Fundamentals

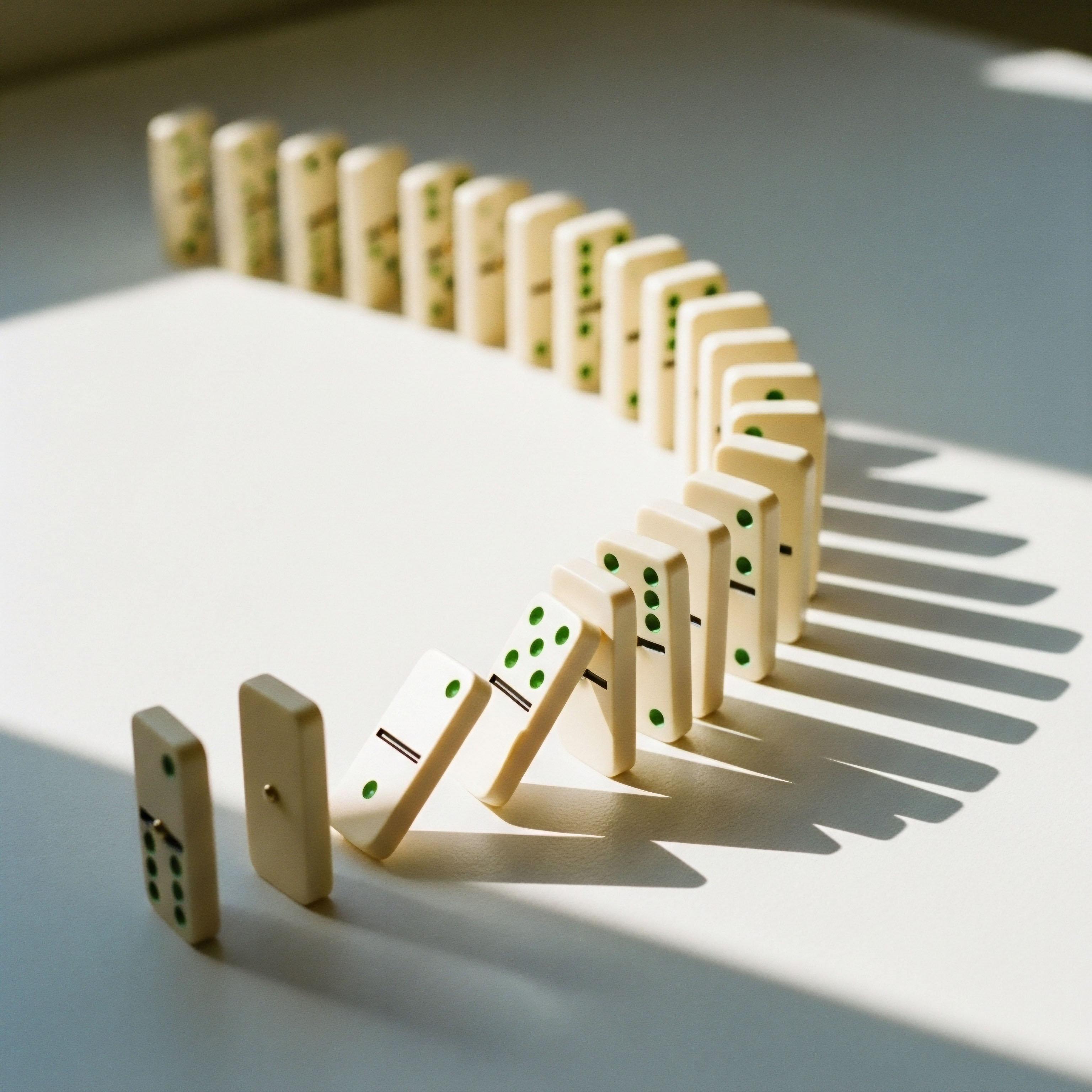

Your body operates as an intricate, interconnected system, a biological orchestra where hormones act as the conductors, guiding everything from your energy levels to your emotional state. When a specific hormonal pathway is intentionally altered, as it is with Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy, the effects ripple through this entire system.

You may be considering or currently undergoing this therapy for a variety of reasons, from managing endometriosis or prostate cancer to addressing precocious puberty. It is entirely natural to question how such a fundamental biological shift might affect your cognitive function ∞ your ability to think, remember, and plan. This is a valid and important concern, one that touches upon the very core of your sense of self.

At its heart, GnRH agonist therapy works by modulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the primary communication highway between your brain and your reproductive organs. GnRH is the initial messenger, produced in the hypothalamus, that travels to the pituitary gland, instructing it to release other key hormones ∞ luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

These hormones, in turn, signal the gonads (testes or ovaries) to produce testosterone or estrogen. GnRH agonists introduce a continuous, high-level signal that initially stimulates but then profoundly desensitizes the pituitary’s receptors. The result is a significant reduction in the production of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen, creating a state of temporary, reversible hormonal suppression.

Understanding the long-term cognitive outcomes of GnRH agonist therapy requires looking at how the brain functions when key hormonal messengers are intentionally quieted.

The brain itself is a hormone-responsive organ. Steroid hormones such as estrogen and testosterone play a direct role in maintaining healthy brain function. Receptors for these hormones are found in critical brain regions like the hippocampus, which is central to memory formation, and the cerebral cortex, responsible for executive functions like planning and problem-solving.

When the levels of these hormones are significantly lowered through GnRH agonist therapy, the brain’s internal environment changes. This biochemical shift is the primary mechanism through which cognitive effects, both short-term and potentially long-term, can occur. The experience is unique to each individual, shaped by their underlying health, the duration of the therapy, and their own biological predispositions.

The Brains Hormonal Environment

Your cognitive world, the seamless way you recall a memory, learn a new skill, or focus on a complex task, is deeply influenced by the biochemical milieu of your brain. Estrogen and testosterone are not just reproductive hormones; they are powerful neuromodulators.

They support the growth and survival of neurons, promote synaptic plasticity (the ability of brain connections to strengthen or weaken over time), and influence the production of neurotransmitters. For instance, estrogen has been shown to have a protective effect on the brain, potentially shielding it from age-related decline and certain neurodegenerative processes. Testosterone similarly contributes to cognitive vitality, with its decline in aging men often linked to changes in memory and spatial reasoning.

When GnRH agonist therapy is initiated, it creates a state of induced hypogonadism, mimicking the hormonal environment of menopause or andropause. This sharp decline in circulating sex hormones can lead to a range of symptoms. While physical symptoms like hot flashes or reduced libido are widely recognized, the cognitive and emotional effects are just as real and deserve equal attention.

Patients may report a sense of “brain fog,” a subtle but persistent difficulty with word retrieval, or a noticeable change in their ability to multitask. These experiences are a direct reflection of the brain adapting to a new hormonal state. The key question then becomes ∞ what happens to these cognitive functions once the therapy is completed and the HPG axis is allowed to resume its natural rhythm?

How Does GnRH Itself Affect the Brain?

Beyond its role in the HPG axis, GnRH itself appears to have direct effects on the brain. Research has identified GnRH receptors in areas outside the pituitary, including the hippocampus and other structures within the limbic system, which is the emotional center of the brain.

This suggests that GnRH may be involved in more than just reproductive timing; it could play a role in modulating cognitive processes and emotional regulation directly. Animal studies have explored this connection, with some research indicating that blocking GnRH receptors can lead to subtle changes in spatial memory and emotional control.

This adds another layer of complexity to understanding the full spectrum of cognitive outcomes. The therapy’s impact is a result of both the downstream reduction in sex hormones and the direct action of modulating GnRH signaling within the brain itself.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of hormonal influence on the brain, we can examine the specific clinical protocols and the mechanistic pathways through which GnRH agonist therapy exerts its effects. The decision to initiate this therapy is always based on a careful weighing of benefits and risks, and a deeper appreciation of the underlying science can empower you to have more informed conversations with your clinical team.

The primary therapeutic goal of GnRH agonist therapy is to induce a state of profound gonadal suppression, which is achieved by altering the normal pulsatile release of GnRH that the pituitary gland is accustomed to seeing.

The pituitary gland is designed to respond to rhythmic, pulsatile signals from the hypothalamus. A GnRH agonist, however, provides a constant, high-amplitude signal. Initially, this leads to a “flare” effect, a temporary surge in LH, FSH, and consequently, testosterone or estrogen.

Within a few weeks, this unrelenting stimulation leads to the downregulation and desensitization of GnRH receptors on the pituitary’s gonadotrope cells. The cells essentially become unresponsive, leading to a dramatic drop in LH and FSH secretion. This effectively shuts down the primary signal for the testes or ovaries to produce sex hormones, achieving the desired therapeutic state of hypogonadism. The cognitive effects experienced during this period are a direct consequence of the brain adapting to this low-steroid environment.

Clinical Applications and Cognitive Considerations

The specific context in which GnRH agonist therapy is used can influence the cognitive outcomes observed. The duration of treatment, the patient’s age, and the underlying condition all play a role. For instance, in the treatment of prostate cancer, GnRH agonists are a cornerstone of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Given that this therapy can continue for years, there is a growing body of research focused on its long-term cognitive impact. Some studies have found that men undergoing ADT may be more likely to experience impairments in cognitive domains such as memory, processing speed, and executive function compared to control groups. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring cognitive health throughout the treatment journey.

In pediatric populations, such as in the treatment of central precocious puberty, the considerations are different. Here, the therapy is used to temporarily pause pubertal development, with the goal of preserving adult height potential. Research in this area has sought to determine if this temporary suppression has any lasting effects on cognitive development once the therapy is discontinued and puberty resumes.

One study found that while there were no long-term negative effects on overall IQ or psychosocial functioning in young adults who had received GnRH agonist therapy in addition to growth hormone, the treated group did report a lower self-perception of their own cognitive functioning. This highlights a potential disconnect between objective cognitive performance and subjective experience.

The brain’s adaptation to a low-hormone state is a complex process, with different cognitive domains potentially being affected in unique ways.

Investigating Brain Connectivity and Function

To understand the biological basis for these cognitive changes, researchers have begun to use advanced neuroimaging techniques to look at how GnRH agonist therapy affects brain structure and function. One study using functional MRI (fMRI) in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty investigated interhemispheric functional connectivity ∞ how well different regions in the two halves of the brain communicate with each other.

The study found that long-term treatment with a GnRH agonist was associated with increased connectivity in brain areas responsible for memory and visual processing. This suggests that the brain may undergo adaptive changes to compensate for the altered hormonal environment. The researchers also noted a correlation between these connectivity changes and the levels of luteinizing hormone, further cementing the link between the hormonal changes and brain function.

Animal models have provided additional insights into the structural and molecular changes that may occur. In a study using a sheep model, peri-pubertal treatment with a GnRH agonist was found to result in larger amygdala volumes, particularly in females. The amygdala is a key component of the limbic system, involved in processing emotions like fear and anxiety.

The same study also found that the treatment was associated with sex- and hemisphere-specific changes in the expression of genes related to synaptic plasticity. While these findings from animal models cannot be directly extrapolated to humans, they provide valuable clues about the potential biological mechanisms underlying the cognitive and emotional effects of GnRH agonist therapy. They suggest that the therapy can induce lasting changes in brain structure and gene expression, which could plausibly have long-term functional consequences.

The table below summarizes the key differences in the application and cognitive considerations of GnRH agonist therapy in different patient populations.

| Patient Population | Primary Therapeutic Goal | Key Cognitive Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Adults with Prostate Cancer | Androgen Deprivation (suppression of testosterone) | Potential for long-term impairment in memory, processing speed, and executive function. |

| Adults with Endometriosis | Estrogen Suppression | Reports of “brain fog,” mood disturbances, and memory complaints, often similar to menopausal symptoms. |

| Children with Precocious Puberty | Temporary delay of pubertal development | Generally no long-term impact on IQ, but potential for lower self-perception of cognitive abilities. |

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the long-term cognitive sequelae of GnRH agonist therapy requires a systems-biology perspective, integrating insights from endocrinology, neuroscience, and molecular biology. The primary mechanism of action, pituitary desensitization, is well-established.

The more complex question lies in the secondary and tertiary effects of profound hypogonadism on a nervous system that is both structurally and functionally dependent on the trophic support of sex steroids. The existing body of research, while still evolving, points towards a complex interplay of factors, including direct GnRH signaling in extra-pituitary sites, alterations in neuroplasticity, and potential epigenetic modifications.

The cognitive domains most frequently implicated in studies of GnRH agonist therapy are those subserved by the prefrontal cortex and the medial temporal lobe, namely executive function and declarative memory. This is biologically plausible, given the high density of androgen and estrogen receptors in these brain regions.

These steroid hormones are not passive occupants of the neural landscape; they actively regulate synaptic architecture, dendritic spine density, and long-term potentiation (LTP), the cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory. Therefore, the abrupt withdrawal of these neuroprotective and neurotrophic factors creates a biological challenge to which the brain must adapt. The long-term cognitive outcome likely depends on the resilience of these neural circuits and the brain’s capacity for compensatory reorganization.

What Are the Molecular Mechanisms at Play?

Delving into the molecular level, we can postulate several mechanisms through which GnRH agonist-induced hypogonadism could lead to lasting cognitive changes. One avenue of investigation is the impact on neuroinflammation. Estrogen, for example, is known to have anti-inflammatory properties within the central nervous system.

Its prolonged absence could lead to a more pro-inflammatory state, which has been linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative processes. Another potential mechanism involves the modulation of key neurotransmitter systems. Both estrogen and testosterone influence the synthesis and activity of acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin, all of which are critical for attention, mood, and memory. A sustained alteration in the hormonal milieu could thus lead to a persistent dysregulation of these neurotransmitter systems.

Furthermore, the direct action of GnRH on extra-pituitary receptors presents an intriguing area of research. Animal studies have shown that GnRH signaling can influence the expression of genes involved in synaptic plasticity and cell survival. A study on sheep demonstrated that peri-pubertal GnRH agonist treatment led to sex- and hemisphere-specific changes in the mRNA expression of genes in the hippocampus.

This suggests that the therapy might induce lasting, potentially epigenetic, changes in how these genes are regulated. Such changes could plausibly alter the trajectory of brain development and aging, with cognitive consequences that may only become apparent years after the treatment has ceased. The challenge for future research is to elucidate these complex molecular pathways in human subjects.

The brain’s response to hormonal suppression is not a passive process but an active adaptation involving structural, functional, and molecular changes.

Longitudinal Studies and Future Directions

To definitively characterize the long-term cognitive outcomes of GnRH agonist therapy, large-scale, prospective longitudinal studies are needed. Such studies would need to follow patients from baseline, through treatment, and for many years post-treatment, using a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests and advanced neuroimaging techniques.

One of the key methodological challenges in the current literature is the heterogeneity of study designs, patient populations, and cognitive assessment tools. Standardizing these elements would allow for more robust and generalizable conclusions.

For example, a study of prostate cancer patients on ADT found that while mean cognitive performance did not differ from control groups over 12 months, the ADT group was twice as likely to exhibit clinically significant cognitive impairment on at least two tests. This type of analysis, focusing on individual-level change, is crucial for identifying those most at risk.

Future research should also explore potential interventions to mitigate any negative cognitive effects. Could lifestyle interventions, such as physical exercise or cognitive training, bolster cognitive reserve in patients undergoing GnRH agonist therapy? Are there specific pharmacological agents that could protect the brain from the effects of steroid hormone withdrawal?

Answering these questions will be paramount for optimizing the clinical use of this important class of drugs. The goal is to maximize the therapeutic benefits of GnRH agonist therapy while minimizing its potential impact on cognitive health and quality of life. A deeper understanding of the underlying neurobiology is the first and most critical step in achieving this goal.

The following table outlines some of the key research findings from both human and animal studies, highlighting the specific cognitive domains and biological changes observed.

| Study Type | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Human (Precocious Puberty) | No long-term effects on IQ, but lower self-perception of cognitive function. | Suggests a potential disconnect between objective performance and subjective experience. |

| Human (Prostate Cancer) | Increased risk of impairment in memory, processing speed, and executive functions. | Highlights the need for cognitive monitoring in long-term ADT. |

| Human (fMRI Study) | Increased interhemispheric connectivity in memory and visual processing areas. | Indicates potential compensatory brain reorganization during therapy. |

| Animal (Sheep Model) | Increased amygdala volume and altered gene expression related to synaptic plasticity. | Provides clues to the structural and molecular mechanisms of cognitive effects. |

- Neurotrophic Support ∞ Sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone promote the health and survival of neurons. Their withdrawal can challenge the brain’s structural integrity.

- Synaptic Plasticity ∞ The ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken, which is the basis of learning, is influenced by hormonal signals. GnRH agonist therapy can alter this delicate balance.

- Neurotransmitter Regulation ∞ Hormonal changes can impact the function of key neurotransmitter systems, affecting mood, attention, and memory.

- Cognitive Reserve ∞ An individual’s baseline cognitive capacity and brain health can influence their resilience to the effects of hormonal suppression.

References

- Mul, D. et al. “Cognition, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Psychosocial Functioning After GH/GnRHa Treatment in Young Adults Born SGA.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 105, no. 3, 2020, pp. e387-e396.

- Wang, C. et al. “Influence of Gonadotropin Hormone Releasing Hormone Agonists on Interhemispheric Functional Connectivity in Girls With Idiopathic Central Precocious Puberty.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 11, 2020, p. 34.

- Nuruddin, S. et al. “Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on brain development and aging ∞ results from two animal models.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 38, no. 12, 2013, pp. 2981-91.

- Perkins, S. M. et al. “Cognitive Impairment Following Hormone Therapy ∞ Current Opinion of Research in Breast and Prostate Cancer Patients.” Current Treatment Options in Oncology, vol. 19, no. 10, 2018, p. 51.

- Haraldsen, I. R. et al. “Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist on brain development and aging ∞ results from two animal models.” Brage NMBU, 2013.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a window into the complex relationship between your endocrine system and your cognitive health. It is a starting point, a framework for understanding the biological reasons behind the experiences you may be having. Your personal health narrative is unique, written in the language of your own biology and lived experiences.

The data and clinical observations provide the grammar and vocabulary, but you are the author of your story. As you move forward, consider how this knowledge can transform your relationship with your own health.

It is an invitation to become a more active, informed participant in your wellness journey, to ask deeper questions, and to seek a path that honors the intricate and intelligent system that is your body. The ultimate goal is to move from a place of concern to a position of empowered self-stewardship.

Glossary

precocious puberty

prostate cancer

gnrh agonist therapy

hormonal suppression

sex hormones

cognitive effects

gnrh agonist

synaptic plasticity

hormonal environment

cognitive outcomes

which gnrh agonist therapy

androgen deprivation therapy

executive function

cognitive domains

central precocious puberty

potential disconnect between objective

girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty

gnrh agonist therapy requires

neuroplasticity

declarative memory

long-term cognitive outcomes