Fundamentals

You may have arrived here feeling a subtle yet persistent disconnect with your body. Perhaps it manifests as a fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a shift in your moods that feels untethered to your daily life, or changes in your body composition that seem to defy your best efforts with diet and exercise.

These experiences are valid, and they often point toward the intricate communication network within your body known as the endocrine system. This system, a collection of glands that produce hormones, is the silent conductor of your internal orchestra, regulating everything from your energy levels and metabolism to your reproductive health and stress responses. Understanding this system is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

Intermittent fasting, the practice of cycling between periods of eating and voluntary fasting, is a powerful metabolic input that can profoundly influence this hormonal orchestra. The timing of your meals sends potent signals to your body, affecting the release and sensitivity of numerous hormones.

At its core, intermittent fasting introduces a period of rest and repair for your metabolic machinery, which can lead to significant shifts in your hormonal landscape. This is a conversation you are having with your biology, and the language is time.

The Body’s Internal Clock and Hormonal Rhythms

Your body operates on a 24-hour cycle known as the circadian rhythm. This internal clock, located in a part of your brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, governs the release of virtually every hormone. It dictates when you feel sleepy, when you feel alert, and when your metabolic processes are most active.

When you eat is a powerful cue for this clock. Aligning your eating patterns with your natural circadian rhythm can support hormonal balance, while misaligned eating can disrupt it. Intermittent fasting, particularly time-restricted eating that emphasizes an earlier eating window, can help to reinforce these natural rhythms, promoting more robust hormonal signaling.

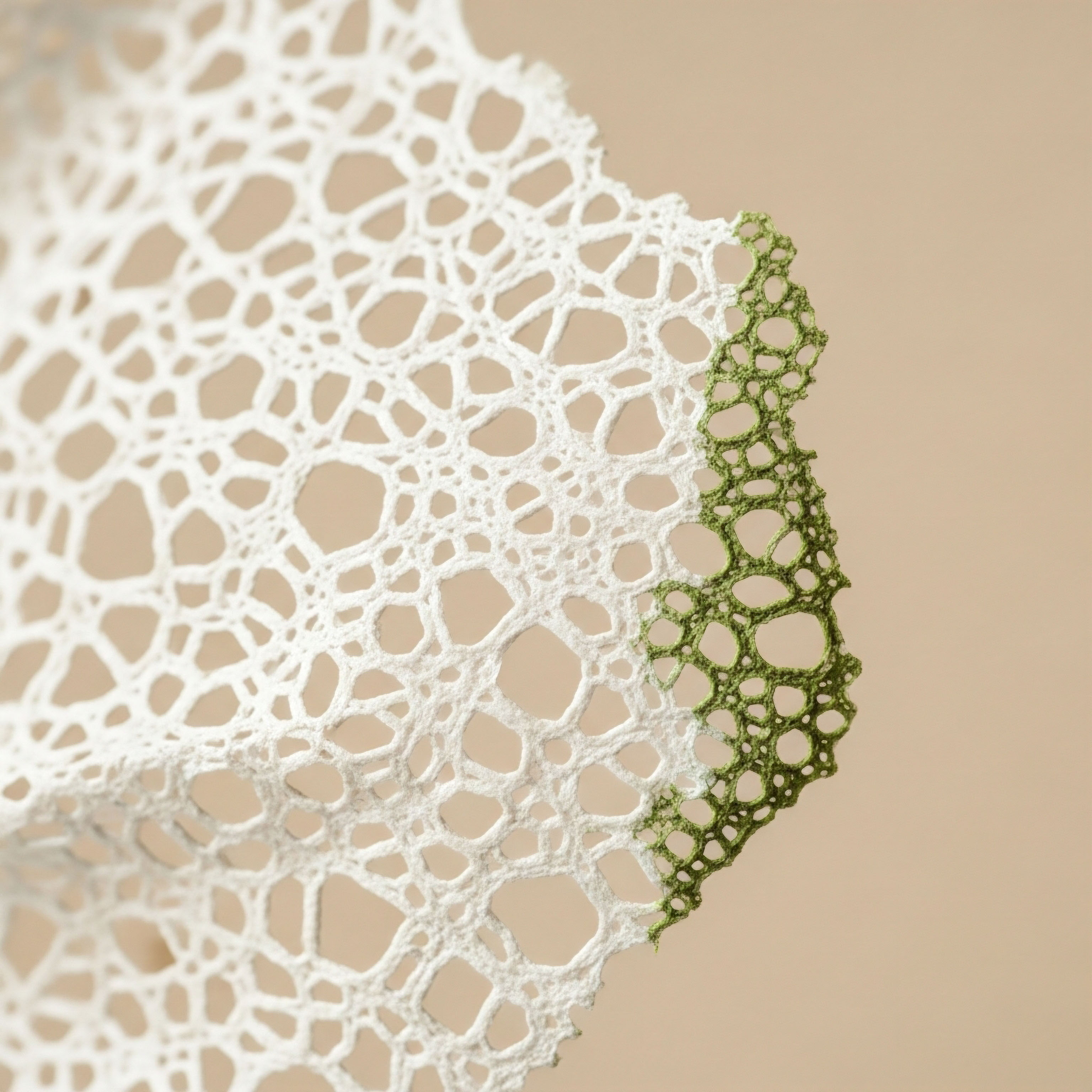

Aligning eating patterns with the body’s natural 24-hour cycle through intermittent fasting can help regulate hormonal communication.

One of the most immediate hormonal responses to fasting is a change in insulin, the hormone responsible for managing blood sugar. When you eat, your pancreas releases insulin to help your cells absorb glucose from your bloodstream for energy. During a fast, insulin levels fall.

This decline in insulin signals your body to start using stored energy, primarily from fat. This metabolic switch is a key benefit of intermittent fasting and has cascading effects on other hormones. Lower insulin levels can improve insulin sensitivity, meaning your cells become more responsive to insulin’s signals. This enhanced sensitivity is a cornerstone of metabolic health and can positively influence other hormonal systems.

Cortisol the Stress Hormone Connection

Cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” also follows a distinct circadian rhythm, typically peaking in the morning to help you wake up and gradually declining throughout the day. While fasting can be a beneficial stressor that promotes cellular resilience, prolonged or improperly managed fasting can sometimes elevate cortisol levels.

For this reason, a personalized approach to intermittent fasting is essential. For some individuals, particularly those already under significant stress, shorter fasting windows or a more gradual introduction to the practice may be more appropriate to avoid overburdening the adrenal glands, which produce cortisol.

The interplay between insulin and cortisol is a delicate one. Chronic stress and high cortisol can contribute to insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin. By improving insulin sensitivity, intermittent fasting can help to mitigate some of the negative metabolic effects of stress. This demonstrates the interconnectedness of your hormonal systems; a change in one area can create a positive ripple effect throughout the entire network.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational concepts, we can now examine the specific ways intermittent fasting protocols influence the complex feedback loops that govern your hormonal health. The endocrine system operates through a series of axes, which are communication pathways between the brain and various glands.

One of the most important of these is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which controls the production of sex hormones. Intermittent fasting can modulate this axis, leading to different outcomes in men and women. The specific type of intermittent fasting you choose, such as time-restricted eating (TRE), alternate-day fasting (ADF), or the 5:2 diet, can also produce distinct hormonal responses.

Time-restricted eating, where you consume all of your daily calories within a specific window (e.g. 8-10 hours), is one of the most studied forms of intermittent fasting. Research suggests that the timing of this window matters.

Early TRE, where the eating window is in the earlier part of the day, appears to offer unique benefits for hormonal balance, likely due to better alignment with the body’s natural circadian rhythms. Let’s explore how these protocols affect male and female hormonal health differently.

Effects on Female Hormonal Balance

For women, the hormonal response to intermittent fasting is particularly nuanced, as the female endocrine system is designed to be highly sensitive to energy availability to support reproductive function. For premenopausal women with obesity, intermittent fasting has shown promising results.

Studies indicate that it can lead to a decrease in androgen levels, such as testosterone, and an increase in sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). SHBG is a protein that binds to sex hormones, regulating their availability in the body. Higher SHBG levels mean less free testosterone circulating, which can be beneficial for conditions characterized by high androgens.

For women with certain health conditions, intermittent fasting can help regulate androgen levels and improve menstrual cycle regularity.

This effect is particularly relevant for women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), a common endocrine disorder characterized by hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and irregular menstrual cycles. By improving insulin sensitivity and reducing androgen levels, intermittent fasting may help to restore menstrual regularity and support fertility in women with PCOS. The table below summarizes some of the observed effects of intermittent fasting on female hormones, particularly in the context of PCOS.

| Hormonal Marker | Observed Effect | Potential Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Total Testosterone |

Decrease |

Reduction in symptoms of hyperandrogenism (e.g. hirsutism, acne) |

| Free Androgen Index (FAI) |

Decrease |

Indicates lower bioavailability of androgens |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) |

Increase |

Binds to and reduces free testosterone, improving hormonal balance |

| Luteinizing Hormone (LH) |

Decrease |

May help to normalize the LH/FSH ratio, which is often elevated in PCOS |

| Insulin |

Decrease |

Improved insulin sensitivity, addressing a core mechanism of PCOS |

Effects on Male Hormonal Balance

In men, the conversation around intermittent fasting and hormones often centers on testosterone. Some studies, particularly in lean, physically active young men, have shown a reduction in total testosterone levels with time-restricted eating. This finding might initially seem concerning, given testosterone’s vital role in male health, including maintaining muscle mass, bone density, and libido.

However, these studies also noted that the decrease in testosterone did not appear to negatively impact muscle mass or strength. This suggests that the body may be adapting in ways that are not fully captured by simply measuring total testosterone levels.

It is also important to consider the population being studied. In overweight or obese men, where testosterone levels may already be suppressed due to higher levels of aromatase (an enzyme that converts testosterone to estrogen in fat tissue), intermittent fasting may have a different effect.

By promoting fat loss, intermittent fasting can reduce aromatase activity, potentially leading to an improvement in the testosterone-to-estrogen ratio. The research in this area is still developing, and more studies are needed to understand the long-term implications for men of different ages and body compositions.

- Lean, Active Men ∞ May experience a decrease in total testosterone, but the clinical significance of this is not yet clear. Muscle mass and strength seem to be preserved.

- Overweight or Obese Men ∞ May experience benefits from weight loss-induced reductions in aromatase activity, which could improve their hormonal profile. Research in this population is less conclusive.

Academic

A sophisticated understanding of the long-term effects of intermittent fasting on hormonal balance requires a systems-biology perspective, moving beyond the direct measurement of hormone levels to explore the intricate web of interactions between metabolic pathways, the gut microbiome, and the body’s internal clock.

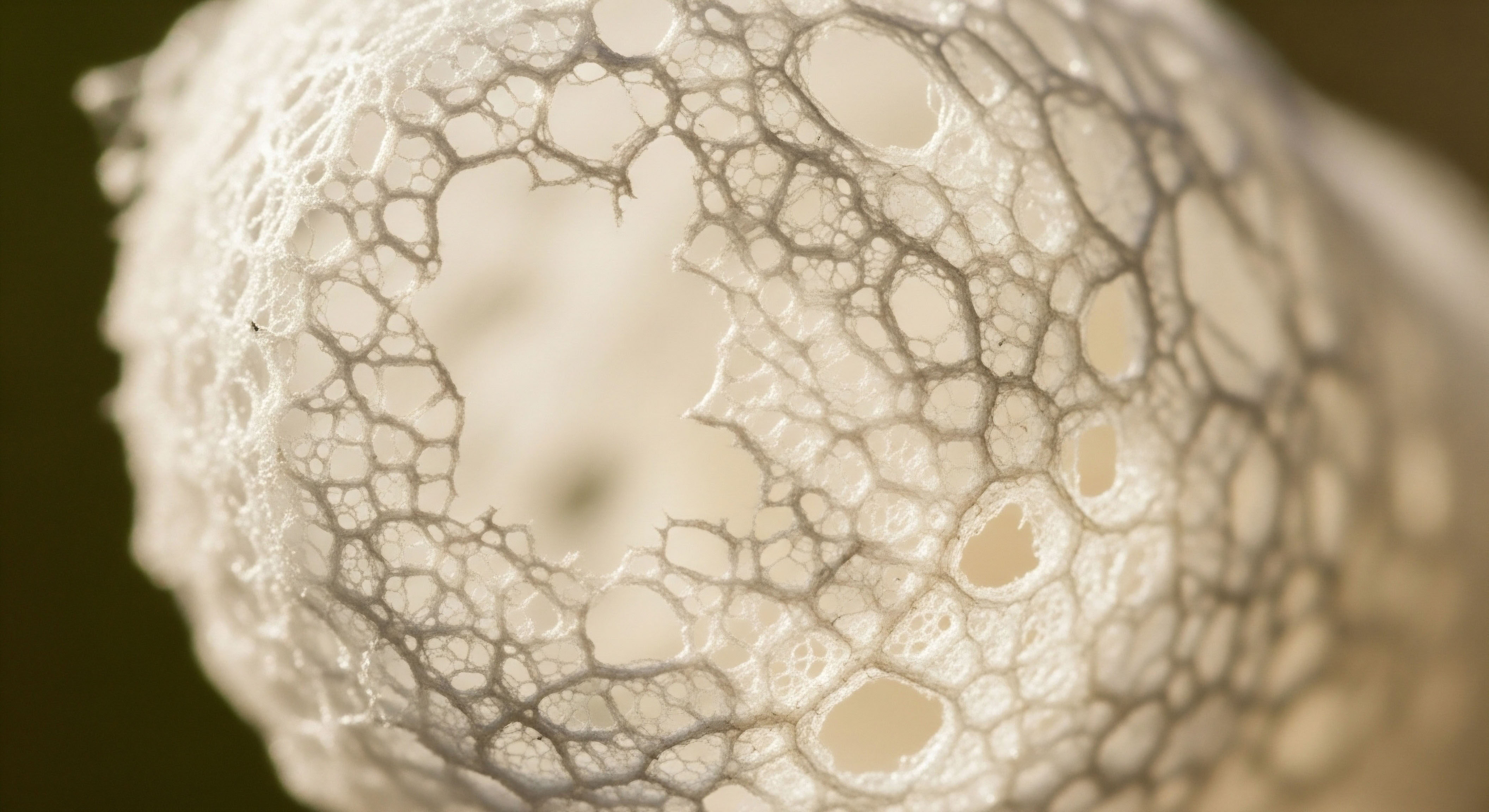

The gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system, is a critical mediator of these effects. The gut microbiome, the vast community of microorganisms residing in your intestines, plays a pivotal role in this axis, and its composition and function can be significantly modulated by fasting.

Intermittent fasting can induce a shift in the gut microbial landscape, often leading to an increase in microbial diversity, which is generally associated with better health. During fasting periods, the gut environment changes, favoring the growth of certain beneficial bacteria.

These microbes can produce a variety of metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have profound effects on host physiology. Butyrate, for example, is an SCFA that serves as a primary energy source for the cells lining the colon and has potent anti-inflammatory properties. By modulating the gut microbiome, intermittent fasting can influence systemic inflammation, which is closely linked to hormonal function.

The Gut Microbiome as an Endocrine Organ

The gut microbiome itself can be viewed as an endocrine organ, capable of producing and regulating hormones. For instance, certain gut bacteria can synthesize neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which can influence mood and behavior. They can also interact with the HPA axis, modulating the stress response.

Furthermore, the gut microbiome plays a role in estrogen metabolism through an enzymatic process involving beta-glucuronidase. By influencing the reabsorption of estrogen, the gut microbiome can affect circulating estrogen levels, which has implications for both men and women.

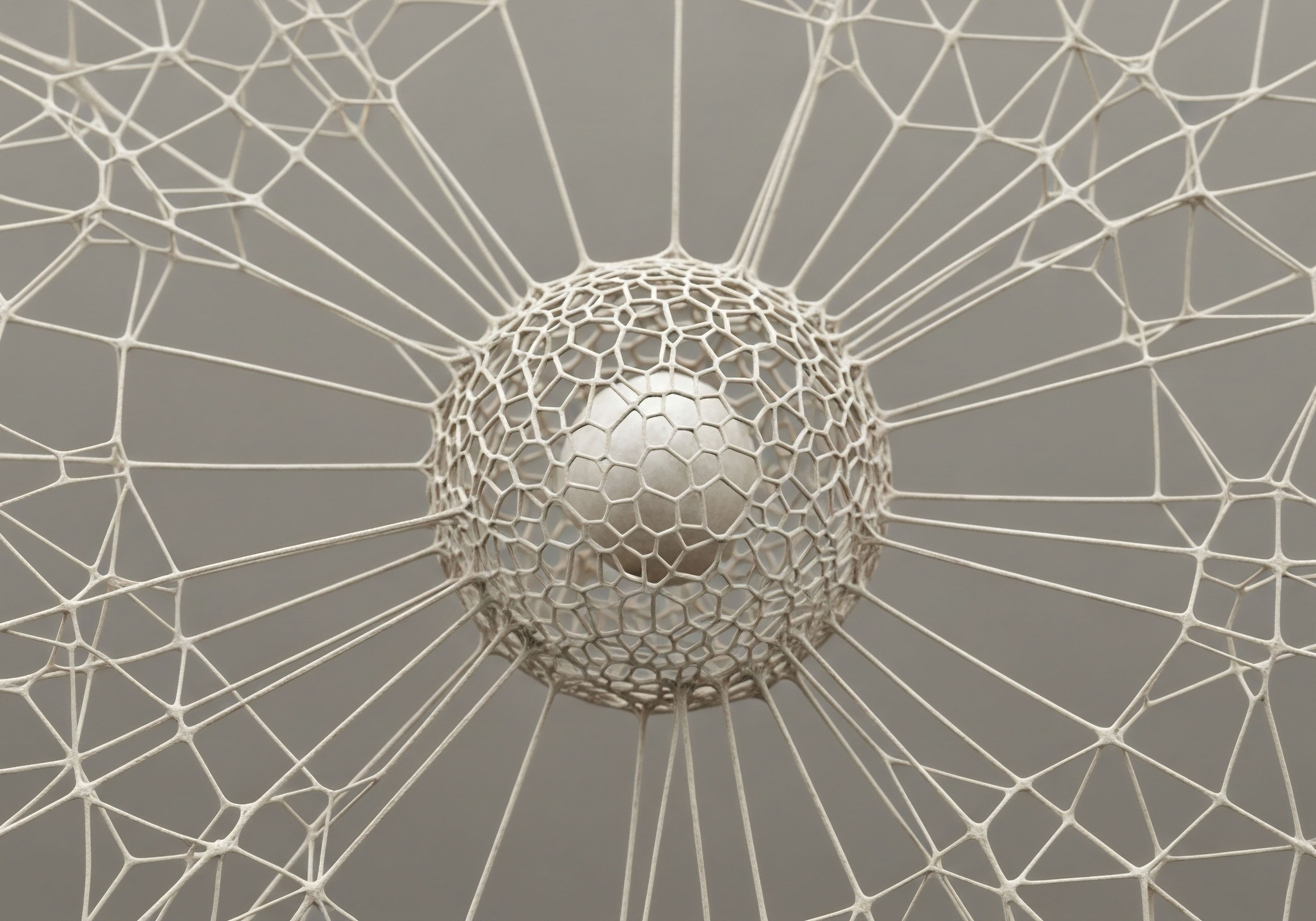

The gut microbiome, profoundly influenced by fasting, acts as a dynamic endocrine organ that modulates hormonal balance throughout the body.

The connection between intermittent fasting, the gut microbiome, and hormonal health is further strengthened by their shared relationship with the circadian rhythm. The gut microbiome exhibits its own diurnal rhythm, with fluctuations in its composition and activity over a 24-hour period.

Aligning eating patterns with the body’s natural light-dark cycle, as is often done with early time-restricted eating, can help to synchronize the host’s circadian clock with the microbial clock. This synchronization can lead to more robust hormonal signaling and improved metabolic health. Disruptions to this alignment, such as late-night eating, can contribute to both circadian misalignment and gut dysbiosis, potentially leading to hormonal imbalances.

| Mechanism | Effect of Intermittent Fasting | Impact on Hormonal Balance |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Diversity |

Increases diversity and richness of the gut microbiome. |

Enhanced resilience of the gut ecosystem, supporting stable hormonal signaling. |

| SCFA Production |

Promotes the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria (e.g. those that produce butyrate). |

Reduces systemic inflammation, improves insulin sensitivity, and supports gut barrier integrity. |

| Circadian Rhythm Synchronization |

Aligns feeding/fasting cycles with the host’s and microbiome’s circadian rhythms. |

Optimizes the timing of hormone release and improves metabolic efficiency. |

| Gut-Brain Axis Communication |

Modulates the production of microbial metabolites that signal to the brain. |

Influences the HPA axis and the regulation of stress hormones like cortisol. |

| Estrogen Metabolism |

Alters the activity of microbial enzymes involved in estrogen metabolism. |

May influence circulating estrogen levels, with implications for both male and female health. |

What Are the Long Term Implications for Hormonal Health?

The long-term effects of intermittent fasting on hormonal balance are likely shaped by these interconnected systems. A sustained practice of intermittent fasting that supports a healthy gut microbiome and reinforces circadian rhythms could lead to lasting improvements in insulin sensitivity, a more balanced stress response, and optimized sex hormone regulation.

For individuals with conditions like PCOS, these changes could translate into long-term management of symptoms and a reduced risk of associated metabolic complications. For men, the long-term effects on testosterone are still being investigated, but a focus on overall metabolic health and body composition is likely to be beneficial for hormonal function.

It is important to acknowledge that the research in this area is ongoing, and individual responses can vary significantly. Factors such as genetics, age, sex, underlying health conditions, and lifestyle all play a role in determining how an individual will respond to intermittent fasting. A personalized approach, guided by an understanding of one’s own biology and, when appropriate, clinical monitoring, is the most effective way to harness the potential benefits of intermittent fasting for long-term hormonal health.

References

- Cienfuegos, Sofia, et al. “Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Reproductive Hormone Levels in Females and Males ∞ A Review of Human Trials.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 11, 2022, p. 2333.

- Al-Zoubi, Mohammad S. et al. “The Impact of Intermittent Fasting on Fertility ∞ A Focus on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Reproductive Outcomes in Women-A Systematic Review.” Metabolic Open, vol. 22, 2024, p. 100341.

- Malinowski, Bartosz, et al. “Intermittent Fasting in Cardiovascular Disorders ∞ An Overview.” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 3, 2019, p. 673.

- Li, C. et al. “The effect of intermittent fasting on polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of Ovarian Research, vol. 14, no. 1, 2021, p. 149.

- Sutton, Elizabeth F. et al. “Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Prediabetic Men.” Cell Metabolism, vol. 27, no. 6, 2018, pp. 1212-1221.e3.

- Cho, Y. et al. “The Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Brain and Cognitive Function.” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 9, 2019, p. 2181.

- Patterson, Ruth E. and Dorothy D. Sears. “Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting.” Annual Review of Nutrition, vol. 37, 2017, pp. 371-393.

- Kim, Min-Jeong, et al. “Effects of Intermittent Fasting on the Circulating Levels and Circadian Rhythms of Hormones.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 36, no. 4, 2021, pp. 745-756.

Reflection

Your Personal Health Blueprint

The information presented here is a map, not a destination. It offers a glimpse into the intricate biological landscape that governs your health and vitality. Your own body is a unique territory, with its own history, its own sensitivities, and its own potential.

The true power of this knowledge lies in its application to your personal health journey. Consider this an invitation to become a more astute observer of your own body, to notice the subtle shifts in your energy, your mood, and your well-being in response to changes you make.

The path to sustained wellness is one of self-discovery and personalization. What works for one person may not work for another. The principles discussed here can serve as a guide, helping you to ask more informed questions and to seek out strategies that are aligned with your unique biology.

This journey is about more than just managing symptoms; it is about cultivating a deeper understanding of your own internal systems so that you can function with clarity, energy, and a profound sense of well-being. Your health is your greatest asset, and you are its most important steward.