Fundamentals

You may feel it as a subtle shift in your daily rhythm, a sense of being out of sync with your own body. This experience, a common narrative in adult health, often finds its roots in the intricate communication network of the endocrine system.

Your hormones are the body’s internal messengers, a sophisticated signaling system that dictates everything from your energy levels and mood to your metabolic rate and reproductive health. Understanding how to support this system is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of vibrant function. A foundational element in this supportive strategy is dietary fiber, a simple carbohydrate with a profound influence on your body’s hormonal conversation.

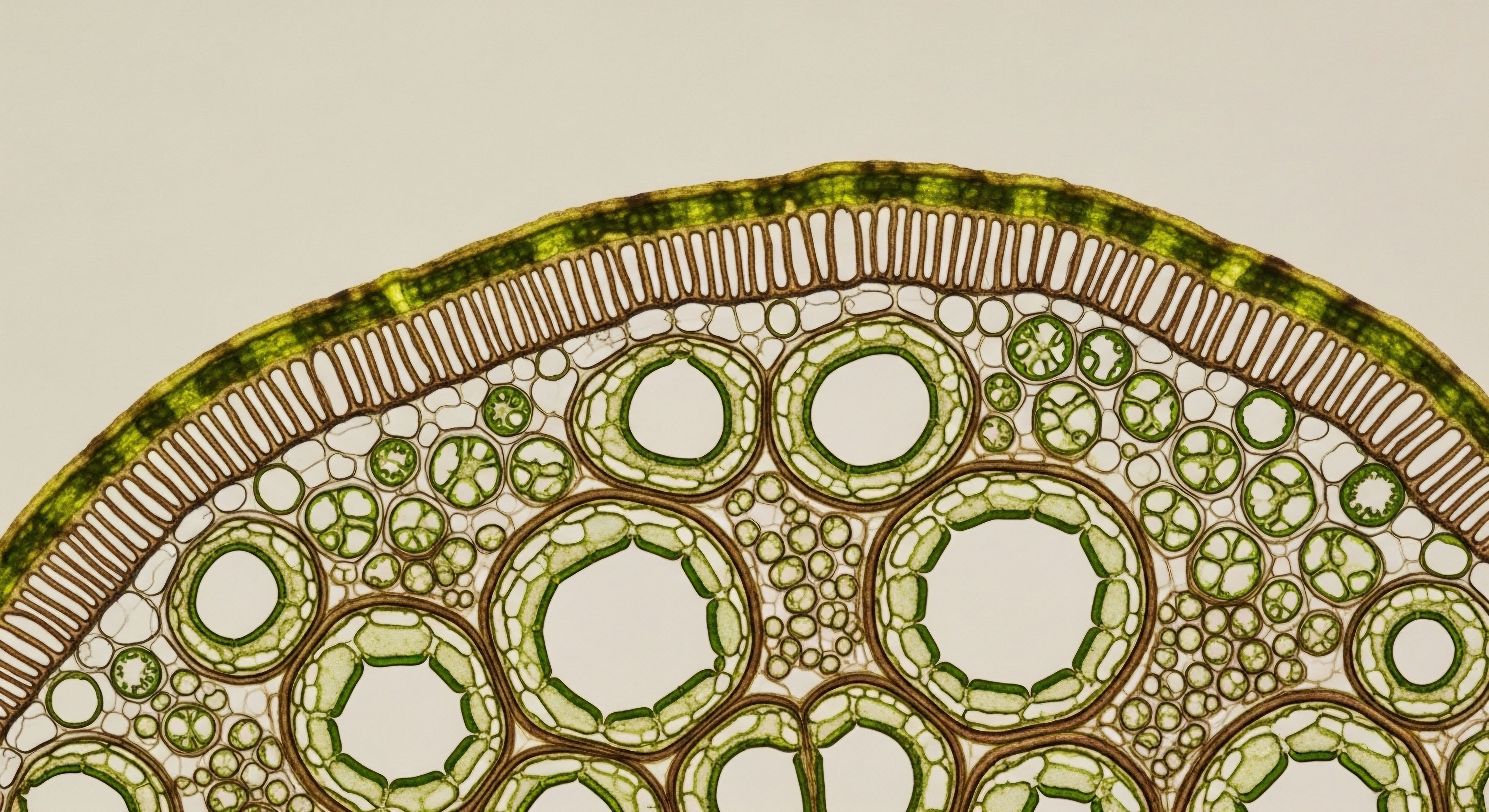

The term fiber describes a category of plant-based carbohydrates that your small intestine cannot digest. This resistance to digestion is precisely where its power lies. Fiber travels through your digestive tract largely intact, acting as a crucial tool for maintaining the health of the entire system. This journey has direct and significant consequences for your hormonal well-being, primarily through two distinct mechanisms of action.

Dietary fiber directly influences hormonal balance by managing blood sugar levels and facilitating the removal of excess hormones from the body.

The Two Faces of Fiber

Dietary fiber is broadly categorized into two main types, each with a unique role in supporting your physiology. Their coordinated action is essential for a well-regulated internal environment.

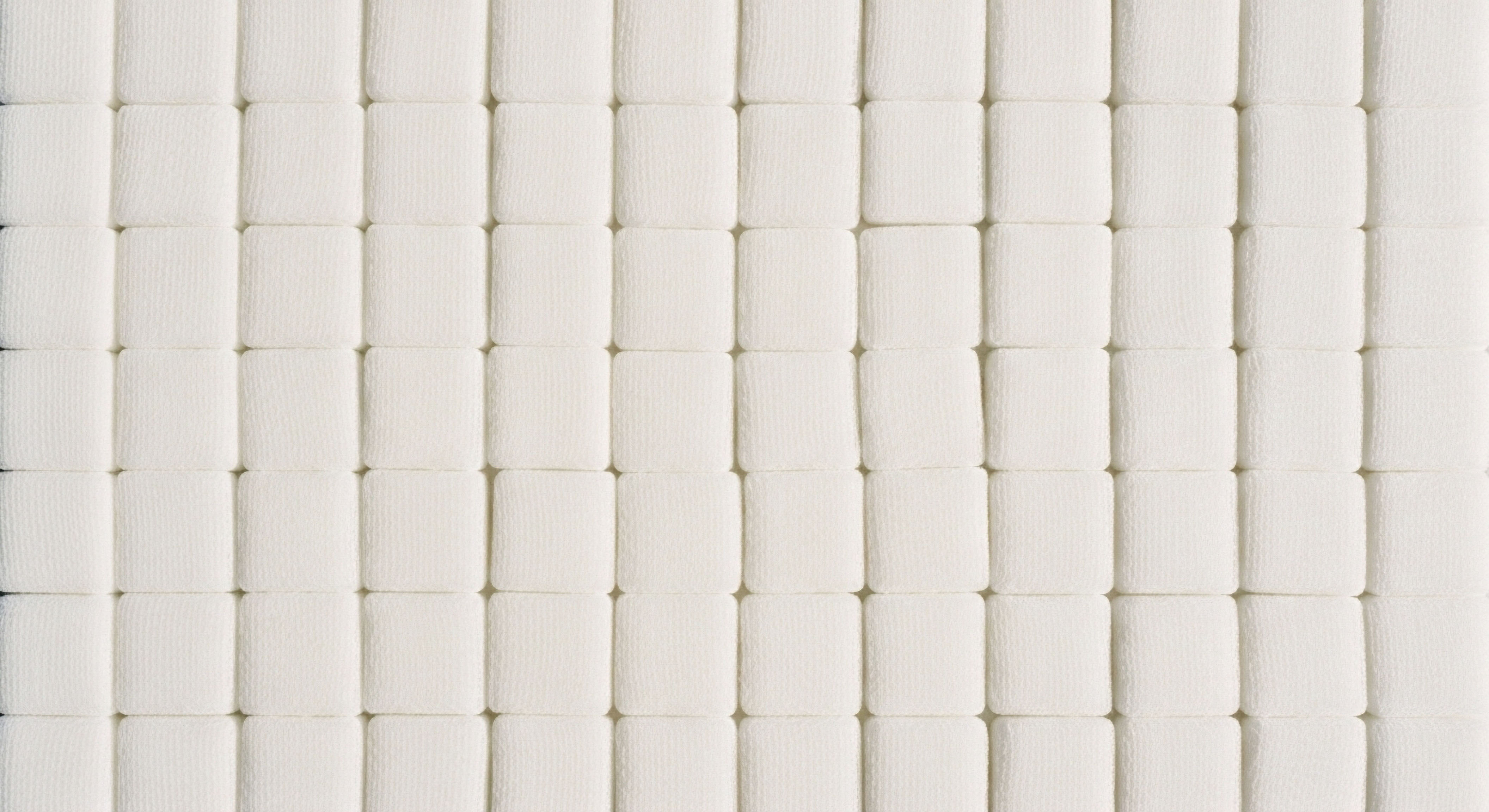

- Soluble Fiber This type dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance in your digestive tract. This gel slows down digestion, which is particularly beneficial for blood sugar control. By moderating the speed at which sugars are absorbed into the bloodstream, soluble fiber helps prevent the sharp spikes in blood glucose that demand a large insulin response. Foods rich in soluble fiber include oats, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, and certain fruits like apples and citrus.

- Insoluble Fiber This type does not dissolve in water. Instead, it adds bulk to the stool, promoting regular bowel movements. This bulking action is critical for efficient waste elimination. Think of it as the digestive system’s broom, sweeping the colon clean. This process is essential for excreting metabolic byproducts, including hormones that have completed their function. You can find insoluble fiber in whole grains, nuts, and vegetables like cauliflower, green beans, and potatoes.

The Estrogen Excretion Pathway

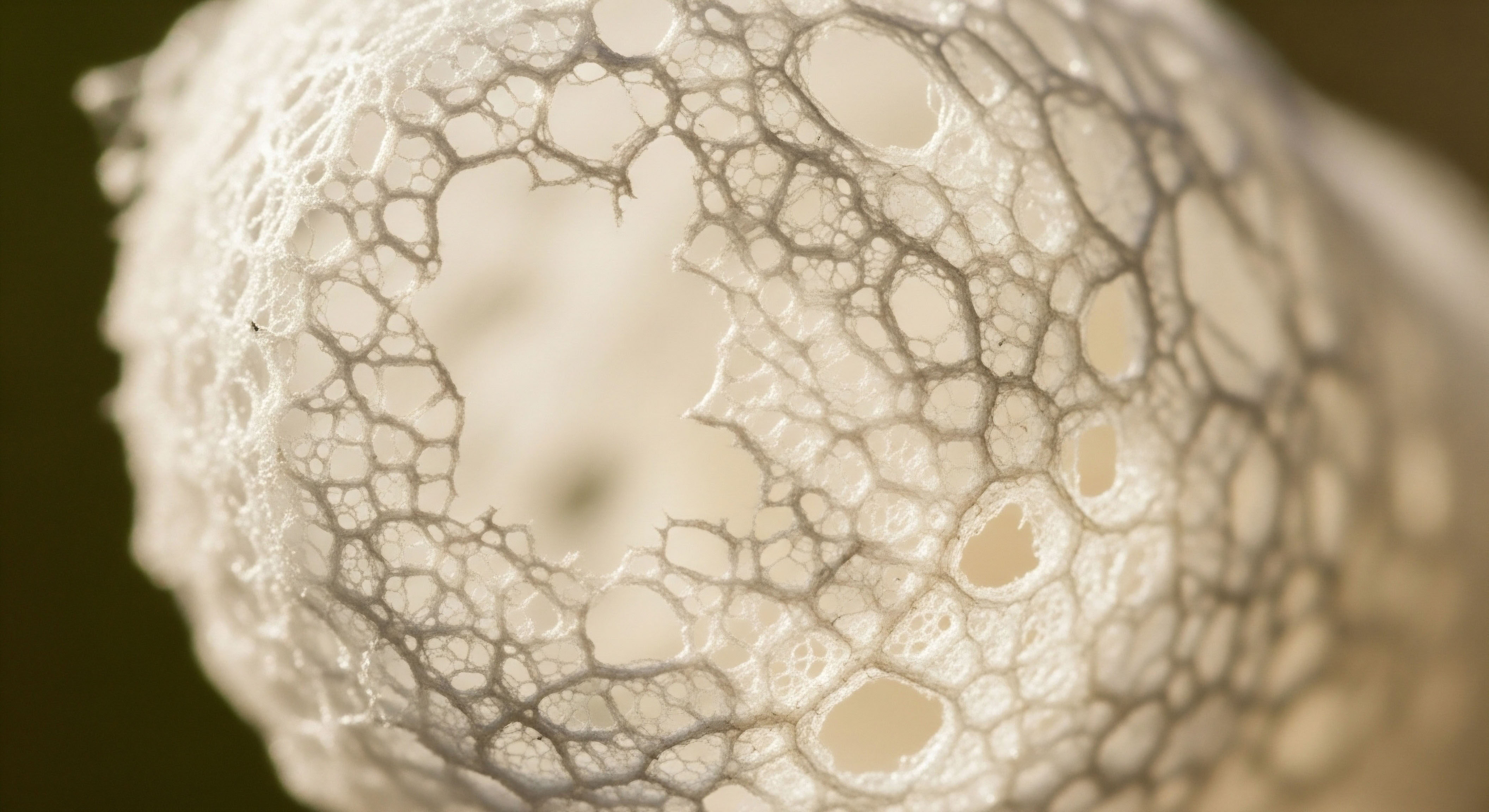

One of the most significant long-term effects of consistent fiber intake on hormonal health involves the regulation of estrogen. Your liver processes hormones, packaging excess amounts for removal from the body via the digestive tract. Here, fiber intake becomes exceptionally important. Fiber binds with this processed estrogen in the gut, ensuring it is carried out of the body with other waste products.

In a low-fiber environment, a portion of this estrogen can be reabsorbed back into circulation through the intestinal wall. This reabsorption contributes to a higher overall estrogen load in the body, a state that can disrupt the delicate balance between estrogen and other hormones like progesterone.

By ensuring adequate fiber intake, you support the body’s natural process of hormonal detoxification, helping to maintain optimal levels over the long term. This mechanism is particularly relevant for reducing the risk of conditions associated with high estrogen levels.

Stabilizing Insulin the Metabolic Foundation

Your hormonal health is inextricably linked to your metabolic function. The hormone insulin, released by the pancreas, is responsible for managing blood sugar levels. A diet that causes frequent, large spikes in blood sugar forces the pancreas to produce high levels of insulin repeatedly. Over time, the body’s cells can become less responsive to insulin’s signals, a condition known as insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance is a precursor to a cascade of hormonal issues. It is linked to higher levels of circulating androgens (like testosterone) in women, disruptions in ovulation, and an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Soluble fiber is a powerful tool for improving insulin sensitivity.

By slowing carbohydrate absorption and promoting a gentler blood sugar curve, it reduces the demand for insulin and helps keep your cells responsive to its signals. This stabilizing effect creates a solid foundation upon which all other hormonal systems can function more effectively, making it a cornerstone of long-term endocrine health.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of fiber’s role reveals a more intricate biological landscape. The long-term influence of fiber on hormonal health is mediated by the vibrant, microscopic ecosystem within your gut, the gut microbiome.

This community of trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes is a dynamic metabolic organ in its own right, directly participating in the regulation of your endocrine system. The food you consume, particularly prebiotic fibers, serves as the primary fuel that shapes the composition and function of this inner world.

The Gut Microbiome the Endocrine Control Center

Your gut is in constant communication with the rest of your body, and hormones are a key part of this dialogue. The gut-hormone axis is a bidirectional pathway where gut microbes can influence the production and metabolism of hormones, and hormones can in turn alter the composition of the gut microbiome.

Prebiotic fibers, which are non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria, are central to this process. As bacteria ferment these fibers, they produce a range of bioactive compounds that have systemic effects.

Among the most important of these compounds are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These molecules are the primary energy source for the cells lining your colon, but their influence extends far beyond the gut.

SCFAs enter the bloodstream and travel throughout the body, where they act as signaling molecules that help regulate inflammation, appetite, and metabolic health. For instance, butyrate has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce systemic inflammation, both of which are critical for maintaining hormonal equilibrium.

Introducing the Estrobolome

Within the gut microbiome is a specialized collection of bacteria known as the estrobolome. These microbes possess the unique ability to produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can effectively “reactivate” estrogens that have been processed by the liver and sent to the gut for excretion. A high level of beta-glucuronidase activity can lead to more estrogen being reabsorbed into the body, increasing circulating levels.

Dietary fiber plays a crucial role in modulating the activity of the estrobolome. Certain types of fiber can help maintain a healthy gut environment that favors a balanced level of beta-glucuronidase activity. This helps ensure that processed estrogens are efficiently excreted rather than reabsorbed, supporting a healthy estrogen balance. This microbial influence is a key mechanism explaining the observed association between higher fiber diets and lower risks of estrogen-dependent conditions.

The composition of your gut microbiome, shaped by fiber intake, directly regulates the metabolism and clearance of key hormones like estrogen.

How Does Fiber Impact Hormone Bioavailability?

Beyond direct excretion, fiber can influence the amount of active hormones circulating in your body by modulating Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). SHBG is a protein produced by the liver that binds to sex hormones, primarily testosterone and estrogen. When a hormone is bound to SHBG, it is inactive and cannot exert its effects on target tissues. Only free, unbound hormones are biologically active.

Studies have shown that diets high in fiber can increase serum concentrations of SHBG. By increasing the number of available binding proteins, a high-fiber diet can effectively reduce the amount of free estrogen and testosterone in circulation. This provides another layer of hormonal regulation, helping to buffer against excesses of these powerful hormones and contributing to a more stable endocrine environment over the long term.

Comparing Fiber Types and Their Hormonal Impact

Different types of fiber have distinct physiological effects that contribute to their overall impact on hormonal health. Understanding these differences allows for a more targeted dietary approach to support specific wellness goals.

| Fiber Type | Primary Mechanism | Key Hormonal Effects | Primary Food Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble Fiber | Forms a gel in the gut, slowing digestion. Fermented by gut bacteria into SCFAs. |

Significantly improves insulin sensitivity by blunting glucose spikes. May lower circulating androgens. Can increase SHBG levels. Supports SCFA production. |

Oats, barley, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, peas, beans, psyllium husk. |

| Insoluble Fiber | Adds bulk to stool, speeding intestinal transit time. |

Promotes efficient excretion of metabolized estrogens, preventing their reabsorption. Reduces transit time, limiting the window for hormone reactivation by the estrobolome. |

Whole wheat flour, wheat bran, nuts, seeds, cauliflower, green beans, potatoes. |

| Resistant Starch | Resists digestion and ferments in the large intestine, acting as a prebiotic. |

Improves insulin sensitivity. May help lower levels of leptin, the satiety hormone, which can become dysregulated in metabolic conditions. Strongly promotes the production of butyrate. |

Green bananas, cooked and cooled potatoes/rice, legumes, whole grains. |

Academic

A sophisticated examination of fiber’s long-term effects on hormonal health requires moving into the realm of clinical research, where the data reveals a more complex and context-dependent picture. While the benefits of fiber for metabolic health and estrogen clearance are well-documented, its influence on the central regulatory system of reproductive function, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, warrants a detailed analysis.

The relationship is not always linear, and understanding the nuances is critical for applying this knowledge effectively in a clinical setting, especially for reproductive-aged women.

Modulation of the HPG Axis a Clinical Perspective

The HPG axis is the command center for reproductive hormones. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary gland to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These gonadotropins then travel to the gonads (ovaries or testes) to stimulate the production of sex hormones like estradiol and progesterone, and to govern processes like ovulation and spermatogenesis.

The system is regulated by a sensitive negative feedback loop, where circulating sex hormones signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to modulate their output.

Prospective cohort studies have provided deep insights into how high dietary fiber intake can influence this delicate axis. The BioCycle Study, a notable investigation following healthy, regularly menstruating women, found that higher fiber consumption was inversely associated with concentrations of estradiol, progesterone, LH, and FSH. This suggests that a high-fiber diet does not just impact hormone clearance in the gut; it appears to exert a systemic effect that reaches the very top of the regulatory chain.

What Are the Implications of Fiber Induced Anovulation?

Perhaps the most striking finding from the BioCycle Study was the positive association between increased fiber intake and the risk of anovulation, which is a cycle where no egg is released. The data indicated that each 5-gram per day increase in total fiber was associated with a nearly 1.8-fold increased risk of experiencing an anovulatory cycle. This effect was even more pronounced with fiber from fruit.

From a mechanistic standpoint, this finding is biologically plausible. The observed reduction in circulating gonadotropins (LH and FSH) and estradiol could lead to insufficient hormonal stimulation to trigger ovulation. The mid-cycle LH surge is the critical event that causes the dominant follicle to rupture and release an egg.

If LH levels are consistently suppressed, this surge may fail to occur. This presents a significant clinical consideration. For a woman experiencing symptoms of estrogen dominance, the estrogen-lowering effect of fiber is beneficial. For a woman seeking to conceive, a diet exceptionally high in fiber could potentially become a confounding factor in her fertility journey.

High dietary fiber intake has been clinically associated with decreased concentrations of key reproductive hormones and a higher probability of anovulation in premenopausal women.

Fiber Intake in the Context of Hormonal Therapies

These findings have direct relevance to the clinical management of patients undergoing hormonal optimization protocols. For instance, a post-menopausal woman on a stable dose of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) who significantly increases her dietary fiber intake might experience a change in her symptoms.

The increased fiber could enhance the excretion of the exogenous estrogen she is taking, potentially lowering its bioavailability and necessitating a dosage adjustment. Similarly, for a man on Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) who is also using an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole to control estrogen conversion, a very high-fiber diet could add another layer of estrogen modulation that needs to be accounted for in his overall protocol.

The data underscores the principle of biochemical individuality. There is no single “optimal” fiber intake for all people at all times. The ideal amount depends on an individual’s specific hormonal milieu, health goals, and clinical context.

A Deeper Look at Fiber’s Systemic Impact

The following table synthesizes data from clinical observations, outlining how different levels of fiber intake might affect key hormonal and metabolic parameters, illustrating the dose-dependent nature of its effects.

| Parameter | Low Fiber Intake (<15g/day) | Moderate Fiber Intake (25-35g/day) | High Fiber Intake (>40g/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Sensitivity |

Reduced; associated with higher risk of insulin resistance and blood sugar dysregulation. |

Improved; associated with stable blood glucose and reduced insulin spikes. |

Generally high; may offer enhanced metabolic benefits. |

| Estrogen Clearance |

Inefficient; may lead to estrogen reabsorption and higher circulating levels. |

Efficient; supports healthy detoxification pathways and hormonal balance. |

Very efficient; significantly lowers circulating estrogen levels. |

| SHBG Levels |

Tend to be lower, increasing free hormone concentrations. |

Tend to be higher, helping to regulate free hormone bioavailability. |

May be significantly elevated, further reducing free hormone levels. |

| Ovulatory Function (Premenopausal) |

Generally unaffected by this specific variable, though metabolic issues can cause anovulation. |

Generally supported by stable metabolic health. |

Potential for increased risk of anovulation due to suppression of gonadotropins and estradiol. |

References

- Gaskins, Audrey J. et al. “Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function ∞ the BioCycle Study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 90, no. 4, 2009, pp. 1061-1069.

- Farvid, Maryam S. et al. “Dietary Fiber Intake in Young Adults and Breast Cancer Risk.” Pediatrics, vol. 137, no. 3, 2016.

- “The Importance of Fiber in Gut Health and Hormonal Balance.” Food Revolution Network, 24 Mar. 2023.

- “Why Fiber is crucial for balancing Hormones.” REVIVO Wellness Resort, 27 Apr. 2022.

- Slavin, Joanne L. “Effects of Dietary Fiber and Its Components on Metabolic Health.” Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 4, 2013, pp. 1417-1435.

Reflection

Listening to Your Body’s Internal Dialogue

The information presented here provides a map of the biological mechanisms connecting a fundamental dietary choice to the complex world of your endocrine system. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting the conversation from one of passive symptoms to one of active support.

Your body is in a constant state of communication with itself, and your daily choices are a primary input into that dialogue. The way you feel day-to-day ∞ your energy, your mood, your resilience ∞ is the output.

Consider your own unique context. Where are you in your life’s journey? Are your goals centered on metabolic health, fertility, or navigating the changes of midlife? The science shows us that the “right” approach is one that is tuned to your specific physiology and personal objectives. The data on fiber’s dose-dependent effects on the HPG axis is a clear illustration of this principle. What is optimally supportive for one person may require adjustment for another.

This understanding is the starting point. It empowers you to ask more precise questions and to become a more active partner in your own wellness. The path to reclaiming and sustaining vitality is one of continuous learning and recalibration, a journey of aligning your external choices with your internal biological needs. This is the foundation of a truly personalized approach to health, one that is built on a deep respect for the intricate systems that govern your well-being.

Glossary

dietary fiber

soluble fiber

blood sugar

hormonal health

fiber intake

managing blood sugar levels

insulin sensitivity

gut microbiome

gut-hormone axis

short-chain fatty acids

metabolic health

the estrobolome

estrobolome

sex hormone-binding globulin

luteinizing hormone

hpg axis

high dietary fiber intake

anovulation