, avoiding the peaks and troughs that can occur with other delivery methods.

- Testosterone Cypionate ∞ Typically administered at a dose of 100-200mg per week, this is the cornerstone of therapy, directly addressing the testosterone deficiency.

- Gonadorelin or HCG ∞ To prevent testicular atrophy and preserve fertility, a GnRH analogue like Gonadorelin may be prescribed. It mimics the action of GnRH, stimulating the pituitary to release LH and FSH, which in turn tells the testes to continue their own production of testosterone and sperm.

- Anastrozole ∞ In some men, a portion of the supplemental testosterone can be converted into estrogen through a process called aromatization. While some estrogen is necessary, excess levels can lead to side effects like water retention or gynecomastia. Anastrozole is an aromatase inhibitor that blocks this conversion, helping to maintain a healthy testosterone-to-estrogen ratio.

For women, the approach to hormonal therapy is more nuanced, reflecting the complex interplay of hormones in the female body. For women experiencing low libido, particularly during the menopausal transition, low-dose testosterone therapy can be highly effective. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health has issued guidelines for the use of testosterone in treating Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD). The protocols are tailored to the individual’s menopausal status and symptoms.

- Testosterone Cypionate for Women ∞ A much lower dose than that used for men, typically 10-20 units (0.1-0.2ml of a 200mg/ml solution) per week, administered subcutaneously. This small dose is often sufficient to restore libido without causing masculinizing side effects.

- Progesterone ∞ For post-menopausal women who still have a uterus, progesterone is prescribed alongside any estrogen therapy to protect the uterine lining. For peri-menopausal women, cyclic progesterone can help regulate cycles and alleviate symptoms like anxiety and insomnia.

- Pellet Therapy ∞ Another option for both men and women involves the subcutaneous implantation of small, long-acting pellets of testosterone. These pellets release a steady dose of the hormone over several months, offering a convenient alternative to weekly injections.

How Can One Navigate the Diagnostic Process?

If you suspect a hormonal imbalance is at the root of your low libido and other symptoms, a systematic approach to diagnosis is key. The journey begins with a comprehensive consultation with a clinician who specializes in hormonal health. This process involves more than just a single blood test; it is a holistic evaluation of your symptoms, health history, and lifestyle.

The first step is a detailed symptom assessment. Your clinician will want to understand the full scope of your experience, including changes in energy, mood, sleep, body composition, and cognitive function, in addition to your sexual health concerns. This subjective information is critically important, as it provides the context for interpreting laboratory results. Many individuals with symptoms of hormonal imbalance may have lab values that fall within the “normal” range, yet are far from optimal for their individual physiology.

The second step is comprehensive laboratory testing. This should go beyond a simple total testosterone level. A thorough panel will provide a complete picture of your HPG axis function. The following table details some of the key markers that should be evaluated.

| Lab Marker | What It Measures | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Testosterone |

The total amount of testosterone circulating in the blood, including both bound and unbound forms. |

A primary indicator of overall testosterone production. Low levels are a key diagnostic criterion for hypogonadism. |

| Free Testosterone |

The small fraction of testosterone that is unbound and biologically active, able to interact with cell receptors. |

A more accurate measure of the testosterone that is available for the body to use. Levels can be low even when total testosterone is normal. |

| SHBG (Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin) |

A protein that binds to sex hormones, primarily testosterone and estrogen, rendering them inactive. |

High levels of SHBG can lead to low free testosterone, even with normal total testosterone. It provides important context for interpreting testosterone levels. |

| Estradiol (E2) |

The primary form of estrogen in the body. |

Essential for assessing the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio in men and for diagnosing estrogen deficiency in women. |

| LH and FSH |

The pituitary hormones that signal the gonads to produce sex hormones. |

Helps to determine if a hormonal deficiency is primary (a problem with the gonads) or secondary (a problem with the pituitary or hypothalamus). |

| DHEA-S |

A precursor hormone produced by the adrenal glands that can be converted into testosterone and estrogen. |

Low levels can indicate adrenal fatigue and contribute to overall low androgen levels. |

| Comprehensive Thyroid Panel |

Includes TSH, Free T3, and Free T4. |

Rules out hypothyroidism, a common and often overlooked cause of low libido, fatigue, and depression. |

The final step is the integration of your symptoms and lab results to form a complete clinical picture. An experienced clinician will use this information to develop a personalized treatment plan that may include hormonal optimization, lifestyle modifications, and targeted nutritional support. This comprehensive approach ensures that the root cause of the hormonal imbalance is addressed, leading to a more sustainable restoration of libido and overall vitality.

Academic

The sustained loss of libido resulting from untreated hormonal imbalance represents a complex neuroendocrine phenomenon, the full scope of which can only be appreciated through a systems-biology lens. The issue is a profound dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, a master regulatory system whose integrity is foundational to reproductive capacity, metabolic homeostasis, and psychosexual health.

The long-term consequences are not merely a linear decline in a single hormone but a systemic unraveling of interconnected signaling pathways. This includes the intricate crosstalk between the HPG axis and other critical neuroendocrine systems, most notably the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, which controls metabolism. Understanding this interplay is essential for comprehending the deep, progressive nature of libido loss in these conditions.

At the molecular level, sex hormones, particularly testosterone and estradiol, function as powerful neuromodulators. They exert their influence by binding to specific intracellular receptors located in key areas of the brain associated with sexual motivation and behavior, including the hypothalamus, amygdala, and preoptic area.

These hormone-receptor complexes act as transcription factors, directly altering gene expression and influencing the synthesis and sensitivity of critical neurotransmitter systems. Specifically, androgens and estrogens have been shown to modulate the dopaminergic pathways, which are central to motivation and reward, and the serotonergic system, which plays a complex role in mood and impulse control.

A chronic deficiency of these sex hormones leads to a down-regulation of these neural circuits. The brain’s reward system becomes less responsive to sexual cues, and the motivational drive to seek out sexual activity is diminished. This is a process of neural adaptation to a low-hormone environment, a biological recalibration that prioritizes survival over procreation.

The chronic absence of adequate hormonal signaling leads to a functional and structural remodeling of the neural circuits that govern sexual motivation.

The Inter-Axis Crosstalk HPG HPA and HPT

The human body does not operate in silos. The HPG, HPA, and HPT axes are deeply intertwined, with the functional status of one directly influencing the others. Chronic stress, mediated by the HPA axis, is a powerful suppressor of the HPG axis.

The sustained elevation of cortisol, the primary stress hormone, has an inhibitory effect on the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. This, in turn, suppresses the entire downstream cascade of LH, FSH, and gonadal hormone production.

In a state of chronic stress, the body effectively decides that the environment is not safe for reproduction, and it shunts resources away from the HPG axis to fuel the fight-or-flight response. This interaction explains why individuals under significant, prolonged stress often experience a profound loss of libido. It is a physiologically adaptive, albeit subjectively distressing, response.

Similarly, the function of the thyroid gland, governed by the HPT axis, is critical for sexual health. Thyroid hormones are necessary for the normal metabolic function of all cells, including those in the gonads and the brain. Hypothyroidism, a state of low thyroid function, is a well-established cause of low libido in both sexes.

It can directly impair testicular and ovarian function, and it also increases levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), which reduces the amount of free, bioavailable testosterone. Furthermore, the symptoms of hypothyroidism ∞ fatigue, depression, weight gain, and cognitive slowing ∞ are themselves powerful inhibitors of sexual desire. The interplay is bidirectional; severe, prolonged hypogonadism can also impact thyroid function, creating a vicious cycle of endocrine disruption.

The long-term consequence of an untreated imbalance in one axis is often a progressive dysregulation of the others. A primary failure of the HPG axis, as seen in menopause or andropause, can reduce the body’s resilience to stress, leading to a hyper-reactive HPA axis.

The resulting hormonal environment is one of low anabolic, pro-libido hormones (testosterone, estrogen) and high catabolic, anti-libido hormones (cortisol). This state is fundamentally incompatible with a healthy sexual response and contributes to the broader clinical picture of accelerated aging, including sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and cognitive decline.

What Is the Cellular Basis for Hormonal Resistance?

Over time, a chronic deficiency of sex hormones can lead to a state of hormonal resistance at the cellular level. The receptors that bind to these hormones can become down-regulated or desensitized. This means that even if hormone levels were to be restored, the cells may not be able to respond as effectively as they once did.

This phenomenon is particularly relevant in the central nervous system, where the plasticity of neural circuits is constantly being shaped by hormonal input. The brain adapts to the low-hormone state, and the pathways that mediate desire become less efficient.

This concept of resistance highlights the importance of timely intervention. While hormonal optimization protocols can restore physiological levels of hormones in the bloodstream, overcoming established cellular resistance can be a more prolonged process. It may require a period of sustained hormonal therapy to encourage the up-regulation of receptors and the restoration of normal cellular signaling.

This is why some individuals may not experience a full return of libido immediately upon starting treatment. The body needs time to relearn how to respond to the hormonal signals it has been missing.

The following is a list of key biological processes that are impacted by long-term untreated hormonal imbalances, leading to a decline in libido:

- Neurotransmitter Dysregulation ∞ Chronic low levels of testosterone and estrogen disrupt the delicate balance of dopamine and serotonin in the brain. Dopamine, which is crucial for motivation and reward, is often down-regulated, leading to a lack of interest in sexual activity. Serotonin’s complex role can also be altered, contributing to mood changes that negatively impact libido.

- Nitric Oxide Pathway Impairment ∞ Nitric oxide (NO) is a critical signaling molecule for erectile function in men and clitoral engorgement in women. Testosterone plays a key role in maintaining the health of the endothelial cells that produce NO. Long-term testosterone deficiency can lead to endothelial dysfunction, impairing blood flow to the genitals and reducing the physical capacity for arousal.

- Sensory Nerve Atrophy ∞ Sex hormones are essential for the maintenance of sensory nerves in the genital tissues. Prolonged deficiency can lead to a degree of atrophy in these nerves, reducing sensitivity and diminishing the pleasurable sensations associated with sexual activity. This can create a feedback loop where reduced physical pleasure further dampens psychological desire.

- Intracrine Hormone Metabolism ∞ The brain and other peripheral tissues have the ability to synthesize their own active sex steroids from precursor hormones like DHEA. This process, known as intracrinology, is an important source of neurosteroids that influence mood and libido. Age-related decline in DHEA production, combined with a failing HPG axis, can starve the brain of these locally produced androgens and estrogens, further contributing to the decline in sexual desire.

In conclusion, the long-term effect of untreated hormonal imbalance on libido is a multifactorial process of progressive neuroendocrine and physiological decline. It is a systems-level failure that begins with the dysregulation of the HPG axis and ramifies throughout the body’s interconnected signaling networks.

The result is a profound and persistent suppression of the biological machinery of desire, impacting not only sexual function but also overall health, vitality, and quality of life. The clinical approach to this condition requires a deep understanding of these complex interactions and a commitment to restoring physiological balance in a safe and sustainable manner.

References

- Bhasin, S. Brito, J. P. Cunningham, G. R. Hayes, F. J. Hodis, H. N. Matsumoto, A. M. Snyder, P. J. Swerdloff, R. S. Wu, F. C. & Yialamas, M. A. (2018). Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(5), 1715 ∞ 1744.

- Snipes, D. E. (2022, March 9). HPG Axis Sex Hormones and Mental Health. YouTube.

- Khera, M. (2016). Male Hormones and Men’s Quality of Life. Current Opinion in Urology, 26(2), 152-157.

- Rastrelli, G. & Maggi, M. (2017). The association of hypogonadism with depression and its treatments. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, 12(2), 103-114.

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Male hypogonadism – Symptoms & causes. Mayo Clinic.

- International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health. (2021). International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Systemic Testosterone for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(5), 849-867.

- Layton, L. L. & Legros, G. (2012). Disorders of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. In Handbook of Neuroendocrinology (pp. 659-683). Elsevier Inc.

- Corona, G. Giammusso, B. & Serefoglu, E. C. (2021). Hypothalamic ∞ Pituitary Diseases and Erectile Dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(12), 2577.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map of the complex biological territory that governs sexual desire. It details the pathways, the messengers, and the systems that must work in concert to create and sustain this vital aspect of human experience.

This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the conversation about libido from one of shame or confusion to one of clinical clarity and physiological understanding. You now have a framework for comprehending the subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, signals your body may be sending.

This understanding is the starting point of a deeply personal investigation. Your own lived experience, the unique narrative of your health journey, provides the essential context for this scientific map. How do these concepts resonate with your own story of energy, mood, and desire?

Where do you see parallels between the clinical descriptions and your personal reality? The path forward involves integrating this objective knowledge with your subjective truth. It is about recognizing that you are the foremost expert on your own body.

The goal is to move forward not with a set of generic answers, but with a more refined set of questions to explore with a trusted clinical partner. This journey is about reclaiming function, vitality, and a part of yourself that may have felt lost, armed with the empowering knowledge of your own intricate biology.