Fundamentals

The persistent feeling of exhaustion, the mental fog that clouds your thinking, and the frustrating sense that your body is holding onto weight despite your best efforts are tangible experiences. These are not isolated symptoms of a busy life.

They are often the direct result of a deep, biological conversation happening within your body, a conversation where the urgent demands of chronic stress begin to overpower the systems that regulate your long-term vitality. Understanding this internal dialogue is the first step toward reclaiming your energy and metabolic health.

At the center of this dynamic are two powerful command centers ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, your stress response system, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) axis, which governs your metabolism.

Think of your body as a sophisticated organization with a limited budget of energy and resources. The HPT axis is the department of long-term investments and infrastructure. It meticulously manages your metabolic rate, body temperature, and the energy allocated to every cell for growth and repair.

It does this through a precise cascade of hormonal signals. The hypothalamus releases Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH), which signals the pituitary gland to produce Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH). TSH then travels to the thyroid gland, instructing it to produce its primary hormones, mainly Thyroxine (T4) and a smaller amount of Triiodothyronine (T3).

T4 is a storage hormone, a stable precursor that must be converted into the biologically active T3 in the peripheral tissues, like the liver and muscles, to actually turn up the metabolic dial in your cells. This entire system is designed for steady, sustainable energy management.

Chronic stress systematically disrupts the body’s metabolic regulation by forcing a shift from long-term energy management to immediate survival responses.

The Stress Response System Takeover

The HPA axis, conversely, is the emergency response department. When you encounter a stressor ∞ be it psychological, emotional, or physical ∞ the HPA axis springs into action. The hypothalamus releases a signal that tells the pituitary to activate the adrenal glands, which then flood the body with cortisol.

In short bursts, cortisol is incredibly useful. It sharpens your focus, mobilizes energy stores, and reduces inflammation, preparing you to handle an immediate threat. The system is designed for acute, temporary challenges. The biological wiring of the human body, however, struggles to differentiate between a physical threat and the relentless pressure of modern life. Financial worries, relationship stress, and chronic overwork can keep the HPA axis in a state of constant activation.

When this state becomes chronic, the body enters a mode of perpetual crisis management. From a resource allocation perspective, it decides that long-term projects like robust metabolism, reproduction, and cellular repair are luxuries it cannot afford. The priority shifts entirely to immediate survival.

This is where the direct and often damaging communication with the thyroid system begins. High levels of cortisol send a powerful signal throughout the body to conserve energy. This message is interpreted by the HPT axis as a command to slow down its operations, leading to profound changes in the availability of active thyroid hormone.

How Stress Silences the Metabolic Engine

The long-term effects of this stress-induced suppression are not always immediately obvious on a standard thyroid panel, which often just looks at TSH and maybe Total T4. The problem lies deeper, in the conversion process that activates thyroid hormone.

Chronic cortisol exposure directly interferes with the critical step of converting inactive T4 into active T3 in the tissues where it is most needed. This creates a situation where your pituitary and thyroid gland might appear to be functioning correctly, yet your body’s cells are starving for the active T3 they need to function optimally. You feel the effects as fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and cognitive sluggishness because your cellular metabolism is being deliberately turned down.

Furthermore, the body has another mechanism to put the brakes on metabolism. Under stress, it not only reduces the conversion of T4 to active T3 but also shunts more T4 down a different pathway, creating a molecule called reverse T3 (rT3).

Reverse T3 is an inactive form of the hormone that fits into the same cellular receptors as active T3. By occupying these receptors, rT3 acts as a blocker, preventing the active T3 that is available from doing its job.

This dual effect ∞ reducing the production of active T3 while simultaneously increasing the presence of its inhibitor ∞ is a powerful way the body conserves energy during perceived emergencies. When the emergency never ends, you are left with a suppressed metabolic state that becomes your new normal.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the long-term impact of chronic stress on your thyroid health, we must move beyond a generalized understanding and examine the specific changes that appear on a comprehensive thyroid panel. The story is told not just by TSH, but by the intricate balance between free hormones and the efficiency of their conversion.

An intelligent reading of these markers reveals the precise mechanisms through which the body’s stress response systematically downgrades its metabolic capacity. This understanding is foundational for developing targeted wellness protocols, including hormonal optimization strategies for both men and women, which aim to restore systemic balance.

Deconstructing the Thyroid Panel under Stress

A standard thyroid screening might only measure TSH and perhaps Total T4, which can be misleading. A person suffering from the metabolic consequences of chronic stress can present with a TSH that is within the “normal” lab range. This occurs because the primary disruption is happening in the peripheral tissues, not necessarily at the level of the pituitary gland initially.

Persistently high cortisol levels from an overactive HPA axis directly suppress the pituitary’s output of TSH, but this effect can be subtle. The real story unfolds when we look further.

- Free T4 (Thyroxine) This is the unbound, bioavailable portion of the main hormone produced by the thyroid gland. In the early to intermediate stages of chronic stress, Free T4 levels may remain within the normal range. The gland is still producing the raw material.

- Free T3 (Triiodothyronine) This measures the unbound, active hormone that drives metabolism in the cells. This is a critical marker. Under chronic stress, Free T3 levels will often be low or in the low-normal part of the reference range. This reflects the impaired conversion of T4 to T3.

- Reverse T3 (rT3) This measures the inactive blocker hormone. High levels of cortisol directly promote the conversion of T4 into rT3. A high rT3 level is a hallmark of stress-induced thyroid dysfunction and cellular hypothyroidism.

- T3/rT3 Ratio This calculated ratio is perhaps one of the most insightful markers for assessing cellular thyroid function. A low ratio indicates that a disproportionate amount of T4 is being converted into the inactive rT3 instead of the active T3, a clear sign of metabolic adaptation to stress.

The clinical picture of stress-induced thyroid dysfunction is characterized by low active T3 and high reverse T3, even when TSH appears normal.

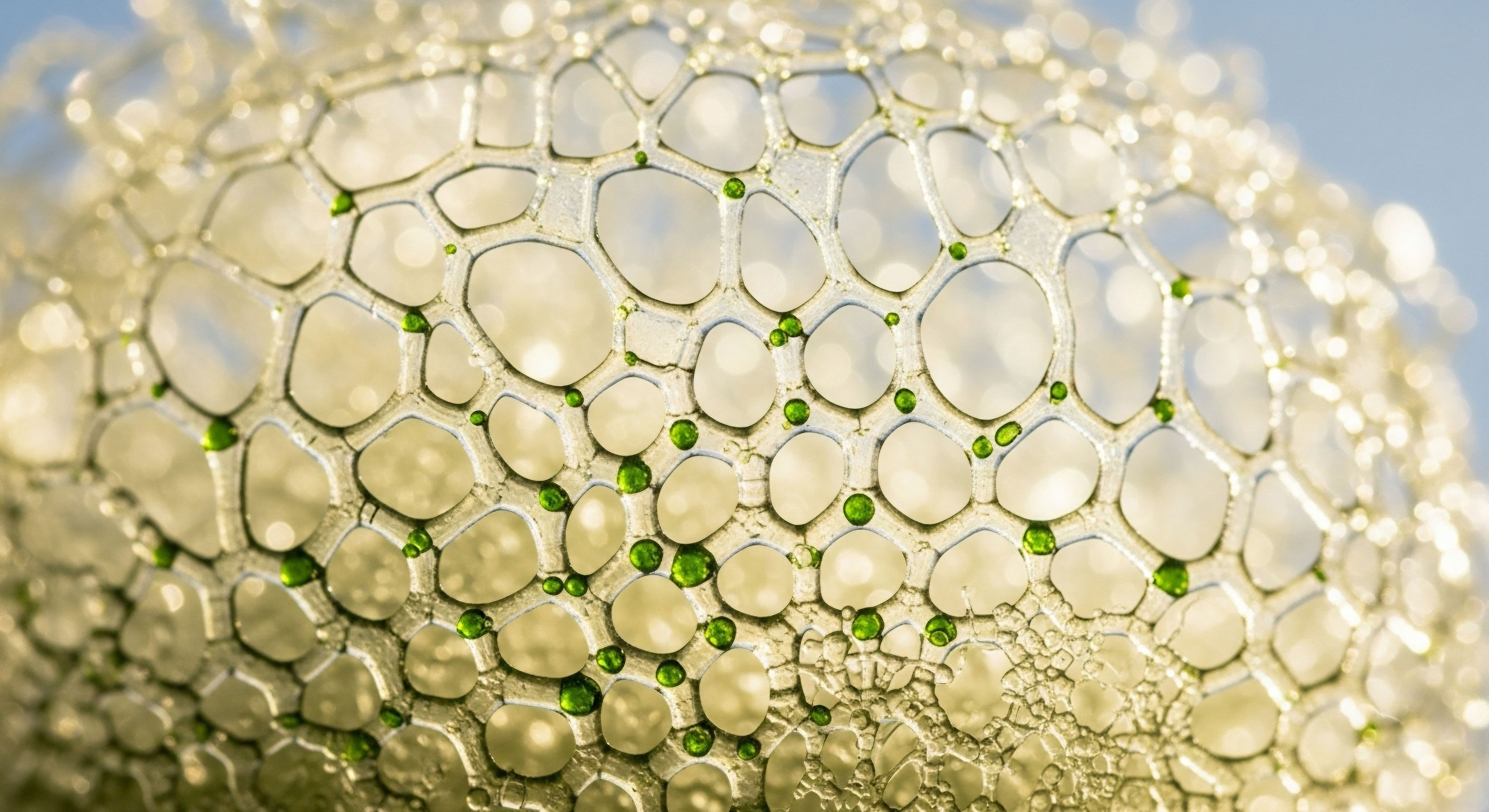

The Role of Deiodinase Enzymes

The conversion of thyroid hormones is regulated by a family of enzymes called deiodinases. Their activity is profoundly influenced by cortisol.

- Type 1 Deiodinase (D1) Found primarily in the liver and kidneys, D1 converts T4 to T3 in the bloodstream, contributing to circulating T3 levels. Chronic stress and high cortisol suppress D1 activity.

- Type 2 Deiodinase (D2) Found in the brain, pituitary, and other tissues, D2 converts T4 to T3 for local use within the cell. This allows the pituitary to sense thyroid hormone levels. Stress can increase D2 activity in the pituitary, which tricks the brain into thinking there is plenty of thyroid hormone, further suppressing TSH release even when the rest of the body is deficient.

- Type 3 Deiodinase (D3) This is the primary enzyme that inactivates thyroid hormones by converting T4 to rT3 and T3 to an inactive form. Cortisol strongly upregulates D3 activity throughout the body, effectively slamming the brakes on metabolism.

Connecting Thyroid Health to Systemic Wellness Protocols

Understanding this intricate hormonal interplay is vital because thyroid function does not exist in a vacuum. It is deeply connected to other endocrine systems, particularly the gonadal axis responsible for testosterone and estrogen production. Chronic stress, which suppresses the HPT axis, also suppresses the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The body, prioritizing survival, shuts down reproductive and anabolic functions. This can manifest as low testosterone in men and menstrual irregularities or menopausal symptom exacerbation in women.

Therefore, a comprehensive approach to wellness must address these interconnected systems. For a male patient experiencing fatigue, low libido, and difficulty building muscle, lab work might reveal low Free T3, high rT3, and low testosterone. A protocol may involve Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), perhaps using Testosterone Cypionate combined with Gonadorelin to maintain testicular function, to restore anabolic signaling.

This restoration of testosterone can improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic function, which supports better thyroid hormone activity. For a perimenopausal female patient with similar symptoms of fatigue and brain fog, a protocol might involve low-dose Testosterone Cypionate and bio-identical Progesterone. By supporting the entire endocrine system, these hormonal optimization protocols help counteract the global suppressive effects of chronic stress, creating a more favorable internal environment for healthy thyroid function.

| Marker | Healthy Euthyroid State | Chronic Stress-Induced State |

|---|---|---|

| TSH | Optimal (e.g. 0.5-2.0 mIU/L) | Normal to Low-Normal (e.g. 1.0-2.5 mIU/L) |

| Free T4 | Mid-to-High Normal Range | Normal to Low-Normal Range |

| Free T3 | Mid-to-High Normal Range | Low or Low-Normal Range |

| Reverse T3 | Low in Range | High in Range |

| Free T3 / rT3 Ratio | High | Low |

Academic

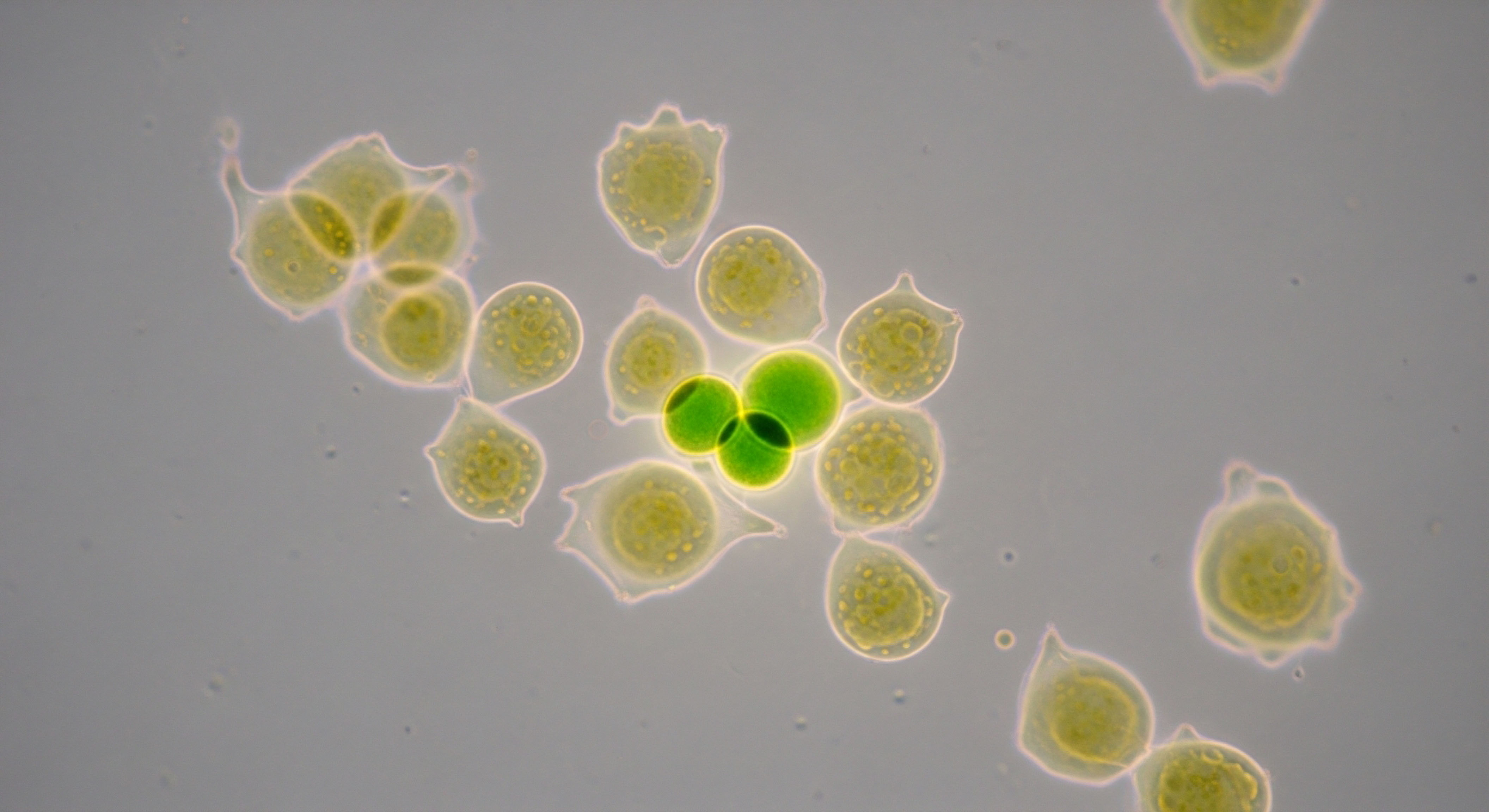

The constellation of thyroid marker abnormalities observed under chronic stress represents a physiological state that bears a striking resemblance to Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome (NTIS), also known as Euthyroid Sick Syndrome (ESS).

While NTIS is typically diagnosed in the context of acute, severe illness, trauma, or caloric restriction, a deep examination of the pathophysiology reveals that chronic psychosocial and physiological stress can induce a similar, albeit more prolonged and insidious, pattern of endocrine dysregulation. This dysregulation is a highly orchestrated, systemic adaptation designed to minimize energy expenditure during a period of perceived threat, mediated by inflammatory cytokines, glucocorticoids, and profound changes in deiodinase enzyme kinetics.

Pathophysiology of Stress-Induced NTIS

The central event in the development of stress-induced thyroid suppression is the sustained activation of the HPA axis and the resultant hypercortisolemia. Cortisol exerts its influence on the HPT axis at multiple levels. At the central level, cortisol, along with stress-induced inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, suppresses the release of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

This leads to a diminished pulsatility and amplitude of Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) secretion from the pituitary, effectively reducing the primary stimulus to the thyroid gland. This central suppression is a key feature of NTIS and explains why TSH levels are often paradoxically normal or low in individuals who are functionally hypothyroid at the cellular level.

The most significant alterations, however, occur in the peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormones. This process is governed by the three deiodinase enzymes, which are differentially regulated by cortisol and inflammatory signals.

| Enzyme | Primary Location | Function | Effect of Cortisol & Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 (D1) | Liver, Kidney, Thyroid | Converts T4 to T3 for systemic circulation. | Downregulated, decreasing serum T3. |

| Type 2 (D2) | Brain, Pituitary, Brown Adipose Tissue | Converts T4 to T3 for local intracellular use. | Downregulated in periphery; upregulated in pituitary, suppressing TSH. |

| Type 3 (D3) | Placenta, Fetal Tissues, Brain, Skin | Inactivates T4 to rT3 and T3 to T2. | Strongly upregulated, increasing rT3 and clearing active T3. |

This coordinated enzymatic shift results in the characteristic biochemical signature of NTIS ∞ low serum T3, high serum rT3, and a normal-to-low TSH. The elevated rT3 acts as a competitive antagonist at the thyroid hormone receptor (TR), further blocking the action of any remaining T3.

The body is effectively engineering a state of cellular hypothyroidism as a protective, energy-sparing adaptation. In the context of an acute illness, this is a transient and beneficial survival mechanism. When driven by chronic stress, it becomes a persistent state of maladaptation, underpinning symptoms of fatigue, metabolic slowdown, and cognitive decline.

The endocrine signature of chronic stress mirrors Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome, reflecting a systemic, adaptive downregulation of cellular metabolism.

Interplay with the Gonadal and Somatotropic Axes

The suppressive effects of chronic stress are not confined to the thyroid axis. The same mediators ∞ cortisol and inflammatory cytokines ∞ that induce an NTIS-like state also exert potent inhibitory effects on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) and Growth Hormone (GH)/Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) axes.

Normal thyroid function is permissive for proper gonadal activity. Thyroid hormones are required for normal Leydig cell function and testosterone synthesis in men and for follicular development and estrogen production in women. The low T3 state seen in chronic stress can therefore exacerbate the direct suppression of the HPG axis, contributing to hypogonadism in males and menstrual dysfunction in females.

What Are the Systemic Consequences for Hormone Protocols?

This interconnected web of endocrine suppression has significant implications for clinical practice. Attempting to correct low testosterone with TRT or menopausal symptoms with hormonal protocols without addressing the underlying stress-induced thyroid dysfunction may yield suboptimal results. The cellular machinery is still in a state of energy conservation.

A truly effective protocol must be systems-based. This could involve the use of growth hormone peptides like Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295 to counteract the suppression of the somatotropic axis, which can improve cellular energy and lean body mass. Concurrently, addressing the high rT3 state may be necessary.

This systems-biology approach acknowledges that the symptoms are downstream manifestations of a global survival response. The goal is to send a signal of safety and resource abundance to the central command centers in the hypothalamus, allowing the body to shift out of its chronic, low-power state and restore the function of the thyroid, gonadal, and growth hormone axes in concert.

References

- Chrousos, G. P. “Stress and disorders of the stress system.” Nature reviews Endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 7, 2009, pp. 374-81.

- Farhangi, M. A. et al. “The effect of stress on the correlation between thyroid hormones, cortisol and anthropometric measurements.” Acta bio-medica ∞ Atenei Parmensis, vol. 90, no. 4, 2019, pp. 493-499.

- Manipal Hospitals. “How Stress Affects Your Thyroid ∞ The Science Explained.” 2025.

- Boelen, A. et al. “Mechanisms behind the non-thyroidal illness syndrome ∞ an update.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 209, no. 2, 2011, pp. 139-46.

- Janssen, O. E. et al. “Stress & Thyroid Function ∞ From Bench to Bedside.” Thyroid International, 2019.

- Wajner, S. M. and A. L. Maia. “Clinical implications of altered thyroid status in male testicular function.” Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia, vol. 56, no. 1, 2012, pp. 53-62.

- Kelly, G.S. “Peripheral Thyroid Hormone Conversion and Its Impact on TSH and Metabolic Activity.” Journal of Restorative Medicine, vol. 3, no. 1, 2014, pp. 103-112.

- Fekete, C. and R. M. Lechan. “Central regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis.” Thyroid Function, Springer, 2014, pp. 1-30.

- Pop, V. J. et al. “The role of thyroid function in female and male infertility ∞ a narrative review.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 974969.

- Wagner, M. S. et al. “The role of thyroid hormone in testicular development and function.” Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 199, no. 3, 2008, pp. 351-65.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Compass

The data presented on your lab reports and the biological mechanisms described here are more than just clinical information. They are pages from your own body’s logbook, detailing its journey and the adaptations it has made to navigate the environment you inhabit.

The fatigue, the cognitive changes, the metabolic shifts ∞ these are signals from a system working diligently to protect you based on the inputs it receives. The question that follows this understanding is a personal one ∞ What inputs is your body consistently receiving?

Viewing stress as a physiological load rather than a purely mental or emotional state allows for a different kind of self-inventory. It prompts an evaluation of all the factors that demand an energy tribute from your system. This knowledge empowers you to move from a reactive position, managing symptoms as they arise, to a proactive one.

It becomes a process of recalibrating your internal compass, consciously sending signals of safety, recovery, and stability that allow your body’s sophisticated hormonal networks to shift from a state of survival to one of optimization. This is the foundation of a personalized path toward reclaiming your vitality, a path that begins with listening to the clear, biological story your body is telling.