Fundamentals

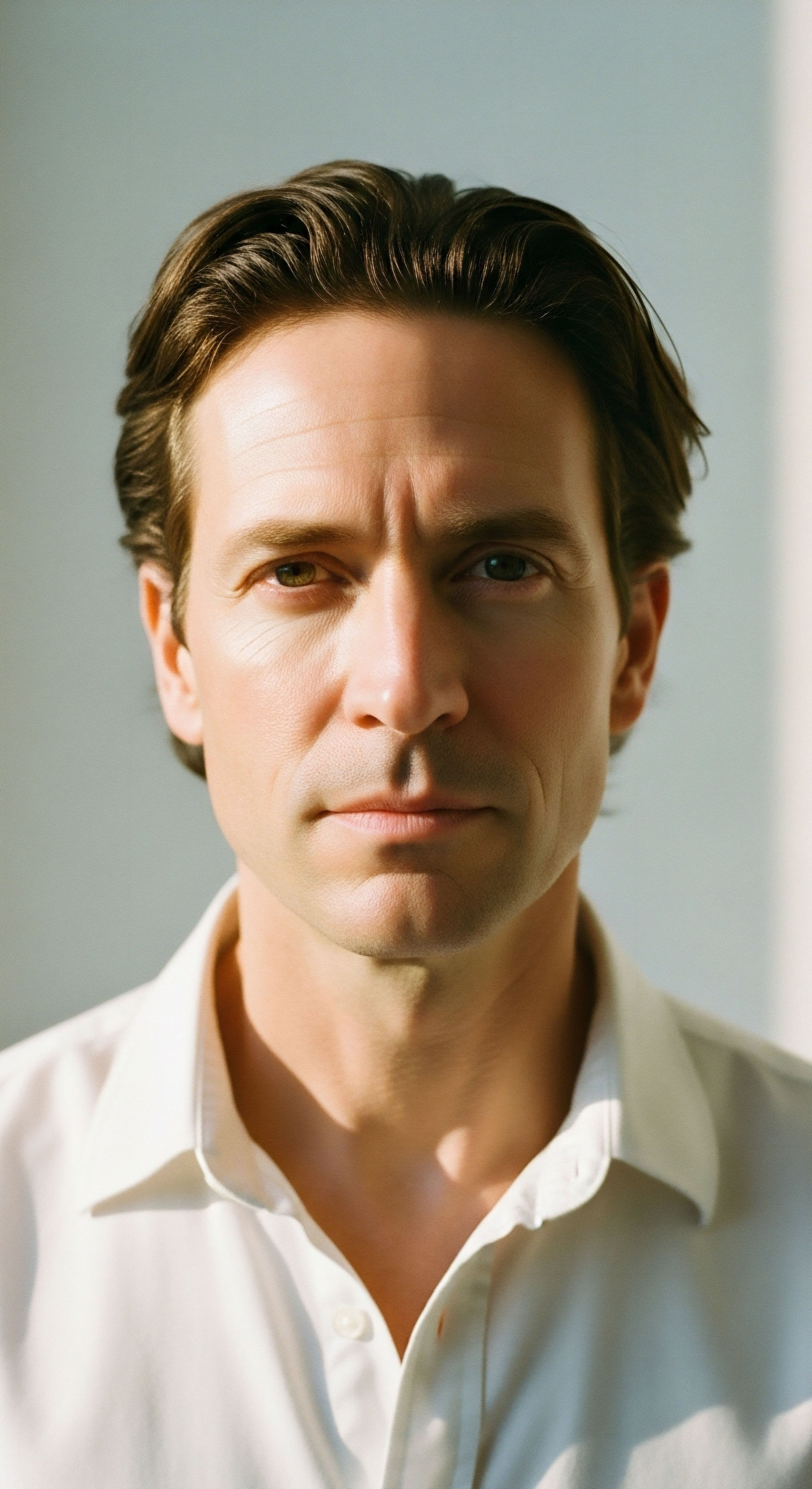

The feeling of being perpetually overwhelmed, as if constantly bracing for an impact that never arrives, is a deeply personal and physically draining experience. This sensation is your body’s internal alarm system, a sophisticated survival mechanism, operating on overdrive.

Your lived reality of fatigue, mental fog, and a sense of running on empty is a direct reflection of a biological process that has become dysregulated. Understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality.

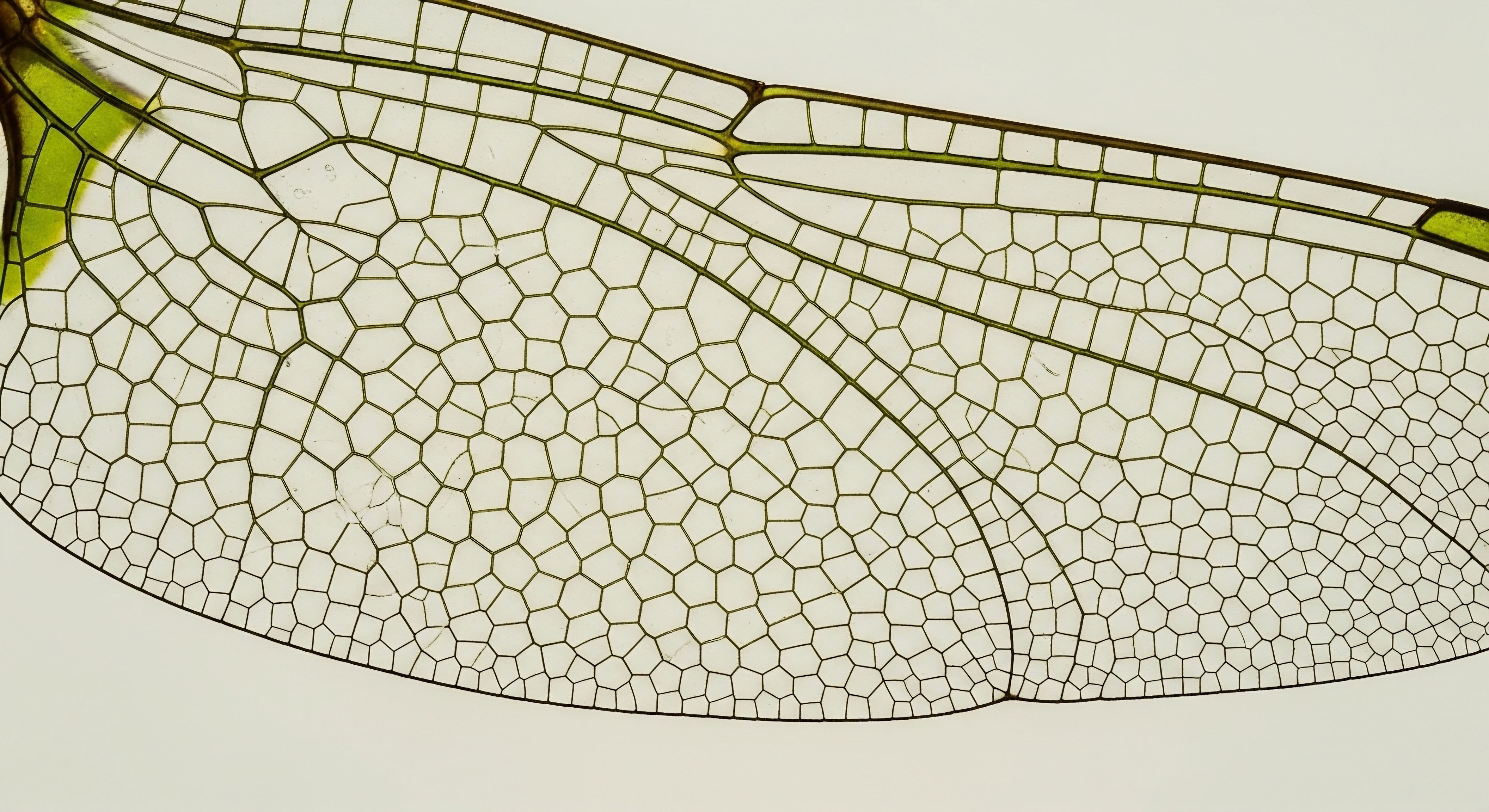

The body’s response to any perceived threat, whether a physical danger or a demanding work deadline, is orchestrated by a complex and elegant communication network known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. This system is designed for short, powerful bursts of activity, not for the relentless, low-grade pressure of modern life.

When your brain perceives a stressor, it signals the hypothalamus to release a hormone, which in turn instructs the pituitary gland to send another signal down to your adrenal glands. This final step culminates in the release of cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. Cortisol is a powerful agent of mobilization.

It increases blood sugar for immediate energy, sharpens your focus, and prepares your muscles for a “fight or flight” response. In a balanced system, once the threat passes, cortisol levels recede, and the body returns to a state of equilibrium. This is a perfect, life-sustaining design for acute situations. The architecture of this system is meant to be an occasional expenditure of resources, a temporary state of high alert from which the body can recover and rebuild.

Unmanaged physiological pressure forces the body’s emergency systems into continuous operation, disrupting the natural rhythms of hormonal communication.

The Cortisol Cascade

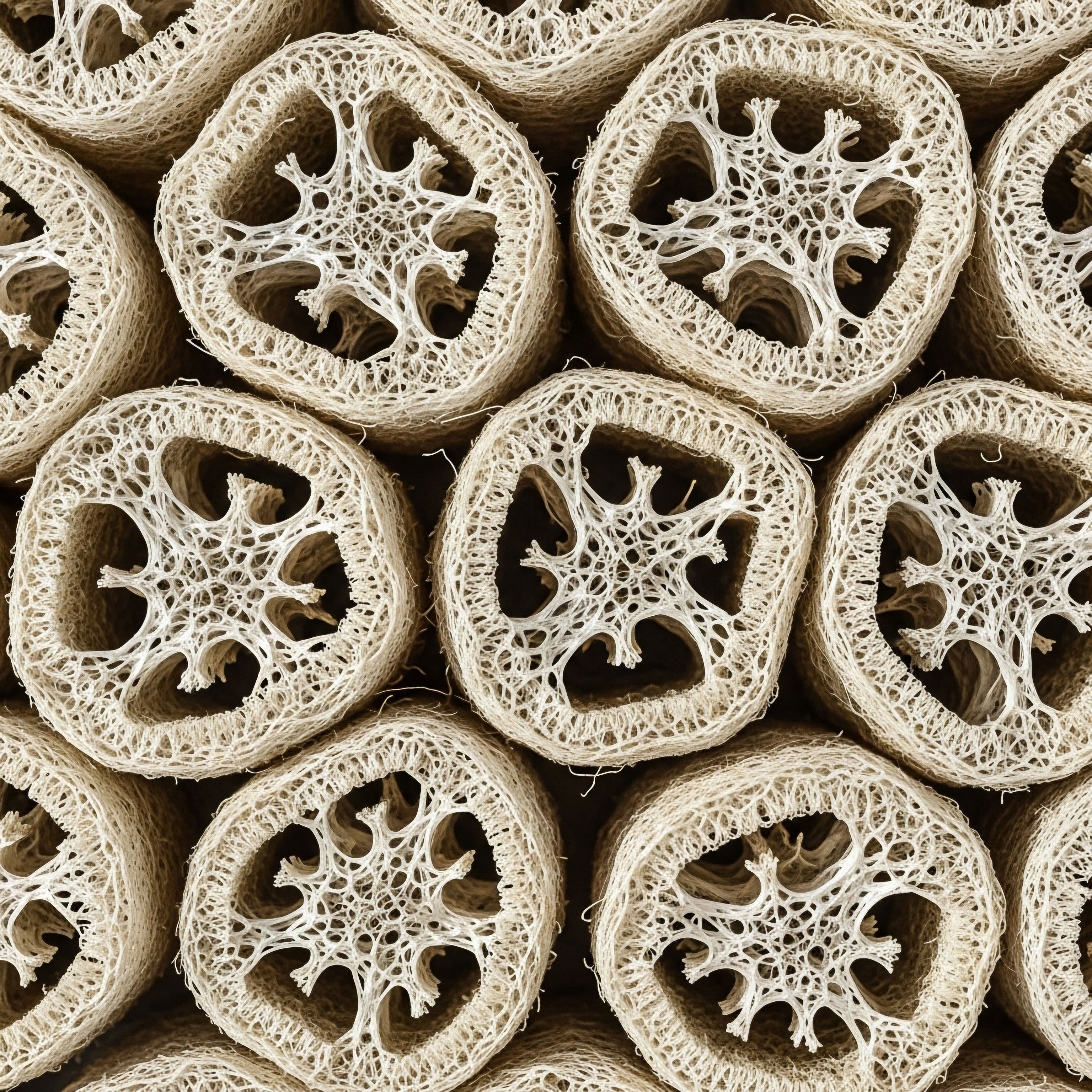

When the “off” switch for this stress response is rarely flipped, the consequences begin to cascade through your entire physiology. Continuous signaling taxes the adrenal glands, demanding a constant output of cortisol. Your body, in its attempt to adapt to this unending state of emergency, begins to make difficult choices.

Resources are diverted away from what it deems non-essential long-term projects, such as reproductive health, tissue repair, and robust immune function, to fuel the immediate crisis. This is the biological basis for why you may feel depleted; your body is allocating its energy reserves to a perceived threat that never subsides. The persistent elevation of cortisol fundamentally alters the chemical environment of your body, initiating a series of downstream effects that touch nearly every aspect of your health.

How Does the Endocrine System Respond to Constant Pressure?

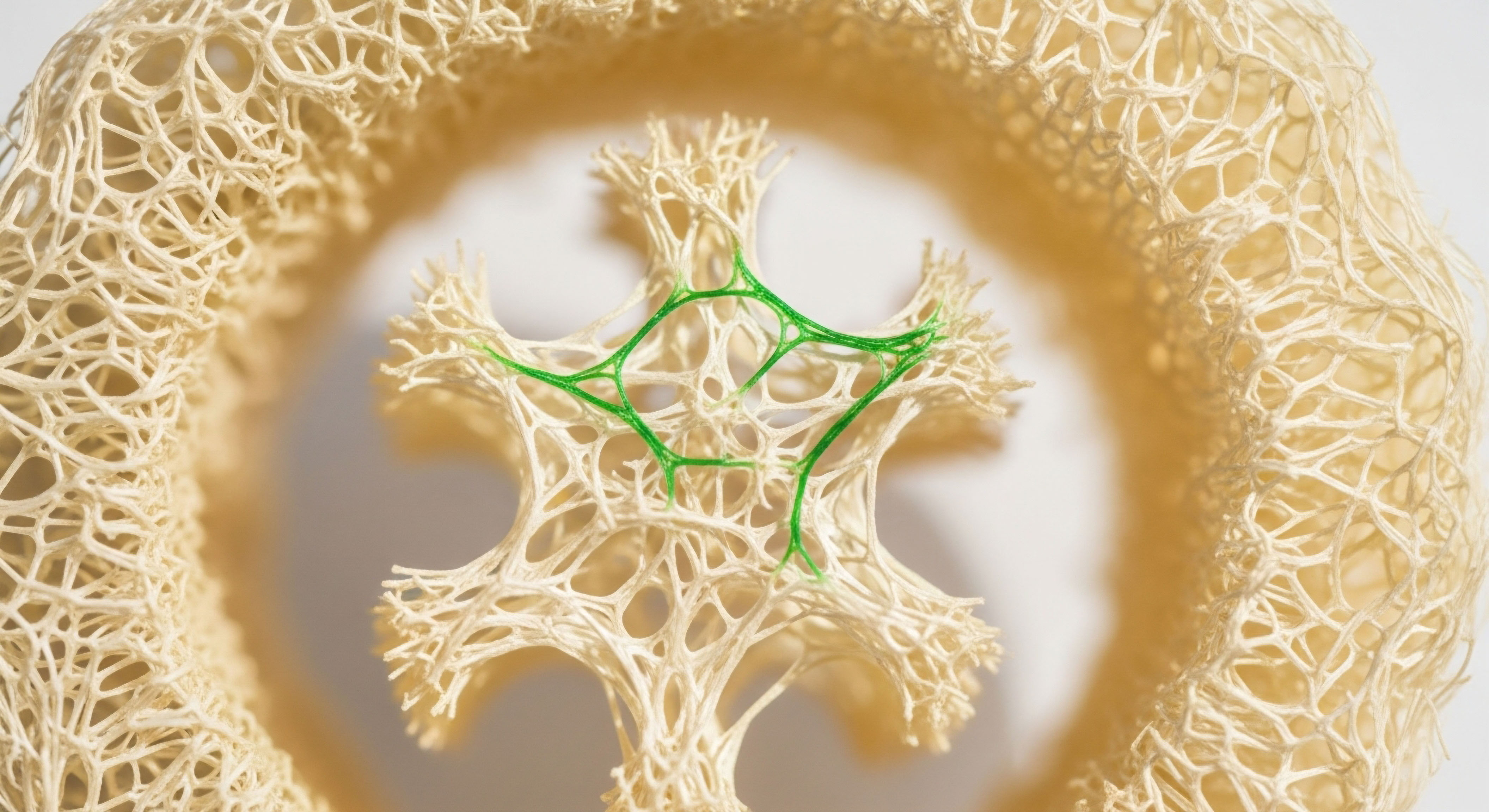

The endocrine system is a network of glands that produce and secrete hormones, the chemical messengers that regulate everything from your metabolism and growth to your mood and sleep cycles. These glands communicate in a finely tuned feedback loop, where the output of one hormone influences the production of another.

Chronic stress introduces a powerful, disruptive signal into this delicate conversation. The HPA axis, when perpetually activated, begins to dominate the conversation, shouting over the quieter signals from other essential endocrine glands like the thyroid and gonads. This creates a state of systemic miscommunication, where the body’s carefully calibrated internal rhythms are thrown into disarray.

The long-term result is a slow erosion of function, a gradual decline in the efficiency of the very systems that create health and vitality.

Intermediate

The transition from an acute stress response to a state of chronic endocrine dysregulation is a gradual process of maladaptation. The body’s systems, designed for precision and balance, begin to operate under a new set of rules dictated by continuous physiological pressure.

This recalibration has profound and specific consequences for key hormonal axes beyond the HPA system, directly impacting metabolic rate, reproductive health, and growth processes. Understanding these specific disruptions is critical to connecting your symptoms to their underlying endocrine roots and appreciating the rationale behind targeted therapeutic interventions.

Thyroid and Metabolic Slowdown

Your thyroid gland acts as the metabolic thermostat for your body, regulating the speed at which your cells convert fuel into energy. The elevated levels of cortisol associated with chronic stress directly interfere with this process. Cortisol can inhibit the conversion of the inactive thyroid hormone T4 into the active form, T3.

This means that even if your thyroid is producing enough T4, your body cannot effectively use it. The result is a condition sometimes referred to as functional hypothyroidism, where lab tests for primary thyroid function might appear normal, yet you experience all the symptoms of an underactive thyroid ∞ persistent fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and mental sluggishness.

Furthermore, sustained cortisol can increase levels of reverse T3 (rT3), a molecule that blocks T3 from binding to its receptors, effectively putting the brakes on your metabolism. This is a protective mechanism in the short term, designed to conserve energy during a crisis. When the crisis becomes chronic, this protective mechanism becomes a primary driver of metabolic dysfunction.

Disruption of the Reproductive Axis

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis governs reproductive function in both men and women. This system is particularly sensitive to the presence of chronic stress. The body, prioritizing survival over procreation, will downregulate the HPG axis when under duress. The same precursor molecules used to create sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen are also used to produce cortisol.

In a state of high demand for cortisol, the body shunts these resources away from hormone production, a phenomenon known as “pregnenolone steal.”

Consequences for Male Hormonal Health

In men, chronic stress directly suppresses the signals from the pituitary gland that stimulate testosterone production in the testes. This leads to a decline in circulating testosterone levels, manifesting as symptoms of low libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of muscle mass, increased body fat, and profound fatigue.

This state is clinically recognized as hypogonadism and often requires a comprehensive approach to restore function. Protocols involving Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), often using Testosterone Cypionate, are designed to restore optimal physiological levels. Supporting medications like Gonadorelin may be used to maintain the body’s own signaling pathways to the testes, preserving natural function and fertility. Anastrozole is sometimes included to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, preventing potential side effects and maintaining a balanced hormonal profile.

Consequences for Female Hormonal Health

In women, the disruption of the HPG axis is equally significant. Chronic stress can lead to irregular menstrual cycles, anovulation (cycles where no egg is released), and worsening of premenstrual symptoms. For women in the perimenopausal transition, a time already characterized by fluctuating hormones, chronic stress can dramatically amplify symptoms like hot flashes, sleep disturbances, and mood swings.

The body’s diminished capacity to produce progesterone and maintain estrogen balance is exacerbated by high cortisol levels. Therapeutic protocols for women often focus on restoring this balance. This may involve low-dose Testosterone Cypionate to address energy, libido, and cognitive function, alongside progesterone to stabilize the menstrual cycle and improve sleep. These hormonal optimization strategies are designed to provide the stability the HPG axis can no longer maintain on its own.

Chronic physiological pressure systematically dismantles endocrine balance, forcing a shift from long-term health and reproduction to short-term survival.

| Hormonal Axis | Primary Glands Involved | Key Hormones Affected | Long-Term Consequences of Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Adrenals | Cortisol, CRH, ACTH | Adrenal fatigue, immune suppression, cortisol resistance, metabolic syndrome. |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid (HPT) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Thyroid | TSH, T4, T3 | Impaired T4 to T3 conversion, increased reverse T3, slowed metabolism, fatigue, weight gain. |

| Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) | Hypothalamus, Pituitary, Gonads (Testes/Ovaries) | Testosterone, Estrogen, Progesterone, LH, FSH | Decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, irregular cycles, infertility, muscle loss. |

| Growth Hormone Axis | Hypothalamus, Pituitary | Growth Hormone (GH), GHRH | Decreased GH secretion, impaired tissue repair, muscle loss, altered body composition. |

Academic

The progression from chronic physiological pressure to systemic endocrine pathology is underpinned by complex molecular and cellular adaptations. At an academic level, the consequences are understood as a loss of regulatory integrity, primarily through the mechanisms of receptor downregulation and chronic low-grade inflammation.

The persistent elevation of cortisol and catecholamines initiates a cascade that not only disrupts hormonal signaling but also fundamentally alters the body’s metabolic and immune landscapes. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle where the consequences of stress generate further physiological stress, leading to conditions like metabolic syndrome, neuroinflammation, and accelerated cellular aging.

The Pathophysiology of Cortisol Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome

Initially, the body responds to high cortisol by increasing glucose availability. Over time, to protect themselves from the relentless signaling, insulin and cortisol receptors on cells become less sensitive. This phenomenon, known as receptor downregulation or resistance, is a critical turning point. When cells become resistant to insulin, the pancreas compensates by producing more, leading to hyperinsulinemia.

This combination of high blood glucose and high insulin is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that dramatically increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Concurrently, cortisol resistance means that the hormone’s anti-inflammatory properties become less effective.

The immune system, no longer properly regulated by cortisol, can become chronically activated, leading to a state of systemic low-grade inflammation. This inflammatory state is itself a powerful driver of insulin resistance, creating a vicious cycle that is difficult to break.

How Does Neuroendocrine Disruption Affect Brain Health?

The brain is a primary target of chronic stress. The hippocampus, a region critical for memory and mood regulation, is rich in glucocorticoid receptors and is highly susceptible to the effects of prolonged cortisol exposure. Chronic stress can impair neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons) in the hippocampus and can even lead to atrophy of this vital brain region.

This contributes to the cognitive deficits ∞ the “brain fog” ∞ and mood disorders, such as anxiety and depression, that are so common in individuals under chronic physiological pressure. Furthermore, stress-induced changes in neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine disrupt the delicate chemical balance that governs mood, motivation, and executive function.

Peptide therapies, such as those involving Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, are sometimes explored in this context. These protocols are designed to stimulate the natural production of Growth Hormone, which has neuroprotective properties and can help counteract some of the catabolic effects of chronic stress on brain and body tissues.

At a cellular level, chronic stress induces a state of receptor resistance and low-grade inflammation, driving the development of systemic metabolic and neuroendocrine disease.

This systemic inflammation also has profound implications for the vascular system. It promotes the development of atherosclerosis, where inflammatory plaques build up in the arteries. The constant elevation of heart rate and blood pressure from stress hormones further damages the lining of the blood vessels, accelerating this process. This direct link between the endocrine stress response and cardiovascular pathology illustrates how a state of psychological or physiological pressure translates into life-altering physical disease.

- Systemic Inflammation ∞ Chronically elevated cortisol eventually leads to cortisol resistance, impairing its ability to suppress inflammation. This results in a low-grade, systemic inflammatory state that contributes to a wide range of chronic diseases.

- Metabolic Dysregulation ∞ The combination of insulin resistance and high circulating glucose levels directly promotes the development of metabolic syndrome, characterized by central obesity, high blood pressure, and dyslipidemia.

- Immune Impairment ∞ The communication between the HPA axis and the immune system becomes dysfunctional. While acute stress can enhance immune function, chronic stress leads to suppression of certain immune responses, increasing vulnerability to infections, while promoting inflammation in other areas.

- Neurotransmitter Imbalance ∞ The constant demand on the nervous system alters the production and sensitivity of key neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, directly impacting mood, focus, and sleep architecture.

| Biomarker Category | Specific Marker | Direction of Change | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal | Cortisol (Salivary/Urine) | Initially High, then Dysregulated (e.g. blunted morning peak) | Indicates HPA axis dysfunction and adrenal fatigue. |

| Hormonal | DHEA-S | Decreased | Reflects adrenal exhaustion and loss of anabolic signaling. |

| Metabolic | Fasting Insulin & Glucose | Increased | Indicates insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes. |

| Metabolic | HbA1c | Increased | Shows long-term elevated blood sugar levels. |

| Inflammatory | High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) | Increased | A key marker of systemic inflammation and cardiovascular risk. |

| Inflammatory | Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Increased | A pro-inflammatory cytokine linked to multiple chronic diseases. |

References

- Khanam, Sabina. “Impact of Stress on Physiology of Endocrine System and on Immune System ∞ A Review.” International Journal of Unani and Integrative Medicine, vol. 2, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1-5.

- American Psychological Association. “Stress effects on the body.” APA.org, 1 Nov. 2018.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. “Chronic stress puts your health at risk.” MayoClinic.org, 1 Aug. 2023.

- “How Does Chronic Stress Weaken the Endocrine System?” Invigor Medical, 21 May 2024.

- “How Unmanaged Stress Can Be Harmful to Your Health.” Find My Therapist, 28 Jul. 2020.

- McEwen, B. S. “Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation ∞ central role of the brain.” Physiological reviews, vol. 87, no. 3, 2007, pp. 873-904.

- Chrousos, G. P. “Stress and disorders of the stress system.” Nature reviews Endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 7, 2009, pp. 374-81.

Reflection

Charting Your Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map of the biological territory you may be navigating. It connects the subjective feelings of being worn down and out of sync to the objective, measurable processes occurring within your cells. This knowledge is the foundational tool for moving forward.

It allows you to reframe your experience, viewing your symptoms as signals from a body that is intelligently, if painfully, adapting to overwhelming circumstances. Your personal health journey is a unique narrative, and understanding the language of your own physiology is the essential first step. The path toward restoring balance begins with this deeper awareness, empowering you to ask more precise questions and seek out solutions that honor the intricate reality of your own biological system.

Glossary

endocrine system

chronic stress

hpa axis

hpg axis

pregnenolone steal

testosterone replacement therapy

hypogonadism

chronic physiological pressure

metabolic syndrome

cortisol resistance

insulin resistance

growth hormone