Fundamentals

The experience of cognitive change during the menopausal transition is a profound and personal one. You may notice a subtle shift in your ability to recall a word, a momentary lapse in focus during a meeting, or a general feeling of mental fog that clouds your day.

These moments are real, they are biologically driven, and they originate from the intricate recalibration of your body’s internal communication network. Understanding the long-term cognitive landscape in relation to early menopausal hormone therapy begins with acknowledging these lived experiences and connecting them to the underlying physiology.

The question of what hormonal support can offer the brain is a journey into the very architecture of your neurobiology, where hormones like estrogen act as master regulators of cellular energy, connectivity, and resilience.

Your brain is the most metabolically active organ in your body, and it is exquisitely sensitive to its hormonal environment. Estrogen, specifically estradiol (E2), is a key modulator of brain function. It influences everything from the production of neurotransmitters, the chemical messengers that allow brain cells to communicate, to the very structure of the neurons themselves.

During your reproductive years, your brain becomes accustomed to a relatively stable, cyclical supply of estrogen. As you enter perimenopause and menopause, the decline and fluctuation of this vital hormone can disrupt the delicate balance of your neural circuits. This disruption is often what you perceive as brain fog, memory lapses, or difficulty with multitasking. It is a physiological response to a changing internal environment, a signal that your brain is adapting to a new hormonal reality.

The Brain’s Relationship with Estrogen

To appreciate the conversation around hormone therapy and cognition, we must first understand the deep, symbiotic relationship between estrogen and the brain. Estradiol is not merely a reproductive hormone; it is a powerful neuroprotective agent. It supports the health and function of neurons in several key ways.

It promotes synaptic plasticity, which is the ability of your brain to form new connections and learn new information. It also enhances cerebral blood flow, ensuring that your brain receives the oxygen and nutrients it needs to perform at its best. Furthermore, estrogen has anti-inflammatory properties and helps protect neurons from oxidative stress, a form of cellular damage that can accumulate over time.

When estrogen levels decline during menopause, the brain loses a significant degree of this protective and supportive influence. This can lead to a state of increased vulnerability, where neurons may be more susceptible to age-related changes.

The “critical window” hypothesis, a central concept in this field, proposes that there is a specific period, typically in early menopause, during which the brain is still receptive to the benefits of estrogen replacement. During this window, initiating hormone therapy may help preserve the underlying neural architecture that supports cognitive function.

After this window closes, the brain may have already undergone structural and functional changes that make it less responsive to estrogen, and in some cases, hormone therapy may even be detrimental.

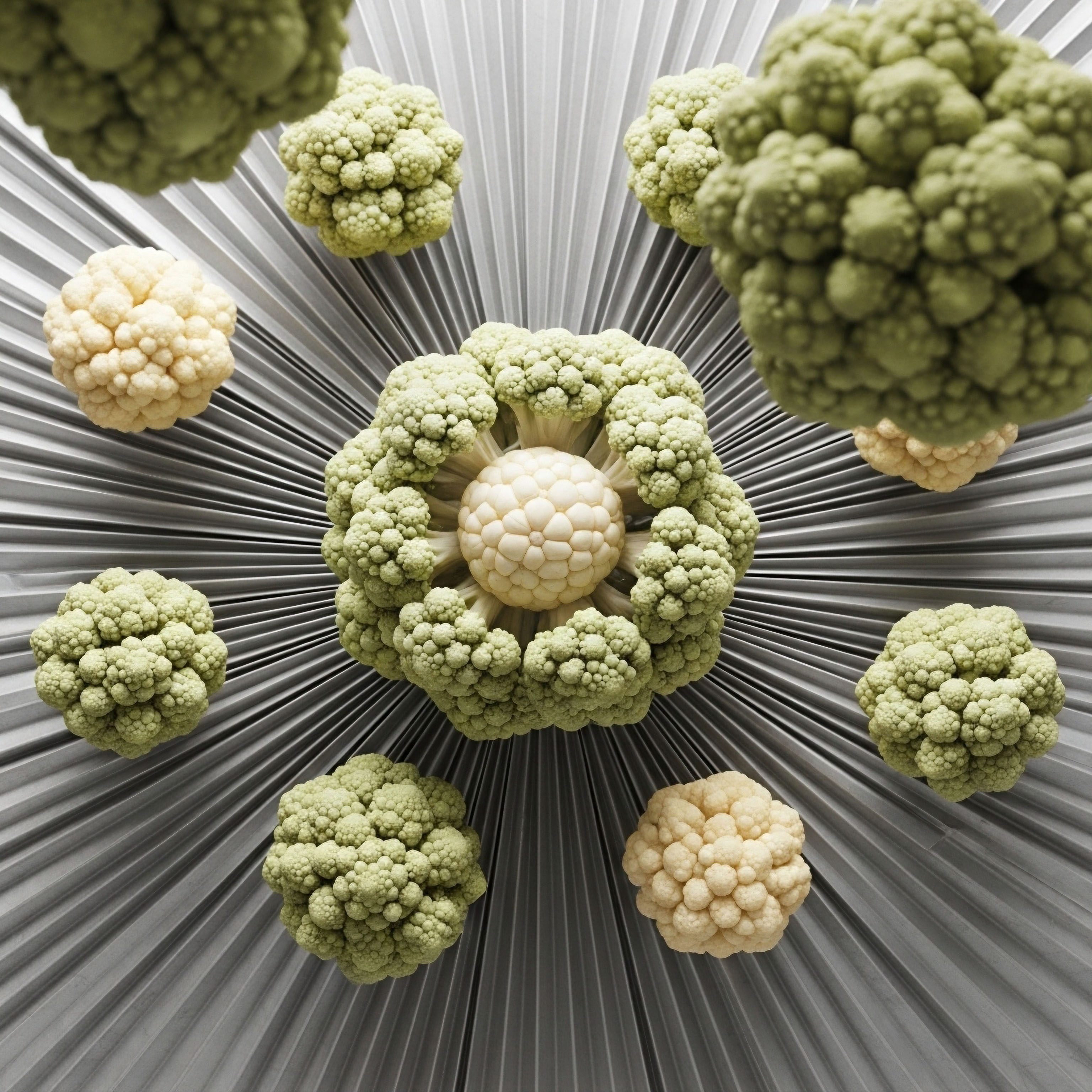

The brain’s intricate network of neurons relies on estrogen as a key conductor, orchestrating cellular energy and communication pathways that underpin cognitive clarity.

Understanding Cognitive Domains

When we discuss “cognition,” we are referring to a collection of distinct mental abilities. It is a broad term that encompasses several specific domains, each of which can be affected differently by hormonal changes. Recognizing these domains helps to create a more precise understanding of the cognitive shifts you may be experiencing.

- Verbal Memory ∞ This involves the ability to recall words and language-based information. You might notice this as difficulty finding the right word in a conversation or remembering details from something you recently read.

- Executive Function ∞ This is a set of higher-order mental processes that includes planning, problem-solving, decision-making, and multitasking. A decline in executive function can manifest as feeling overwhelmed by complex tasks or having trouble organizing your thoughts.

- Processing Speed ∞ This refers to how quickly you can take in new information, process it, and respond. A slowing of processing speed can make you feel like your thinking is less sharp or that you are a step behind in fast-paced situations.

- Attention and Concentration ∞ This is the ability to focus on a task while filtering out distractions. Hormonal fluctuations can make it more challenging to maintain focus, leading to a feeling of being easily distracted or having a shorter attention span.

Each of these cognitive domains relies on specific neural circuits that are influenced by estrogen. The changes you feel are a direct reflection of alterations in the function of these circuits. Therefore, the goal of any intervention is to support the health and efficiency of these underlying biological systems.

The Foundational Role of Hormonal Balance

While estrogen is a primary focus in the context of menopause, it is important to view the endocrine system as a whole. Hormones do not operate in isolation; they exist in a complex and interconnected network. Your cognitive function is influenced not just by estrogen, but also by progesterone, testosterone, thyroid hormones, and cortisol.

The menopausal transition represents a shift in the entire hormonal symphony, and achieving a sense of well-being often involves addressing the balance of this entire system.

Progesterone, for example, has a calming effect on the brain and can promote restful sleep, which is essential for cognitive consolidation and restoration. Testosterone, while often associated with men, is also a vital hormone for women, contributing to mental clarity, motivation, and a sense of vitality.

An imbalance in thyroid hormones can mimic many of the cognitive symptoms of menopause, leading to brain fog and fatigue. Similarly, chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels can have a detrimental effect on memory and executive function. A truly comprehensive approach to cognitive wellness during this life stage considers the interplay of all these factors, aiming to restore a state of systemic balance that allows your brain to function optimally.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of estrogen’s role in the brain, we can now examine the specific clinical evidence surrounding early menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) and its long-term cognitive outcomes. The central question for many women and their clinicians is whether initiating hormonal support shortly after the final menstrual period can confer lasting protection against cognitive decline.

This question has been the subject of rigorous scientific investigation, most notably through studies like the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) and its long-term follow-up, the KEEPS Continuation Study. These trials were specifically designed to address the “critical window” hypothesis and provide clarity for women making decisions about MHT in their early postmenopausal years.

The results of these landmark studies provide a clear and consistent message ∞ for healthy women who initiate MHT within the first few years of menopause, there appears to be no significant long-term cognitive benefit or harm.

This finding is incredibly reassuring from a safety perspective, as it alleviates concerns that MHT might increase the risk of cognitive decline when started at the appropriate time. However, it also tempers expectations that hormone therapy can serve as a primary strategy for preserving cognitive function into later life.

The data suggests that while MHT is highly effective for managing vasomotor symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats, its role in long-term cognitive preservation is neutral. The strongest predictor of cognitive performance in later life remains an individual’s cognitive function at baseline, before or during the menopausal transition itself.

Dissecting the Clinical Protocols

To fully grasp the implications of the KEEPS findings, it is essential to understand the specific hormonal formulations that were studied. The trial compared two different types of estrogen against a placebo, allowing for a nuanced analysis of how different delivery methods and molecular structures might affect the brain. This level of detail is critical for applying the research to real-world clinical practice.

Types of Estrogen Used in Key Studies

The KEEPS trial meticulously compared the two most common forms of estrogen therapy used in clinical practice, each with a distinct profile.

- Oral Conjugated Equine Estrogens (oCEE) ∞ This formulation, derived from pregnant mares’ urine, contains a mixture of different types of estrogens. It is taken orally, which means it must first pass through the liver before entering the systemic circulation. This “first-pass metabolism” can affect the production of various proteins and lipids, which has implications for cardiovascular health and other systemic effects.

- Transdermal 17β-Estradiol (tE2) ∞ This is a bioidentical form of estrogen, meaning it is structurally identical to the estradiol produced by the human ovary. It is delivered via a skin patch, which allows the hormone to be absorbed directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the liver. This delivery method results in a different metabolic profile compared to oral estrogens and was hypothesized to potentially have a more favorable impact on the brain.

In the KEEPS trial, both estrogen groups also received cyclic micronized progesterone to protect the uterine lining. The inclusion of a placebo group, where participants received an inactive pill and patch, was essential for isolating the true effects of the hormonal interventions from any potential placebo effect or other confounding factors.

Landmark clinical trials indicate that early menopausal hormone therapy is cognitively neutral in the long term, offering safety reassurance without providing a shield against age-related cognitive changes.

Comparing KEEPS with the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS)

The reassuring findings from KEEPS stand in contrast to the earlier results of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), which reported an increased risk of dementia in women who initiated hormone therapy at age 65 or older. This apparent contradiction is explained by the critical window hypothesis. The table below outlines the key differences between these two pivotal studies, highlighting why timing is everything when it comes to hormone therapy and the brain.

| Feature | KEEPS (Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study) | WHIMS (Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study) |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Age at Initiation | Early postmenopause (average age 52.6) | Late postmenopause (average age 71) |

| Time Since Menopause | Within 3 years of final menstrual period | 10+ years past menopause |

| Primary Estrogen Types Studied | Oral conjugated equine estrogens (oCEE) and transdermal 17β-estradiol (tE2) | Oral conjugated equine estrogens (oCEE) only |

| Primary Cognitive Outcome | No long-term benefit or harm to cognitive function | Increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia |

| Implication | Supports the neurocognitive safety of MHT when initiated in early menopause for symptom management. | Demonstrates potential cognitive risks when MHT is initiated in late postmenopause. |

The divergent outcomes of these two studies underscore a crucial biological principle ∞ the brain’s receptivity to estrogen changes with age and time since menopause. In the early postmenopausal period, the neural machinery that responds to estrogen is still largely intact. Introducing hormone therapy at this stage appears to be safe from a cognitive standpoint.

However, in later years, the brain has already adapted to a low-estrogen environment, and reintroducing hormones may disrupt this new equilibrium, potentially leading to adverse effects. This is why the decision to initiate MHT is highly individualized and depends heavily on a woman’s age and specific health profile.

What Are the Implications for Testosterone and Peptide Therapies?

While estrogen-based MHT may not be a tool for long-term cognitive enhancement, this does not mean that hormonal optimization is irrelevant for brain health. A comprehensive approach looks at the entire endocrine system. For many women, particularly during perimenopause and postmenopause, low testosterone levels can contribute significantly to symptoms of cognitive fatigue, low motivation, and a diminished sense of well-being.

Judicious use of testosterone therapy in women, typically in low doses, can help restore mental clarity and drive. This is not about achieving supraphysiological levels, but about returning the body to a state of hormonal balance that supports optimal function.

Similarly, growth hormone peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin/CJC-1295, can play a supportive role. These peptides stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone, which is essential for cellular repair, sleep quality, and metabolic health.

Improved sleep, in particular, has a direct and profound impact on cognitive function, as it is during deep sleep that the brain clears metabolic waste and consolidates memories. By addressing these other hormonal axes, we can create a biological environment that is more resilient and supportive of overall brain health, even if estrogen’s primary role remains symptom management.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term cognitive effects of early menopausal hormone therapy requires a deep dive into the molecular neurobiology of estrogen and a critical analysis of the clinical trial data that informs our current understanding.

The prevailing evidence, largely anchored by the KEEPS Continuation Study, points toward a long-term neutrality of MHT on cognition when initiated within the critical window. To comprehend this outcome, we must move beyond a simple cause-and-effect framework and adopt a systems-biology perspective. This involves examining how estrogens interact with specific neural substrates, the temporal dynamics of these interactions, and the limitations of our current clinical models in capturing the full spectrum of cognitive aging.

The central dogma that has emerged is the “critical window” or “timing hypothesis,” which posits that the neuroprotective effects of estrogen are contingent upon the health and receptivity of the underlying neural tissue. In the early postmenopausal brain, estrogen receptors are still abundant and functional, and the cellular machinery for synaptic plasticity and metabolic regulation is largely intact.

In this state, exogenous estrogen may act to preserve existing function and mitigate the immediate consequences of hormone withdrawal. However, prolonged estrogen deprivation, as seen in women who are many years post-menopause, leads to irreversible changes, including a downregulation of estrogen receptors and a shift in cellular metabolism. Attempting to introduce estrogen into this altered environment may fail to produce benefits and could even trigger maladaptive responses, as suggested by the WHIMS data.

Molecular Mechanisms of Estrogen Action in the Brain

Estrogen’s influence on the central nervous system is mediated through a complex array of genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways. These actions are primarily initiated by the binding of estradiol to two main estrogen receptor subtypes, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), which are differentially expressed throughout the brain. Their distribution in key cognitive areas like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex forms the biological basis for estrogen’s role in memory and executive function.

Genomic Vs Non-Genomic Pathways

The classical mechanism of estrogen action is genomic. Estradiol diffuses across the cell membrane and binds to ERα or ERβ in the cytoplasm or nucleus. This hormone-receptor complex then translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences known as estrogen response elements (EREs).

This binding event modulates the transcription of target genes, leading to the synthesis of proteins that are involved in neuronal survival, synaptic growth, and neurotransmission. This is a relatively slow process, taking hours to days to manifest its effects.

In contrast, non-genomic pathways involve the rapid activation of signaling cascades at the cell membrane. A subpopulation of estrogen receptors is located at the plasma membrane, where they can interact with and modulate the activity of various kinases and signaling molecules.

These rapid, non-transcriptional effects can influence synaptic function and neuronal excitability on a timescale of seconds to minutes. It is this rapid signaling that is thought to underlie some of estrogen’s more immediate effects on mood and cognitive processing. The interplay between these two pathways creates a dynamic and multifaceted system of regulation that is difficult to fully replicate with exogenous hormone therapy.

A Deeper Look at the KEEPS Continuation Study

The KEEPS Continuation Study provides the most robust longitudinal data on this topic. Its design and statistical analysis offer valuable insights into why a long-term cognitive benefit was not observed. The study employed Latent Growth Models (LGMs) to analyze the trajectory of cognitive change over time, a sophisticated statistical technique that allows researchers to model individual differences in cognitive performance at baseline and how that performance changes over the years.

The LGM analysis revealed that the single strongest predictor of cognitive function approximately 10 years after the trial was the participant’s cognitive score at the beginning of the study. The rate of cognitive change during the initial four-year trial period was also a significant predictor.

Crucially, the type of treatment received (oCEE, tE2, or placebo) had no statistically significant effect on the long-term cognitive trajectory. This suggests that while MHT may have subtle, short-term effects, these effects do not compound over time to produce a lasting advantage. The brain’s cognitive reserve and its inherent rate of aging appear to be far more powerful determinants of long-term outcomes than a four-year course of early MHT.

Statistical modeling of longitudinal data reveals that baseline cognitive status is a more powerful predictor of long-term function than the administration of early menopausal hormone therapy.

What Are the Unresolved Questions in MHT and Brain Aging?

Despite the clarity provided by KEEPS, several important questions remain unanswered. The KEEPS cohort consisted of healthy women with a low cardiovascular risk profile. It is unknown whether these findings can be generalized to women with other health conditions, such as metabolic syndrome or a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease.

The APOE4 allele, for example, is a major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s, and some research suggests that it may interact with hormone therapy, although the nature of this interaction is still a subject of debate. Future research is needed to explore how MHT affects cognitive aging in these more vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, the optimal formulation, dose, and duration of MHT for brain health are still not fully understood. While KEEPS found no difference between oral and transdermal estrogen, other studies have suggested that transdermal delivery may have a more favorable risk profile.

The role of progestogens is also an area of active investigation, as different synthetic progestins can have varying effects on the brain. The development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) that can target specific estrogen pathways in the brain without affecting other tissues represents a promising avenue for future therapeutic development.

| Biological Domain | Specific Action of Estradiol | Relevance to Cognition |

|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Plasticity | Increases dendritic spine density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. | Enhances the capacity for learning, memory formation, and cognitive flexibility. |

| Neurotransmission | Modulates the synthesis and release of acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin. | Affects attention, mood, motivation, and executive function. |

| Cerebral Metabolism | Promotes glucose transport and utilization in key brain regions. | Supports the high energy demands of neuronal activity and cognitive processing. |

| Neuroprotection | Exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, reducing neuronal damage. | Preserves the structural integrity of the brain and may buffer against age-related decline. |

References

- Gleason, C. E. et al. “Hormone therapy in early menopause proves safe but lacks cognitive benefits.” News-Medical.Net, 2024.

- Miller, V. M. et al. “Long-term cognitive effects of menopausal hormone therapy ∞ Findings from the KEEPS Continuation Study.” PubMed, 2024.

- Wharton, W. et al. “Long-term cognitive effects of menopausal hormone therapy ∞ Findings from the KEEPS Continuation Study.” PLOS Medicine, vol. 21, no. 6, 2024, e1004422.

- Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. “Does menopausal hormone therapy affect long-term cognitive function?” Cognitive Vitality Reports, 2025.

- National Institute on Aging. “Estrogen therapy has no long-term effect on cognition in younger postmenopausal women.” National Institutes of Health, 2013.

Reflection

The journey through the clinical science of hormone therapy and cognition ultimately leads back to a deeply personal place. The data provides a framework, a map of what is known and what remains to be discovered.

We have seen that for many healthy women, initiating hormone therapy in early menopause is a safe choice for managing physical symptoms, yet it is not the definitive answer for preserving long-term cognitive function. This understanding shifts the focus. It moves us from seeking a single intervention to embracing a more holistic and proactive stewardship of our own neurological health.

Consider the intricate systems within your own body. Your cognitive vitality is not solely dependent on estrogen. It is woven into the quality of your sleep, the stability of your metabolic health, the resilience of your stress response, and the overall balance of your endocrine system.

The knowledge that a single therapy does not hold all the answers is empowering. It opens the door to a more comprehensive approach, one where you become an active participant in your own well-being. What are the foundational pillars of your health that you can support today? How can you cultivate a lifestyle that fosters cognitive resilience, independent of any single protocol?

This information is not an endpoint. It is a starting point for a more informed conversation with yourself and with your healthcare provider. The path forward is one of personalized medicine, where your unique biology, your personal history, and your future goals inform every decision. The ultimate aim is to cultivate a state of sustained vitality, where your mind remains a clear, capable, and vibrant partner throughout your life.