Fundamentals

You may feel a sense of confusion when it comes to dietary fats, and that is entirely understandable. For decades, a low-fat approach was presented as the single path to health. Today, you are presented with a different, more complex picture.

The reality of our biology is that dietary fats are not merely a source of calories; they are fundamental building blocks for the very communication network that runs your body ∞ the endocrine system. Your hormones, the chemical messengers that govern everything from your mood and energy levels to your reproductive health, are synthesized directly from components of the fats and cholesterol you consume. Making informed choices about dietary fat is a foundational step in managing your hormonal health.

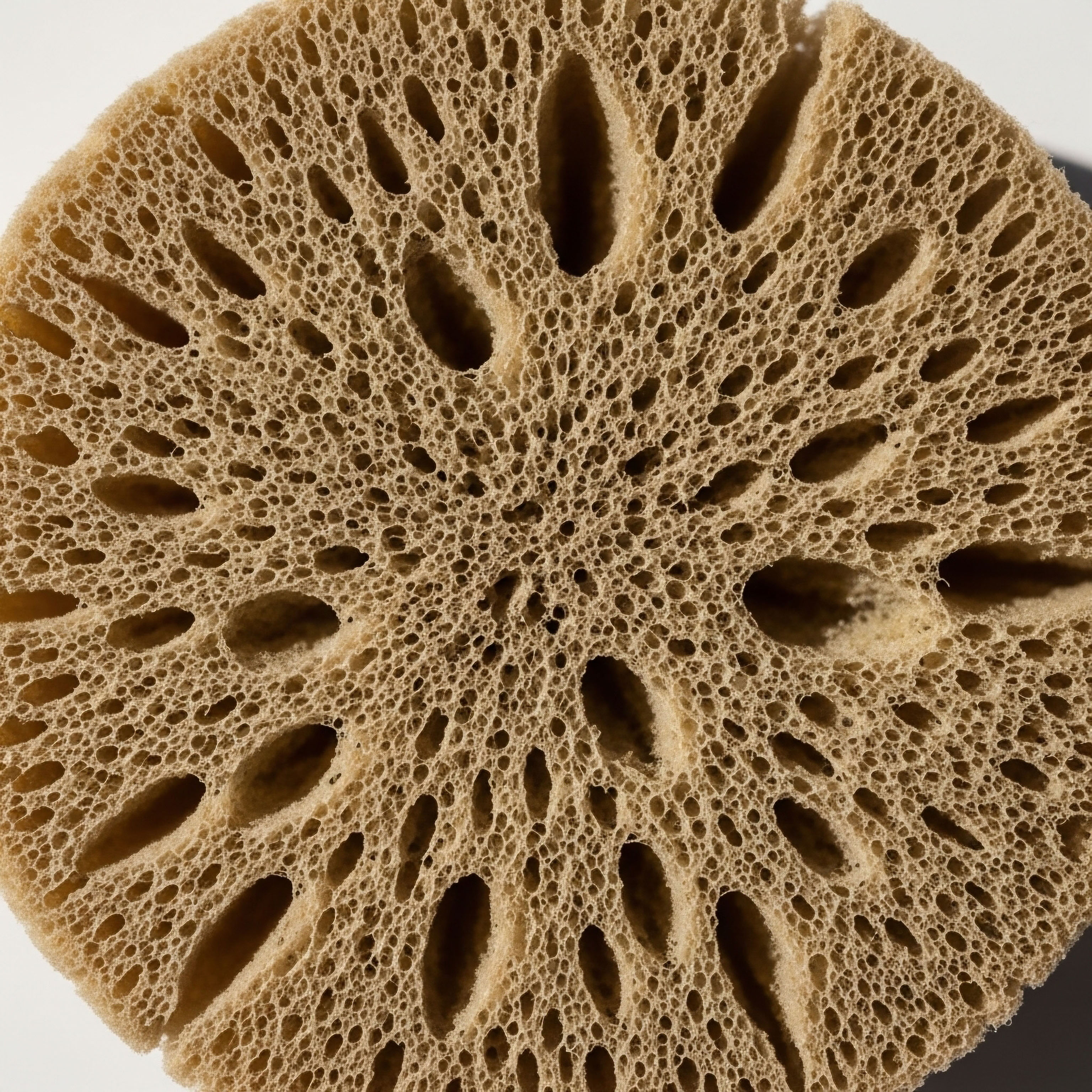

The conversation begins with understanding the different types of fats and their distinct roles. Think of them as different types of raw materials for a highly sophisticated factory. Some materials are perfect for constructing the delicate machinery of hormonal communication, while others can disrupt the entire production line.

The primary categories you will encounter are saturated fats, monounsaturated fats (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), which include both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Each one has a unique chemical structure that dictates how your body uses it.

The Architecture of Hormones

Steroid hormones, which include the sex hormones estrogen and testosterone as well as the stress hormone cortisol, are all derived from cholesterol. While your liver produces the majority of the cholesterol your body needs, the fats in your diet profoundly influence how this system functions.

Saturated fats, found in animal products and some tropical oils, can contribute to higher cholesterol levels. An excessive intake of these fats can place a burden on the liver. When the liver is occupied with processing a high load of saturated fat, its capacity to break down and clear out used hormones, particularly estrogen, can be diminished. This may lead to a recirculation of estrogen in the bloodstream, contributing to conditions of estrogen excess.

Your body’s ability to produce and regulate hormones is directly linked to the types and amounts of dietary fat you consume.

In contrast, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats, found in sources like avocados, olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish, play a more supportive role. They are integral to the structure of cell membranes, ensuring that your cells remain fluid and responsive to hormonal signals. A cell membrane that is flexible and healthy allows hormones to dock with their receptors effectively, much like a key fitting smoothly into a lock. This process is essential for proper hormonal communication and function throughout your body.

What Is the Consequence of Insufficient Fat Intake?

Just as an excess of certain fats can be problematic, an inadequate intake of dietary fat poses its own set of challenges to hormonal health. The body perceives very low-fat diets or severe caloric restriction as a state of famine. In response, it activates survival mechanisms, which often involves down-regulating non-essential processes like reproduction.

The production of sex hormones can decrease significantly, leading to menstrual irregularities in women or reduced testosterone in men. This is because the body lacks the necessary building blocks to create these hormones. Furthermore, the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins ∞ A, D, E, and K ∞ is dependent on dietary fat. These vitamins are themselves crucial for endocrine function, so a deficiency can create a cascade of hormonal disruptions.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of fats as building blocks, we can examine how specific dietary fat choices directly modulate key hormonal pathways. The type of fat you consume sends distinct signals that can either promote balance or create disruption within your endocrine system. This is particularly evident in how fats influence reproductive hormones and the intricate systems that regulate your metabolism, such as insulin and leptin signaling.

Your dietary choices have a measurable impact on the concentration of sex hormones. For instance, studies in regularly menstruating women have shown that a higher intake of total fat, especially from polyunsaturated sources, is associated with small increases in total and free testosterone concentrations.

While testosterone is often associated with male health, it is a vital hormone for women, contributing to libido, bone density, and muscle mass. Moreover, specific PUFAs, like docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), have been linked to increased progesterone levels and a reduced risk of anovulation (a cycle where no egg is released). This suggests that the quality of dietary fat can directly support the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and overall fertility.

The Fat and Insulin Connection

The relationship between dietary fat and insulin sensitivity is a critical aspect of long-term hormonal health. Insulin’s primary role is to shuttle glucose from the bloodstream into cells for energy. When this system works efficiently, blood sugar is well-regulated. Certain dietary fats, however, can interfere with this process.

Diets high in saturated and trans fats have been shown to increase insulin resistance. This means that your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals, forcing the pancreas to produce more of the hormone to get the job done. Chronic high levels of insulin can contribute to a host of metabolic issues and are a key feature of conditions like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

The composition of fats in your diet directly influences your cells’ sensitivity to key metabolic hormones like insulin and leptin.

Conversely, diets rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats tend to improve insulin sensitivity. These fats help maintain the fluidity of cell membranes, which allows insulin receptors to function optimally. An anti-inflammatory diet, rich in plant-based foods and healthy fats, can significantly improve how your body responds to insulin, thereby supporting metabolic balance and reducing the downstream hormonal consequences of insulin resistance.

Leptin Signaling and Appetite Regulation

Leptin is another hormone profoundly affected by your dietary fat choices. Produced by your fat cells, leptin’s job is to signal to your brain that you have sufficient energy stores, which in turn suppresses appetite. This is a crucial feedback loop for maintaining a stable body weight.

Chronic overconsumption of high-fat foods, particularly those high in saturated fats, can lead to a condition known as leptin resistance. In this state, your brain no longer properly “hears” leptin’s signal of satiety. This happens because high levels of saturated fatty acids can interfere with leptin’s ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and can disrupt its signaling pathway at the cellular level.

The result is a persistent feeling of hunger, even when the body has more than enough energy stored, creating a difficult cycle of overeating and weight gain.

| Fat Type | Primary Sources | Effect on Reproductive Hormones | Effect on Insulin Sensitivity | Effect on Leptin Signaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fat | Red meat, butter, coconut oil | Excess may impair liver clearance of estrogen. | Can increase insulin resistance. | Contributes to leptin resistance. |

| Monounsaturated Fat (MUFA) | Olive oil, avocados, nuts | Supports overall endocrine function. | Improves insulin sensitivity. | Supports healthy leptin signaling. |

| Omega-3 PUFA | Fatty fish, flaxseeds, walnuts | May reduce androgens in PCOS; supports progesterone. | Improves insulin sensitivity. | Decreases leptin levels and improves sensitivity. |

| Omega-6 PUFA | Vegetable oils (soy, corn) | High ratio to omega-3 linked to higher androgens in PCOS. | Variable; depends on balance with omega-3. | Excess can promote inflammation, affecting signaling. |

Improving leptin sensitivity is possible through dietary modification. Shifting the balance of fats in your diet away from saturated fats and towards omega-3 polyunsaturated fats can help restore the brain’s ability to recognize leptin’s signals. Anti-inflammatory diets rich in these healthy fats have been shown to decrease overall leptin levels and improve the body’s sensitivity to the hormone, aiding in appetite regulation and metabolic health.

Academic

A deeper, academic exploration of dietary fat’s long-term influence on hormonal health requires a systems-biology perspective. We must examine the molecular mechanisms through which fatty acids modulate the complex interplay between metabolic and reproductive endocrine axes. The chronic consumption of a very high-fat diet (VHFD) provides a compelling model for understanding this cascade of dysfunction.

Long-term studies, such as those conducted in animal models, reveal a sequence of events that begins with cellular changes and culminates in systemic endocrine disruption, particularly affecting the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

In a study observing mice on a VHFD for over 25 weeks, the initial effects were metabolic. The animals developed significant weight gain, hyperinsulinemia (chronically high insulin), and hyperleptinemia (chronically high leptin). This state of energy excess and metabolic dysregulation serves as the foundation for subsequent reproductive decline.

The adipose tissue, expanded by the high-fat diet, becomes a more significant endocrine organ itself, increasing its production of the enzyme aromatase. This enzyme converts testosterone to estradiol, leading to elevated estrogen levels in the blood. This biochemical shift is compounded by the fact that obesity can decrease the liver’s ability to inactivate estrogen, further increasing its bioavailability.

How Does the HPG Axis Become Disrupted?

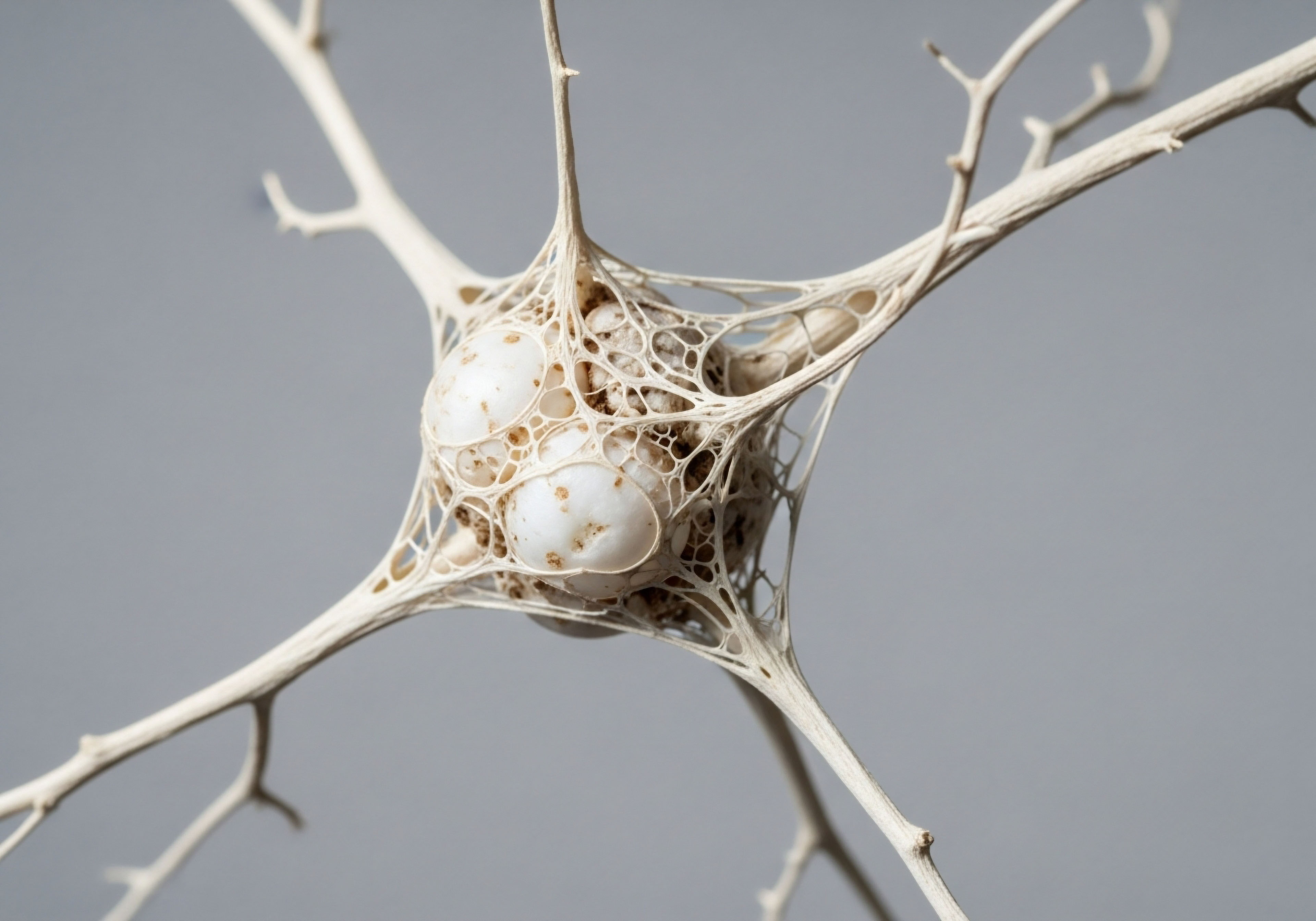

The hormonal chaos originating from the metabolic system sends disruptive signals “upstream” to the central control centers of the reproductive system. The HPG axis is a finely tuned feedback loop ∞ the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which signals the pituitary to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), which in turn act on the gonads to produce sex hormones.

Chronically elevated levels of leptin and insulin, hallmarks of a long-term high-fat diet, interfere with this delicate signaling cascade.

Long-term consumption of a high-fat diet initiates a cascade of metabolic and cellular changes that ultimately disrupt the central regulation of the reproductive system.

Leptin, in particular, plays a dual role. While it is necessary for the pulsatile release of GnRH that drives normal reproductive cycles, the state of hyperleptinemia induces leptin resistance within the central nervous system. This may be due to impaired transport of leptin across the blood-brain barrier or a downregulation of leptin receptors in the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus, effectively “blind” to the body’s true energy status, receives faulty signals. This leads to a dampening of the GnRH pulses, which disrupts the entire downstream signaling pathway. The ultimate consequence observed in the animal models was a complete shutdown of reproductive cyclicity, with females exhibiting persistent diestrus (a prolonged inactive phase) and anovulation.

- Hyperinsulinemia ∞ Chronically elevated insulin, a result of insulin resistance induced by the high-fat diet, directly impacts ovarian function and can contribute to excess androgen production.

- Hyperleptinemia ∞ Excess leptin from enlarged fat cells leads to central leptin resistance, disrupting the hypothalamic release of GnRH, the master controller of the reproductive axis.

- Aromatase Activity ∞ Increased adipose tissue boosts the activity of aromatase, an enzyme that converts androgens to estrogens, altering the systemic hormonal balance.

Cellular Stress and Endocrine Dysfunction

At a more granular level, the intake of excess dietary fat, particularly saturated fat, induces cellular stress that contributes to hormonal dysfunction. The over-nutrition leads to an increase in mitochondrial-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS). This state of oxidative stress can directly impair the sensitivity of cellular receptors, including the insulin receptor.

This creates a self-perpetuating cycle ∞ high-fat intake causes ROS, which impairs insulin sensitivity, which leads to higher insulin levels, which further promotes fat storage and inflammation. This inflammatory environment itself disrupts endocrine signaling. The chronic, low-grade inflammation associated with obesity and high-fat diets is a key mechanism through which dietary choices translate into systemic hormonal imbalance.

| Parameter | Observation in High-Fat Diet Group | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight | Significant increase | Higher caloric density of the diet and metabolic dysregulation. |

| Leptin Levels | Hyperleptinemia (chronically high) | Increased adipose tissue mass and secretion from enlarged adipocytes. |

| Insulin Levels | Hyperinsulinemia (chronically high) | Insulin resistance; pancreatic beta-cell hypertrophy to compensate. |

| Estradiol Levels | Significant increase | Increased aromatase activity in adipose tissue; reduced hepatic clearance. |

| Estrous Cycle | Complete acyclicity; prolonged diestrus | Negative feedback from metabolic hormones (leptin, insulin) on the HPG axis. |

References

- Mumford, S. L. et al. “Dietary fat intake and reproductive hormone concentrations and ovulation in regularly menstruating women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 103, no. 3, 2016, pp. 868-77.

- Hao, Lingling, et al. “Long-Term High Fat Diet Has a Profound Effect on Body Weight, Hormone Levels, and Estrous Cycle in Mice.” Medical Science Monitor, vol. 22, 2016, pp. 1633-41.

- Hales, C. N. and D. J. Barker. “The thrifty phenotype hypothesis.” British Medical Bulletin, vol. 60, 2001, pp. 5-20.

- Voinea, Talida. “Dietary fat consumption for women.” Talida Voinea, 18 Sept. 2020.

- The Institute for Functional Medicine. “Nutrition and Impacts on Hormone Signaling.” IFM, 22 Apr. 2025.

- Santoro, Nanette, et al. “Role of Estrogens and Estrogen-Like Compounds in Female Puberty.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 29, no. 6, 2015, pp. 843-54.

- Wang, Y. et al. “Hormonal and metabolic effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ results from a cross-sectional analysis and a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 93, no. 3, 2011, pp. 652-61.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here provides a map of the intricate connections between what you eat and how your internal world functions. It details the biochemical pathways and the systemic responses your body has to the fats you consume. This knowledge is the first, essential tool.

The next step in this process is one of personal translation. How do these complex systems manifest in your own lived experience? Understanding the science is the foundation, but applying it requires a shift in perspective ∞ from passively receiving information to actively observing your own body’s responses. Your personal health journey is a unique narrative, and this clinical understanding allows you to become its most informed author.