Fundamentals

You may feel a subtle, persistent shift in the landscape of your own vitality. It is an internal dissonance, a feeling that your body’s operational capacity has been quietly down-regulated. This experience, a departure from your baseline of strength and clarity, is a valid and important biological signal.

Your body is communicating a change in its intricate internal economy. At the center of this conversation is a molecule of profound influence, one that orchestrates a symphony of cellular activity. This molecule is testosterone. In the female body, its presence is a quiet strength, a foundational element of vigor, mental acuity, and resilience.

Its role is integral to the architecture of your well-being, governing systems that allow you to build muscle, sustain energy, and maintain cognitive focus. Understanding its function is the first step toward reclaiming the full expression of your physical and mental power.

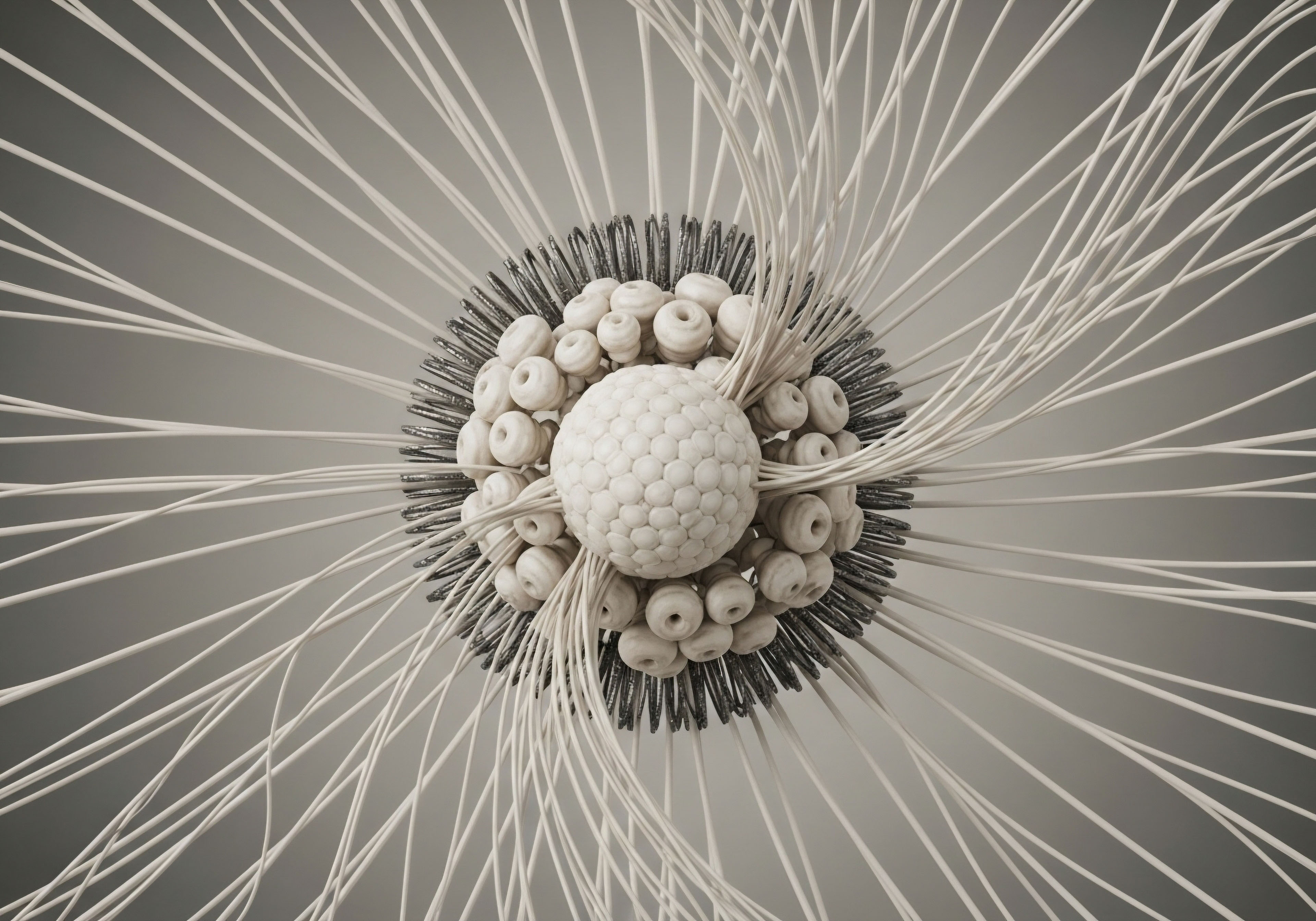

The science of endocrinology provides a map to this internal territory. Testosterone belongs to a class of hormones called androgens, which function as powerful signaling molecules. Within female physiology, the ovaries and adrenal glands produce testosterone, releasing it into the bloodstream to interact with specific receptors in tissues throughout the body.

These receptors are located in the brain, bone, muscle, and fat tissue, illustrating the hormone’s widespread impact. Its actions are direct, influencing cellular processes that govern protein synthesis for muscle maintenance and neurotransmitter function for mood regulation. Concurrently, it serves as a precursor molecule, converted into estrogen in certain tissues, which further extends its biological reach. This dual-action capacity makes it a central regulator of systemic health, a reality that becomes starkly apparent when its availability diminishes.

The gradual decline of testosterone is a key biological event that redefines a woman’s physical and cognitive landscape over time.

The narrative of hormonal aging in women often centers on estrogen and progesterone. This is an incomplete story. Testosterone levels peak in a woman’s twenties and begin a slow, steady descent thereafter. By menopause, circulating levels can be a fraction of their peak.

This decline is a physiological certainty, a predictable consequence of changes in ovarian and adrenal function with age. Events like surgical menopause, where the ovaries are removed, precipitate an abrupt and significant drop in testosterone, making its effects more immediately observable.

The lived experience of this hormonal shift includes a collection of symptoms that are frequently attributed to other causes ∞ a pervasive sluggishness, a notable loss of muscle tone despite consistent effort, and a frustrating fog that clouds mental clarity. These are direct physiological consequences of an endocrine system adapting to a scarcity of one of its key operational assets.

What Is the True Role of Testosterone in the Female Body?

Testosterone’s function in female health extends far beyond reproduction. It is a primary driver of somatic and psychological wellness. Its presence is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the musculoskeletal system, the efficiency of metabolic processes, and the stability of neurological networks. Acknowledging its importance is fundamental to constructing a comprehensive model of female health, one that honors the body’s complex and interconnected biological design.

A Foundation for Physical Strength

The hormone’s most well-understood role is in the maintenance of lean body mass. It directly stimulates protein synthesis in muscle cells, a process that underpins muscular strength, endurance, and the body’s overall metabolic rate. When testosterone is sufficient, the body is primed to build and repair muscle tissue in response to physical activity.

As levels decrease, the balance shifts toward catabolism, the breakdown of tissue, making it progressively harder to maintain, let alone build, muscle mass. This has cascading effects, influencing everything from daily functional strength to the body’s ability to manage glucose effectively.

An Architect of Bone Density

Bone health is another critical domain governed by testosterone. Androgen receptors are abundant in bone cells, where testosterone signaling contributes directly to bone formation and mineralization. It works in concert with estrogen to maintain the dynamic equilibrium of bone remodeling, the continuous process of breaking down old bone and replacing it with new, healthy tissue.

A deficiency in testosterone disrupts this balance, contributing to the accelerated loss of bone density observed during and after the menopausal transition. This creates a vulnerability to osteopenia and osteoporosis, conditions that compromise skeletal strength and increase fracture risk.

| System | Primary Role and Function |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal System |

Stimulates muscle protein synthesis, maintaining lean mass and strength. Contributes to bone mineral density by promoting the activity of bone-forming cells (osteoblasts). |

| Central Nervous System |

Modulates neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine and serotonin, influencing mood, motivation, and cognitive functions like memory and focus. |

| Metabolic System |

Influences fat distribution and insulin sensitivity. Helps regulate the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue, the metabolically active fat surrounding internal organs. |

| Integumentary System (Skin) |

Contributes to skin elasticity and collagen production, supporting the structural integrity and healthy appearance of the skin. |

Intermediate

The consequences of chronically low testosterone are systemic, touching nearly every aspect of a woman’s health. The initial symptoms of fatigue and low libido are merely the surface indications of a deeper biological cascade. When this state is left unaddressed, these functional deficits become embedded in the body’s operating system, leading to a progressive erosion of health across multiple domains.

The process is subtle, an accumulation of small biological compromises that eventually manifest as significant, chronic conditions. Understanding this progression is key to appreciating the profound, long-term impact of androgen insufficiency and the logic behind therapeutic intervention.

The endocrine system functions as a tightly regulated network of feedback loops. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the central command for reproductive hormones, is a prime example. In this system, the brain signals the ovaries to produce hormones. As ovarian function wanes with age, this signaling changes, and testosterone output declines.

This deficit is not an isolated event. It sends ripples across other interconnected systems, notably the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response. A disruption in one axis can destabilize the other, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of hormonal imbalance that can amplify symptoms of stress, anxiety, and fatigue. The body, in essence, loses its ability to efficiently manage both its energy economy and its response to external pressures.

How Does Low Testosterone Alter Metabolic Health?

One of the most significant long-term consequences of unaddressed low testosterone is the degradation of metabolic function. Testosterone exerts a powerful influence on body composition and insulin sensitivity. Its decline is directly correlated with an increase in visceral adipose tissue (VAT), the deep abdominal fat that encases vital organs.

This type of fat is metabolically active and highly inflammatory, secreting signaling molecules called adipokines that promote systemic inflammation and interfere with insulin signaling. This creates a state of insulin resistance, where the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin’s message to absorb glucose from the blood. The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin, leading to hyperinsulinemia. This entire sequence is a well-established pathway toward metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and an elevated risk for cardiovascular disease.

Unaddressed androgen deficiency promotes a metabolic environment conducive to chronic inflammation and insulin resistance.

The loss of muscle mass, a condition known as sarcopenia, further compounds this metabolic dysfunction. Muscle is a primary site for glucose disposal. Less muscle mass means fewer places for the body to store glucose after a meal, contributing to higher blood sugar levels.

The combination of increased inflammatory fat and decreased metabolically active muscle creates a powerful formula for long-term health decline. It is a slow, insidious process that fundamentally alters the body’s ability to manage energy, predisposing it to a host of chronic diseases that define modern morbidity.

- Sarcopenia and Dynapenia ∞ There is a progressive loss of not just muscle mass (sarcopenia) but also muscle strength (dynapenia). This affects mobility, increases the risk of falls and fractures, and lowers the overall metabolic rate, making weight management more challenging.

- Osteoporosis ∞ The persistent lack of androgenic signaling to bone cells accelerates the rate of bone density loss. Over years, this can lead to osteoporosis, a condition characterized by brittle, porous bones that are highly susceptible to fracture, particularly in the hip, spine, and wrist.

- Cardiovascular Strain ∞ The metabolic shifts, including increased visceral fat, insulin resistance, and systemic inflammation, place a chronic strain on the cardiovascular system. This environment promotes the development of atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in the arteries, which is a primary driver of heart attacks and strokes.

- Neurocognitive Decline ∞ The brain is rich in androgen receptors. Chronically low levels of testosterone are associated with a decline in cognitive functions, including memory, processing speed, and executive function. It may also diminish the brain’s resilience, potentially increasing vulnerability to age-related neurodegenerative processes.

The Impact on the Central Nervous System

The neurological and psychological effects of long-term testosterone deficiency are profound. The feelings of low mood, anxiety, and cognitive fog are direct consequences of altered brain chemistry. Testosterone modulates the activity of key neurotransmitter systems, including dopamine, which is central to motivation, reward, and focus, and GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter that promotes calmness.

When testosterone is scarce, this delicate neurochemical balance is disrupted. The result is a brain that is less able to generate feelings of drive and well-being and more susceptible to feelings of anxiety and overwhelm. Over the long term, this can contribute to the development of clinical mood disorders and a persistent sense of diminished mental sharpness, profoundly affecting a person’s quality of life and ability to engage with the world.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of unaddressed female androgen deficiency reveals a complex interplay between endocrine senescence, immunometabolism, and neuroinflammation. The long-term sequelae are a manifestation of systemic failure, where the absence of a key signaling molecule degrades the body’s homeostatic resilience at a cellular and molecular level.

The clinical presentation of fatigue, sarcopenia, and cognitive decline represents the macroscopic outcome of microscopic dysregulation. To truly comprehend the long-term effects, one must examine the molecular mechanisms that connect the loss of androgenic signaling to the pathophysiology of age-related chronic disease. The central thesis is that testosterone is a critical regulator of mitochondrial function and inflammatory signaling, and its deficiency initiates a cascade of events that culminates in accelerated biological aging.

At the heart of this process is the impact of testosterone on cellular energy production. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are exquisitely sensitive to the hormonal environment. Androgens promote mitochondrial biogenesis, the creation of new mitochondria, and enhance the efficiency of the electron transport chain, the primary mechanism for ATP (energy) production.

In a state of androgen deficiency, this support is withdrawn. The result is a decline in both the number and functional capacity of mitochondria, particularly in high-energy-demand tissues like skeletal muscle and the brain. This bioenergetic failure is a core driver of sarcopenia and the pervasive fatigue reported by women with low testosterone. It is a state of cellular energy crisis, where the body lacks the fundamental fuel to perform its physiological duties.

The long-term consequences of androgen deficiency can be understood as a progressive failure of cellular bioenergetics and inflammatory control.

This mitochondrial dysfunction is inextricably linked to another critical process ∞ oxidative stress. Inefficient mitochondria produce an excess of reactive oxygen species (ROS), highly volatile molecules that damage cellular structures, including lipids, proteins, and DNA. Testosterone helps to mitigate this by upregulating the expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes.

When testosterone is absent, this protective mechanism is weakened. The cell is left vulnerable to unchecked oxidative stress, which in turn triggers pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, most notably the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ mitochondrial dysfunction drives inflammation, and inflammation further impairs mitochondrial function.

This state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, sometimes termed “inflammaging,” is a foundational element in nearly every major chronic disease, from atherosclerosis to neurodegeneration.

How Does Androgen Deficiency Affect Neuro-Immune Crosstalk?

The brain is an immune-privileged site, yet it is profoundly influenced by peripheral inflammation. The long-term cognitive and mood-related consequences of low testosterone can be partially explained by its impact on the crosstalk between the endocrine, immune, and central nervous systems. Microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, express androgen receptors.

In a healthy state, testosterone exerts a quiescent effect on these cells, maintaining them in a surveillance mode. In an androgen-deficient state, microglia can become primed to overreact to inflammatory stimuli.

When combined with the systemic inflammation generated by increased visceral adipose tissue and mitochondrial dysfunction, this can lead to a state of chronic neuroinflammation. Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 within the brain parenchyma. These cytokines can disrupt synaptic plasticity, interfere with neurotransmitter synthesis, and are directly toxic to neurons.

This process provides a compelling molecular explanation for the symptoms of “brain fog,” memory impairment, and mood lability. It is a biological state where the brain’s own immune system, lacking the modulatory influence of androgens, contributes to a decline in its own function. This pathway is an active area of research in understanding the heightened risk of cognitive decline and dementia in certain populations.

| Cellular Process | Mechanism of Dysregulation | Systemic Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial Bioenergetics |

Decreased expression of PGC-1α, a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Reduced efficiency of the electron transport chain, leading to lower ATP output. |

Sarcopenia, chronic fatigue, reduced physical performance. |

| Redox Balance |

Downregulation of antioxidant enzymes (e.g. superoxide dismutase). Increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from dysfunctional mitochondria. |

Accelerated cellular aging, increased systemic inflammation. |

| Inflammatory Signaling |

Heightened activation of the NF-κB pathway due to oxidative stress. Increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from adipocytes and immune cells. |

Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, increased cardiovascular risk. |

| Neuro-inflammation |

Priming of microglial cells in the absence of androgenic suppression. Increased pro-inflammatory cytokine levels within the central nervous system. |

Cognitive decline, “brain fog,” mood disorders, potential increase in neurodegenerative risk. |

- Genomic Signaling ∞ Testosterone binds to intracellular androgen receptors, which then translocate to the nucleus and act as transcription factors, directly altering the expression of genes involved in protein synthesis, cell growth, and metabolism.

- Non-Genomic Signaling ∞ Androgens can also initiate rapid signaling cascades through membrane-associated receptors, influencing ion channel activity and activating kinase pathways, which can quickly alter cellular excitability and function, particularly in the nervous system.

- Metabolic Conversion ∞ The enzyme aromatase converts testosterone to estradiol in tissues like fat and brain, allowing testosterone to exert effects through estrogen receptors. Conversely, the enzyme 5-alpha reductase converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a more potent androgen, in tissues like skin and hair follicles.

References

- Davis, S. R. Baber, R. Panay, N. Bitzer, J. Perez, S. C. & Lumsden, M. A. (2019). Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 104(10), 4660 ∞ 4666.

- Traish, A. M. Miner, M. M. Morgentaler, A. & Zitzmann, M. (2011). Testosterone deficiency. American Journal of Medicine, 124(7), 578-587.

- Glaser, R. & Dimitrakakis, C. (2013). Testosterone therapy in women ∞ myths and misconceptions. Maturitas, 74(3), 230 ∞ 234.

- Zitzmann, M. (2020). Testosterone, mood, behaviour and quality of life. Andrology, 8(6), 1598-1605.

- Rastrelli, G. Corona, G. & Maggi, M. (2018). Testosterone and sexual function in men. Maturitas, 112, 46-52.

- Vermeulen, A. Goemaere, S. & Kaufman, J. M. (1999). Testosterone, body composition and aging. The Journal of endocrinological investigation, 22(5 Suppl), 110 ∞ 116.

- Borst, S. E. (2004). The role of testosterone in the decline of muscle, bone, and cognitive function in aging men and women. The Journals of Gerontology Series A ∞ Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59(9), M931-M936.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological grammar for a story your body may be trying to tell. It offers a framework for translating feelings of fatigue or fogginess into a structured conversation about cellular health, metabolic function, and neurological vitality.

The data and mechanisms are a map, a tool to help you locate yourself in your own physiological landscape. This knowledge is the starting point. The path forward involves seeing your own unique biology not as a set of problems to be solved, but as a system to be understood and intelligently supported.

Your personal health narrative is the most important dataset you possess. The ultimate aim is to use this clinical understanding to become a more informed and empowered participant in the lifelong project of stewarding your own well-being.

Glossary

protein synthesis

muscle mass

androgen receptors

osteoporosis

visceral adipose tissue

low testosterone

libido

adipose tissue

systemic inflammation

insulin resistance

sarcopenia

androgen deficiency

neuroinflammation

metabolic syndrome

central nervous system