Fundamentals

You may have arrived here holding a genuine concern, a question born from observing changes in your own body. Perhaps it’s the sight of more hair in the brush or a subtle thinning at the temples that has prompted you to seek answers and regain a sense of control.

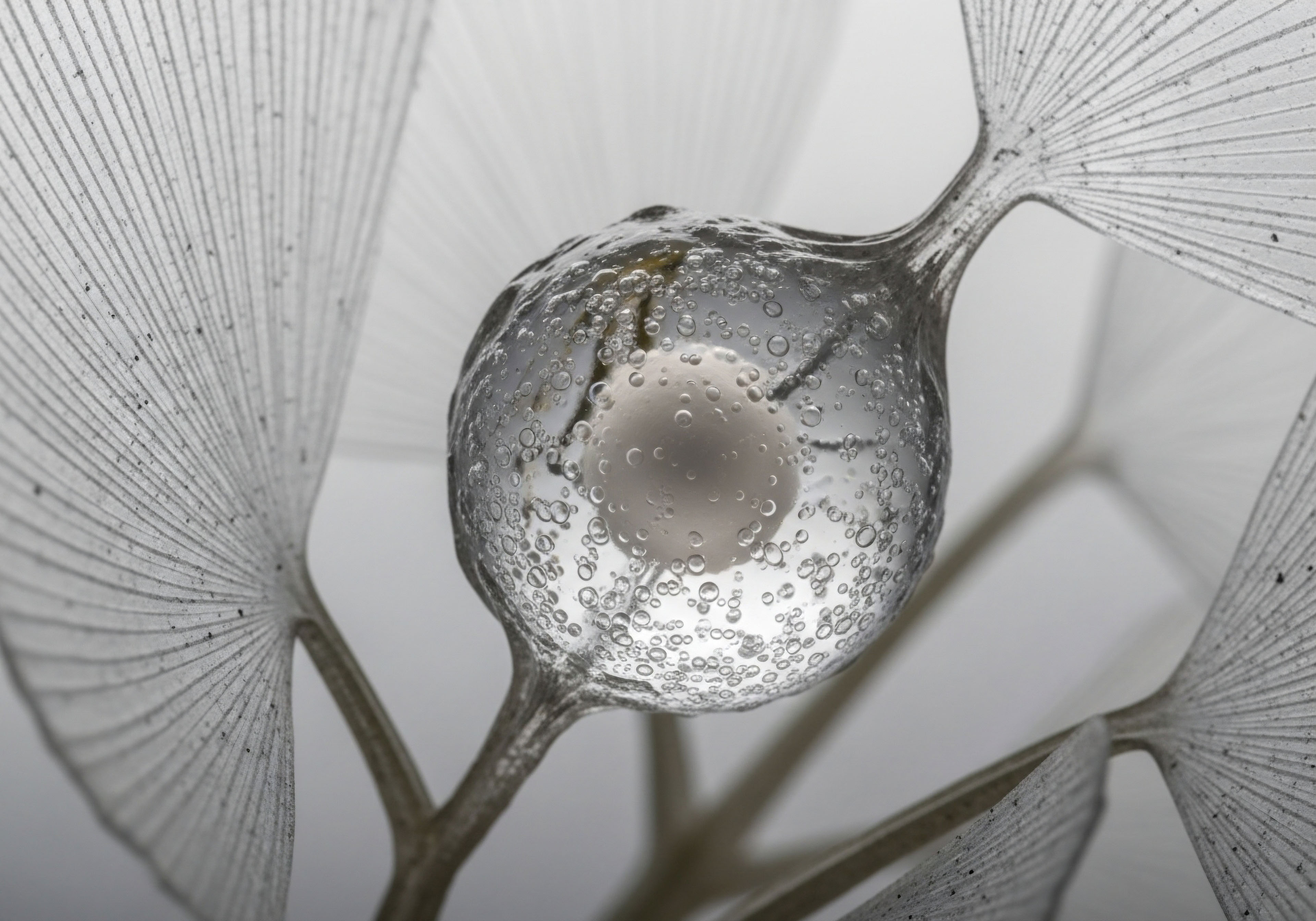

Your experience is valid, and it points toward a fundamental biological process occurring within your body’s intricate communication network. Understanding this network is the first step toward informed action. Your body operates as a finely tuned system of messages and responses, with hormones acting as the primary chemical messengers. The health and life cycle of your hair follicles are directly influenced by these hormonal signals, particularly by a class of hormones known as androgens.

Androgens, such as testosterone, are often associated with male characteristics, yet they are vital for the health of both men and women, influencing everything from bone density and muscle mass to mood and libido. Within this family of androgens, one specific molecule, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), plays a particularly potent role in hair.

DHT is synthesized from testosterone through the action of an enzyme called 5-alpha reductase (5-AR). In individuals with a genetic predisposition for androgenic alopecia (pattern hair loss), hair follicles on the scalp become highly sensitive to DHT. This sensitivity causes the follicles to miniaturize, shortening their growth phase and eventually leading to the fine, light-colored vellus hairs characteristic of thinning.

The journey to understanding hair health begins with recognizing the profound influence of hormonal messengers on the lifecycle of each hair follicle.

An anti-androgenic diet is a nutritional strategy designed to gently modulate these hormonal signals. This approach works through several distinct biological pathways. Some foods contain compounds that can partially inhibit the 5-alpha reductase enzyme, effectively turning down the conversion of testosterone to the more powerful DHT.

Other foods provide plant-derived compounds called phytoestrogens, which have a molecular structure similar to the body’s own estrogen. These phytoestrogens can interact with hormone receptors, sometimes competing with androgens and subtly altering the overall hormonal balance. A third mechanism involves modulating levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein that binds to hormones in the bloodstream.

By influencing SHBG, certain dietary choices can change the amount of free, biologically active androgens available to interact with tissues like your hair follicles.

Viewing this from a systems perspective, the hair on your head is an external indicator of a complex internal environment. The goal of a thoughtfully constructed anti-androgenic diet is to create subtle shifts in this environment. It involves providing your body with specific micronutrients and phytochemicals that support a more favorable hormonal equilibrium for hair preservation.

This is a process of recalibration, supplying the body with inputs that encourage a desired biological output. Your personal health journey is unique, and understanding these foundational principles empowers you to see your dietary choices as a meaningful form of communication with your own physiology.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational concepts of hormonal influence, we can examine the specific biochemical interactions that define an anti-androgenic diet. This requires a closer look at the active compounds within certain foods and the clinical evidence that illuminates their effects on human physiology.

The mechanisms are precise, involving enzymatic pathways and receptor-level interactions that, when influenced consistently over time, can produce measurable changes in your body’s endocrine landscape. Appreciating these details allows for a more targeted and effective nutritional strategy.

How Do Specific Foods Modulate Androgen Signals?

The modulation of androgenic activity through diet is a nuanced process. Different foods and their constituent compounds interact with the endocrine system through distinct, well-defined pathways. Understanding these pathways is key to assembling a diet that aligns with your wellness goals.

Inhibition of 5-Alpha Reductase

The 5-alpha reductase enzyme is a primary target for androgen modulation. While pharmaceutical inhibitors like finasteride and dutasteride block this enzyme with high potency, certain dietary components can exert a similar, albeit much milder, effect. Green tea, for instance, is rich in a catechin known as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG).

In vitro and animal studies have shown that EGCG can bind to the 5-AR enzyme, reducing its capacity to convert testosterone into DHT. Similarly, zinc, a mineral abundant in pumpkin seeds and legumes, acts as a 5-AR inhibitor. A deficiency in zinc has been correlated with increased 5-AR activity.

Therefore, ensuring adequate zinc intake is a foundational aspect of managing DHT levels through diet. These dietary interventions provide a gentle, systemic nudge to the enzyme’s activity, contributing to a lower overall DHT burden over the long term.

The Role of Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens, particularly the isoflavones found in soy and the lignans in flaxseed, represent another significant pathway of dietary androgen modulation. These plant-based compounds possess a molecular structure that allows them to bind to the body’s estrogen receptors.

Their effect is complex; they can exert a weak estrogenic effect or, in some cases, block the action of the body’s more potent endogenous estrogen. This interaction has a downstream effect on androgens. Phytoestrogens have been shown in some studies to increase the production of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG) in the liver.

SHBG is a protein that binds tightly to testosterone in the bloodstream, rendering it inactive. An increase in SHBG results in a decrease in free testosterone, the portion that is biologically active and available for conversion to DHT. The clinical data on phytoestrogens can be inconsistent, likely due to individual differences in gut microbiota, which are responsible for metabolizing these compounds into their most active forms. This variability underscores the personalized nature of dietary interventions.

Specific foods contain bioactive compounds that interact directly with hormonal pathways, offering a method of gentle, long-term endocrine modulation.

A Case Study Spearmint Tea

Spearmint tea provides a clear clinical example of a dietary intervention with measurable anti-androgenic effects. Several randomized controlled trials have investigated its use in women with hirsutism (excess hair growth), a condition driven by high androgen levels, often associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

In a 30-day trial, women who drank spearmint tea twice daily showed a significant reduction in free and total testosterone levels compared to a placebo group. While the objective scores for hair reduction did not reach statistical significance in this short timeframe, the participants’ self-reported assessments of their condition showed significant improvement.

This discrepancy is biologically logical. The hair growth cycle is long, and a reduction in androgen levels today will take several months to manifest as a visible change in hair thickness and growth. The research on spearmint confirms that a simple dietary addition can create a tangible shift in hormonal balance.

Systemic Considerations and Long-Term Outlook

When implementing an anti-androgenic diet, it is important to maintain a systems-wide perspective. Androgens do more than influence hair; they are integral to libido, mood regulation, energy levels, and muscle maintenance. A diet that significantly lowers androgenic activity over the long term could, in some individuals, lead to unintended consequences.

The literature on pharmaceutical 5-AR inhibitors, while involving much more potent effects, provides a useful model for understanding these potential systemic shifts. Reports of decreased libido, mood changes, and even metabolic alterations in some users of these medications highlight the interconnectedness of the endocrine system.

A dietary approach is far gentler, yet the principle remains the same ∞ altering one part of the hormonal network can create ripples throughout the entire system. Therefore, a balanced approach is key, focusing on whole foods and gentle modulation rather than extreme restriction or overconsumption of specific supplements.

The following table outlines some key dietary components with anti-androgenic properties and their mechanisms of action:

| Dietary Component | Primary Active Compound | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Primary Food Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Tea | Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | Inhibits 5-alpha reductase; may increase SHBG | Brewed green tea, matcha |

| Soy | Isoflavones (e.g. genistein, daidzein) | Binds to estrogen receptors; increases SHBG | Tofu, tempeh, edamame, soy milk |

| Flaxseed | Lignans | Increases SHBG; inhibits 5-alpha reductase | Ground flaxseed, flaxseed oil |

| Pumpkin Seeds | Zinc, Delta-7-sterine | Inhibits 5-alpha reductase | Raw or roasted pumpkin seeds |

| Spearmint | Carvone, Rosmarinic acid | Reduces free testosterone levels | Spearmint tea |

| Reishi Mushroom | Triterpenoids | Inhibits 5-alpha reductase | Dietary supplements, extracts |

This intermediate understanding moves the conversation from the general to the specific. It empowers you to make targeted dietary choices based on the biochemical effects of individual foods, while keeping the broader, systemic implications in view. This is the foundation of a truly personalized and sustainable wellness protocol.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term effects of anti-androgenic diets requires a shift in perspective from dietary components to the body’s complex, adaptive regulatory systems. Sustained nutritional pressure on the endocrine system does not occur in a vacuum.

The body’s homeostatic mechanisms, governed primarily by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, will respond to chronic modulation of androgen synthesis and signaling. Understanding the potential for these compensatory adaptations, as well as the unintended consequences on interconnected systems like metabolic and neurological health, is essential for a comprehensive assessment of such a dietary strategy over a lifespan.

What Are the Unintended Consequences for Systemic Metabolic Function?

While the primary goal of an anti-androgenic diet may be to influence hair follicles, the systemic nature of androgens means that long-term modulation can have profound effects on whole-body metabolism. Androgens are powerful anabolic hormones, playing a critical role in maintaining lean muscle mass, regulating fat distribution, and influencing insulin sensitivity. Chronically dampening their effects, even through gentle dietary means, warrants a detailed examination of the potential metabolic sequelae.

Androgens and Insulin Sensitivity

The relationship between androgens and metabolic health is intricate. Testosterone has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. It promotes the uptake and utilization of glucose, contributing to stable blood sugar levels. The conversion of testosterone to DHT is one part of this signaling cascade.

The literature surrounding pharmaceutical 5-alpha reductase inhibitors offers a valuable, if amplified, model for these effects. Some studies on men using finasteride have indicated the development of hepatic insulin resistance and increased lipid accumulation in the liver. This suggests that a significant, long-term reduction in DHT could interfere with the liver’s ability to properly process glucose and fats.

While a dietary approach is far less potent, the biological principle holds. A diet that consistently and effectively reduces 5-AR activity over many years could subtly shift an individual’s metabolic profile, potentially reducing their insulin sensitivity and altering lipid metabolism in ways that are clinically significant over time.

Impact on Body Composition and Skeletal Health

The anabolic properties of androgens are fundamental to the maintenance of muscle mass and bone mineral density. Testosterone directly stimulates protein synthesis in muscle cells and promotes the proliferation of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for building new bone. Any long-term strategy that reduces the bioavailability or action of androgens must be considered in this context.

A sustained dietary regimen that significantly lowers free testosterone or DHT could, over a period of years or decades, contribute to a gradual decline in lean body mass and a potential increase in adiposity. Furthermore, the connection between androgens and bone health is critical.

While estrogen is the primary hormonal regulator of bone density in women, androgens play a crucial supportive role in both sexes. Research has suggested a potential link between 5-AR inhibitor use and altered bone metabolism. This raises a valid question about whether a highly effective, long-term anti-androgenic diet could become a contributing factor to osteopenia or osteoporosis later in life, particularly in individuals with other risk factors.

The body’s response to chronic hormonal modulation is a dynamic process, involving feedback loops and systemic adaptations that extend far beyond the initial target tissue.

Neurosteroids and the Central Nervous System

The brain is a major target for sex hormones. Testosterone, DHT, and their metabolites are classified as neurosteroids, actively synthesized within the central nervous system and exerting powerful effects on neuronal function, mood, and cognition. The 5-alpha reductase enzyme is highly active in various brain regions, and the DHT produced locally is a key regulator of neurotransmitter systems, including GABAergic and dopaminergic pathways. This is the biological basis for the mood and libido-regulating effects of androgens.

The discussion around Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS), a constellation of persistent side effects including depression, anxiety, and cognitive complaints reported by some men after ceasing the medication, has brought the role of neurosteroids into sharp focus. While the condition is controversial and its mechanisms are still being investigated, it highlights the potential for profound neurological consequences when the 5-AR pathway is significantly altered.

A long-term dietary strategy that successfully inhibits this enzyme could have subtle, cumulative effects on neurosteroid balance. Over years, this could manifest as gradual shifts in mood, a blunting of libido, or changes in cognitive function that the individual may not immediately associate with their dietary choices.

This is not to suggest that eating pumpkin seeds will induce a clinical syndrome; rather, it is a call to respect the profound interconnectedness of our biological systems. The same pathway that influences a hair follicle on the scalp is also active in the circuits that govern our mental and emotional well-being.

The Gut Microbiome a Personalized Mediator

A complete academic analysis must also consider the role of the gut microbiome as a critical variable in mediating the effects of an anti-androgenic diet. The bioavailability and metabolic activity of many phytoestrogens are entirely dependent on their processing by intestinal bacteria.

For example, the soy isoflavone daidzein is converted into equol, a far more potent phytoestrogen, by certain species of gut bacteria. However, only about 30-50% of the Western population possesses the specific bacterial strains capable of this conversion. This means that two individuals consuming the exact same soy-rich diet could experience vastly different hormonal effects.

One may produce significant amounts of equol and see a measurable increase in SHBG and a decrease in free androgens, while the other may experience minimal hormonal change. This “equol producer” status is a key determinant of the efficacy of a soy-based anti-androgenic strategy and highlights the limitations of making broad dietary recommendations without considering individual biology.

This principle extends to other plant compounds, where the microbiome acts as a personalized chemical processing plant, determining the ultimate impact of the foods we consume.

The table below summarizes potential long-term systemic considerations of a sustained and effective anti-androgenic dietary protocol.

| System | Potential Long-Term Effect | Underlying Biological Mechanism | Level of Evidence (from dietary studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | Altered insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism | Reduced androgenic stimulation of glucose uptake in muscle; potential for increased hepatic lipid storage. | Low to Moderate (Inferred from pharmaceutical models) |

| Skeletal | Gradual reduction in bone mineral density | Decreased androgen-mediated stimulation of osteoblast activity and bone formation. | Low (Theoretical, with some support from pharmaceutical data) |

| Neurological | Subtle shifts in mood, libido, and cognition | Alteration in the balance of neurosteroids (e.g. allopregnanolone, DHT) in the central nervous system. | Low (Inferred from pharmaceutical models and mechanism) |

| Endocrine | Compensatory changes in the HPG axis | Potential for upregulation of 5-AR or changes in LH/FSH signaling to maintain homeostasis. | Theoretical (Based on endocrine principles) |

| Reproductive | Potential changes in fertility parameters | Androgens are essential for spermatogenesis in men and follicular development in women. | Low (Primarily from high-dose supplement studies) |

In conclusion, a sophisticated view of anti-androgenic diets acknowledges them as a form of long-term, low-dose endocrine modulation. While potentially beneficial for their intended purpose of preserving hair, their effects are systemic.

The true long-term outcome for any given individual is a complex interplay between the specific dietary components chosen, their genetic predispositions, their metabolic health, and the unique composition of their gut microbiome. A responsible, long-term approach requires an awareness of these interconnected systems and a commitment to monitoring overall health, not just the changes observed in the mirror.

References

- Grant, Paul. “Spearmint herbal tea has significant anti-androgen effects in polycystic ovarian syndrome. A randomized controlled trial.” Phytotherapy research, vol. 24, no. 2, 2010, pp. 186-8.

- Zararsiz, I. et al. “Adverse Effects and Safety of 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride) ∞ A Systematic Review.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, vol. 31, no. 6, 2017, pp. 952-962.

- Traish, Abdulmaged M. “Post-finasteride syndrome ∞ a surmountable challenge for clinicians.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 113, no. 1, 2020, pp. 21-50.

- Akdoğan, M. et al. “Effect of spearmint (Mentha spicata Labiatae) teas on androgen levels in women with hirsutism.” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 21, no. 5, 2007, pp. 444-7.

- Said, Mohammed A. and Akanksha Mehta. “The Impact of 5α-Reductase Inhibitor Use for Male Pattern Hair Loss on Men’s Health.” Current Urology Reports, vol. 19, no. 8, 2018, p. 65.

- Sizar, O. and Patrick M. Zito. “5 Alpha Reductase Inhibitors.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- Fabbri, Andrea, et al. “Finasteride and bone mineral density in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.” The Journal of Urology, vol. 170, no. 4, 2003, pp. 1259-62.

- Patel, D. P. and N. K. Swink. “Adverse effects and safety of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride, dutasteride) ∞ a systematic review.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 75, no. 2, 2016, pp. 269-74.

- Hamilton, James B. “Effect of castration in adolescent and young adult males upon further changes in the proportions of bare and hairy scalp.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 20, no. 10, 1960, pp. 1309-18.

- Goodarzi, Mark O. et al. “Androgen-responsive genes in plucked hair follicles for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 8, 2013, pp. 3399-406.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological terrain you are navigating. It details the pathways, signals, and systemic connections that govern not only the health of your hair but your overall vitality. This knowledge is a powerful tool, shifting your perspective from one of passive concern to one of active, informed participation in your own health.

You have seen how a single dietary choice can initiate a cascade of biochemical events, a testament to the profound communication that exists between what you consume and how your body functions.

Consider your own unique biology. Your genetic blueprint, your metabolic tendencies, and the specific environment within your body all contribute to how you will respond to any nutritional strategy. The path forward involves listening to your body’s feedback with a new level of understanding. The changes you feel, both positive and unexpected, are data points.

They are valuable pieces of information that can guide your journey. This process of self-discovery, of connecting the science to your lived experience, is the core of personalized wellness. The ultimate goal is to cultivate a state of health that is not defined by a single outcome, but by a sense of integrated well-being, energy, and function across all of your body’s interconnected systems.