Fundamentals

The decision to pursue a physical transformation is deeply personal. It often begins with a clear vision of a stronger, more capable self. This drive is a powerful motivator, pushing you to train harder and seek every possible advantage. When considering the use of androgens to accelerate this process, you are contemplating the use of potent biological messengers.

Understanding how your body communicates with itself is the first step in comprehending the gravity of this choice. Your endocrine system functions as a sophisticated internal communication network, with the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis acting as the central command. This axis is a finely tuned feedback loop, a biological thermostat that constantly monitors and adjusts the production of your body’s natural androgens, like testosterone.

The hypothalamus, located in the brain, senses the body’s need for testosterone and releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This signal travels to the pituitary gland, another structure in the brain, prompting it to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then travel through the bloodstream to the gonads ∞ the testes in men.

In response to LH, the testes produce testosterone. As testosterone levels rise in the blood, this increase is detected by both the pituitary and the hypothalamus, which then reduce their signaling to prevent overproduction. This entire process maintains a precise hormonal equilibrium, a state of balance essential for everything from mood and energy to metabolic health and reproductive function.

Introducing external androgens from an unsupervised source fundamentally disrupts this sensitive biological conversation.

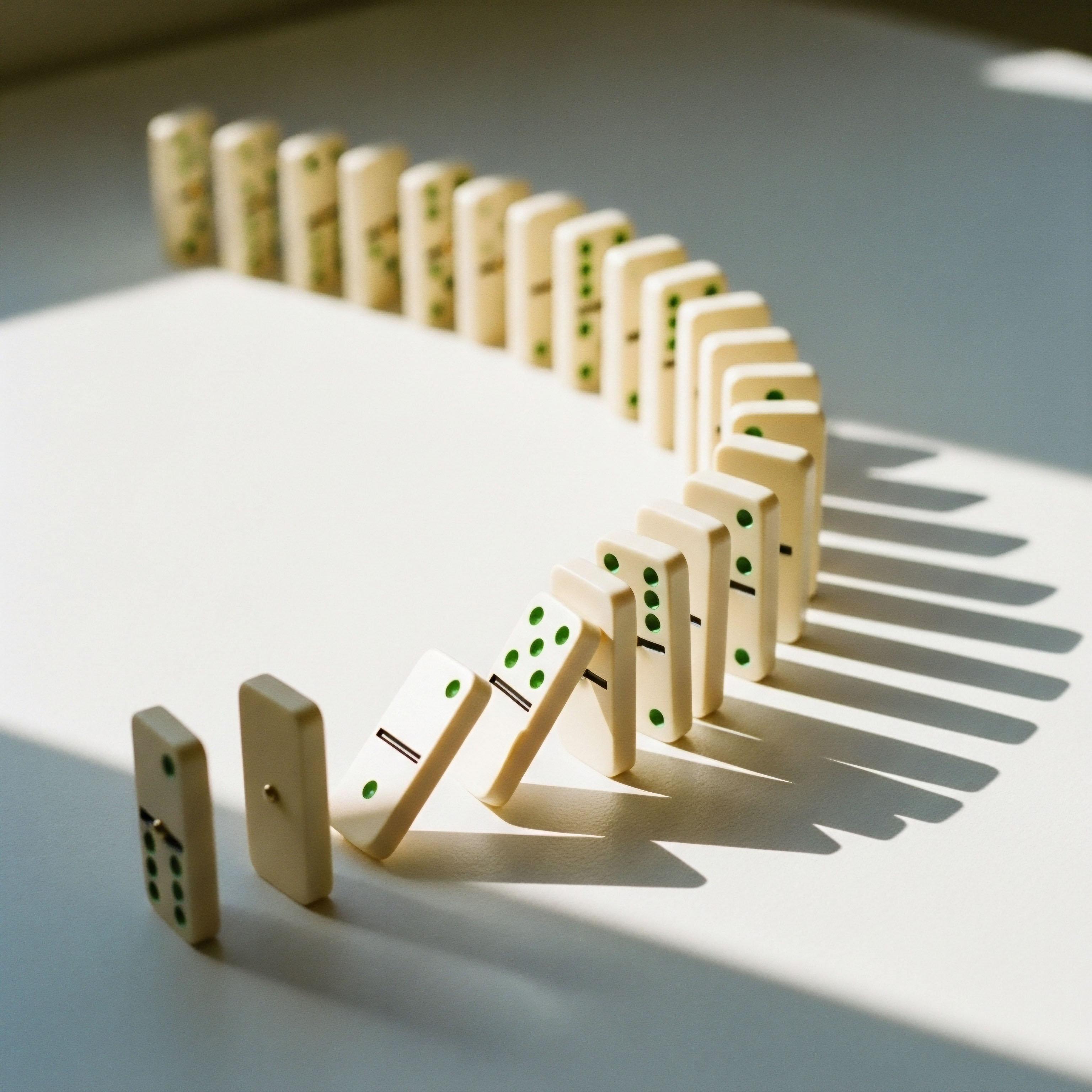

When you introduce supraphysiological doses of androgens from an outside source, the HPG axis interprets this massive influx as a signal to shut down its own production completely. Your hypothalamus and pituitary sense an overwhelming abundance of androgens and cease sending signals to the testes. The body’s natural testosterone factory goes silent.

This shutdown is the foundational event from which many long-term consequences originate. The body is designed for hormonal precision, and flooding the system with powerful external compounds without medical guidance creates a cascade of biological reactions that extend far beyond muscle tissue.

What Is the Body’s Initial Response?

Initially, the effects you seek may be pronounced. An increase in protein synthesis leads to rapid gains in muscle mass and strength. There might be a heightened sense of well-being or aggression. These immediate, tangible results can be affirming, reinforcing the decision to use these compounds.

Beneath the surface, however, the body is already beginning to adapt in ways that carry significant long-term risk. The liver, your body’s primary filtration system, immediately begins working to metabolize these new, often chemically-modified substances. The cardiovascular system starts to respond to altered fluid balances and lipid profiles.

The brain’s neurochemistry begins to shift in response to the potent hormonal signaling. These initial adaptations are the quiet prelude to more serious, systemic changes that develop over time with continued, unsupervised use.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial shutdown of the HPG axis, the long-term consequences of unsupervised androgen use manifest across multiple physiological systems. These are not isolated side effects; they are the logical outcomes of sustained endocrine disruption. The absence of clinical oversight means these changes proceed unchecked, often without obvious symptoms until significant damage has occurred.

A medically supervised protocol is designed specifically to mitigate these risks through careful dosage, monitoring of blood markers, and the use of ancillary medications to protect the body’s intricate systems. Without this clinical framework, the user is navigating a complex biochemical landscape alone.

Cardiovascular System under Duress

The heart and blood vessels are particularly vulnerable to the effects of supraphysiological androgen levels. One of the most well-documented consequences is the development of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), a condition where the main pumping chamber of the heart thickens and stiffens.

This structural change impairs the heart’s ability to relax and fill with blood properly (diastolic dysfunction) and can eventually weaken its ability to pump blood effectively (systolic dysfunction). This is a direct result of androgens acting on receptors within the heart muscle itself, promoting abnormal growth.

Simultaneously, unsupervised androgen use negatively alters blood lipid profiles. It characteristically suppresses High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL), the “good” cholesterol that removes deposits from arteries, while increasing Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL), the “bad” cholesterol that contributes to plaque buildup. This shift creates a highly atherogenic environment, dramatically accelerating the process of atherosclerosis, or the hardening and narrowing of the arteries.

This process, combined with androgen-induced increases in blood pressure and a higher propensity for blood clot formation, substantially elevates the long-term risk for heart attack, stroke, and sudden cardiac death.

The structural and functional changes to the heart from unsupervised androgen use can lead to irreversible cardiac damage.

The following table outlines the primary cardiovascular risks associated with long-term, unsupervised use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS).

| Cardiovascular Risk | Underlying Mechanism | Potential Long-Term Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH) | Direct stimulation of androgen receptors on cardiac myocytes; increased blood pressure and cardiac workload. | Diastolic and systolic dysfunction, heart failure, arrhythmias. |

| Dyslipidemia | Suppression of HDL cholesterol and elevation of LDL cholesterol. | Accelerated atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease. |

| Hypertension | Increased sodium and water retention mediated by effects on the kidney; potential alterations to the renin-angiotensin system. | Increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and kidney damage. |

| Prothrombotic State | Increased platelet aggregation and activation of blood clotting factors. | Venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, heart attack. |

The Endocrine Echo and Lasting Hypogonadism

While the HPG axis shutdown is immediate, the recovery from this state is far from guaranteed. After cessation of unsupervised androgen use, the body enters a state of Anabolic Steroid-Induced Hypogonadism (ASIH). This is a period where the user’s own hormonal production remains suppressed, yet the external androgens have been removed. The result is a profound state of testosterone deficiency. Symptoms during this withdrawal phase can be severe:

- Severe Fatigue ∞ A persistent lack of physical and mental energy.

- Depression and Anxiety ∞ Profound mood disturbances are common as brain chemistry readjusts.

- Loss of Libido ∞ A complete disinterest in sexual activity is a hallmark of ASIH.

- Loss of Muscle Mass ∞ The anabolic support is gone, and the body’s catabolic processes dominate.

- Increased Body Fat ∞ Metabolic function is disrupted, leading to fat accumulation.

The duration of ASIH is highly variable and depends on the types of compounds used, the dosages, and the length of use. For some, the HPG axis may slowly restart over several months or even years.

For others, particularly after long or heavy cycles, the suppression can be permanent, leaving them with a lifelong dependency on medically prescribed testosterone replacement therapy to feel normal. Furthermore, the shutdown of FSH production leads to a cessation of spermatogenesis, resulting in infertility.

While often reversible, the return of fertility can be a long and uncertain process. Gynecomastia, the development of breast tissue due to the conversion of excess androgens to estrogens, is another common effect that is typically irreversible without surgical intervention.

Hepatic and Neuropsychiatric Consequences

The liver is the organ responsible for metabolizing drugs, and androgens, particularly orally active 17-alpha-alkylated steroids, place a significant strain on it. Long-term use can lead to a range of liver injuries. Cholestasis, a condition where bile flow from the liver is blocked, is a common form of hepatotoxicity.

This can cause jaundice, itching, and fatigue. More severe and rarer complications include peliosis hepatis (blood-filled cysts in the liver) and the development of hepatic tumors, both benign (adenomas) and malignant (hepatocellular carcinoma).

The brain is also profoundly affected. Androgens cross the blood-brain barrier and influence neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine and serotonin. During use, this can manifest as increased aggression, irritability, and impulsivity. The withdrawal period, as noted, often brings severe depression.

Emerging research suggests that long-term, high-dose use may be associated with lasting structural and functional changes in the brain, including a thinning of the cortex and deficits in visuospatial memory. These findings point toward a potential for accelerated brain aging and cognitive decline.

Academic

A granular examination of the long-term effects of unsupervised androgen use reveals a complex pathophysiology centered on direct cellular signaling, maladaptive remodeling, and systemic homeostatic disruption. The cardiovascular system provides a particularly compelling case study of this process.

The progression from supraphysiological androgen exposure to clinical heart failure is not a random occurrence; it is a predictable cascade of molecular and structural events. Understanding these mechanisms at an academic level clarifies why the risks are so profound and why clinical intervention is essential for harm reduction.

What Are the Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiac Hypertrophy?

The development of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in users of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) is driven by both direct and indirect pathways. The direct mechanism involves the presence of androgen receptors (AR) on cardiac myocytes themselves.

When supraphysiological levels of androgens bind to these receptors, they activate intracellular signaling cascades that promote protein synthesis and cellular growth, mirroring the anabolic effect seen in skeletal muscle. This process leads to an increase in the physical size of the heart muscle cells, thickening the ventricular walls.

The indirect mechanisms are equally significant. AAS administration can disrupt the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS), a critical regulator of blood pressure and fluid balance. This disruption often leads to sodium and water retention, increasing total blood volume and subsequently elevating blood pressure.

The resulting hypertension increases cardiac afterload, meaning the heart must pump against higher resistance. This sustained pressure overload forces the heart muscle to adapt by hypertrophying, a compensatory mechanism that is ultimately maladaptive. This pathological hypertrophy is distinct from the physiological hypertrophy seen in endurance athletes; it is often accompanied by myocardial fibrosis, an accumulation of collagen that stiffens the heart wall and impairs its function.

Pathological cardiac remodeling from androgen use involves a shift from functional adaptation to fibrotic stiffening, impairing long-term heart performance.

The table below differentiates the primary molecular drivers of AAS-induced cardiac damage.

| Pathophysiological Process | Key Molecular Drivers | Resulting Cardiac Pathology |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Myocyte Growth | Binding of androgens to cardiac androgen receptors (AR); activation of protein synthesis pathways (e.g. mTOR). | Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy; increased myocardial mass. |

| Indirect Pressure Overload | AAS-induced disruption of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS); increased fluid retention and systemic vascular resistance. | Hypertension; further stimulus for compensatory hypertrophy. |

| Myocardial Fibrosis | Increased activity of angiotensin II; stimulation of cardiac fibroblasts to produce excess collagen. | Increased ventricular stiffness, diastolic dysfunction, arrhythmogenesis. |

| Accelerated Atherosclerosis | Suppression of hepatic lipase leading to low HDL; potential increase in LDL particles. | Coronary artery plaque formation and progression; ischemic heart disease. |

How Does Endocrine Suppression Become Permanent?

The persistence of Anabolic Steroid-Induced Hypogonadism (ASIH) relates to the concept of cellular “memory” and potential neurotoxicity within the HPG axis. The chronic overstimulation of androgen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary by exogenous hormones can lead to desensitization or downregulation of these receptors. The cells become less responsive to hormonal signals.

When the external androgens are removed, the returning low levels of endogenous testosterone may be insufficient to properly reactivate this suppressed and desensitized system. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that prolonged exposure to high levels of androgens may induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in certain neuronal populations, potentially including the GnRH-producing neurons in the hypothalamus.

Damage to this master regulatory center could permanently impair the body’s ability to restart its own testosterone production, transforming a temporary shutdown into a lasting clinical condition requiring lifelong hormonal support.

Why Is Liver Toxicity Specific to Certain Androgens?

The hepatotoxicity associated with AAS use is primarily linked to a specific chemical modification ∞ 17-alpha-alkylation. Native testosterone, when taken orally, is rapidly broken down by the liver during its first pass through the digestive system, rendering it ineffective. To create orally active steroids, a methyl or ethyl group is added at the 17th carbon position of the steroid molecule.

This 17-alpha-alkylation shields the compound from hepatic metabolism, allowing it to enter the bloodstream. This structural alteration is what makes these compounds so damaging to the liver. The liver struggles to break down these modified molecules, leading to intracellular stress.

The primary mechanism of injury is believed to be oxidative stress, where the metabolic process generates excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage hepatocytes. This cellular damage can manifest as cholestasis, where bile transport is impaired, or direct hepatocellular injury, leading to elevated liver enzymes. Injectable androgens that are not 17-alpha-alkylated bypass the first-pass metabolism and are generally considered less hepatotoxic, although they carry their own significant systemic risks.

References

- Baggish, A. L. et al. “Cardiovascular Toxicity of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids ∞ A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association.” Circulation, vol. 135, no. 19, 2017, pp. e1029-e1045.

- Rasmussen, J. J. et al. “Former Abusers of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids Exhibit Decreased Myocardial Function.” American Heart Journal, vol. 207, 2019, pp. 137-145.

- Pope, H. G. et al. “Brain and Cognition Abnormalities in Long-Term Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid Users.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 162, 2016, pp. 132-140.

- Nieschlag, E. & Vorona, E. “Mechanisms in Endocrinology ∞ Medical consequences of doping with anabolic androgenic steroids ∞ effects on reproductive functions.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 173, no. 2, 2015, pp. R47-R58.

- Bond, P. Llewellyn, W. & Van Mol, P. “Anabolic androgenic steroid-induced hepatotoxicity.” Medical Hypotheses, vol. 93, 2016, pp. 150-153.

- Kanayama, G. et al. “Anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence ∞ an emerging disorder.” Addiction, vol. 104, no. 12, 2009, pp. 1966-1978.

- de Ronde, W. & Smit, D. L. “Anabolic steroid-induced hypogonadism ∞ a challenge for clinicians.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 8, no. 10, 2020, pp. 810-811.

- Pirompol, P. et al. “Anabolic androgenic steroid-induced liver injury ∞ An update.” World Journal of Hepatology, vol. 14, no. 7, 2022, pp. 1357-1371.

- Frati, P. et al. “Anabolic Androgenic Steroid (AAS) related deaths ∞ autoptic, histopathological and toxicological findings.” Current Neuropharmacology, vol. 13, no. 1, 2015, pp. 146-159.

- Urhausen, A. et al. “Reversibility of subclinical cardiac abnormalities in bodybuilders after discontinuation of anabolic steroid use.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 36, no. 9, 2004, pp. 1501-1507.

Reflection

The information presented here maps the biological consequences of a specific choice. It traces the path from a single action to a cascade of systemic effects, from the shutdown of an elegant feedback loop to the structural remodeling of the heart. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose.

It provides a clear, unvarnished look at the internal processes that occur when powerful hormones are used outside of a clinical context. Your body is a system of profound complexity and resilience. Understanding its language, its rules of communication, and its reactions to external inputs is the foundational step in any health journey.

The path toward your personal goals can be navigated with strategies that honor your body’s intricate design, working with its systems rather than against them. This clinical understanding is the first tool for building a future of sustained vitality and function.