Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of dissonance within your own body, a collection of symptoms that medical appointments have failed to connect. This experience of fatigue, mood instability, or a general loss of vitality is a valid and frequent starting point for a deeper health inquiry.

The sensation that your internal systems are somehow misaligned is often an accurate perception of a biological reality. At the center of this complex network of communication is a protein of profound significance, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). Your daily dietary choices directly and continuously instruct the behavior of this key regulator. Understanding this dialogue between your plate and your physiology is the first step toward reclaiming your body’s intended function.

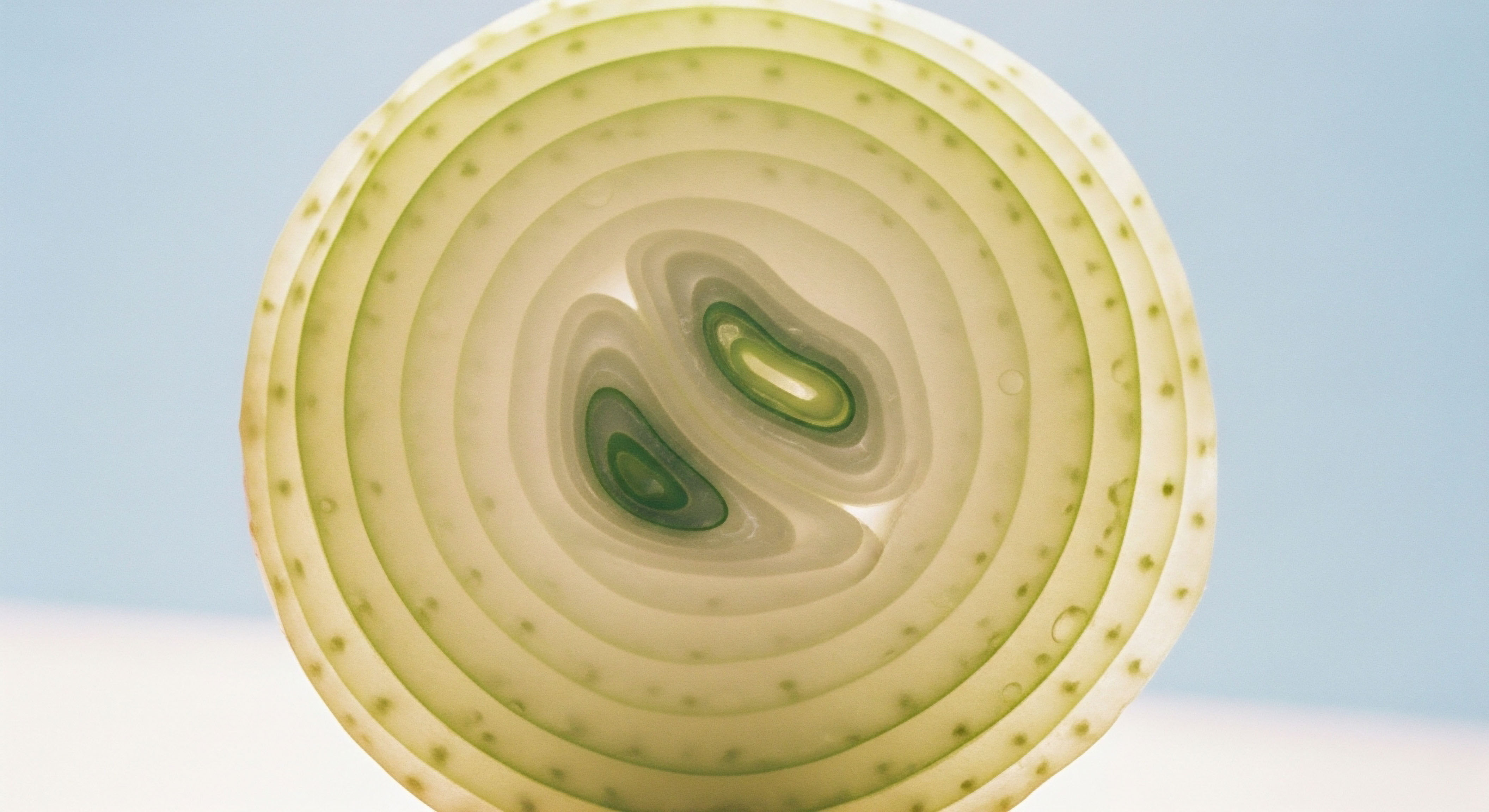

SHBG is synthesized primarily in the liver and functions as the principal transport vehicle for sex hormones, particularly testosterone and estradiol, through the bloodstream. Consider it a highly sophisticated fleet of vehicles, managing the distribution and availability of powerful hormonal messengers.

The number of these vehicles in circulation determines how many hormones are active and available for use by your cells at any given moment. When a hormone is bound to an SHBG molecule, it is biologically inactive, held in reserve. The unbound portion, often referred to as ‘free’ hormone, is what can enter cells and exert its effects.

Therefore, the concentration of SHBG in your blood directly calibrates your body’s hormonal environment. Modulating SHBG levels through diet provides a powerful, non-pharmacological means of adjusting this delicate balance.

The Primary Dietary Signals

Your endocrine system, with the liver at its operational center, is exquisitely sensitive to the nutritional information it receives. The long-term architectural effects of your diet on SHBG levels are governed by a few consistent principles. These signals, sent with every meal, instruct the liver to either increase or decrease the production of SHBG, thereby altering your hormonal landscape over time.

Fiber’s Role in Hormonal Regulation

A diet consistently rich in dietary fiber sends a clear signal to the liver to upregulate SHBG production. Plant-based fibers, particularly lignans found in sources like flax seeds, sesame seeds, and cruciferous vegetables, are potent modulators. These compounds are metabolized by gut bacteria into enterolignans, which have a structural similarity to endogenous estrogens.

This biochemical conversation encourages the liver to produce more SHBG. A higher-fiber diet also tends to improve insulin sensitivity, a key factor in SHBG synthesis. Over years, a commitment to high-fiber eating contributes to a hormonal milieu characterized by higher SHBG, which is associated with a reduced risk for certain hormone-sensitive conditions.

Protein and Fat Composition

The type and amount of protein and fat in your diet also provide durable instructions for SHBG synthesis. Diets with a higher ratio of protein to carbohydrates have been shown to support healthy SHBG levels. Protein provides the essential amino acid building blocks for hepatic protein synthesis and helps stabilize blood sugar, preventing the sharp insulin spikes that can suppress SHBG production.

Similarly, the composition of dietary fats matters. Diets rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, found in olive oil, avocados, and nuts, support overall metabolic health and a balanced inflammatory response, creating an internal environment conducive to optimal liver function and, consequently, stable SHBG levels. Conversely, long-term consumption of diets high in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates can contribute to insulin resistance and fatty liver, conditions that actively suppress SHBG synthesis.

Dietary choices are not passive acts of consumption; they are active, ongoing instructions that shape the hormonal control systems governing your well-being.

What Is the Direct Consequence of Altered SHBG Levels?

The immediate and lasting consequence of diet-modulated SHBG is a change in the bioavailable fraction of your sex hormones. If your dietary pattern leads to chronically low SHBG, a greater percentage of your testosterone and estrogen will be in a free, active state.

While this might seem beneficial, particularly for testosterone, it can disrupt the delicate feedback loops of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Chronically suppressed SHBG is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, indicating a systemic dysfunction that extends far beyond hormone levels alone.

Conversely, a dietary pattern that elevates SHBG will reduce the amount of free hormones. This can be protective in some contexts but may lead to symptoms of hormone deficiency if SHBG levels become excessively high. The objective is a balanced, optimal level of SHBG, achieved through a sustainable, whole-foods-based dietary architecture.

| Dietary Pattern | Primary Mechanism | Expected Long-Term SHBG Trend |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fiber, Plant-Rich | Improved insulin sensitivity, high intake of lignans. | Increase |

| High-Protein, Moderate Carbohydrate | Stabilized blood glucose, reduced insulin spikes. | Stabilize or Increase |

| High in Refined Carbohydrates & Saturated Fat | Promotes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. | Decrease |

| Caloric Restriction / Weight Loss | Improved insulin sensitivity, reduced liver fat. | Increase |

Intermediate

The dialogue between diet and SHBG is orchestrated within the liver, your body’s primary metabolic command center. The long-term effects of your nutritional strategy are the cumulative result of molecular signals that influence gene expression. Specifically, the production of SHBG is governed by a gene whose activity is exquisitely sensitive to the hormone insulin.

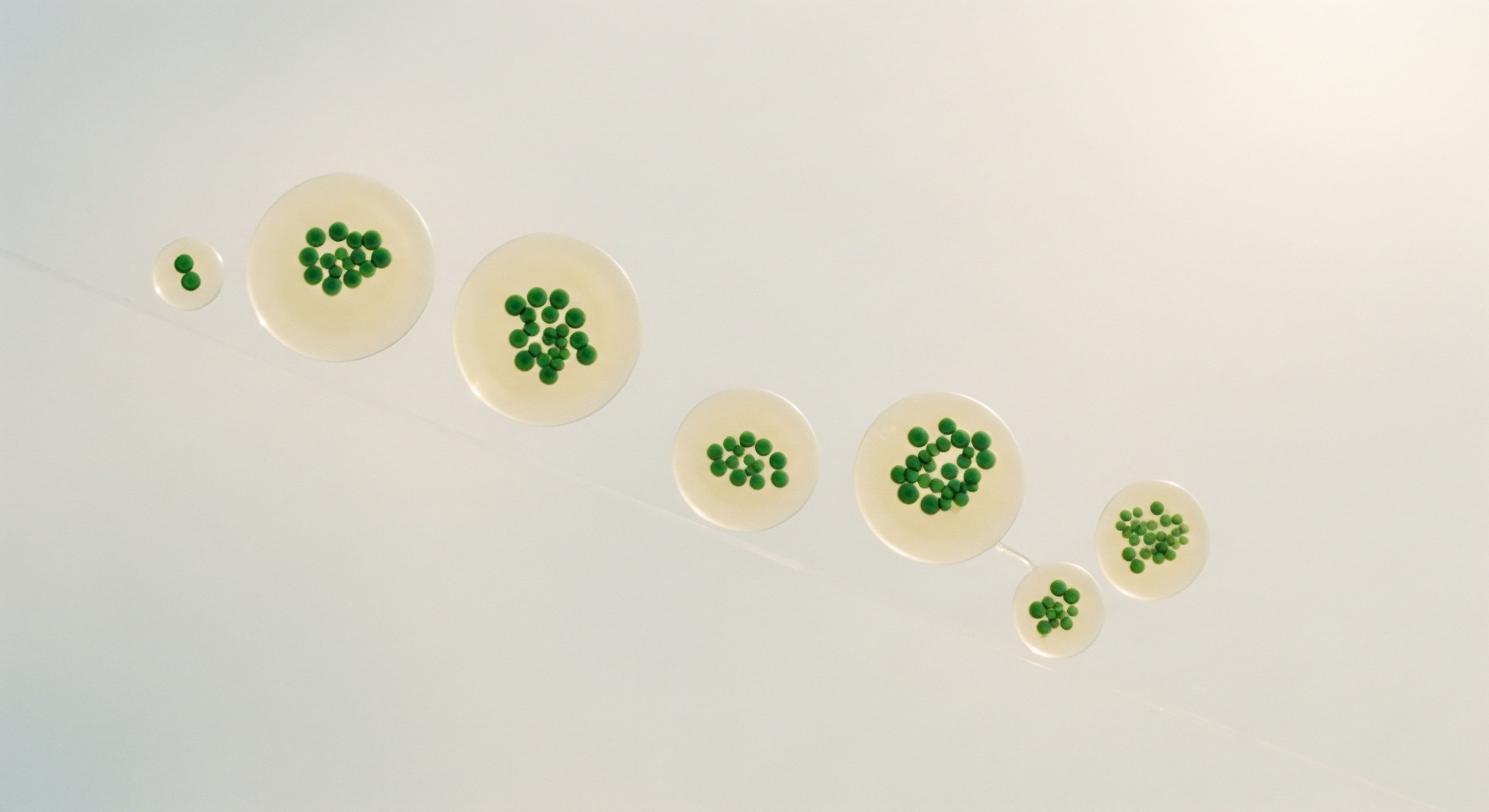

A diet high in refined carbohydrates and sugars triggers significant, rapid releases of insulin from the pancreas. This flood of insulin travels to the liver and directly suppresses the transcription of the SHBG gene. Over months and years, this repeated suppression establishes a new baseline of lower SHBG production. This mechanism is a central reason why chronically low SHBG is considered a powerful predictive marker for the development of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

This process creates a self-perpetuating cycle. Low SHBG means more free testosterone and estradiol are available. The body’s endocrine system, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, senses this higher level of free hormone activity. In response, it may downregulate its own production of stimulating hormones like Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) in an attempt to restore balance.

This complex feedback can lead to a state where total testosterone levels may appear normal or even low on a lab report, yet the underlying issue is a systemic metabolic dysregulation initiated by diet. Addressing the insulin resistance through dietary modification is therefore the foundational therapeutic action.

How Does Weight Loss Affect SHBG Dynamics?

Adipose tissue, or body fat, is an active endocrine organ. It produces inflammatory cytokines and contributes to the state of systemic insulin resistance that suppresses SHBG. Therefore, one of the most potent long-term modulators of SHBG is weight management.

The reduction of excess body fat, particularly visceral fat surrounding the organs, alleviates the chronic inflammatory state and dramatically improves insulin sensitivity. This removes the suppressive brake on the SHBG gene in the liver, allowing for its increased expression and a subsequent rise in circulating SHBG levels.

This effect is so consistent that rising SHBG is a reliable biomarker of improving metabolic health during a weight loss phase. Studies have shown that both high-protein and high-carbohydrate weight loss diets can lead to significant increases in SHBG, suggesting that the caloric deficit and subsequent fat loss are the primary drivers of this improvement.

Modifying SHBG through diet is a process of recalibrating the body’s core metabolic signaling pathways.

Nutrient-Specific Interventions for SHBG Modulation

Beyond macronutrient ratios and overall caloric intake, specific micronutrients and phytonutrients exert considerable influence over SHBG levels when consumed consistently over time. These compounds offer a more targeted approach to dietary modulation.

- Lignans and Isoflavones ∞ These phytoestrogenic compounds, abundant in flaxseed, sesame seeds, soy, and legumes, are powerful upregulators of SHBG. After ingestion, they are converted by the gut microbiome into enterodiol and enterolactone, which directly stimulate SHBG synthesis in the liver. A long-term dietary pattern rich in these foods can lead to clinically significant increases in SHBG.

- Boron ∞ This trace mineral, found in foods like raisins, almonds, and avocados, has been shown in some studies to decrease SHBG levels. It appears to interfere with the binding of hormones to SHBG, thereby increasing the concentration of free testosterone. The long-term implications of consistent boron supplementation are still being investigated, but it represents a targeted nutritional tool for specific hormonal objectives.

- Magnesium ∞ This essential mineral is a cofactor in hundreds of enzymatic reactions, including those involved in insulin signaling. Adequate magnesium status is critical for maintaining insulin sensitivity. A diet deficient in magnesium can contribute to insulin resistance, which in turn suppresses SHBG. Ensuring sufficient intake through foods like leafy greens, nuts, and seeds provides foundational support for healthy SHBG production.

- Nettle Root (Urtica dioica) ∞ Traditionally used for prostate health, compounds within nettle root have been found to bind to SHBG, occupying binding sites. This action can theoretically increase the levels of free, unbound hormones. Its long-term use in dietary protocols is aimed at competitively inhibiting SHBG’s binding activity rather than altering its production.

The Hormonal Free Fraction a Clinical Perspective

The ultimate goal of modulating SHBG is to optimize the ‘free hormone hypothesis,’ which posits that the biological activity of a hormone is dictated by its unbound concentration. A common clinical scenario is a male patient with symptoms of hypogonadism (fatigue, low libido) but a total testosterone level within the normal reference range.

A deeper look often reveals a very high SHBG level, resulting in a low free testosterone concentration. His symptoms are real because the amount of hormone available to his cells is insufficient. A long-term dietary strategy focused on slightly lowering SHBG, perhaps through adjustments in fiber or inclusion of boron-rich foods, could be a primary therapeutic intervention.

Conversely, in a female patient with conditions related to estrogen excess, a diet designed to raise SHBG can be a powerful tool to bind more estrogen and reduce its proliferative signals.

| SHBG Level | Associated Dietary Patterns | Potential Long-Term Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Chronically Low | High in refined carbohydrates, low in fiber, high in saturated fat. | Increased risk of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain hormonal cancers. |

| Optimal / Balanced | Whole foods-based, adequate protein and fiber, healthy fats, stable body weight. | Improved insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation, balanced sex hormone activity, metabolic resilience. |

| Chronically High | Very high fiber intake, very low fat, potentially excessive caloric restriction. | May lead to symptoms of hormone deficiency (low libido, fatigue, bone density issues) due to excessively low free hormone levels. |

Academic

The regulation of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin extends beyond simple macronutrient partitioning into the domain of molecular endocrinology and transcriptional control. The synthesis of SHBG is almost exclusively a hepatic process, governed by the expression of the SHBG gene.

The primary transcriptional regulator of this gene is Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4-alpha (HNF-4α), a master controller of liver-specific gene expression. The long-term metabolic state of the individual, as dictated by diet, directly modulates the activity of HNF-4α.

In states of insulin sensitivity, characterized by a diet rich in complex carbohydrates, fiber, and lean protein, HNF-4α is permitted to bind effectively to the promoter region of the SHBG gene, driving robust transcription. This results in the healthy, baseline levels of SHBG associated with metabolic wellness.

Conversely, a diet that induces a state of hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia initiates a cascade that suppresses HNF-4α activity. Elevated insulin levels promote the phosphorylation and activation of downstream signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway. This cascade ultimately interferes with the ability of HNF-4α to bind to its target DNA sequence on the SHBG gene.

Furthermore, high intracellular glucose levels can lead to the O-GlcNAcylation of HNF-4α, a post-translational modification that also inhibits its transcriptional activity. The sustained consumption of a diet high in refined sugars and processed foods thus establishes a durable epigenetic and transcriptional suppression of SHBG synthesis, providing a direct molecular link between diet, SHBG levels, and long-term metabolic disease risk.

SHBG as an Active Signaling Molecule

The classical view of SHBG presents it as a passive transport protein. A more advanced understanding reveals SHBG as an active signaling molecule in its own right. Specific cell membranes, particularly in adipose and prostate tissues, possess a membrane-bound receptor for SHBG, known as SHBG-R.

When SHBG binds to this receptor, it can initiate intracellular signaling cascades, most notably through the activation of adenylyl cyclase and the generation of cyclic AMP (cAMP). This signaling is independent of the hormone it may or may not be carrying.

Research has demonstrated that SHBG binding to macrophages and adipocytes can exert direct anti-inflammatory and lipolytic effects. It appears to suppress inflammatory responses and reduce lipid accumulation in these cells, which are key processes in the pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome.

This evidence reframes the long-term benefit of a diet that supports healthy SHBG levels. Such a diet does more than just balance free hormone concentrations; it promotes the production of a protein that actively participates in reducing systemic inflammation and improving lipid metabolism.

The protective association between high SHBG and reduced risk of metabolic syndrome is therefore a dual mechanism ∞ a direct effect of SHBG signaling on fat and immune cells, and an indirect effect as a reliable biomarker of hepatic insulin sensitivity. A diet that nurtures the liver’s ability to produce SHBG is one that simultaneously combats the foundational pathologies of metabolic disease.

The long-term dietary modulation of SHBG is a strategic intervention into the transcriptional control of hepatic function and the systemic inflammatory tone.

What Are the Systemic Effects of Chronic SHBG Suppression?

A chronically suppressed SHBG level, driven by years of a high-glycemic, low-fiber diet, has profound and far-reaching consequences for systemic health. The resulting state of functional hyperandrogenism (in women) or altered testosterone-to-estrogen ratios (in men) is just one aspect. The low SHBG level is a proxy for several underlying pathologies:

- Hepatic Steatosis ∞ The same metabolic conditions (hyperinsulinemia) that suppress SHBG also promote the de novo lipogenesis in the liver, leading to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD further impairs the liver’s metabolic functions, exacerbating the cycle.

- Adipose Tissue Dysfunction ∞ Low SHBG is strongly correlated with visceral adiposity. This type of fat is highly inflammatory, releasing cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6 that promote systemic insulin resistance, further suppressing SHBG in a vicious feedback loop. The anti-inflammatory effects of SHBG signaling are lost in this environment.

- Cardiovascular Risk ∞ The constellation of factors associated with low SHBG ∞ insulin resistance, dyslipidemia (high triglycerides, low HDL-C), and inflammation ∞ are all primary risk factors for the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Low SHBG is an independent predictor of future cardiovascular events.

Therefore, a dietary strategy aimed at raising and optimizing SHBG is, in effect, a strategy aimed at reversing the root causes of the most common chronic diseases of modern society. It is a clinical approach that views a single biomarker as an integrated reflection of hepatic health, insulin sensitivity, and systemic inflammation.

References

- Braga-Neto, MB, et al. “Long-Term Effects of a Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing High Protein or High Carbohydrate Weight Loss Diets on Testosterone, SHBG, Erectile and Urinary Function in Overweight and Obese Men.” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 1, 2017, e0169929.

- Mohammadi, Maryam, et al. “The relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and plasma level of sex hormone-binding globulin.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, vol. 22, 2017, p. 118.

- Saeki, Sho, et al. “Protective Effect of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin against Metabolic Syndrome ∞ In Vitro Evidence Showing Anti-Inflammatory and Lipolytic Effects on Adipocytes and Macrophages.” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 294, no. 8, 2019, pp. 2737-2749.

- “Here’s What 12 Months with The Booster Xt Did to Me (2026 Update) Based on Real Data.” Higher Ed Immigration Portal, 2 Aug. 2025.

- “Best Prostapeak Review (2025) What Real Users Are Saying Tested.” Higher Ed Immigration Portal, 2 Aug. 2025.

Reflection

A Dialogue with Your Biology

The information presented here offers a new framework for viewing your daily meals. Each plate is a set of instructions, a form of biological communication that your body diligently interprets and acts upon over the long term. The numbers on a lab report for SHBG are not merely static data points; they are a reflection of this ongoing dialogue.

They tell a story about your liver’s health, your body’s sensitivity to insulin, and the inflammatory state of your internal environment. Consider your own dietary patterns. What messages have you been sending to your endocrine system? Are your nutritional choices building a foundation of metabolic resilience, or are they contributing to a state of chronic dysfunction?

This knowledge positions you as the primary agent in your own health narrative. The process of modulating your body’s hormonal regulators is an act of profound self-stewardship. It requires consistency, patience, and an attentiveness to the subtle shifts in your own sense of well-being.

The path forward involves translating this clinical science into a personal, sustainable practice. It is a journey of recalibrating your systems from the inside out, using the most powerful tool available to you ∞ your diet.