Fundamentals

You may feel it as a persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, or a frustrating inability to manage your weight despite adhering to a disciplined diet and exercise regimen. Perhaps it manifests as a fog that clouds your thinking, making focus a challenge. These experiences are not personal failings.

They are often the subjective, lived-in symptoms of a profound biological miscommunication occurring at the cellular level. This is the starting point for understanding impaired insulin receptor sensitivity. It begins with your body’s intricate system of communication, where the conversation between the hormone insulin and your cells begins to break down. This process is central to your energy, your vitality, and your long-term health.

The Cellular Conversation

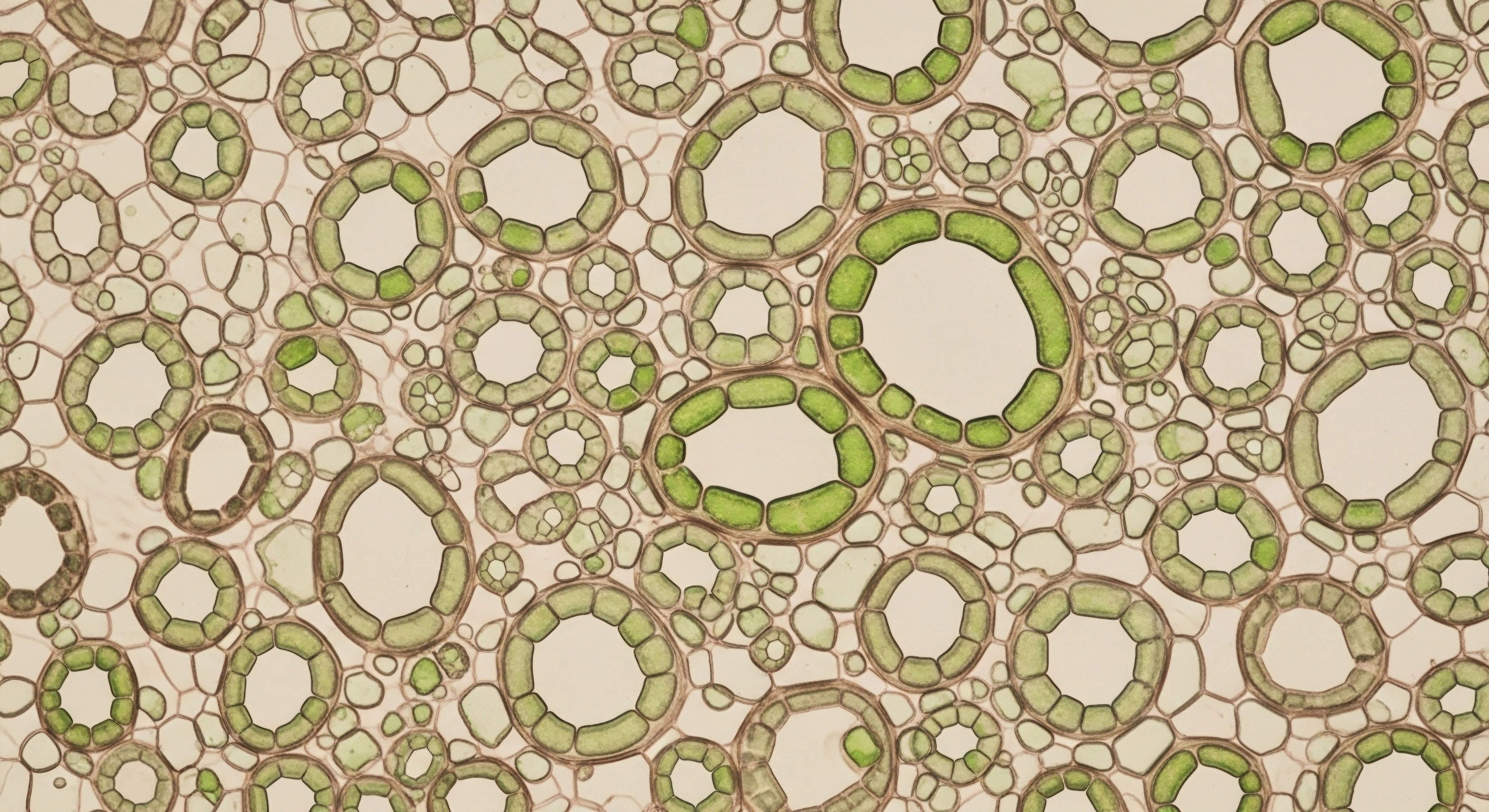

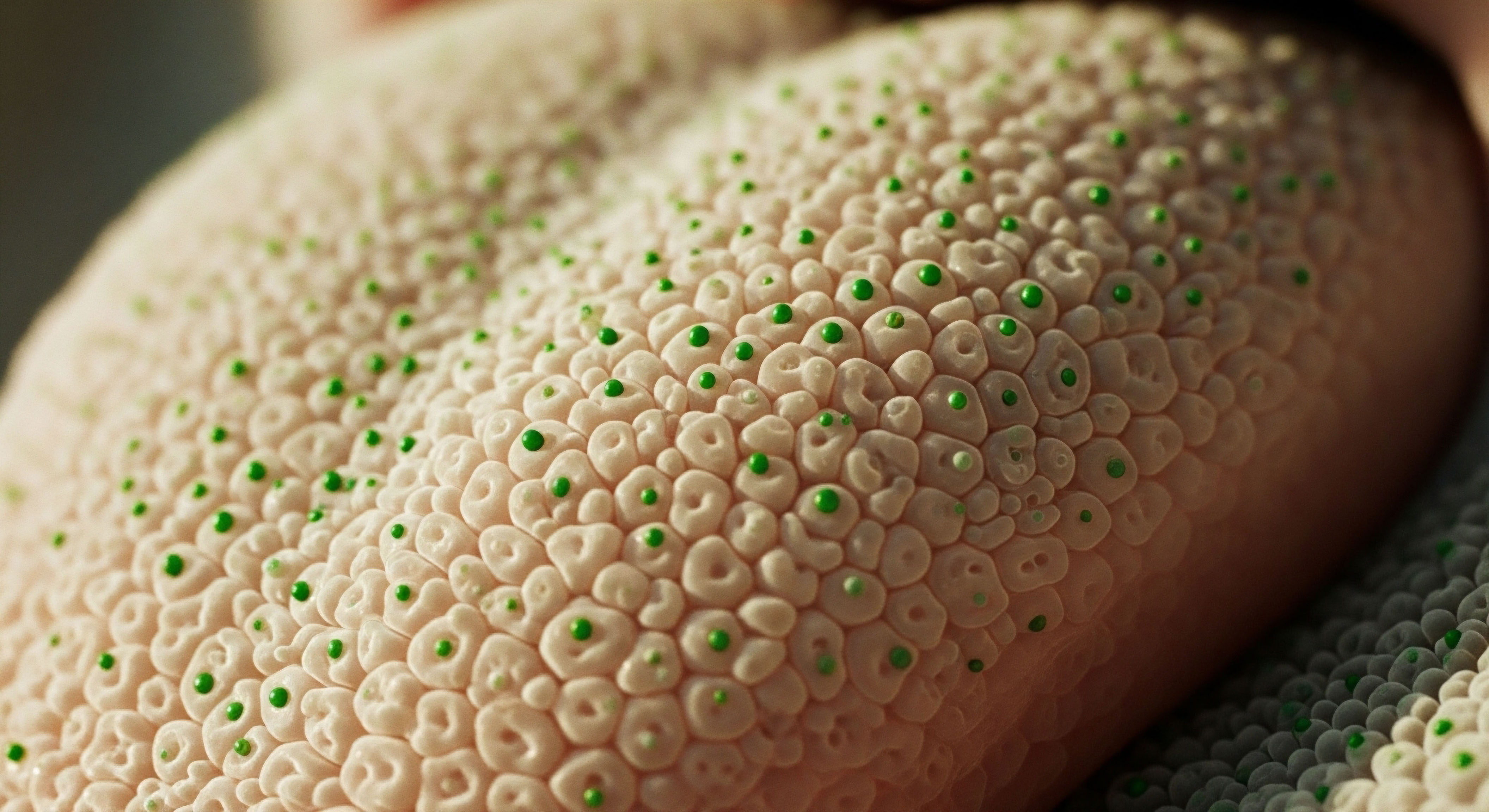

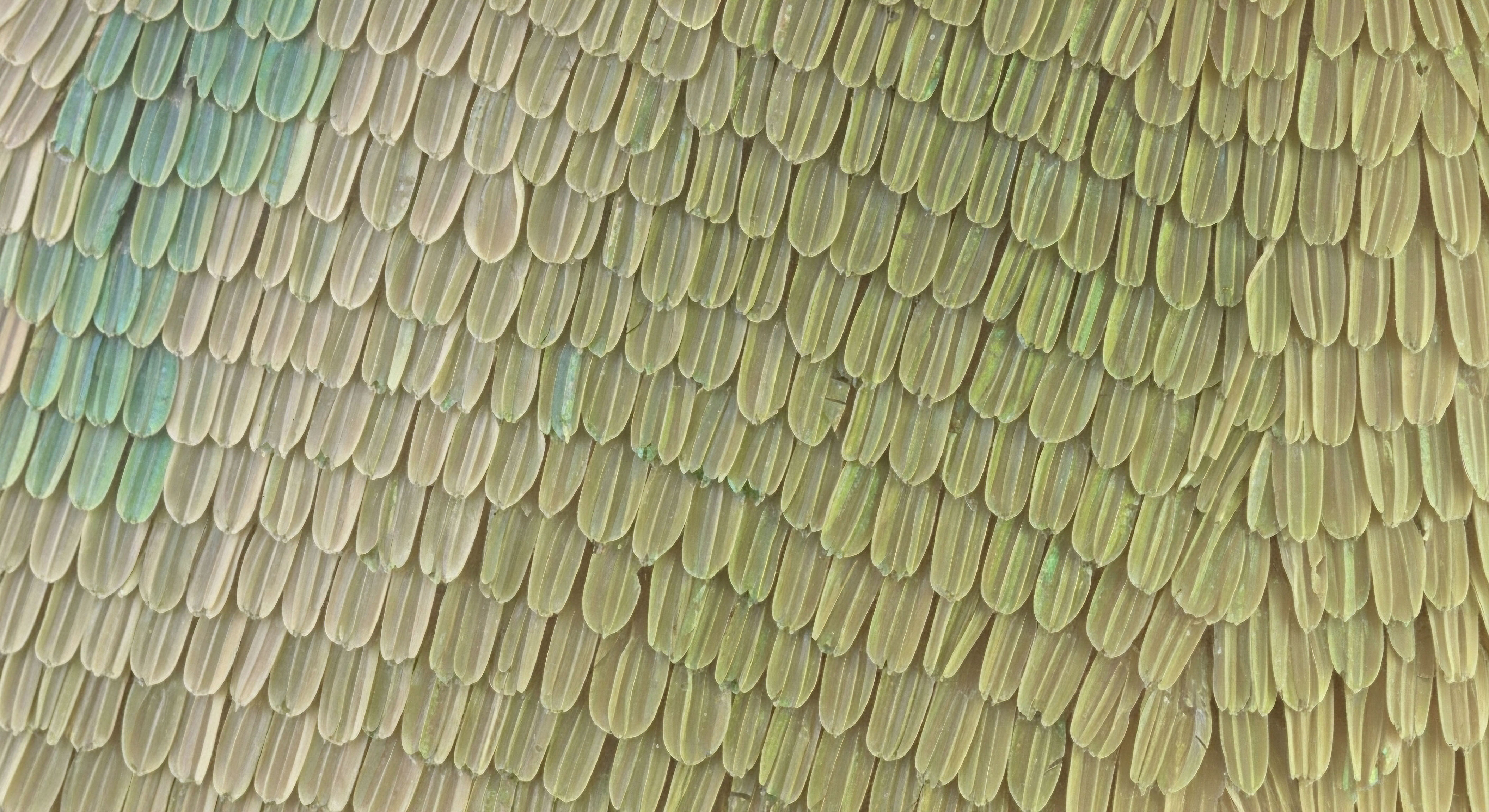

Every cell in your body requires energy to function, primarily in the form of glucose. Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, acts as the messenger that instructs cells to accept this fuel. Think of it as a highly specific key designed to fit a particular lock.

The insulin receptor, a protein structure on the surface of your cells, is this lock. When the key (insulin) fits perfectly into the lock (the receptor), a channel opens, and glucose passes from the bloodstream into the cell to be used for energy. This is a seamless, elegant process essential for life, governing how you store and use fuel from moment to moment. This system is designed for exquisite sensitivity and efficiency.

When the Message Is Lost

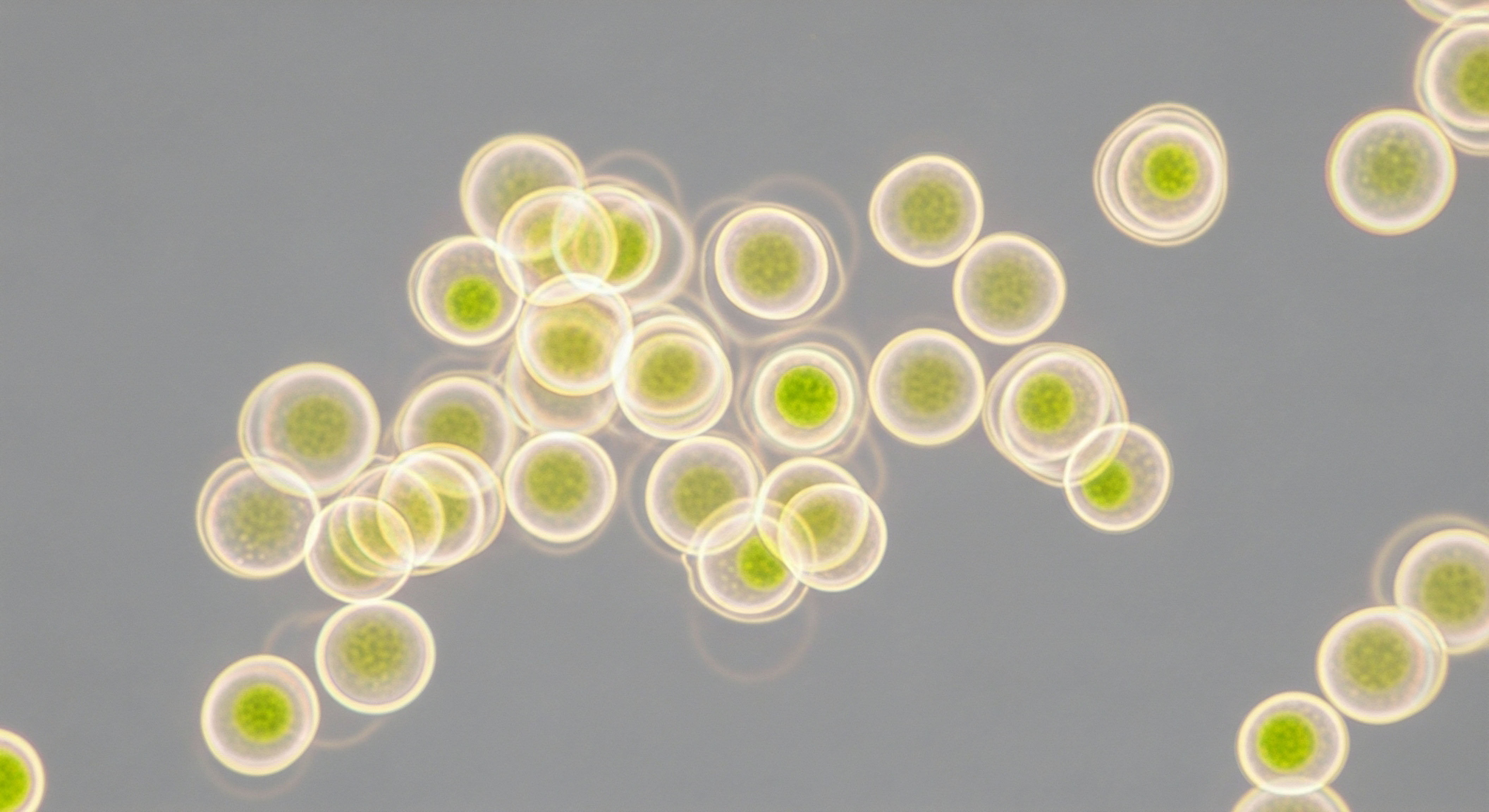

Impaired insulin receptor sensitivity describes a state where the lock becomes less responsive to the key. The cellular receptors begin to lose their affinity for insulin. The message to absorb glucose is sent, but it is not received clearly. The cell effectively becomes deaf to insulin’s signal.

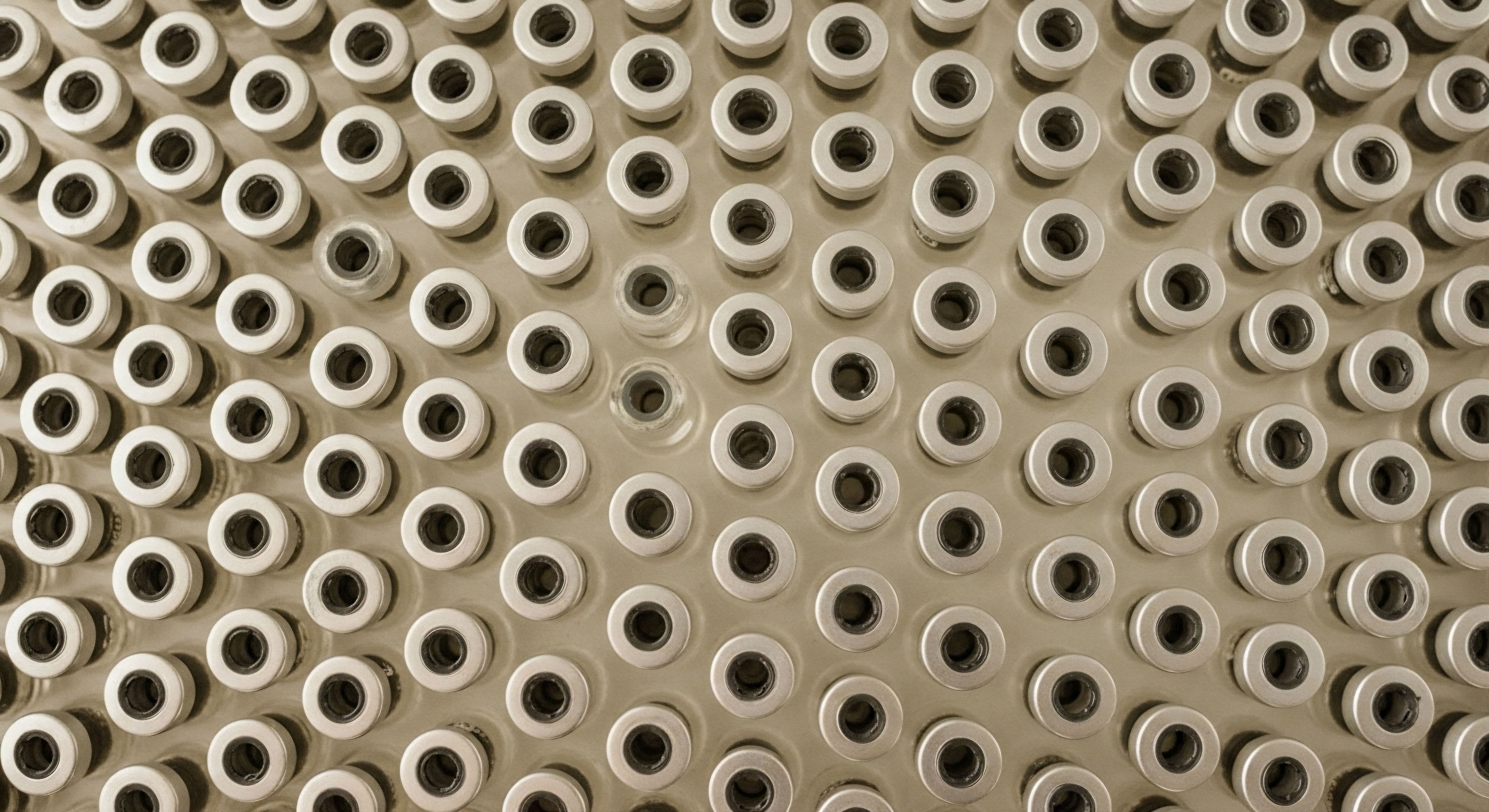

In response to this communication breakdown, the body’s innate intelligence initiates a compensatory measure. The pancreas, sensing that glucose levels in the blood remain high, works harder and produces even more insulin. It essentially “shouts” the message, hoping to force the unresponsive cells to listen.

This state of elevated insulin in the bloodstream is known as hyperinsulinemia. For a time, this strategy works. The sheer volume of insulin overcomes the resistance, and blood glucose levels may remain within a normal range. This compensatory phase can mask the underlying problem for years, while the high levels of insulin begin to exert their own systemic effects.

The initial stage of insulin resistance is characterized by the pancreas overproducing insulin to manage blood glucose, a state that precedes many clinical diagnoses.

What Is the Systemic Ripple Effect?

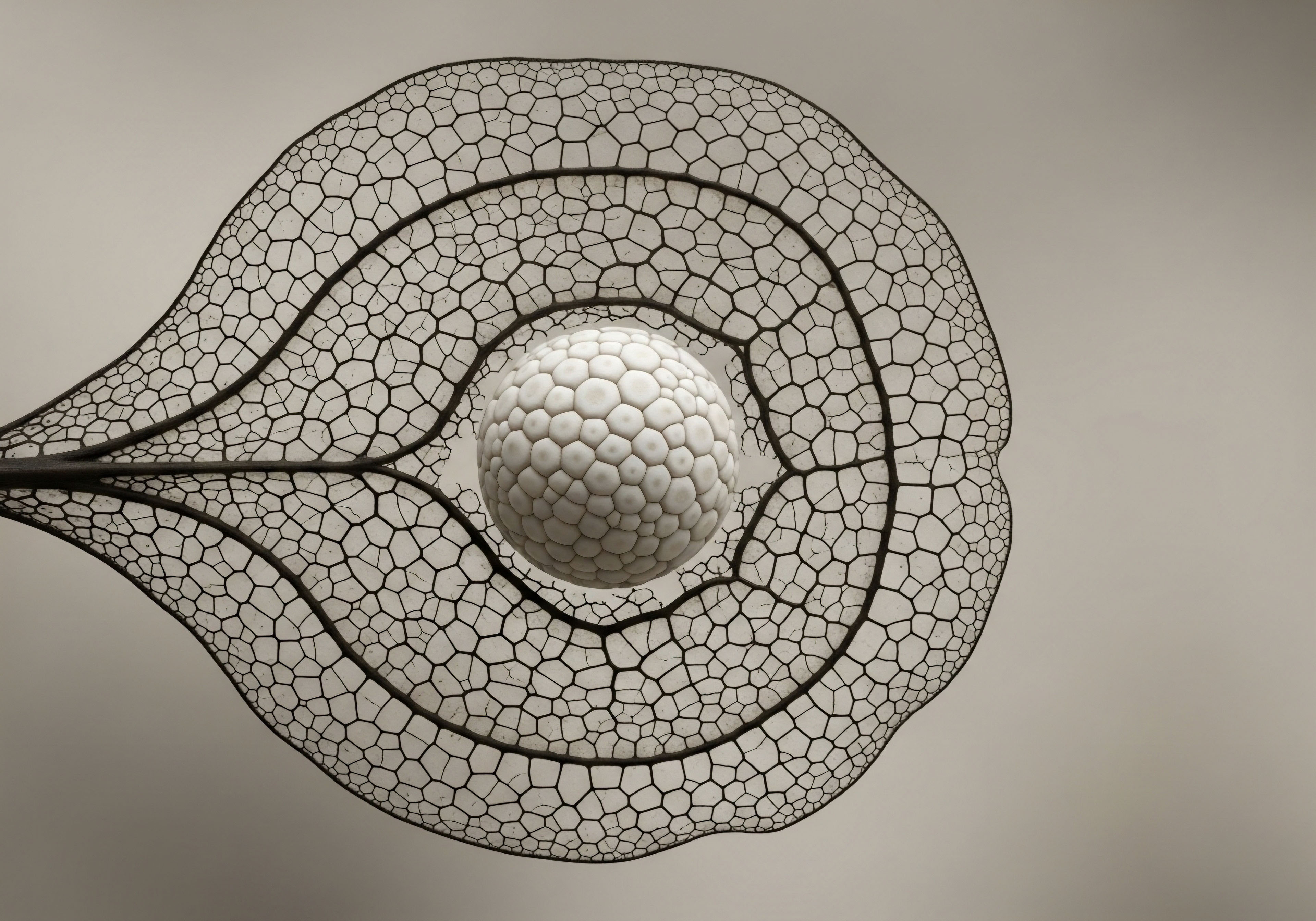

This persistent state of high insulin does not occur in a vacuum. Insulin is a powerful anabolic hormone, meaning its influence extends far beyond glucose regulation. It signals storage and growth throughout the body. When chronically elevated, it creates a cascade of effects that can alter other critical hormonal pathways and physiological processes.

The problem that began as a quiet miscommunication at a single receptor site ripples outward, impacting metabolic health, cardiovascular function, and even the delicate balance of sex hormones. Understanding these far-reaching consequences is the first step in recognizing that symptoms like fatigue or weight gain are signals from a body working diligently to manage a systemic imbalance. This provides a new framework for viewing your health, one centered on restoring the clarity of your body’s internal communication network.

- Hyperinsulinemia This is the condition of having excess levels of insulin circulating in the blood. It is a direct response to insulin resistance, as the pancreas attempts to compensate for the cells’ poor response to the hormone.

- Glucose Homeostasis This refers to the balance of insulin and glucagon to maintain blood glucose levels within a narrow, healthy range. Impaired receptor sensitivity directly disrupts this equilibrium.

- Metabolic Syndrome This is a cluster of conditions that occur together, increasing your risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. These conditions include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels. Insulin resistance is a core feature of this syndrome.

Intermediate

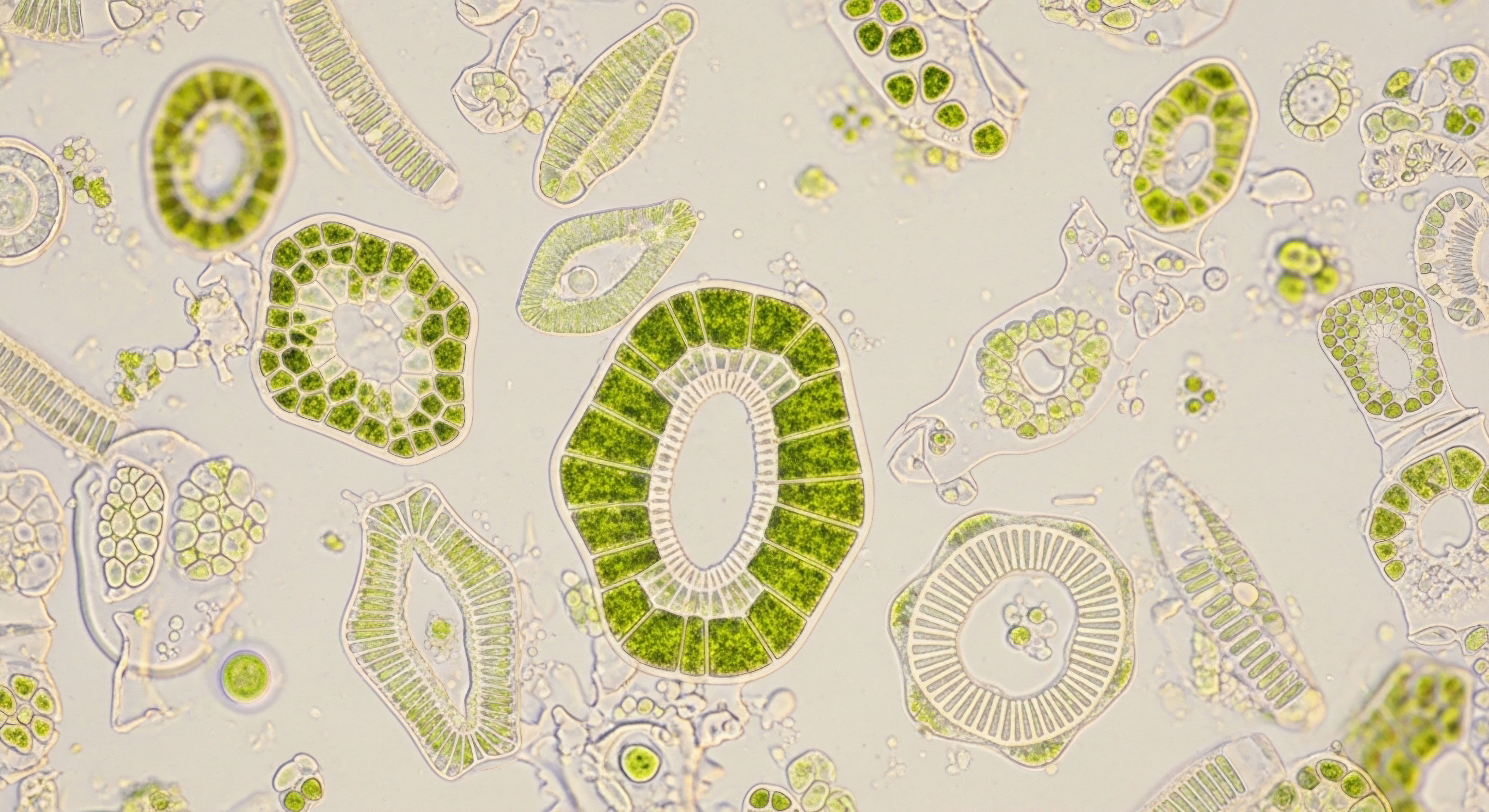

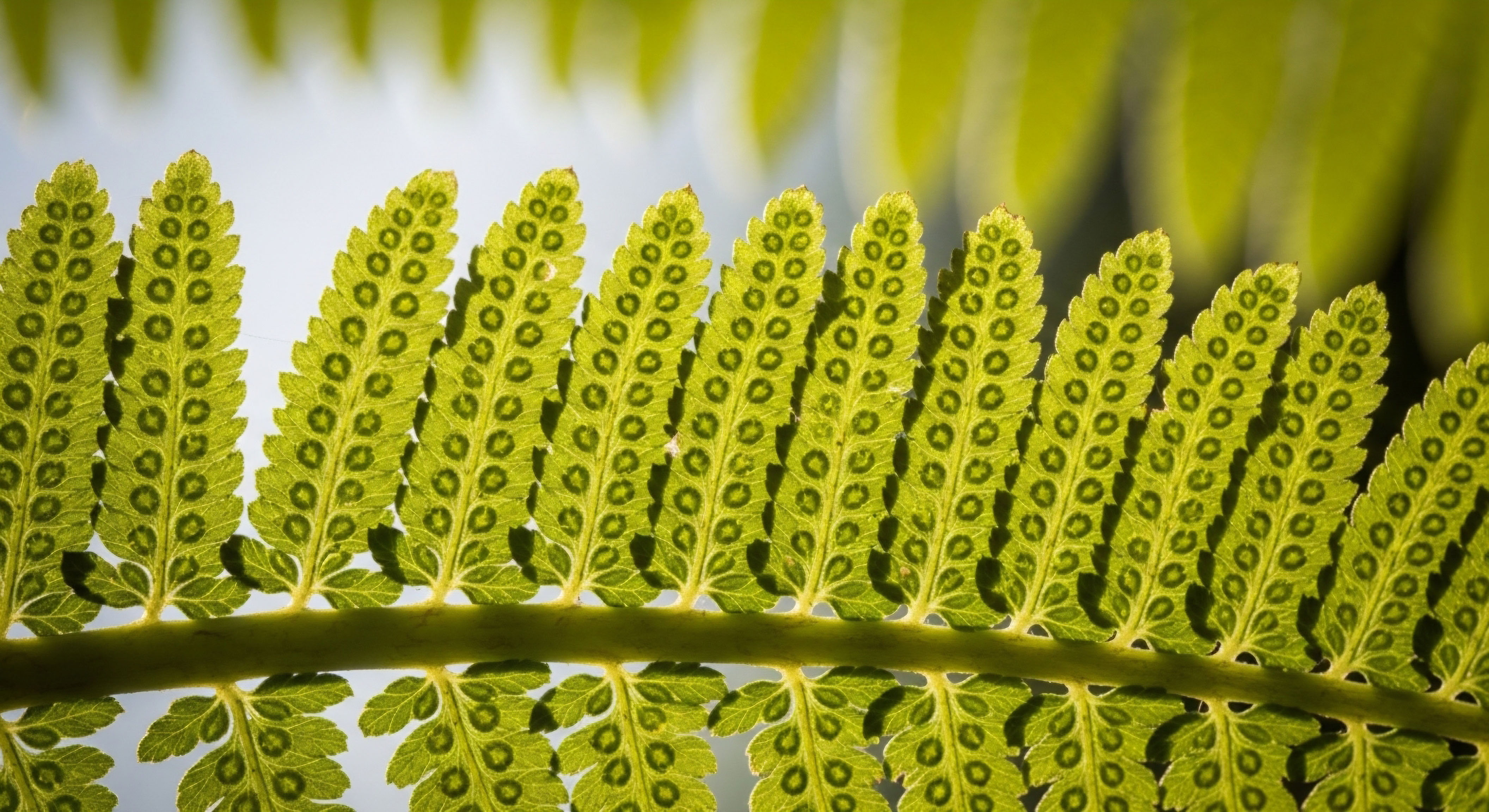

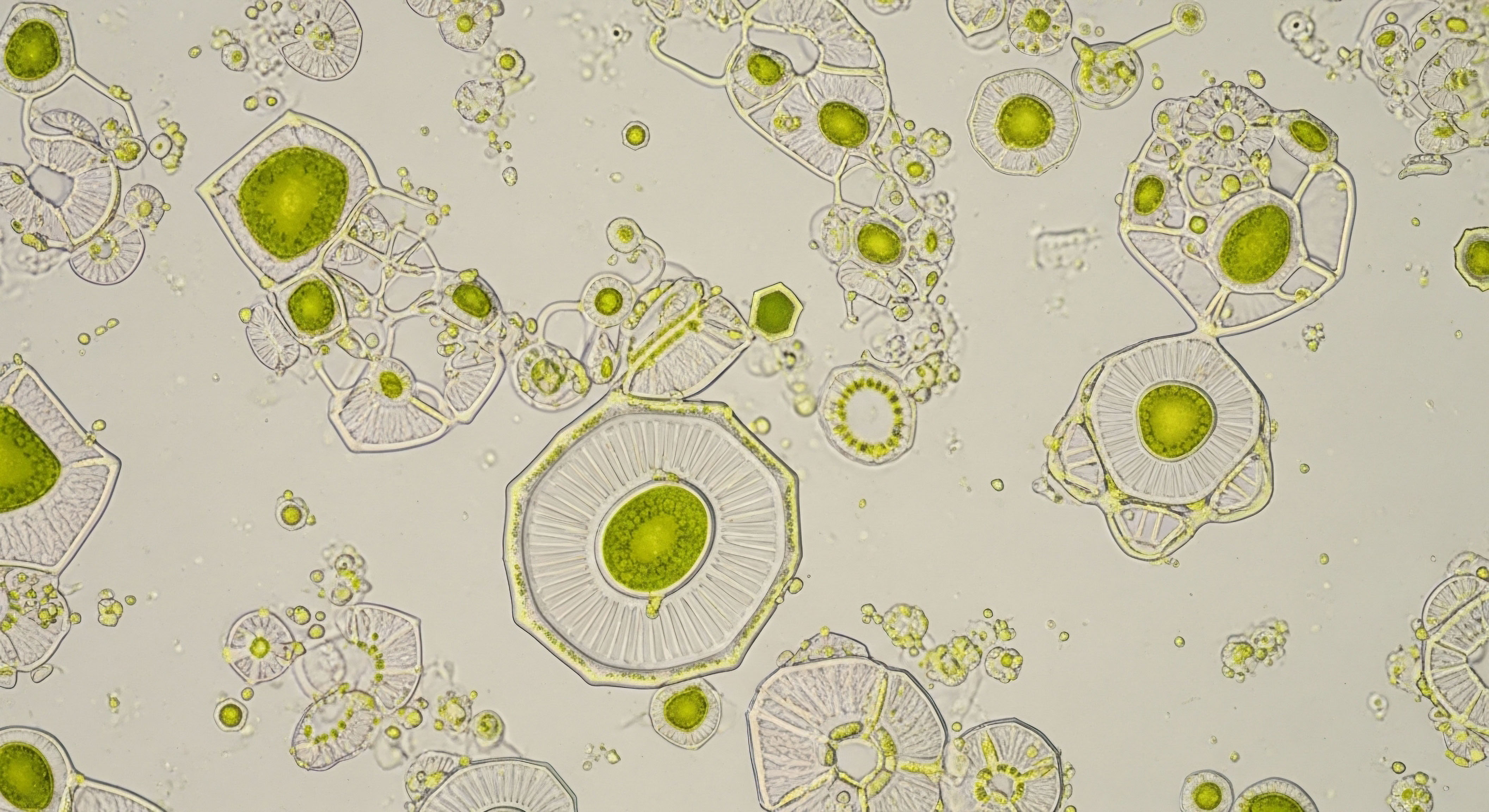

Moving beyond the initial concept of a communication breakdown, a deeper physiological exploration reveals how impaired insulin receptor sensitivity systematically dismantles metabolic health. When insulin binds to its receptor, it should trigger a complex intracellular signaling cascade. A key outcome of this cascade is the translocation of Glucose Transporter Type 4, or GLUT4, to the cell membrane.

GLUT4 is the actual channel through which glucose enters muscle and fat cells. In an insulin-resistant state, this signaling cascade is blunted. Fewer GLUT4 transporters make it to the cell surface, meaning the cell’s capacity to take up glucose is physically diminished. This molecular inefficiency is the engine driving the progression toward chronic disease.

The Progression to Systemic Disease

The body’s compensatory hyperinsulinemia, while temporarily effective at controlling blood sugar, becomes the primary driver of pathology over the long term. The constant exposure to high insulin levels and the eventual failure of the pancreas to keep up with demand lead to a predictable series of clinical consequences.

Metabolic and Endocrine Derangements

The most direct consequence is the development of type 2 diabetes. This occurs when the pancreatic beta-cells, exhausted from years of overproduction, can no longer produce enough insulin to overcome the resistance, leading to chronic hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). Concurrently, the liver’s function is altered.

In a healthy state, insulin tells the liver to stop producing glucose. When the liver becomes insulin resistant, it continues to release glucose into the bloodstream, even when levels are already high. It also begins converting excess sugar into fat through a process called de novo lipogenesis, leading directly to Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD).

How Does Insulin Resistance Affect Hormonal Balance?

The hormonal disturbances are particularly significant and often overlooked. Insulin resistance is deeply intertwined with the function of the endocrine system, creating imbalances that affect both men and women profoundly.

In women, high insulin levels can stimulate the ovaries to produce an excess of androgens, such as testosterone. This is a central mechanism in the pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), a condition characterized by irregular menstrual cycles, fertility challenges, and other metabolic issues. The hormonal imbalance driven by insulin resistance is a primary target for intervention in managing PCOS.

In men, the picture is equally complex. Insulin resistance contributes to lower testosterone levels through several mechanisms. It can impair the function of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the command-and-control system for sex hormone production.

Additionally, the increased body fat associated with insulin resistance, particularly visceral fat, leads to higher activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. This combination of reduced production and increased conversion creates a hormonal environment that favors lower testosterone and higher estrogen, contributing to symptoms of andropause.

Cardiovascular and Neurological Consequences

The cardiovascular system is exceptionally vulnerable to the effects of long-term insulin resistance. High insulin levels directly promote inflammation in the lining of the blood vessels (the endothelium), contributing to the development of atherosclerosis, or the hardening and narrowing of the arteries.

This state also leads to a characteristic lipid profile known as atherogenic dyslipidemia ∞ high triglycerides, low levels of protective HDL cholesterol, and an increase in small, dense LDL particles that are particularly damaging to arteries. Together with the high blood pressure that often accompanies this condition, these factors create a potent combination of risks for heart attack and stroke.

Recent research also highlights the connection between insulin resistance and brain health. The brain is a highly metabolic organ that relies on glucose for energy. When brain cells become resistant to insulin, it can impair cognitive function, leading to the “brain fog” many individuals report. There is a strong association between insulin resistance in mid-life and an increased risk for developing neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

Chronically elevated insulin levels directly promote vascular inflammation and unfavorable lipid profiles, establishing a direct link between metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.

Organ Response to Insulin Signaling

The following table illustrates how different key tissues respond to insulin signals in a healthy versus an insulin-resistant state, demonstrating the systemic nature of the condition.

| Organ / Tissue | Healthy Insulin Response | Insulin-Resistant Response |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle |

Efficient glucose uptake via GLUT4 for energy use and glycogen storage. |

Reduced glucose uptake, leading to higher blood sugar and less available energy for muscle function. |

| Liver |

Suppresses glucose production (gluconeogenesis). Promotes glycogen storage. |

Continues to produce and release glucose into the blood. Increases fat production (de novo lipogenesis), leading to NAFLD. |

| Adipose (Fat) Tissue |

Promotes glucose uptake and fat storage. Suppresses the breakdown of fats (lipolysis). |

Becomes resistant to insulin’s anti-lipolytic effect, releasing fatty acids into the bloodstream, which worsens insulin resistance in other tissues. |

| Ovaries (Female) |

Normal regulation of hormone production. |

Hyperinsulinemia stimulates excess androgen (testosterone) production, contributing to PCOS. |

| Pancreas |

Produces appropriate amounts of insulin in response to meals. |

Works overtime to produce excessive amounts of insulin (hyperinsulinemia), eventually leading to beta-cell exhaustion and failure. |

Academic

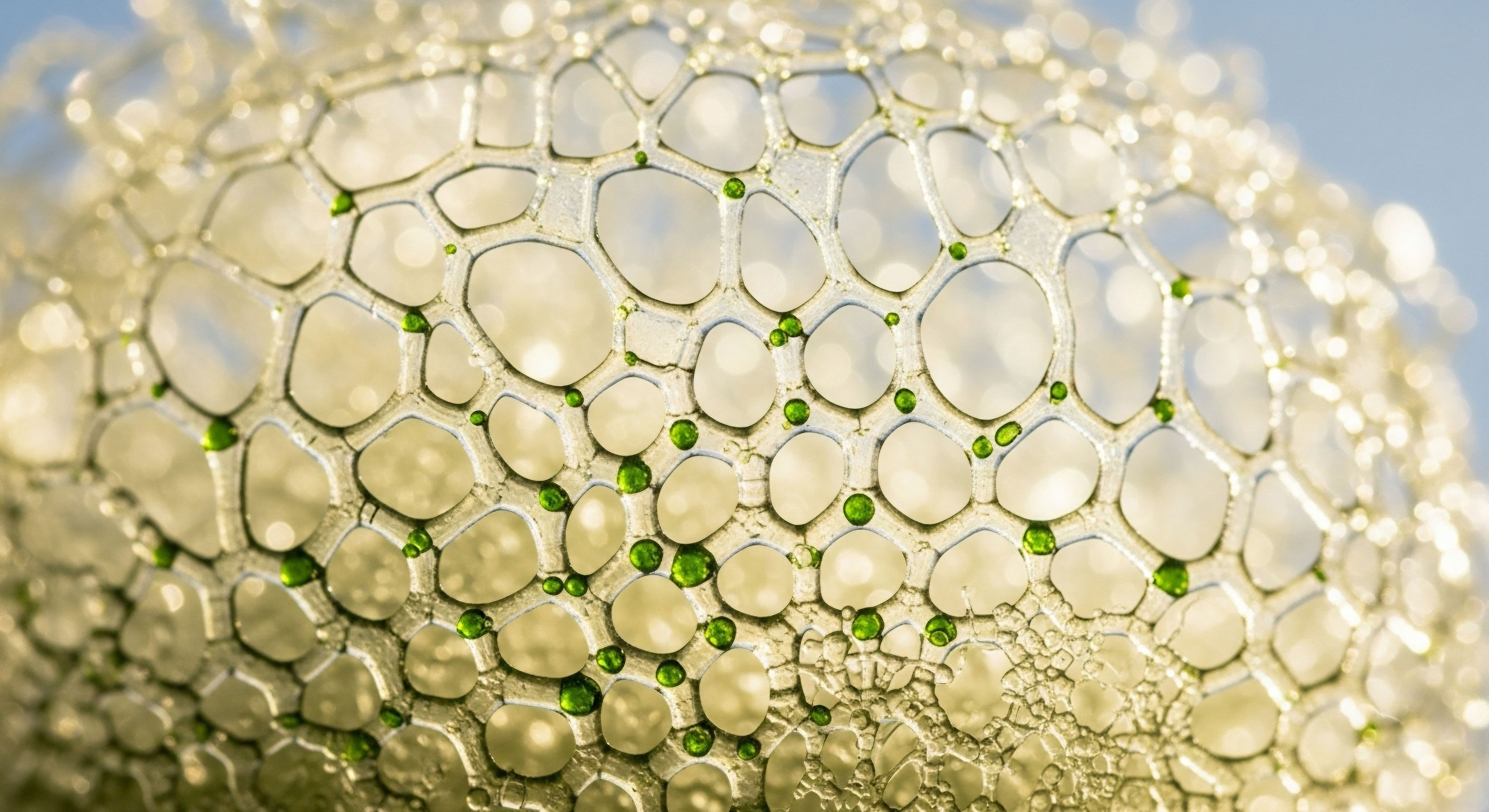

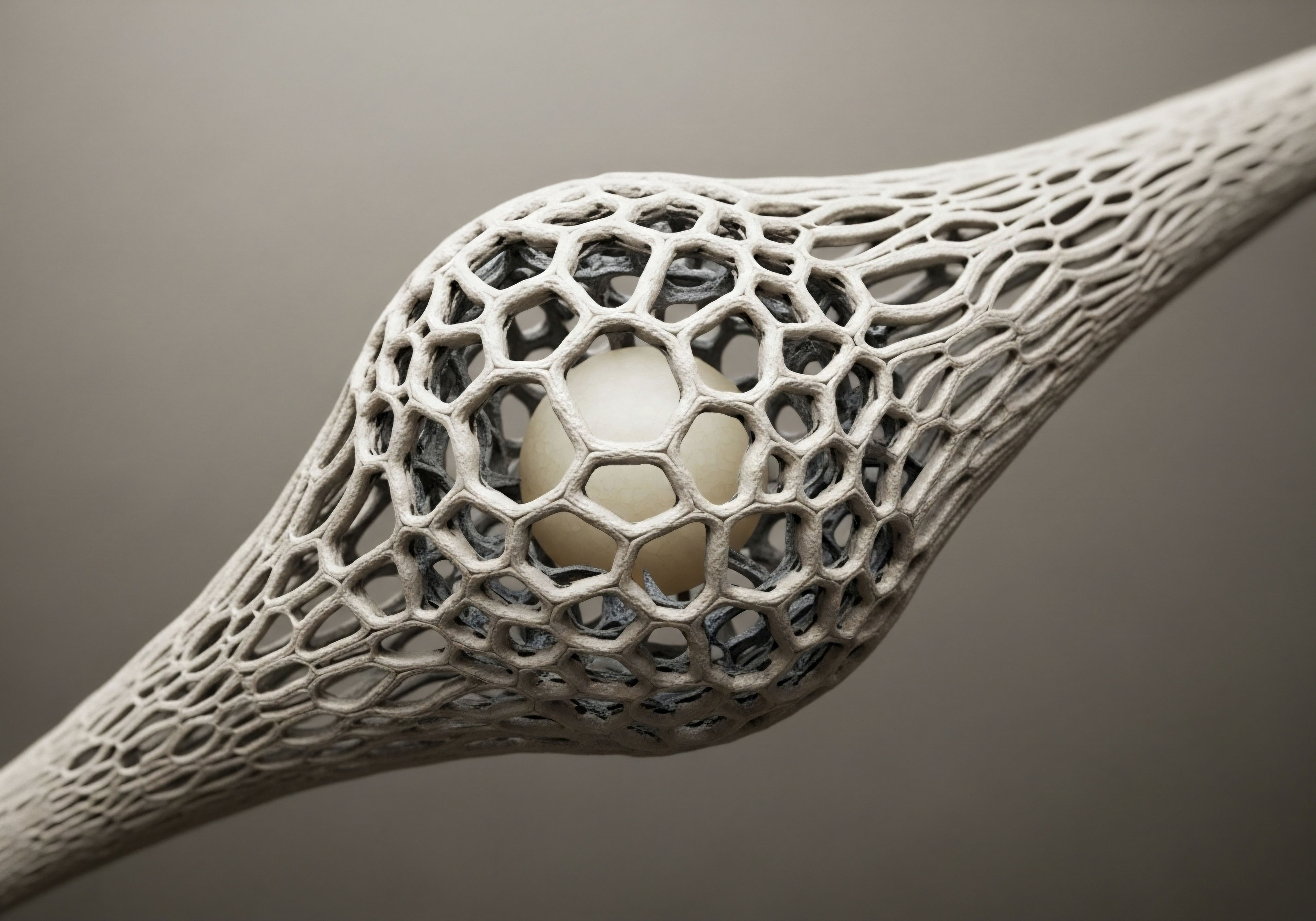

At the most fundamental level, the long-term consequences of impaired insulin receptor sensitivity are the result of a progressive failure in a biological process known as receptor trafficking. The insulin receptor (INSR) is not a static fixture on the cell surface. It is a dynamic entity, continuously cycling between the plasma membrane and the cell’s interior.

This process of internalization, or endocytosis, is critical for attenuating the insulin signal and maintaining cellular responsiveness. When this trafficking is disturbed, the entire system enters a self-perpetuating cycle of dysfunction that drives the pathology of metabolic disease.

The Vicious Cycle of INSR Downregulation

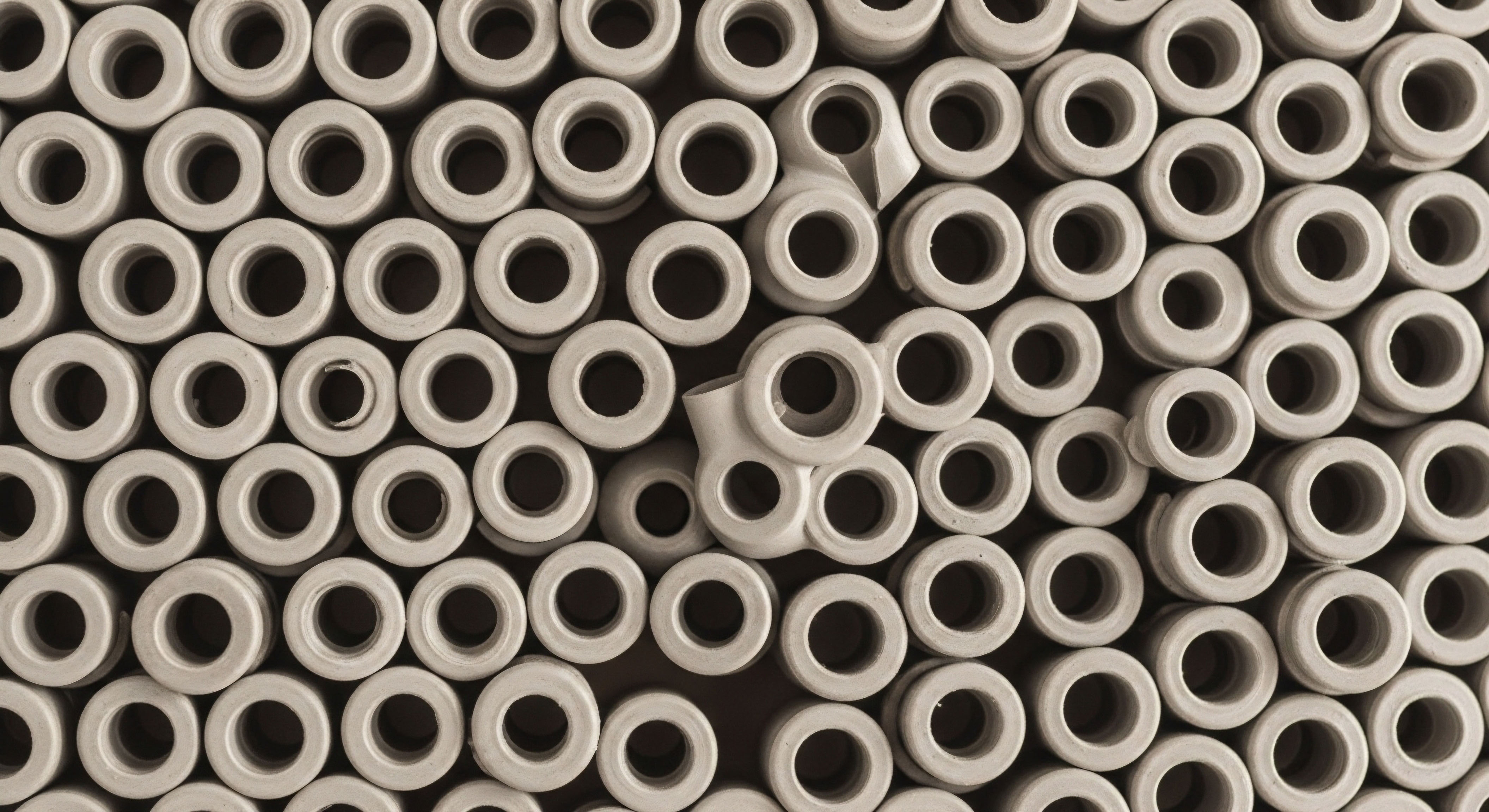

In a state of chronic hyperinsulinemia, the cell is bombarded with an overwhelming insulin signal. As a protective measure against overstimulation, the cell accelerates the internalization and subsequent degradation of the insulin-insulin receptor complex. The normal recycling process, where the INSR is stripped of its ligand (insulin) in the early endosome and returned to the cell surface, becomes impaired.

A larger proportion of internalized receptors are shunted toward the lysosome for degradation instead of being recycled. This leads to a net reduction in the number of available insulin receptors on the plasma membrane.

With fewer receptors available, the cell becomes even less sensitive to insulin, which in turn signals the pancreas to release more, creating a positive feedback loop that deepens the insulin-resistant state. This downregulation of INSR is a key molecular event in the transition from simple insulin resistance to overt type 2 diabetes.

What Cellular Factors Exacerbate Receptor Dysfunction?

The function of the INSR is also highly dependent on its environment ∞ the lipid composition and fluidity of the plasma membrane. Alterations in the membrane’s lipid profile can directly impair receptor function. For instance, an accumulation of specific gangliosides, such as GM3, within the membrane has been shown to disrupt the INSR’s ability to signal effectively.

Similarly, changes in cholesterol content can affect the integrity of caveolae, specialized lipid raft domains where a portion of INSR signaling occurs. Disruption of these domains is linked to the development of insulin resistance. Systemic inflammation, a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, contributes to this dysfunction by releasing cytokines that can interfere with the insulin signaling cascade at multiple post-receptor steps, further compounding the primary defect in receptor sensitivity.

The degradation of insulin receptors, a cellular defense against the stress of high insulin levels, paradoxically deepens the state of insulin resistance over time.

Molecular Interventions and Hormonal Recalibration

Understanding these deep cellular mechanisms opens avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions that go beyond conventional glucose management. The goal becomes restoring cellular sensitivity and breaking the cycle of hyperinsulinemia and receptor downregulation.

Targeted Peptide Therapies

Growth hormone peptides, such as the combination of Ipamorelin and CJC-1295, represent a sophisticated approach. These peptides stimulate the body’s natural production of growth hormone, which has potent effects on body composition. By promoting an increase in lean muscle mass and a decrease in adiposity (particularly visceral fat), they improve the body’s overall metabolic environment.

Muscle is the primary site of insulin-mediated glucose disposal, so increasing muscle mass enhances the body’s capacity for glucose uptake. Reducing visceral fat decreases the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and adipokines that promote insulin resistance. These peptides work to restore a more favorable cellular environment for insulin signaling.

Hormone Optimization Protocols

Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) in men with clinically low testosterone is another direct intervention. Testosterone has a direct, positive effect on insulin sensitivity. It promotes the growth of skeletal muscle and appears to enhance GLUT4 expression and translocation, directly countering the primary defect in insulin-resistant muscle cells.

By restoring testosterone to optimal physiological levels, TRT can be a powerful tool for improving glycemic control and breaking the metabolic cycle that links low testosterone and insulin resistance. For women, particularly in the peri- and post-menopausal phases, hormonal recalibration with low-dose testosterone and progesterone can similarly support metabolic health by preserving muscle mass and mitigating the central adiposity that often accompanies this life stage.

Stages of Insulin Receptor Pathway Disruption

The progression from a healthy state to severe insulin resistance can be mapped at the molecular level. The following table outlines this degenerative process.

| Stage | Receptor Status | Intracellular Signaling | Systemic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ∞ Initial Impairment |

Normal receptor number, but early signs of reduced binding affinity or environmental interference (e.g. inflammation). |

Slight blunting of the post-receptor signaling cascade (e.g. IRS-1/PI3K pathway). |

Compensatory hyperinsulinemia begins. Blood glucose remains normal. |

| 2 ∞ Receptor Downregulation |

Reduced number of INSR on the cell surface due to impaired recycling and accelerated degradation. |

Significantly attenuated signal transduction. Fewer GLUT4 transporters reach the cell membrane. |

Worsening hyperinsulinemia. Post-meal blood sugar begins to rise (impaired glucose tolerance). |

| 3 ∞ Severe Resistance |

Drastically reduced receptor density and severe signaling defects. |

Cellular machinery is highly resistant to insulin’s effects. Widespread signaling failure. |

Pancreatic beta-cell exhaustion. Overt Type 2 Diabetes with chronic hyperglycemia. |

| 4 ∞ Multi-System Failure |

Cellular dysfunction extends beyond metabolic control, affecting all insulin-sensitive tissues. |

Chronic cellular stress, inflammation, and glucotoxicity. |

Development of advanced complications ∞ neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, and severe cardiovascular disease. |

Key Steps in Disrupted INSR Trafficking

The breakdown of the insulin receptor pathway is a multi-step process. The following points detail the sequence of events at a cellular level:

- Ligand Binding and Internalization In a hyperinsulinemic state, the constant presence of insulin leads to persistent receptor occupation and internalization.

- Endosomal Sorting Failure Once inside the early endosome, the cellular machinery responsible for dissociating the insulin from its receptor and sorting the receptor for recycling becomes overwhelmed.

- Lysosomal Targeting A greater proportion of the internalized receptors are directed to the lysosome, the cell’s waste disposal system, for complete degradation.

- Reduced Membrane Return The rate of receptor degradation outpaces the rate of synthesis of new receptors, leading to a progressive depletion of INSR from the cell surface.

- Feedback Loop Reinforcement The resulting decrease in cell surface receptors makes the cell even more resistant to insulin, signaling the pancreas for higher output and perpetuating the entire cycle.

References

- Tan, S. & Li, Z. (2019). Insulin Receptor Trafficking ∞ Consequences for Insulin Sensitivity and Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2019, 8476847.

- Al-Badrani, S. & Al-Sowayan, N. (2022). Consequences of Insulin Resistance Long Term in the Body and Its Association with the Development of Chronic Diseases. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines, 10, 96-109.

- Papatheodorou, K. Papanas, N. Banach, M. Papazoglou, D. & Edmonds, M. (2016). Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2016, 8915750.

- Wilcox, G. (2005). Insulin and Insulin Resistance. Clinical Biochemist Reviews, 26(2), 19 ∞ 39.

- Garvey, W. T. Olefsky, J. M. & Marshall, S. (1987). Long-term effect of insulin on glucose transport and insulin binding in cultured adipocytes from normal and obese humans with and without non-insulin-dependent diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 80(4), 1143 ∞ 1152.

Reflection

From Knowledge to Personal Protocol

You now possess a detailed map of the biological terrain, from the initial whisper of cellular miscommunication to the systemic cascade of chronic disease. You can trace the path from a feeling of persistent fatigue to the molecular process of insulin receptor downregulation. This knowledge is a powerful diagnostic tool.

It transforms abstract symptoms into concrete, understandable physiological events. The critical next step is to overlay this map onto your own unique biology. Where do your personal experiences, your symptoms, and your lab results fall on this continuum? Understanding the mechanism is the foundation. Applying that understanding to your own life, through targeted diagnostics and personalized protocols, is how you begin to reclaim function and vitality. This journey from comprehension to action is the essence of proactive wellness.

Glossary

impaired insulin receptor sensitivity

insulin receptor

insulin receptor sensitivity

hyperinsulinemia

blood glucose

metabolic health

insulin resistance

receptor sensitivity

metabolic syndrome

blood sugar

impaired insulin receptor

signaling cascade

high insulin levels

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

de novo lipogenesis

polycystic ovary syndrome

insulin levels directly promote

that often accompanies this

atherogenic dyslipidemia

glucose uptake

insulin signaling

growth hormone peptides