Fundamentals

The feeling is a familiar one. It begins as a low hum of pressure behind the eyes, the subtle tightening in the shoulders during a difficult meeting, or the sense of a mind that refuses to switch off long after the day is done.

You might recognize it as fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, a persistent irritability that feels disconnected from your immediate circumstances, or a creeping weight gain around the midsection that resists all dietary efforts. This lived experience is the starting point for understanding the profound biological conversation happening within your body.

Your symptoms are valid data points, signals from a highly intelligent system that is attempting to adapt to a relentless demand. This demand is chronic stress, and its management of your internal world is precise, systematic, and deeply impactful.

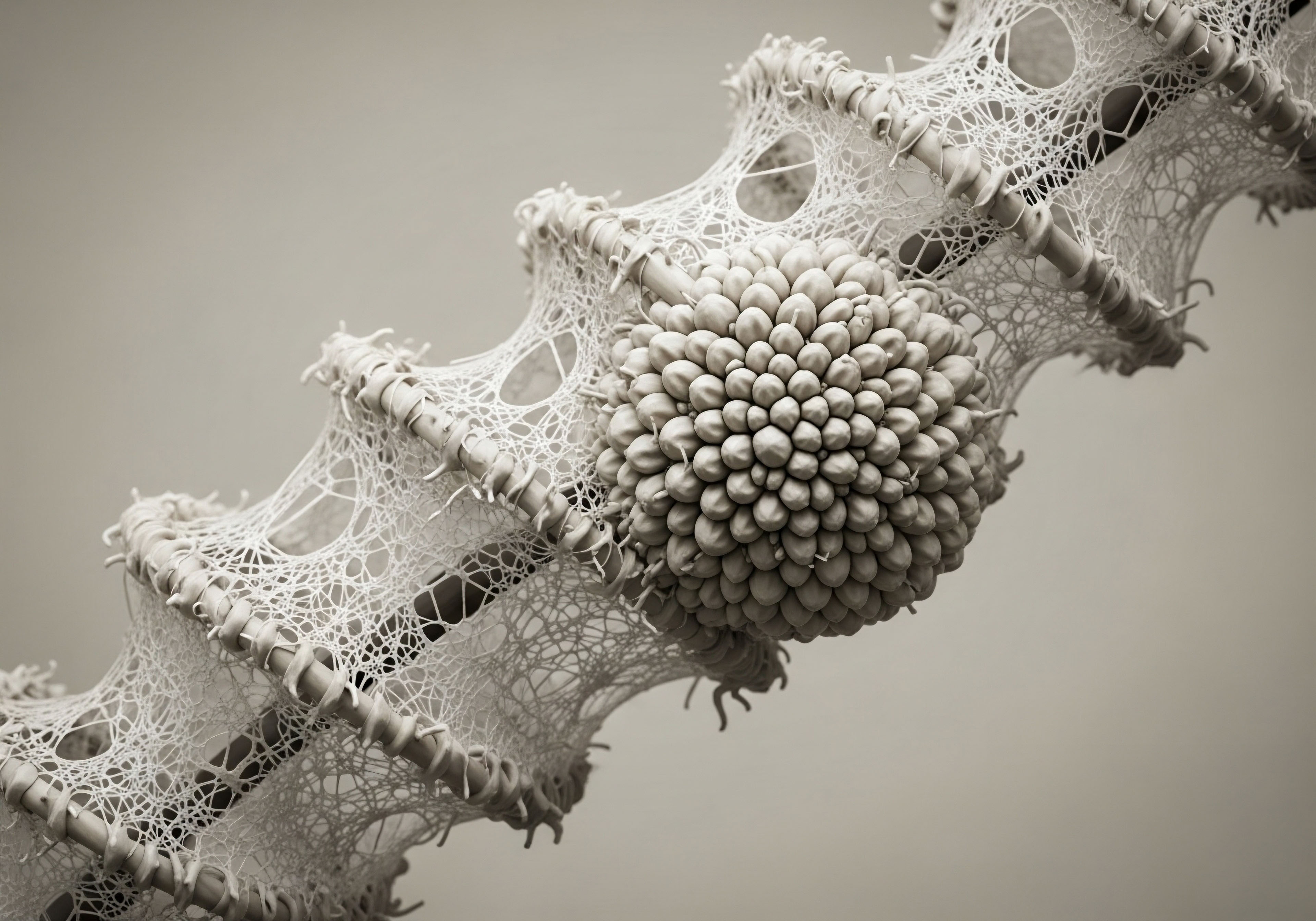

At the center of this response is a sophisticated command-and-control network known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This system is an ancient survival mechanism, a beautifully orchestrated cascade designed to prepare you for immediate, short-term threats.

When your brain perceives a stressor, your hypothalamus, a small but powerful region in your brain, releases a chemical messenger called Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH). CRH travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, the body’s master gland, instructing it to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH then journeys to your adrenal glands, which are perched atop your kidneys, and delivers its message ∞ release cortisol.

Cortisol is the body’s primary stress hormone, and its release initiates a series of metabolic changes designed for survival. It rapidly increases the amount of glucose in your bloodstream, providing an immediate source of energy for your muscles and brain. It heightens your focus and alertness, preparing you to confront the challenge at hand.

In these short bursts, cortisol is essential for life. It helps you wake up in the morning, perform under pressure, and mount an effective response to danger. After the perceived threat passes, the rising levels of cortisol in the blood signal the hypothalamus and pituitary gland to stop producing CRH and ACTH, a process known as a negative feedback loop.

This elegant system ensures the stress response is switched off, allowing the body to return to a state of balance, or homeostasis.

The Unrelenting Signal

The modern world presents a different kind of threat. The stressors are rarely a physical danger that can be fought or fled. Instead, they are persistent deadlines, financial worries, traffic, and the constant digital stimulation of a connected world. Your HPA axis, in its evolutionary wisdom, does not distinguish between a predator and a looming project deadline.

It perceives a threat and responds with its reliable cascade, releasing cortisol. When these stressors are constant and unmanaged, the HPA axis remains activated. The negative feedback loop that should shut the system down becomes less effective. The result is a body bathed in chronically elevated levels of cortisol.

Your body’s intelligent survival system, the HPA axis, responds to all perceived threats by releasing cortisol, a hormone essential in short bursts but disruptive when chronically elevated.

This state of prolonged cortisol exposure is where the first signs of trouble begin to manifest in ways you can feel. The constant demand for glucose can lead to intense sugar cravings as your body seeks to replenish the energy it believes it needs for a perpetual fight.

Cortisol’s influence on metabolism can direct the body to store fat, particularly visceral fat around the abdomen. You may experience digestive issues, as the body diverts resources away from functions it deems non-essential for immediate survival, like proper digestion and nutrient absorption.

Sleep becomes disrupted because the natural rhythm of cortisol, which should be highest in the morning and lowest at night, is flattened. You may feel “wired but tired,” a state of exhaustion combined with an inability to truly rest, as your system is kept on high alert. These symptoms are the first whispers of a deeper hormonal imbalance, the direct consequence of a survival system that has been left on for too long.

Beyond the Adrenals a System-Wide Conversation

The influence of chronic HPA axis activation extends far beyond simple fatigue or weight gain. Cortisol is a powerful steroid hormone that communicates with nearly every cell in the body. Its sustained presence begins to alter the function of other critical hormonal systems.

Think of it as a radio signal that is so loud it interferes with all other frequencies. The body’s other communication networks must strain to send and receive their own messages, leading to a progressive state of systemic dysregulation. This is the mechanism by which unmanaged stress moves from a feeling of being overwhelmed to a concrete, measurable shift in your body’s entire hormonal balance. Understanding this progression is the first step toward reclaiming your biological equilibrium.

The initial effects of this systemic disruption often appear as a general decline in well-being. Your immune system may become suppressed, leading to more frequent illnesses. Inflammation, which cortisol is meant to suppress, can begin to rise as the body’s cells become less sensitive to its signal.

You might notice changes in your mood, such as increased anxiety or feelings of depression, as cortisol directly influences neurotransmitter function in the brain. These are not isolated issues; they are interconnected signs of a system under duress.

They are the prelude to more significant, long-term hormonal shifts that can affect your reproductive health, your metabolic function, and your overall vitality. The journey into the specifics of these shifts reveals the true cost of unmanaged stress on your long-term health.

Intermediate

As the body remains in a state of high alert, the persistent signaling of the HPA axis begins to fundamentally alter the behavior of other primary endocrine systems. The body’s resources, both metabolic and hormonal, are continuously rerouted to manage the perceived perpetual crisis.

This process of adaptation, while necessary for short-term survival, leads to significant long-term consequences for hormonal networks that govern reproduction, metabolism, and energy. The two most significant systems affected are the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls reproductive hormones, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, which regulates your metabolism.

How Does Stress Impact Reproductive Hormones?

The HPA and HPG axes are intricately linked, sharing a common command center in the hypothalamus. In a balanced state, the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to produce Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones, in turn, stimulate the gonads ∞ the testes in men and the ovaries in women ∞ to produce testosterone and estrogen, respectively. This is the central axis of reproductive health. However, the molecules of the stress response have a suppressive effect on this system.

High levels of cortisol and CRH act directly on the hypothalamus and pituitary to inhibit the release of GnRH, LH, and FSH. The biological logic is one of survival; in a time of extreme stress, the body prioritizes immediate safety over procreation.

For men, this chronic suppression of the HPG axis leads to a measurable decline in testosterone production. This condition, known as secondary hypogonadism, can manifest in a variety of symptoms that are often attributed to aging alone.

These include persistent fatigue, a decline in libido, difficulty building or maintaining muscle mass, increased body fat, and cognitive issues like brain fog or a lack of motivation. When these symptoms become clinically significant, a protocol of Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) may be considered to restore hormonal balance.

A standard approach involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, often combined with medications like Gonadorelin to help maintain the body’s own testosterone production and Anastrozole to control the conversion of testosterone to estrogen.

For women, the disruption of the HPG axis by chronic stress is equally profound, though its presentation varies with their stage of life. In pre-menopausal women, the suppression of LH and FSH can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, anovulatory cycles (cycles without ovulation), and worsening symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

In peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women, whose hormonal systems are already in a state of flux, the added burden of HPA axis dysfunction can exacerbate symptoms like hot flashes, night sweats, mood swings, and sleep disturbances. The stress-induced suppression of the HPG axis can also impact testosterone levels in women, which are vital for libido, energy, and bone density.

For women experiencing these symptoms, hormonal optimization protocols may involve low-dose Testosterone Cypionate, often administered via subcutaneous injection, alongside progesterone to support mood and sleep, particularly for those in perimenopause or post-menopause.

| Symptom Category | Manifestation in Men | Manifestation in Women |

|---|---|---|

| Energy and Vitality |

Persistent fatigue, decreased stamina |

Chronic exhaustion, feeling “drained” |

| Mood and Cognition |

Irritability, low motivation, “brain fog” |

Increased anxiety, mood swings, difficulty concentrating |

| Physical Changes |

Loss of muscle mass, increased abdominal fat |

Weight gain, changes in body composition |

| Reproductive Health |

Low libido, erectile dysfunction, reduced fertility |

Irregular cycles, worsening PMS, low libido |

The Thyroid Connection Stress and Metabolism

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis is the body’s metabolic thermostat. It begins with the hypothalamus releasing Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH), which prompts the pituitary to secrete Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH). TSH then travels to the thyroid gland, instructing it to produce thyroid hormones, primarily Thyroxine (T4) and a smaller amount of Triiodothyronine (T3).

T4 is largely an inactive storage hormone that must be converted in peripheral tissues, such as the liver and gut, into the metabolically active T3. T3 is the hormone that actually enters the cells and regulates the speed of your metabolism, your heart rate, and your body temperature.

Chronically elevated cortisol actively disrupts both reproductive and thyroid hormone pathways, leading to a cascade of symptoms that affect everything from energy levels to metabolic rate.

Chronic stress and high cortisol levels interfere with this elegant system in several ways. Firstly, elevated cortisol can suppress the pituitary gland’s release of TSH, effectively turning down the signal to the thyroid gland to produce hormones. This can result in lower overall thyroid hormone production.

Secondly, and perhaps more significantly, cortisol inhibits the crucial conversion of inactive T4 to active T3. It can also promote the conversion of T4 into an inactive form called Reverse T3 (rT3), which further blocks the action of T3 at the cellular level.

This creates a situation where standard thyroid tests that only measure TSH and T4 may appear normal, yet the individual experiences all the symptoms of hypothyroidism because their body cannot produce enough of the active T3 hormone. These symptoms include:

- Persistent fatigue ∞ A deep, cellular exhaustion that is not relieved by rest.

- Unexplained weight gain ∞ A slowing metabolism makes it difficult to lose weight, even with diet and exercise.

- Cold intolerance ∞ A feeling of being cold when others are comfortable, due to a lower metabolic rate.

- Hair loss and dry skin ∞ Reduced cellular activity affects the health of hair follicles and skin.

- Brain fog and depression ∞ Thyroid hormones are critical for proper neurotransmitter function.

When the Body Stops Listening Glucocorticoid Resistance

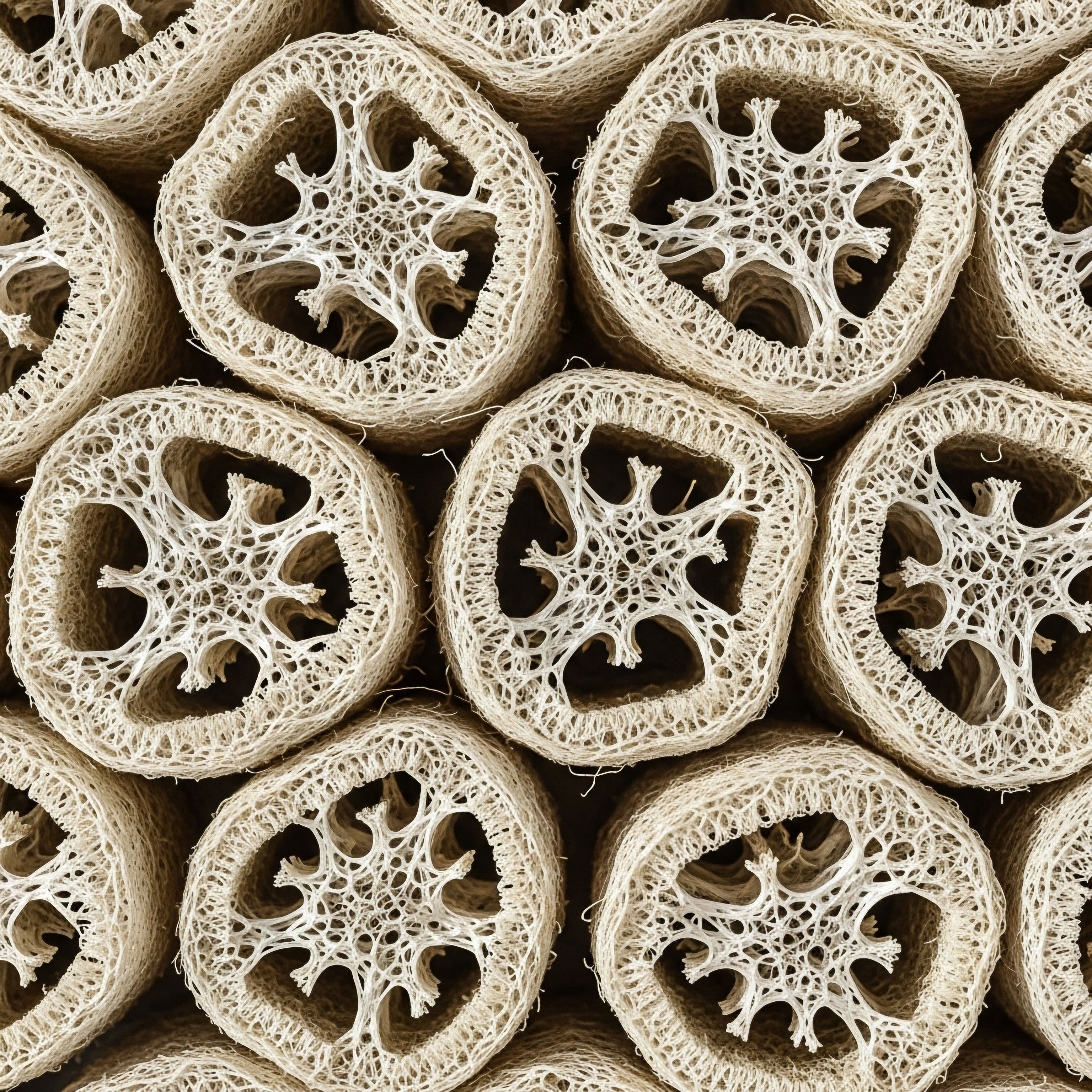

One of the most critical long-term effects of unmanaged stress is the development of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) resistance. After prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels, the receptors on the surface of your cells that are meant to bind with cortisol and receive its signal become less sensitive.

It is the biological equivalent of tuning out a constant noise. This desensitization has two devastating consequences. First, the HPA axis feedback loop is further impaired. Since the hypothalamus and pituitary are now less sensitive to cortisol’s “stop” signal, they continue to produce CRH and ACTH, leading to even more cortisol release in a dysfunctional attempt to be heard.

Second, and more consequentially, cortisol’s primary anti-inflammatory function is lost. Normally, cortisol keeps the immune system in check and prevents excessive inflammation. When cells become resistant to cortisol’s signal, inflammatory processes are no longer properly regulated. This allows low-grade, systemic inflammation to flourish throughout the body.

This state of chronic inflammation is a major contributing factor to a wide range of modern diseases, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and autoimmune conditions. It creates a vicious cycle where chronic stress leads to cortisol resistance, which leads to inflammation, which itself is a physiological stressor that further activates the HPA axis. This mechanism is central to how chronic stress translates into chronic disease.

Academic

The progression from an acute stress response to a state of chronic hormonal dysregulation is underpinned by complex molecular and cellular adaptations. At a high level, this process is understood as allostatic overload, where the cumulative cost of adapting to persistent stressors exceeds the body’s capacity to maintain homeostasis.

A deeper examination reveals specific mechanisms at the level of receptor genetics, intracellular signaling, and inter-axis crosstalk that drive the pathophysiology of stress-induced endocrine disorders. The central phenomenon in this cascade is the development of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) resistance, a state of diminished cellular sensitivity to cortisol that disrupts the body’s most critical feedback loops and unleashes systemic inflammation.

Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Receptor Resistance

The glucocorticoid receptor is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that, upon binding with cortisol, translocates to the nucleus to act as a ligand-dependent transcription factor. It modulates the expression of thousands of genes, typically upregulating anti-inflammatory genes and repressing pro-inflammatory genes. Chronic exposure to high concentrations of glucocorticoids, as seen in unmanaged stress, induces several molecular changes that impair this process.

One key mechanism involves the expression and function of GR isoforms. The primary functional receptor is GRα. However, alternative splicing of the GR gene can produce other isoforms, such as GRβ, which does not bind to glucocorticoids and acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of GRα.

Studies have shown that chronic stress and the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines can shift the splicing process to favor the production of GRβ, thereby increasing the GRβ/GRα ratio. A higher proportion of the inhibitory GRβ isoform effectively reduces the cell’s overall sensitivity to cortisol, contributing directly to a state of resistance.

Another critical component is the chaperone protein system that regulates GR function. In its unbound state, GR resides in the cytoplasm as part of a multi-protein complex that includes heat shock proteins and immunophilins. The immunophilin FK506-binding protein 51 (FKBP5) plays a particularly important role.

FKBP5 binds to the GR complex and reduces its affinity for cortisol. The gene for FKBP5 contains glucocorticoid response elements, meaning that when cortisol activates the GR, it upregulates the expression of its own inhibitor, FKBP5. This creates a fast, intracellular negative feedback loop. In the context of chronic stress, this loop becomes maladaptive.

Persistent GR activation leads to chronically high levels of FKBP5, which perpetuates a state of GR resistance and HPA axis hyperactivity. Certain polymorphisms in the FKBP5 gene have been strongly associated with an increased risk for stress-related psychiatric disorders, highlighting the genetic component of an individual’s vulnerability to stress.

What Are the Systemic Consequences of Cellular Resistance?

The development of GR resistance has profound systemic consequences, primarily through the disinhibition of the inflammatory response. The transcription factor Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) is a master regulator of inflammation, promoting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α).

A primary function of the activated GR is to bind to and inhibit the activity of NF-κB. When GR function is impaired due to resistance, this braking mechanism is released. The resulting overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines creates a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation.

Glucocorticoid receptor resistance, driven by molecular changes like altered receptor isoforms and chaperone protein expression, is the central mechanism through which chronic stress disables its own regulatory feedback loop.

This inflammation is not merely a byproduct of stress; it is an active participant in a destructive feedback cycle. These same cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on the brain to promote further HPA axis activation, induce depressive symptoms, and contribute to neurodegenerative processes.

For example, IL-6 can stimulate the hypothalamus to produce more CRH, further driving the stress response in a system that is already resistant to cortisol’s downstream effects. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of HPA axis hyperactivity, GR resistance, and systemic inflammation that underlies many chronic diseases.

| Stage | HPA Axis Activity | Key Hormonal Markers | Physiological State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 ∞ Alarm |

Hyper-responsive; acute activation |

Elevated cortisol, elevated DHEA |

Heightened alertness, initial adaptation, “wired” feeling. |

| Stage 2 ∞ Resistance |

Sustained hyperactivity, early resistance |

High cortisol, declining DHEA, suppressed T3, suppressed testosterone |

GR resistance begins, inflammation rises, early symptoms of HPG/HPT suppression. |

| Stage 3 ∞ Exhaustion |

Dysregulated; blunted or erratic cortisol rhythm |

Low or dysregulated cortisol, low DHEA, low T3, low testosterone |

Severe GR resistance, high systemic inflammation, clinical hormonal deficiencies, burnout. |

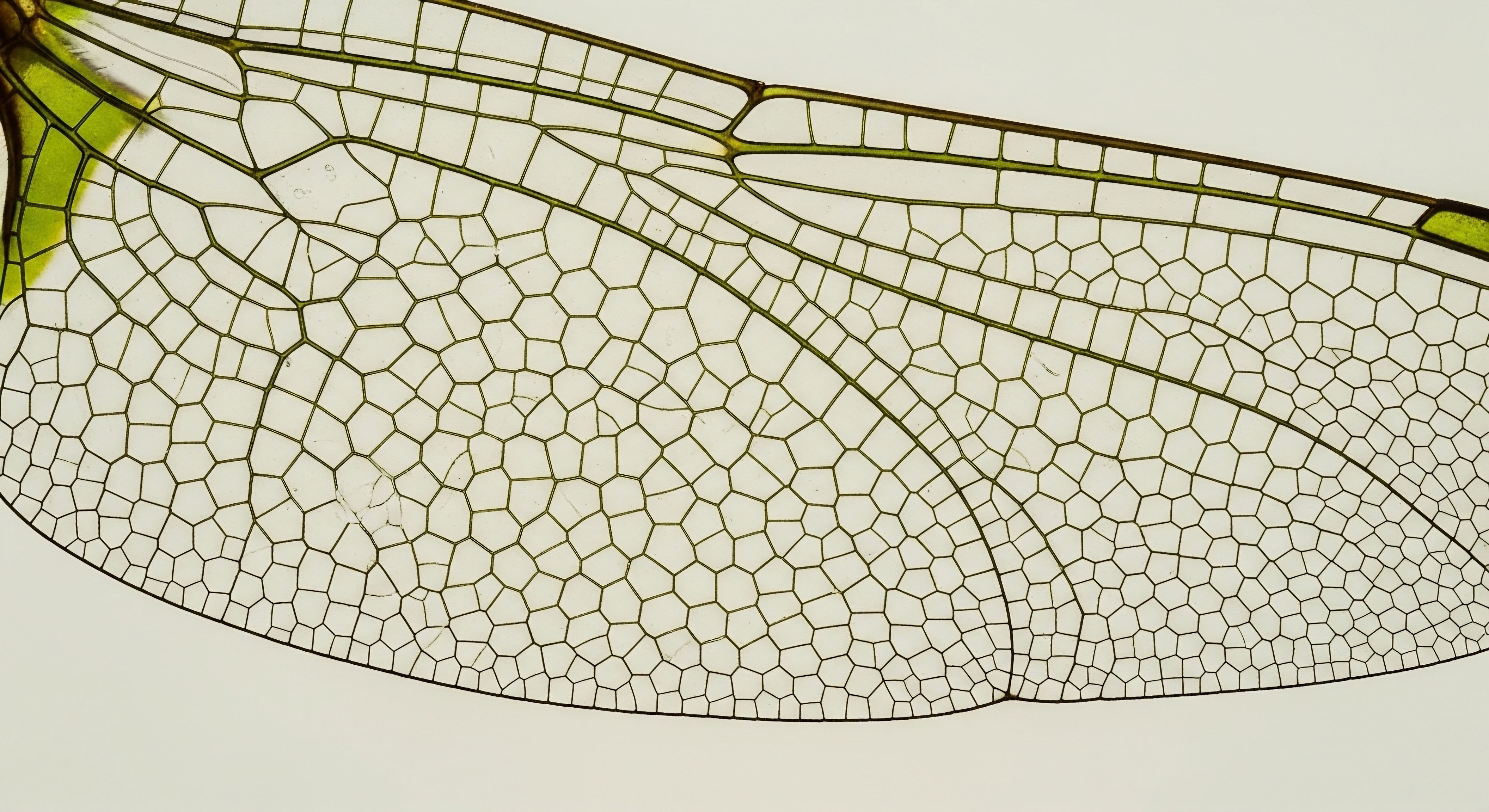

Inter-Axis Crosstalk the Neuroendocrine Cascade

The disinhibition of the HPA axis directly impacts other critical endocrine systems through well-defined neuroendocrine pathways. The relationship between the HPA and HPG axes is a prime example of this crosstalk. CRH, the initiating peptide of the stress cascade, has a direct inhibitory effect on the hypothalamic release of GnRH.

This provides a rapid, central mechanism for shutting down reproductive function during stress. Furthermore, elevated cortisol levels exert suppressive effects at multiple levels of the HPG axis, reducing pituitary sensitivity to GnRH and gonadal sensitivity to LH. The long-term result of this sustained suppression is a state of functional hypogonadism, which may necessitate therapeutic interventions such as TRT for men or targeted hormone support for women to mitigate symptoms and restore physiological balance.

Similarly, the HPA-HPT axis interaction is mediated by several mechanisms. High cortisol levels inhibit the expression of the TRH gene in the hypothalamus and blunt the pituitary’s response to TRH, leading to reduced TSH secretion. At the periphery, cortisol inhibits the activity of the type 1 deiodinase enzyme, which is responsible for converting T4 to the active T3 in tissues like the liver.

This leads to a functional hypothyroidism at the cellular level, even if serum TSH and T4 are within the normal range. The clinical implication is that addressing the underlying stress physiology and HPA axis dysfunction is a necessary prerequisite for effectively restoring thyroid function.

Without recalibrating the HPA axis, simply providing thyroid hormone may be insufficient. These interactions demonstrate that the hormonal consequences of stress are not a collection of isolated events but a predictable, interconnected cascade originating from the dysregulation of the central stress response system.

For individuals seeking to regain function after periods of hormonal suppression, such as men discontinuing TRT or aiming to restore fertility, specific protocols are designed to reactivate the HPG axis. These often include agents like Gonadorelin to stimulate the pituitary, alongside Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) like Clomid or Tamoxifen, which block estrogen feedback at the hypothalamus and pituitary, thereby increasing LH and FSH output.

The use of peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, can also be considered to support the broader endocrine system by stimulating the body’s own production of growth hormone, which can have beneficial effects on metabolism, recovery, and overall cellular health.

References

- Cohen, S. Janicki-Deverts, D. Doyle, W. J. Miller, G. E. Frank, E. Rabin, B. S. & Turner, R. B. (2012). Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (16), 5995 ∞ 5999.

- Drouin, J. Sun, Y. L. Chamberland, M. Gauthier, Y. De Lean, A. Nemer, M. & Schmidt, T. J. (1993). Novel glucocorticoid receptor complex with DNA element of the hormone-repressed POMC gene. The EMBO Journal, 12 (1), 145 ∞ 156.

- Guilliams, T. G. & Edwards, L. (2010). Chronic Stress and the HPA Axis ∞ Clinical Assessment and Therapeutic Considerations. The Standard, 9(2), 1-12.

- Helmreich, D. L. Parfitt, D. B. Lu, X. Y. Akil, H. & Watson, S. J. (2005). Relation between the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during repeated stress. Neuroendocrinology, 81(3), 183 ∞ 192.

- Pariante, C. M. & Miller, A. H. (2001). Glucocorticoid receptors in major depression ∞ relevance to pathophysiology and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(5), 477 ∞ 501.

- Whirledge, S. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2010). Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility. Minerva endocrinologica, 35(2), 109 ∞ 125.

- Silverman, M. N. & Sternberg, E. M. (2012). Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates ∞ from HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1261(1), 55-63.

- Tsigos, C. & Chrousos, G. P. (2002). Hypothalamic ∞ pituitary ∞ adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of psychosomatic research, 53(4), 865-871.

Reflection

The information presented here maps the biological pathways through which the abstract feeling of stress becomes a concrete physiological reality. It connects the lived experience of fatigue, anxiety, and declining vitality to the precise mechanics of cellular communication and hormonal signaling. This knowledge is a powerful tool.

It moves the conversation from one of self-blame or confusion to one of biological understanding. Your symptoms are not a personal failing; they are the predictable outcome of a system operating under prolonged duress. Seeing your body’s response through this lens of systems biology is the foundational step.

Where Does This Understanding Lead?

Recognizing the pattern is the beginning. The journey toward recalibrating these intricate systems is a personal one, guided by the unique data your own body provides. The path forward involves a conscious effort to manage the inputs that activate the stress response and a targeted approach to support the systems that have been compromised.

It is a process of systematically removing the interferences and providing the resources your body needs to restore its own intelligent, self-regulating balance. This knowledge empowers you to ask more precise questions, to seek more targeted assessments, and to become an active, informed participant in the restoration of your own health. The ultimate goal is to move from a state of adaptation to a state of function, reclaiming the energy and vitality that is your biological birthright.