Fundamentals

The sensation of a subtle shift in your cognitive clarity, that feeling of mental fog or a name that is suddenly just out of reach, is a deeply personal and often unsettling experience. Your lived reality of these moments is the starting point of a vital health investigation.

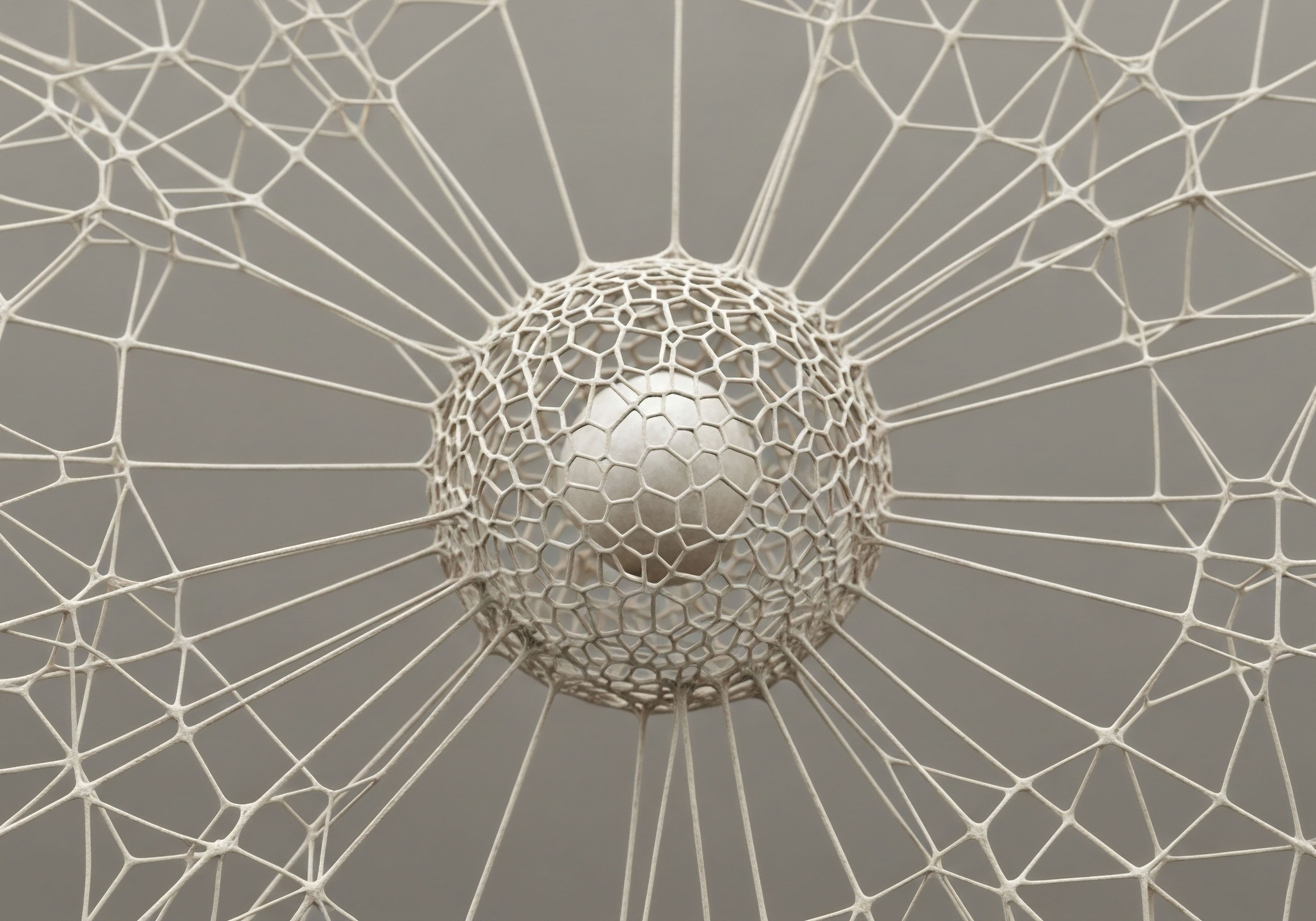

These are not failures of intellect; they are signals from your body’s intricate internal communication network, the endocrine system. This system orchestrates your biology through chemical messengers called hormones. Among the most powerful of these messengers is estrogen, a molecule that does far more than regulate reproductive cycles. It is a fundamental conductor of brain health, influencing everything from energy metabolism in your neurons to the very structure of the connections between them.

Understanding the connection between your hormones and your cognitive function begins with appreciating the brain’s profound sensitivity to its chemical environment. Estrogen receptors are found throughout the brain, in regions critical for memory, mood, and higher-level thinking. When estrogen levels are optimal and stable, the hormone acts as a guardian for neural circuits.

It supports the flexibility and growth of synapses, the communication points between brain cells. It also promotes healthy blood flow, ensuring your brain receives the oxygen and glucose it needs to function effectively. The transition into menopause, particularly when it occurs earlier in life, represents a significant disruption to this previously stable neurochemical architecture. The decline in estrogen production can leave the brain vulnerable, leading to the very real symptoms of cognitive change that you may be experiencing.

The subjective experience of cognitive fog during menopause is a direct reflection of objective changes in the brain’s hormonal environment.

This biological reality forms the basis of our entire discussion. The question of intervening with hormonal therapies is a question of how, when, and if we can support the brain as it adapts to this new biochemical state. The science has evolved considerably, moving from a one-size-fits-all model to a highly personalized and time-sensitive understanding.

The conversation about hormonal support is about restoring a specific biological function and recalibrating a system that is in flux. It is a proactive step in your personal health journey, grounded in the principle that understanding your own biological systems is the key to reclaiming vitality and function.

Intermediate

The clinical science surrounding menopausal hormone therapy and cognition is defined by a central concept known as the “critical window” or “timing hypothesis.” This principle posits that the brain’s response to estrogen therapy is profoundly dependent on when it is initiated relative to the final menstrual period. The biological state of the brain in early menopause is distinctly different from its state a decade or more later. This distinction is the primary determinant of the therapy’s long-term cognitive outcomes.

The Tale of Two Timelines

To grasp this concept, we can examine the results of two major sets of clinical investigations. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), which produced considerable concern, involved women who were, on average, 65 years or older when they began hormonal protocols. In this older population, the introduction of certain types of hormone therapy was associated with a decline in cognitive function. This outcome led to years of caution and uncertainty.

Subsequent research, however, painted a much clearer picture by focusing on a different population. The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) and the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of Younger Women (WHIMSY) specifically enrolled women who were in early menopause, typically within three to five years of their last period.

These studies were designed to test the timing hypothesis directly. The long-term follow-up of these participants, nearly a decade after the trials ended, provides our most robust data on the subject.

Initiating hormone therapy in early menopause shows no long-term negative or positive impact on cognitive function.

The results from the KEEPS Continuation Study are unambiguous ∞ women who received either oral conjugated equine estrogens or transdermal estradiol for four years during early menopause showed no difference in their cognitive performance ten years later compared to women who received a placebo. Their cognitive function was similar across multiple domains.

This finding is incredibly reassuring from a safety perspective. It tells us that for healthy women managing symptoms like hot flashes or sleep disruption, a course of hormone therapy started shortly after menopause does not appear to pose a long-term threat to cognitive health.

Comparing the Landmark Studies

The differences in study design and population are essential to understanding the divergent outcomes. The table below outlines the key distinctions that inform the timing hypothesis.

| Study Characteristic | WHIMS (Older Cohort) | KEEPS / WHIMSY (Younger Cohort) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Initiation | 65 years and older | Recently postmenopausal (within 6 years) |

| Time Since Menopause | Many years post-menopause | Early postmenopause (typically <3-5 years) |

| Primary Cognitive Finding | Increased risk of cognitive decline with therapy | No long-term benefit or harm from therapy |

| Key Implication | Hormone therapy initiated late may be detrimental. | Hormone therapy initiated early appears cognitively safe. |

This data reframes the conversation. The goal of hormonal optimization protocols in early menopause is primarily the alleviation of vasomotor and other systemic symptoms. The cognitive data provides powerful reassurance about the safety of this approach, while also clarifying that these protocols should not be viewed as a method for preventing future cognitive decline. The strongest predictor of cognitive performance later in life, according to the KEEPS Continuation study, was a woman’s cognitive function at the start of the study.

- Oral Conjugated Equine Estrogens (oCEE) ∞ This form of estrogen was used in both WHIMS and KEEPS. The KEEPS follow-up showed no long-term cognitive harm from its use in the early postmenopausal window.

- Transdermal Estradiol (tE2) ∞ This form, delivered through the skin, was also studied in KEEPS. There was an initial hypothesis that it might confer unique benefits, but long-term follow-up found its cognitive impact to be neutral, same as oCEE and placebo.

- Micronized Progesterone ∞ Used in conjunction with estrogen in women with a uterus to protect the endometrium. Its specific long-term cognitive impact is less studied in isolation but was part of the safe protocols in KEEPS.

Academic

From a systems-biology perspective, the brain’s response to exogenous estrogen is a matter of cellular health and receptor integrity. Estrogen’s neuroprotective actions are multifaceted, involving the modulation of neurotransmitter systems, the promotion of synaptogenesis, the regulation of cerebral blood flow, and anti-inflammatory effects.

The “critical window” hypothesis can be understood as the period during which the brain’s cellular machinery remains healthy enough and its estrogen receptors remain responsive enough to benefit from hormonal signaling. Once that window closes, the physiological landscape changes, and the introduction of estrogen may occur in a cellular environment that can no longer properly interpret its signals.

What Is the Neurobiological Basis of the Critical Window?

During perimenopause and early postmenopause, the decline in endogenous estrogen initiates a cascade of changes. However, the underlying neural architecture and its capacity for plasticity are largely preserved. Estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) are still present and functional. In this state, reintroduced estrogen can bind to these receptors and successfully promote downstream neuroprotective pathways.

It can support glucose transport into neurons, upregulate the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and suppress inflammatory cytokines. The KEEPS and WHIMSY trials operated within this window. Their neutral long-term findings suggest that a short-term course of therapy during this period is sufficient for symptom management and does not fundamentally alter the long-term trajectory of cognitive aging in either a positive or negative way once the therapy is stopped.

The long-term cognitive neutrality of early hormone therapy suggests the brain maintains homeostatic equilibrium after a temporary period of hormonal support.

Conversely, in late menopause, years of estrogen deprivation may lead to irreversible changes. Estrogen receptor expression and function may decline. The underlying vascular health of the brain may be compromised. In this altered state, the introduction of estrogen could have paradoxical effects.

A system that has adapted to a low-estrogen state may respond to a sudden influx of hormones in a non-physiological way, potentially promoting inflammation or other adverse cellular reactions. This provides a plausible biological mechanism for the detrimental cognitive findings observed in the older WHIMS cohort.

Cognitive Domains and Therapeutic Impact

The KEEPS Continuation Study was rigorous in its assessment, using a battery of tests to evaluate specific cognitive functions. The lack of effect was consistent across these different areas of cognition, strengthening the conclusion of neural safety and neutrality. The following table details the cognitive factors analyzed and the consistent findings.

| Cognitive Factor | Description of Abilities Measured | Long-Term Outcome in KEEPS Continuation |

|---|---|---|

| Verbal Learning & Memory | Acquiring and recalling verbal information. | No difference between therapy and placebo groups. |

| Auditory Attention & Working Memory | Focusing on auditory information and manipulating it in short-term memory. | No difference between therapy and placebo groups. |

| Visual Attention & Executive Function | Processing visual information and engaging in higher-order planning and problem-solving. | No difference between therapy and placebo groups. |

| Global Cognitive Score | An overall composite score representing general cognitive function. | No difference between therapy and placebo groups. |

How Does Cardiovascular Health Influence These Outcomes?

An important consideration is the health of the participants in these studies. The women in the KEEPS trial were selected for their low cardiovascular risk. This is a critical point. The health of the brain’s vascular system is inextricably linked to cognitive function.

Estrogen has known effects on blood vessels, and its impact may be very different in healthy, elastic arteries compared to vessels already burdened with atherosclerotic plaques. The reassuring safety findings from KEEPS may be most applicable to women with a similar low-risk cardiovascular profile. The negative outcomes in the older WHIMS cohort could be partly explained by the higher prevalence of subclinical vascular disease in that population, where estrogen’s effects might have been different.

What Are the Implications for Personalized Protocols?

The evidence directs us toward a highly personalized approach. A decision about hormone therapy requires a thorough evaluation of several factors:

- Timing ∞ The primary factor is proximity to the final menstrual period. The data strongly supports the safety of initiation within the early postmenopausal window.

- Symptoms ∞ The presence of moderate to severe menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes, night sweats, or sleep disturbances, is the principal indication for therapy.

- Cardiovascular Health ∞ A comprehensive assessment of cardiovascular risk is necessary to ensure the patient profile aligns with those studied in the trials that demonstrated safety.

The research provides a clear mandate. For the right person at the right time, menopausal hormone therapy is a valuable tool for symptom relief with a strong profile of long-term cognitive safety. It is also clear that it is not a therapy for cognitive enhancement or the prevention of age-related cognitive decline.

References

- Gleason, Carey E. et al. “Long-term cognitive effects of menopausal hormone therapy ∞ Findings from the KEEPS Continuation Study.” PLOS Medicine, vol. 21, no. 11, 2024, e1004505.

- Espeland, Mark A. et al. “Effect of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy on Cognitive Function in Younger Women ∞ The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of Younger Women.” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 173, no. 15, 2013, pp. 1424-1433.

- Resnick, Susan M. and Mark A. Espeland. “Estrogen, Cognition, and the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1179, 2009, pp. 62-75.

- Miller, Virginia M. et al. “The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) ∞ what have we learned?.” Menopause, vol. 26, no. 9, 2019, pp. 1071-1084.

- Shumaker, Sally A. et al. “Estrogen Plus Progestin and the Incidence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Postmenopausal Women ∞ The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study ∞ A Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA, vol. 289, no. 20, 2003, pp. 2651-2662.

Reflection

You now possess a clearer understanding of the intricate relationship between your hormonal landscape and your cognitive well-being. The data provides reassurance and clarifies the role of specific therapeutic interventions. This knowledge is the foundational tool for a more informed and empowered conversation about your health.

The journey of optimizing your well-being is a continuous one, built upon a partnership between your lived experience and objective clinical science. Consider what your personal health goals are. What does vitality mean to you? How does your cognitive function intersect with your daily life and future aspirations?

The answers to these questions, combined with the scientific evidence, will illuminate the most appropriate path forward for you, a path that is uniquely yours to define and follow in collaboration with your clinical guide.