Fundamentals

You may be noticing subtle shifts in your cognitive function. Words that were once readily available might now feel just out of reach. Perhaps you find yourself misplacing keys more often or struggling to maintain focus during complex tasks. These experiences are common, and they are valid data points.

They are your body’s method of communicating a change in its internal environment. Understanding the biological reasons for these shifts is the first step toward addressing them. One of the key players in this internal communication network is progesterone, a hormone that has a profound influence on brain health and function.

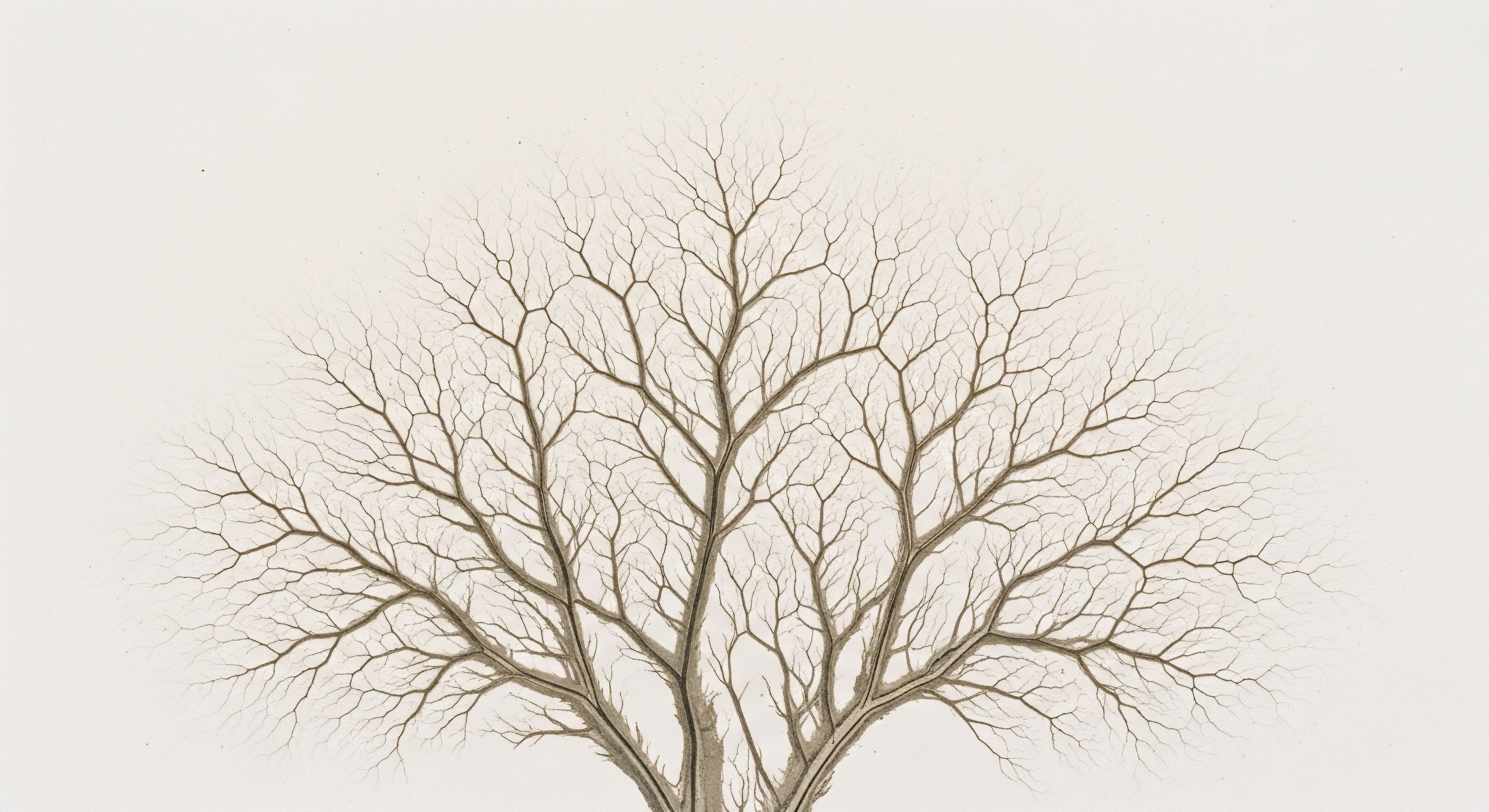

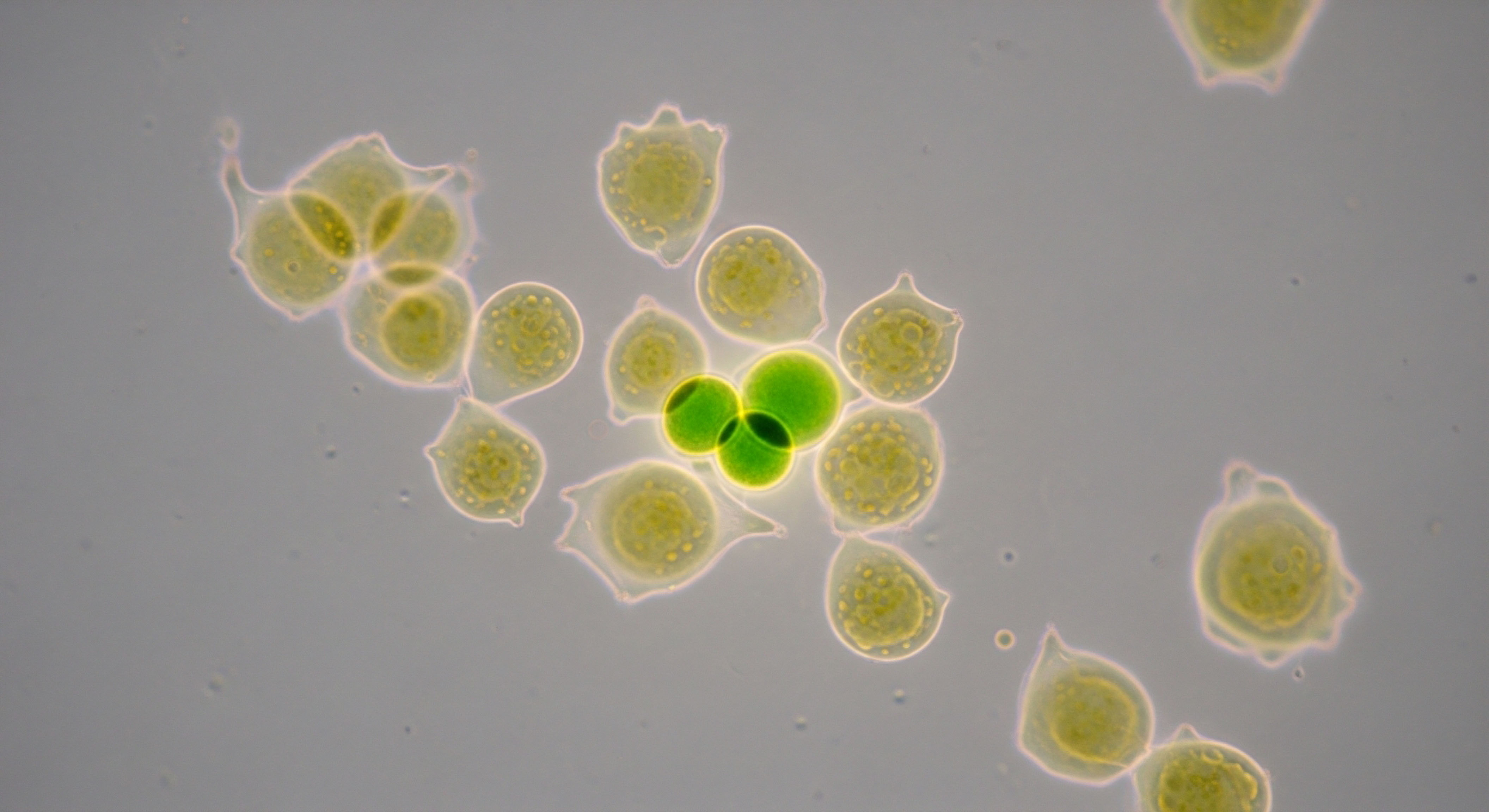

Progesterone is a steroid hormone produced primarily in the ovaries after ovulation, with smaller amounts made by the adrenal glands and, during pregnancy, the placenta. Its role extends far beyond the reproductive system. The brain is highly responsive to progesterone, containing numerous receptors for it in areas critical for memory, mood, and cognition, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

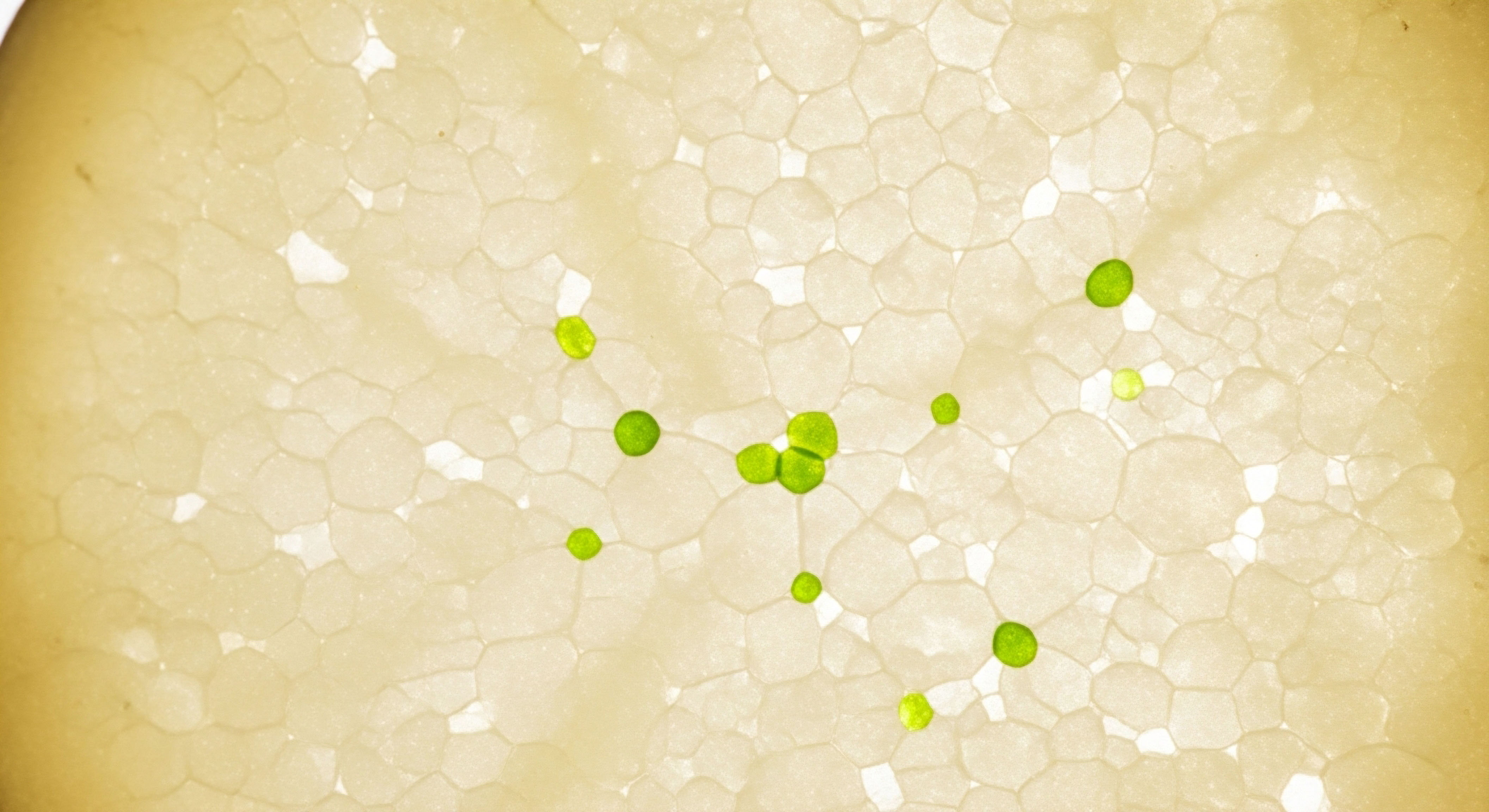

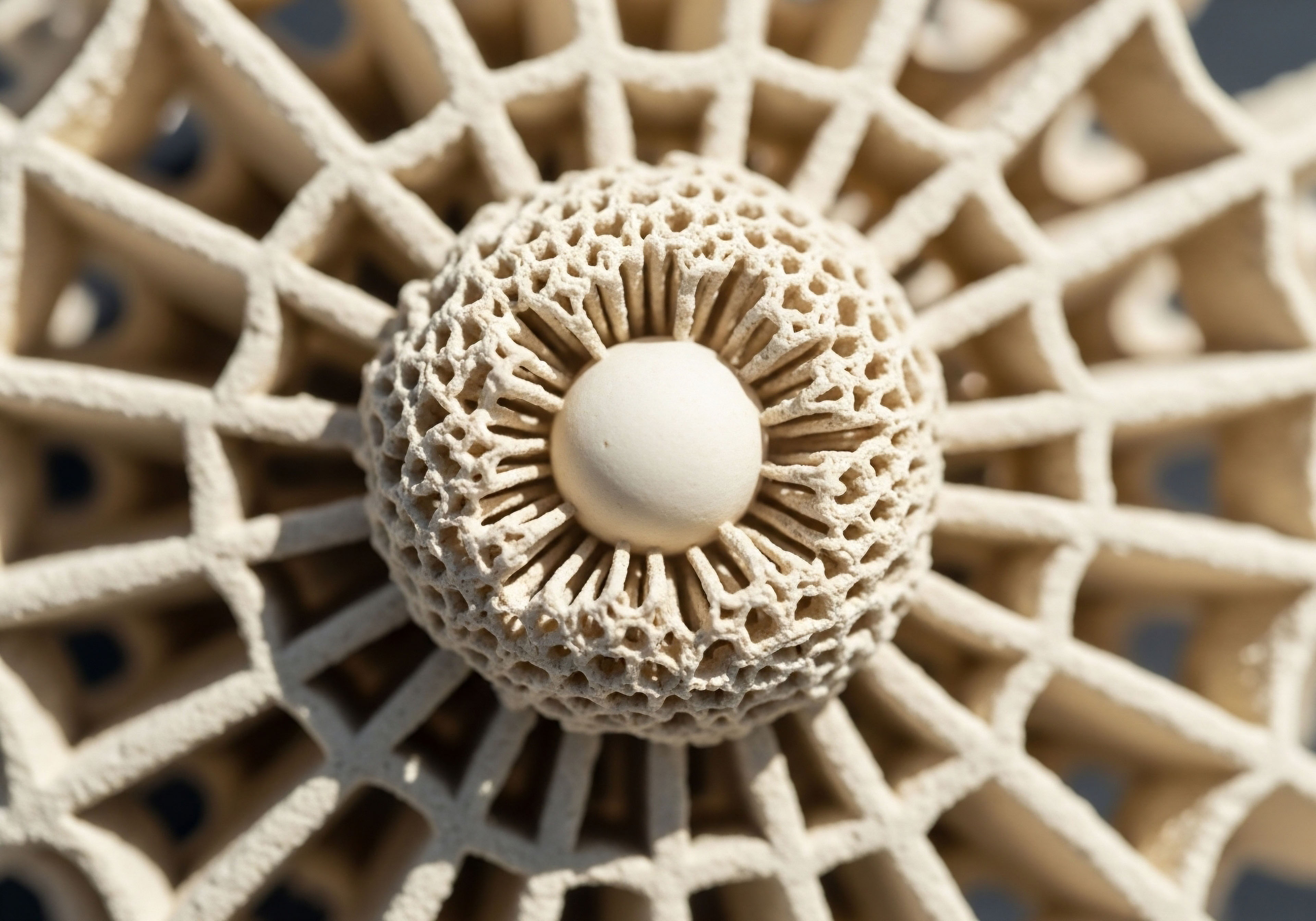

Progesterone’s influence on the brain is multifaceted. It promotes the formation of myelin, the protective sheath that insulates nerve fibers and ensures efficient communication between neurons. It also has a calming effect, interacting with GABA receptors in the brain, which helps to reduce anxiety and promote sleep. These actions are foundational to maintaining cognitive vitality.

Progesterone’s role in the brain is not limited to reproduction; it is a key modulator of neural health and cognitive processes.

As women transition through perimenopause and into menopause, progesterone levels decline significantly. This decline can contribute to many of the symptoms associated with this life stage, including hot flashes, sleep disturbances, and mood swings. The cognitive symptoms, such as brain fog and memory lapses, are also linked to this hormonal shift.

The reduction in progesterone can lead to a decrease in its neuroprotective effects, leaving the brain more vulnerable to inflammation and oxidative stress. Understanding this connection allows for a more targeted approach to supporting cognitive health during this transition. It provides a framework for understanding why replenishing this vital hormone may be a consideration for long-term cognitive well-being.

The conversation around hormonal health is evolving. It is moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach and toward a more personalized understanding of an individual’s unique biochemistry. Your symptoms are real, and they have a biological basis. By exploring the role of progesterone in cognitive function, you are taking an active role in your health journey.

This knowledge empowers you to ask informed questions and seek solutions that are tailored to your specific needs. The goal is to restore balance and function, allowing you to feel like yourself again.

Intermediate

When considering progesterone therapy for cognitive benefits, it is essential to understand the distinction between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins. Bioidentical progesterone is molecularly identical to the progesterone produced by the human body. This structural similarity allows it to bind effectively to progesterone receptors and exert its natural biological effects.

In contrast, synthetic progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), have a different molecular structure. While they can mimic some of progesterone’s effects on the uterine lining, they do not always interact with progesterone receptors in the brain in the same way. Some studies suggest that synthetic progestins may not offer the same neuroprotective benefits as natural progesterone and, in some cases, may even have negative cognitive effects.

How Does Progesterone Support Brain Health?

Progesterone’s influence on the brain is mediated through several key mechanisms. One of its most significant roles is in promoting neurogenesis, the formation of new neurons. It also supports synaptic plasticity, the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time, which is the basis of learning and memory.

Progesterone has been shown to reduce inflammation in the brain, a process that is increasingly linked to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, it has antioxidant properties, helping to protect brain cells from damage caused by free radicals. These actions collectively contribute to a healthier, more resilient brain.

The choice between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins is a critical consideration for those seeking cognitive benefits from hormone therapy.

The timing of hormone therapy initiation is another important factor. The “critical window” hypothesis suggests that hormone therapy is most effective and has the fewest risks when started in early menopause, typically within the first few years after the final menstrual period.

During this time, the brain’s hormonal receptors are still responsive, and the underlying neural architecture is relatively healthy. Initiating progesterone therapy during this window may help to preserve cognitive function and protect against age-related decline. However, starting hormone therapy later in life may not provide the same benefits and could potentially carry more risks. The KEEPS-Cog study, for instance, found no significant long-term cognitive benefits or harms from short-term hormone therapy initiated in recently postmenopausal women.

Clinical Protocols and Considerations

When progesterone therapy is prescribed for women, the dosage and delivery method are tailored to the individual’s needs and menopausal status. For postmenopausal women, progesterone is often prescribed in combination with estrogen to protect the uterine lining from the proliferative effects of unopposed estrogen. Common protocols include:

- Oral micronized progesterone ∞ This is a bioidentical form of progesterone that is well-absorbed and has been shown to have a calming, sleep-promoting effect. A typical dose is 100-200 mg taken at bedtime.

- Transdermal progesterone cream ∞ This is another bioidentical option that is applied to the skin. While it can be effective for some symptoms, its absorption can be variable, and it may not provide the same level of uterine protection as oral progesterone.

The following table provides a simplified comparison of bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins:

| Feature | Bioidentical Progesterone | Synthetic Progestins |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Identical to human progesterone | Different from human progesterone |

| Cognitive Effects | Generally positive or neutral | Inconsistent, potentially negative |

| Side Effects | Fewer side effects, often calming | Can include mood swings, bloating |

Academic

A deeper examination of progesterone’s role in cognitive function requires an understanding of its interactions with the broader neuroendocrine system. Progesterone does not act in isolation. Its effects are intricately linked with those of other steroid hormones, particularly estrogen and testosterone.

The interplay between these hormones creates a complex and dynamic environment that influences everything from synaptic function to gene expression. For instance, progesterone can modulate the expression of estrogen receptors in the brain, thereby influencing the brain’s sensitivity to estrogen’s neuroprotective effects. This intricate dance of hormones is a key area of research in the quest to understand and optimize cognitive aging.

What Are the Neurobiological Mechanisms of Progesterone Action?

At the molecular level, progesterone exerts its effects through both genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic pathway involves the binding of progesterone to intracellular receptors, which then travel to the cell nucleus and regulate gene expression. This process is relatively slow, taking hours to days to manifest its effects.

The non-genomic pathway, on the other hand, involves the binding of progesterone to membrane-bound receptors, leading to rapid changes in cellular function. This dual-action capability allows progesterone to have both long-lasting and immediate effects on brain function. For example, its rapid, non-genomic effects on GABA receptors contribute to its anxiolytic and sedative properties, while its slower, genomic effects are involved in processes like myelination and neurogenesis.

The long-term cognitive benefits of progesterone therapy are likely influenced by a complex interplay of genetic factors, hormonal interactions, and the timing of intervention.

The long-term cognitive outcomes of progesterone therapy are also influenced by an individual’s genetic makeup. Variations in genes that code for hormone receptors, metabolic enzymes, and growth factors can all affect an individual’s response to hormone therapy.

For example, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, has been shown to interact with hormone therapy to influence cognitive outcomes. Individuals with the APOE4 allele may respond differently to progesterone therapy than those with other variants of the gene. This highlights the importance of a personalized approach to hormone therapy, one that takes into account an individual’s unique genetic profile.

Future Directions in Progesterone Research

The field of progesterone research is continually evolving. Current studies are exploring the potential of progesterone and its metabolites, such as allopregnanolone, as therapeutic agents for a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, and depression.

There is also growing interest in the development of selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) that could offer the cognitive benefits of progesterone with fewer side effects. As our understanding of progesterone’s complex role in the brain deepens, so too will our ability to harness its therapeutic potential for the preservation of cognitive health throughout the lifespan.

The following table summarizes some of the key areas of ongoing research into progesterone and cognitive function:

| Area of Research | Focus | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroinflammation | Investigating progesterone’s ability to reduce inflammatory processes in the brain. | Prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. |

| Myelin Repair | Exploring progesterone’s role in promoting the formation and repair of the myelin sheath. | Treatment of demyelinating disorders like multiple sclerosis. |

| Synaptic Plasticity | Examining how progesterone influences the connections between neurons. | Enhancement of learning and memory. |

References

- Gleason, C. E. et al. “Long-term cognitive effects of menopausal hormone therapy ∞ Findings from the KEEPS Continuation Study.” PLoS Medicine, vol. 18, no. 3, 2021, e1003533.

- Berent-Spillson, A. et al. “Distinct cognitive effects of estrogen and progesterone in recently menopausal women.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 59, 2015, pp. 25-36.

- Brinton, R. D. “Progesterone in prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease ∞ a new hope for women.” Endocrinology, vol. 150, no. 6, 2009, pp. 2561-2565.

- Shumaker, S. A. et al. “Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women ∞ the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study ∞ a randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, vol. 289, no. 20, 2003, pp. 2651-2662.

- Singh, M. and Su, C. “Progesterone and its metabolites ∞ neuroprotective and promising therapeutic strategies for traumatic brain injury.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 14, no. 3, 2013, pp. 5699-5716.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a window into the intricate relationship between progesterone and cognitive health. It is a starting point for a deeper conversation with yourself and with a qualified healthcare provider. Your personal health narrative is unique, and the path forward will be equally individualized.

The knowledge you have gained is a tool, empowering you to ask precise questions and to advocate for a wellness strategy that aligns with your body’s specific needs. The ultimate goal is a state of vitality and function that allows you to engage with your life fully and without compromise. This journey of understanding your own biology is a powerful act of self-stewardship.