Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of being unwell that you cannot quite name. It could manifest as a deep fatigue that sleep does not resolve, a subtle but constant bloating after meals, or mood fluctuations that seem to have no external cause.

These feelings are valid and represent your body’s attempt to communicate a deeper systemic imbalance. The origin point for this widespread disruption is often found in the gastrointestinal tract, specifically within the sophisticated cellular lining known as the gut barrier.

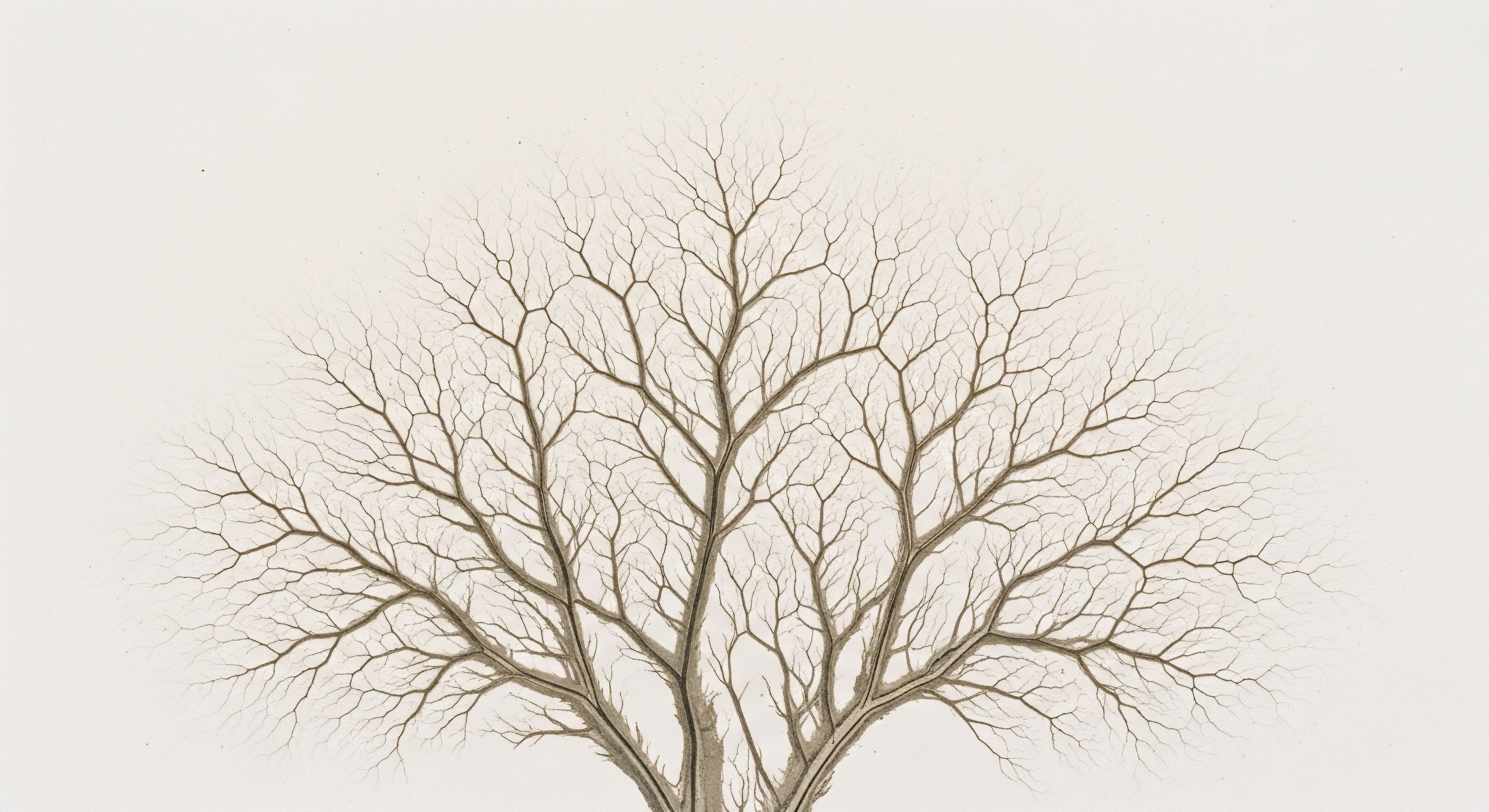

This barrier is the guardian of your internal environment, a complex and intelligent system designed to absorb life-sustaining nutrients while preventing harmful substances from entering your bloodstream. When the integrity of this barrier is weakened, a condition of increased intestinal permeability arises. This allows molecules that should remain within the digestive tract to pass into your circulation, initiating a cascade of biological responses that reverberate throughout your entire physiology.

The immediate consequence of a compromised gut barrier is the activation of the immune system. Your body’s defense mechanisms recognize these translocated particles, such as undigested food proteins and bacterial components, as foreign invaders. This triggers a low-grade, yet chronic, state of inflammation.

One of the most significant of these bacterial components is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a molecule found in the outer membrane of certain bacteria. When LPS enters the bloodstream, it acts as a powerful alarm signal, telling your body it is under threat. This persistent alarm state directly engages the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, your central stress response system.

The HPA axis governs the production of cortisol, a primary stress hormone. In short bursts, cortisol is essential for survival. A sustained, long-term elevation of cortisol driven by gut-derived inflammation, however, begins to dysregulate the delicate symphony of your endocrine system, setting the stage for profound hormonal health consequences.

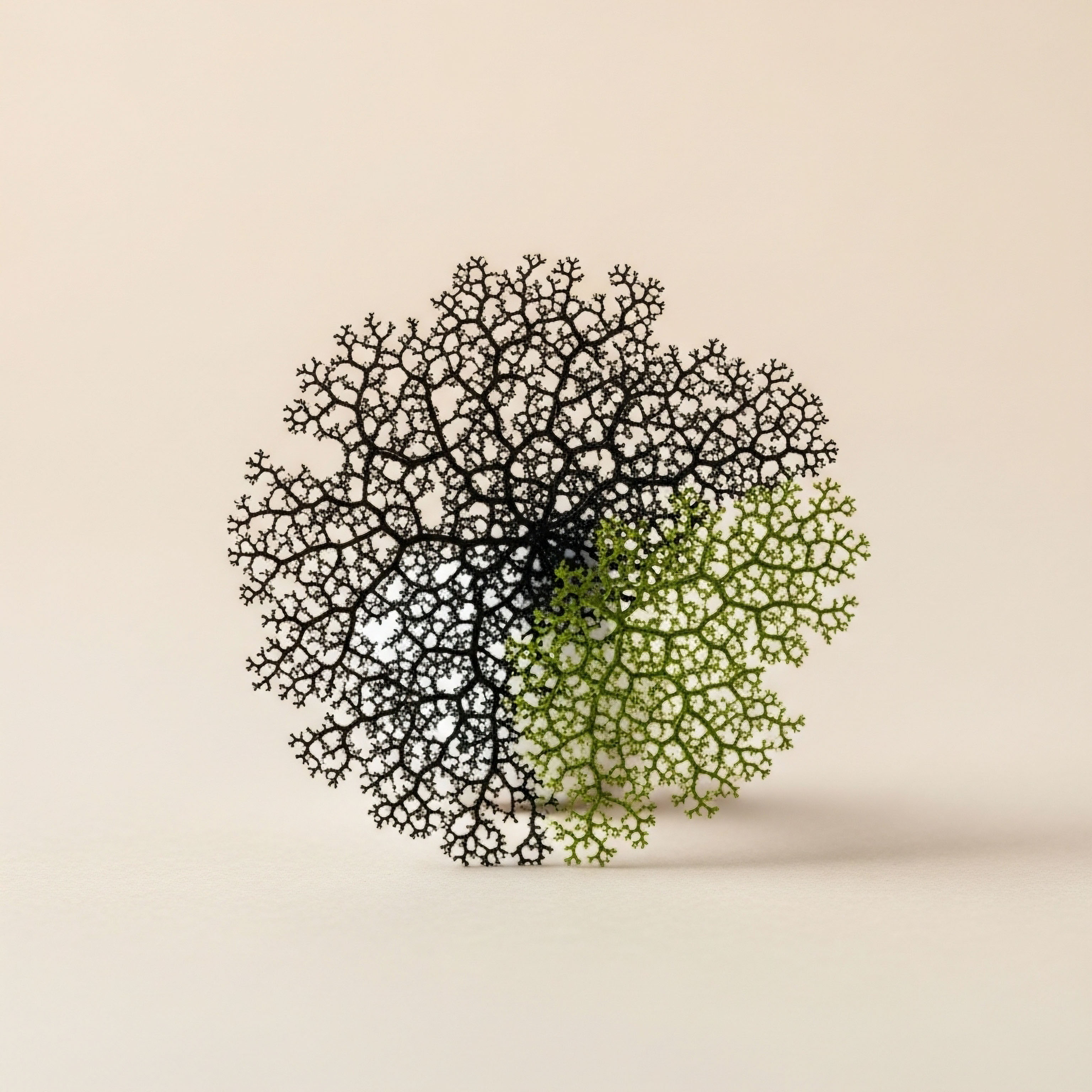

The Gut Barrier Your Body’s Primary Gatekeeper

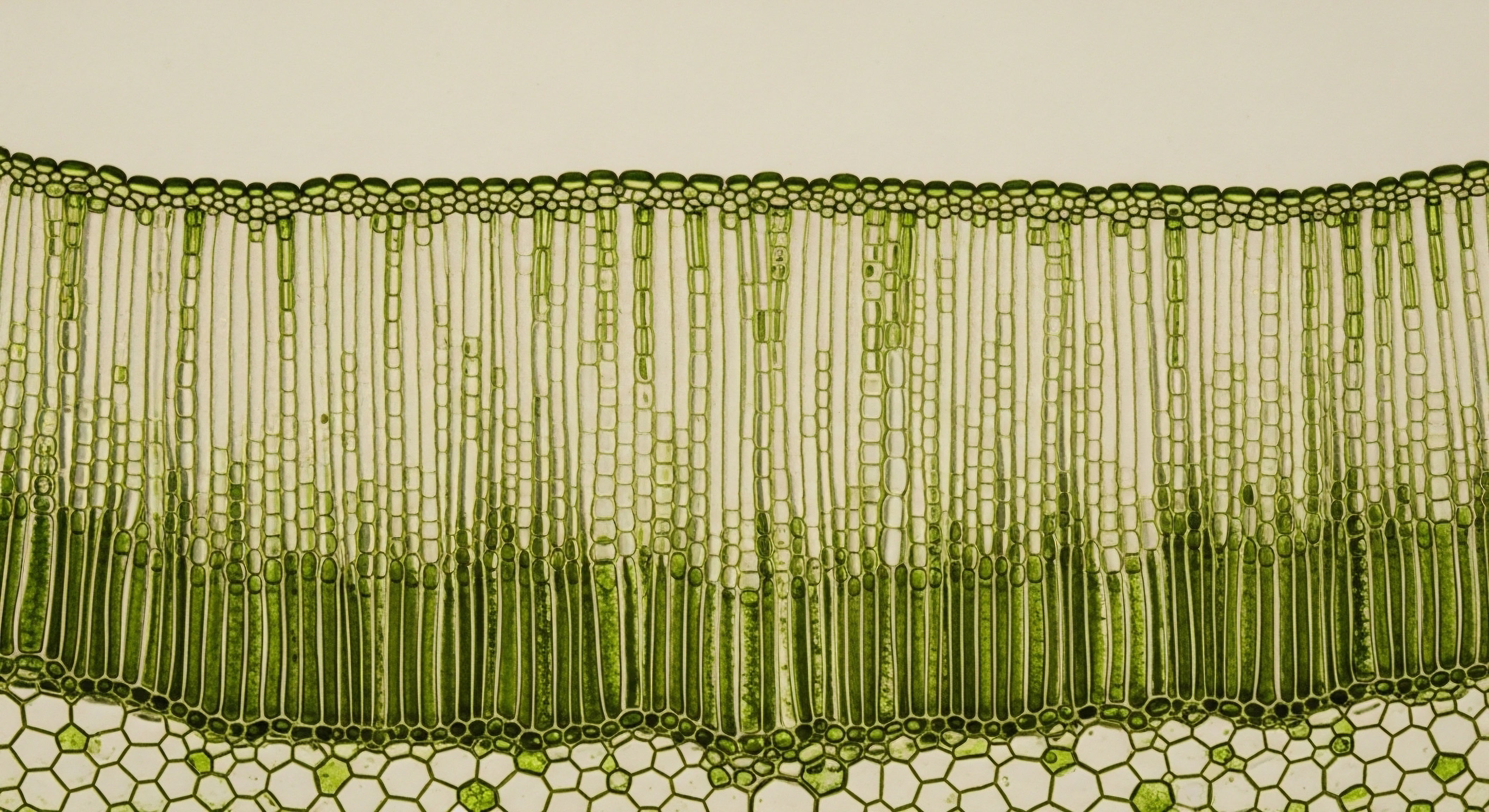

The intestinal lining is a remarkable structure. It is composed of a single layer of specialized epithelial cells linked together by protein complexes called tight junctions. These junctions act like meticulously controlled gates, opening just enough to allow water and essential nutrients to pass into the bloodstream while remaining sealed against larger, potentially harmful molecules.

The health of this barrier depends on a thriving and diverse community of microorganisms, the gut microbiota. These beneficial microbes help maintain the integrity of the tight junctions, digest fibers, produce essential vitamins, and even educate your immune system.

A poor diet, chronic stress, certain medications, and infections can disrupt this microbial ecosystem, leading to a state of imbalance known as dysbiosis. This dysbiosis directly contributes to the degradation of the gut barrier, loosening the tight junctions and creating the permeability that allows for systemic infiltration.

A compromised gut barrier allows inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream, triggering a chronic, low-grade immune response that disrupts hormonal signaling.

Understanding the gut barrier’s function is the first step in comprehending its far-reaching influence. Think of it as the most critical border crossing in your body. In a state of health, the border is secure. The guards are vigilant, the gates are strong, and only authorized traffic passes through.

When the barrier is compromised, the border becomes porous. Unauthorized traffic flows freely, creating chaos and requiring a constant, draining state of high alert from your internal security forces. This state of high alert is systemic inflammation, and its long-term effects are felt most acutely within the sensitive and interconnected world of your hormones.

The fatigue, the mood shifts, the unexplained weight changes ∞ these are often the downstream symptoms of a problem that begins with a breach at this fundamental boundary.

How Does a Compromised Barrier Affect Cortisol Levels?

The connection between a permeable gut and cortisol dysregulation is direct and well-documented. The entry of LPS into the circulation is a primary driver of this process. Immune cells throughout the body, including in the adrenal glands themselves, possess receptors that recognize LPS.

The binding of LPS to these receptors initiates a powerful inflammatory cascade. This inflammatory signaling directly stimulates the adrenal glands to produce and release cortisol. This biological mechanism means that a compromised gut can independently drive cortisol production, separate from the psychological or emotional stressors we typically associate with the stress response. Your body is locked in a physiological stress loop, fueled by the persistent leakage from your gut.

Over time, this constant demand on the HPA axis can lead to a state of adrenal dysfunction. Initially, cortisol levels may be chronically elevated, contributing to anxiety, insomnia, and the accumulation of visceral fat. Eventually, the system may become exhausted, leading to a blunted cortisol response where the body can no longer mount an adequate defense against stressors.

This can manifest as profound fatigue, low blood pressure, and a reduced capacity to handle daily life. This entire spectrum of HPA axis dysregulation, from chronic elevation to eventual burnout, can be traced back to the persistent inflammatory signals originating from a compromised gut barrier.

Addressing the source of the inflammation, the permeable gut itself, is therefore a foundational step in restoring the body’s natural stress resilience and hormonal equilibrium. This is the biological reality behind why you might feel perpetually stressed and exhausted, even when your external life circumstances seem manageable. Your internal environment is in a state of alarm, and the command center for that alarm is the compromised integrity of your gut.

Intermediate

The chronic inflammatory state initiated by a compromised gut barrier does not confine its effects to the stress axis alone. Its disruptive influence extends to every corner of the endocrine system, creating a complex web of hormonal imbalances that can profoundly impact quality of life.

The constant presence of inflammatory messengers, particularly lipopolysaccharide (LPS), acts as a systemic modulator, altering the production, transport, and reception of key hormones like estrogen, thyroid hormones, and testosterone. This process is one of biological interference, where the signals of inflammation overwhelm or distort the precise chemical messages upon which your body relies for healthy function.

Understanding these specific pathways of disruption is essential for appreciating the full scope of how gut health governs hormonal well-being and for designing effective, targeted therapeutic protocols.

The Estrobolome and Estrogen Imbalance

Estrogen, a hormone vital for both female and male health, undergoes a complex lifecycle of production, use, and elimination. The gut microbiome plays a direct and active role in this process through a specific collection of bacterial genes known as the “estrobolome.” These genes code for enzymes, most notably beta-glucuronidase, that can metabolize estrogens.

After the liver processes and conjugates estrogens to deactivate them for excretion, they are sent to the gut via bile. A healthy gut microbiome with a balanced estrobolome allows for the proper elimination of these deactivated estrogens in the stool. This maintains a healthy hormonal equilibrium.

However, in a state of dysbiosis, often seen with a compromised gut barrier, certain bacterial populations can overproduce the enzyme beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme effectively deconjugates, or reactivates, the estrogen that was meant for excretion. This reactivated estrogen is then reabsorbed back into the bloodstream, contributing to an overall excess of estrogen relative to other hormones like progesterone.

This condition, often termed estrogen dominance, can manifest in a wide array of symptoms. In women, this may include severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS), heavy or painful menstrual cycles, uterine fibroids, and an increased risk for estrogen-sensitive cancers. In men, excess estrogen can contribute to fat gain, reduced libido, and gynecomastia. The gut’s role is so central that the health of the estrobolome is now considered a key modulator of lifetime estrogen exposure and associated health outcomes.

Dysbiosis in the gut can reactivate estrogen destined for excretion, leading to hormonal imbalances like estrogen dominance.

Table Comparing Estrogen Metabolism

The following table illustrates the difference in estrogen processing in a state of gut health versus a state of dysbiosis and barrier compromise.

| Process Step | Healthy Gut (Eubiosis) | Compromised Gut (Dysbiosis) |

|---|---|---|

| Liver Conjugation | Estrogen is conjugated (inactivated) in the liver for safe removal. | Estrogen is conjugated (inactivated) in the liver for safe removal. |

| Excretion to Gut | Conjugated estrogen is secreted into the gut via bile. | Conjugated estrogen is secreted into the gut via bile. |

| Estrobolome Activity | Balanced beta-glucuronidase activity. Most conjugated estrogen remains inactive. | High beta-glucuronidase activity from specific bacterial overgrowths. |

| Estrogen Fate | Inactive estrogen is primarily excreted from the body in stool. | A significant portion of estrogen is deconjugated (reactivated). |

| Systemic Effect | Hormonal balance is maintained. | Reactivated estrogen is reabsorbed into circulation, leading to potential estrogen excess. |

Thyroid Function and Nutrient Malabsorption

The thyroid gland, the master regulator of your metabolism, is exquisitely sensitive to the systemic environment. A compromised gut barrier impacts thyroid function through two primary mechanisms ∞ direct interference with hormone conversion and impaired absorption of essential micronutrients. The majority of hormone produced by the thyroid is thyroxine (T4), which is relatively inactive.

For the body to use it, T4 must be converted into the biologically active form, triiodothyronine (T3). Approximately 20% of this vital conversion occurs in the gastrointestinal tract, mediated by enzymes produced by healthy gut bacteria. Gut dysbiosis can disrupt this conversion process, leading to a situation where T4 levels might appear normal on a lab test, yet the individual experiences all the symptoms of hypothyroidism due to a deficiency in active T3.

Furthermore, the chronic inflammation associated with a permeable gut can damage the intestinal lining, impairing its ability to absorb the very nutrients required for thyroid health. These include:

- Iodine ∞ A fundamental building block of thyroid hormones.

- Selenium ∞ A critical cofactor for the deiodinase enzyme that converts T4 to T3. Deficiency directly slows metabolism.

- Zinc ∞ Also required for T4 to T3 conversion and helps the hypothalamus regulate thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

- Iron ∞ Necessary for the proper function of thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme essential for hormone production.

This nutrient malabsorption creates a vicious cycle. The thyroid lacks the raw materials to produce and convert its hormones effectively, and the resulting low metabolic state can further slow gut motility, worsening the underlying dysbiosis. This connection explains why many individuals with thyroid disorders also suffer from significant digestive complaints and why healing the gut is a non-negotiable component of any effective thyroid optimization protocol.

Testosterone Suppression via Systemic Inflammation

In men, a compromised gut barrier and the resulting systemic inflammation can be a significant contributor to low testosterone levels. The Leydig cells in the testes, which are responsible for producing the vast majority of testosterone, are directly suppressed by inflammatory cytokines and bacterial endotoxins like LPS.

When LPS enters the bloodstream, it triggers an immune response that generates these inflammatory signals. These signals travel to the testes and essentially tell the Leydig cells to slow down production. This is a protective mechanism in the short term, as the body diverts resources away from reproduction to fight a perceived infection.

When the source of LPS is a chronically permeable gut, this suppression becomes a long-term state, leading to clinically low testosterone and the associated symptoms of fatigue, depression, loss of muscle mass, and diminished libido.

This inflammatory suppression occurs at multiple levels of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Inflammation can blunt the signal from the pituitary gland (luteinizing hormone, or LH) that tells the testes to make testosterone. It also directly impairs the enzymatic machinery within the Leydig cells themselves.

Therefore, even if the pituitary is sending the signal, the testes are less able to respond. This creates a state of testicular resistance to hormonal stimulation. For this reason, simply administering testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) without addressing the underlying gut-derived inflammation may only be a partial solution.

While TRT can restore serum hormone levels and alleviate symptoms, a comprehensive protocol would also focus on healing the gut barrier to reduce the inflammatory load, thereby improving the body’s own natural ability to produce and regulate testosterone.

Academic

A systems-biology perspective reveals the long-term consequences of compromised gut barrier function as a state of profound and persistent endocrine network disruption. The central mechanism is the chronic translocation of microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), principally lipopolysaccharide (LPS), from the gut lumen into systemic circulation.

This “metabolic endotoxemia” acts as a continuous, low-grade inflammatory stimulus that directly interfaces with the molecular machinery of the endocrine system. The primary point of interaction is through the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway.

TLR4 is expressed on a wide variety of cell types, including immune cells, adipocytes, and, critically, on the cells of the key endocrine glands themselves, including the adrenal cortex, the pancreatic islets, the thyroid, and the gonads. The chronic activation of TLR4 by circulating LPS initiates intracellular signaling cascades that alter gene expression, enzymatic activity, and cellular responsiveness, fundamentally recalibrating the body’s entire hormonal milieu.

LPS-Mediated Dysregulation of Steroidogenic Pathways

The impact of metabolic endotoxemia on hormonal health is deeply rooted in its ability to interfere with steroidogenesis, the multi-step biochemical process of converting cholesterol into steroid hormones. This process is highly regulated by a series of enzymes within the cytochrome P450 superfamily.

Research demonstrates that the inflammatory cytokines produced in response to TLR4 activation, such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), directly suppress the expression of key steroidogenic enzymes. For instance, in testicular Leydig cells, these cytokines downregulate the expression of Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory (StAR) protein, which is the rate-limiting step in moving cholesterol into the mitochondria where hormone synthesis begins.

They also suppress the activity of enzymes like P450scc (cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme) and 3β-HSD (3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase). This results in a direct, inflammation-mediated reduction in the synthesis of testosterone and its precursors.

A similar disruptive process occurs in the adrenal glands. While acute LPS exposure potently stimulates cortisol production, chronic exposure leads to a more complex dysregulation. The persistent inflammatory signaling can create a state of adrenal “hyper-reactivity” followed by eventual cellular exhaustion or resistance.

This is characterized by alterations in the expression of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes, leading to skewed hormonal output. For example, the body might begin to favor the production of cortisol at the expense of other vital hormones like DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone), a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “cortisol steal” or “pregnenolone steal.” This shunting of precursor hormones down the cortisol pathway deprives the body of the building blocks for sex hormones, contributing further to the global endocrine imbalance initiated by the compromised gut barrier.

Chronic activation of the TLR4 pathway by gut-derived lipopolysaccharide directly suppresses the enzymatic machinery responsible for producing steroid hormones.

What Is the Role of Hormonal Receptor Sensitivity?

The disruptive influence of chronic inflammation extends beyond hormone production to the level of hormone reception. For a hormone to exert its biological effect, it must bind to its specific receptor on a target cell. The persistent inflammatory state driven by metabolic endotoxemia can downregulate the expression and sensitivity of these receptors.

This creates a state of hormone resistance, where even if serum hormone levels are adequate, the body’s cells are less able to “hear” the hormonal message. This is a well-established mechanism in the context of insulin resistance, where chronic inflammation impairs the insulin receptor’s ability to signal for glucose uptake. An analogous process occurs with other hormone systems.

For example, inflammatory cytokines can decrease the sensitivity of androgen receptors, making the body less responsive to testosterone. Similarly, they can interfere with thyroid hormone receptors, contributing to the symptoms of hypothyroidism even in the presence of normal T3 levels.

This receptor-level desensitization is a critical and often overlooked aspect of the long-term effects of a compromised gut barrier. It explains why simply replacing a deficient hormone may not fully resolve all symptoms. A comprehensive clinical approach must also aim to quench the underlying inflammation to restore cellular sensitivity to hormonal signaling, allowing the body to properly utilize the hormones it has.

This highlights the necessity of therapeutic strategies that target the gut barrier and reduce the systemic inflammatory load as a prerequisite for effective hormonal optimization.

Table Summarizing LPS Impact on Endocrine Axes

The following table provides a synthesized overview of the academic understanding of how chronic, low-grade endotoxemia impacts the primary endocrine regulatory systems.

| Endocrine Axis | Key Glands Involved | Mechanism of LPS/Inflammatory Disruption | Resulting Hormonal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Adrenals | Direct stimulation of adrenal TLR4; cytokine-mediated activation of the axis at all levels. | Initial hypercortisolism, followed by potential for HPA axis burnout and hypocortisolism; altered cortisol/DHEA ratio. |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Gonads (Testes/Ovaries) | Suppression of GnRH release from the hypothalamus; blunting of pituitary LH signal; direct cytokine-mediated suppression of steroidogenic enzymes (e.g. StAR, P450scc) in gonads. | Reduced testosterone in men; dysregulated estrogen/progesterone balance in women; impaired fertility. |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Thyroid | Inhibition of TSH release; decreased peripheral conversion of T4 to active T3 due to suppression of deiodinase enzymes; impaired receptor sensitivity. | Functional hypothyroidism (normal TSH/T4 with low T3); symptoms of low metabolism. |

| Estrogen Metabolism (Estrobolome) | Liver, Gut Microbiome | Gut dysbiosis leads to overproduction of beta-glucuronidase by specific bacteria. | Increased deconjugation and reabsorption of estrogens from the gut, contributing to estrogen dominance. |

How Does This Connect to Long-Term Wellness Protocols?

This systems-level understanding provides the clinical rationale for integrating gut health protocols as a foundational element of any advanced wellness or hormonal optimization strategy. The administration of Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in men, for instance, is more effective in a low-inflammation environment where androgen receptors are sensitive.

For women undergoing hormonal balancing for perimenopausal symptoms, addressing the estrobolome to ensure proper estrogen clearance is a critical adjunct to therapy. Peptide therapies designed to support growth hormone release or tissue repair, such as Sermorelin or BPC-157, also function more effectively when the body is not burdened by a constant inflammatory state originating from the gut.

The ultimate goal of these protocols is to restore the body’s innate regulatory intelligence. This restoration is biologically impeded by a compromised gut barrier. Therefore, healing the gut through targeted dietary interventions, prebiotic and probiotic support, and reducing the sources of intestinal inflammation is a mandatory first step in re-establishing the endocrine network’s integrity and enabling the success of subsequent personalized health interventions.

References

- Ghanim, H. et al. “Endotoxemia and inflammation in obesity and a study of the effects of weight loss.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 94, no. 1, 2009, pp. 54-59.

- Kwa, M. Plottel, C. S. Blaser, M. J. & Adams, S. (2016). The Estrobolome ∞ A Novel Determinant of Estrogen-Related Diseases. mBio, 7(4), e00994-16.

- Tremellen, K. & Pearce, K. (2012). Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA) ∞ a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Medical Hypotheses, 79(1), 104-112.

- Knezevic, J. Starchl, C. Tmava Berisha, A. & Amrein, K. (2020). Thyroid-Gut-Axis ∞ How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function?. Nutrients, 12(6), 1769.

- Dandona, P. et al. “Testosterone and inflammation.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 11, 2007, pp. 4496-4502.

- Cani, P. D. et al. “Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance.” Diabetes, vol. 56, no. 7, 2007, pp. 1761-1772.

- Plaza-Díaz, J. et al. “Evidence of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics in Intestinal Chronic Diseases.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 6, 2017, p. 555.

- Moretti, C. et al. “Testosterone and libido in male and female.” Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, vol. 13, no. 3, 2006, pp. 249-253.

- Sarkar, A. et al. “Gut-Brain Axis and Flora-Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, vol. 10, no. 7, 2016, pp. ZE10-ZE14.

- Caruso, R. et al. “The gut-brain axis ∞ interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems.” Annals of Gastroenterology, vol. 31, no. 2, 2018, pp. 133-142.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a biological framework for understanding the connection between your internal state and your lived experience. The science of the gut-hormone connection offers a powerful validation for the symptoms you may be feeling, grounding them in tangible physiological processes.

This knowledge shifts the perspective from one of passive suffering to one of active participation in your own health. It repositions the gut barrier not as a source of problems, but as a potent and accessible target for intervention and healing. Your body possesses a profound capacity for self-regulation and repair.

The journey toward reclaiming vitality begins with understanding and supporting the foundational systems that govern your well-being. Consider how these interconnected systems manifest in your own life. Reflect on the signals your body is sending you, now armed with a deeper appreciation for the language it speaks. This understanding is the first and most meaningful step toward building a personalized protocol that restores balance from the inside out, allowing you to reclaim function and feel whole again.

Glossary

gut barrier

intestinal permeability

compromised gut barrier

hormonal health

cortisol

systemic inflammation

hpa axis

hpa axis dysregulation

gut microbiome

estrobolome

estrogen dominance

the estrobolome

leydig cells