Fundamentals

You may be reading this because you feel a shift within your own body. Perhaps it is a subtle loss of energy, a change in mood, or a feeling that your internal vitality has diminished. These experiences are valid, and they often point toward the intricate communication network that governs our biology the endocrine system.

Understanding the long-term cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy begins with appreciating your body as a finely tuned orchestra, where each hormone plays a critical part. The conversation about testosterone is a conversation about restoring systemic balance and function, allowing your biology to perform as it was designed.

At the center of male hormonal health is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This is the command-and-control pathway for testosterone production. The hypothalamus, a small region in your brain, acts as the system’s CEO. It sends a chemical message, Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), to the pituitary gland.

The pituitary, acting as a middle manager, then releases two other messengers into the bloodstream Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH is the direct signal that travels to the Leydig cells in the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone. This entire system operates on a sophisticated feedback loop.

When testosterone levels are sufficient, they send a signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to slow down the release of GnRH and LH, maintaining a state of equilibrium. When this axis is disrupted by age, stress, or other health factors, that equilibrium is lost, and the symptoms of low testosterone can begin to surface.

The Role of Testosterone beyond Muscle

Testosterone’s role in the body extends far beyond its well-known effects on muscle mass and libido. It is a foundational molecule for systemic health, actively participating in the function of numerous tissues, including the cardiovascular system. It contributes to maintaining bone density, regulating mood and cognitive function, and supporting the production of red blood cells.

Within the cardiovascular system, testosterone interacts with blood vessels, helping to facilitate blood flow through mechanisms related to nitric oxide production. It also influences the health of the heart muscle itself. Therefore, when we discuss optimizing testosterone levels, we are addressing a molecule that is deeply integrated into the fabric of male physiology. The goal of a well-designed protocol is to return the body to its optimal state of function, where these processes are properly supported.

Why the Question of Cardiovascular Safety Arose

The discussion around testosterone therapy and cardiovascular health has been present for years. Some earlier, often smaller, and methodologically limited studies produced conflicting results that created uncertainty. These inconsistencies prompted the medical and scientific communities to seek more definitive answers.

In response, large-scale, rigorously designed clinical trials were initiated to provide a much clearer picture of the safety profile of testosterone therapy in men with clinically diagnosed hypogonadism. These modern studies, such as the landmark TRAVERSE trial, were specifically designed to assess cardiovascular outcomes with a high degree of statistical power and reliability, moving the conversation from speculation to evidence-based understanding.

Understanding testosterone’s role in the body is the first step toward evaluating the safety and efficacy of hormonal therapy.

Evaluating the long-term safety of any therapeutic protocol requires a clear framework. In the context of testosterone therapy, researchers focus on a set of specific and measurable cardiovascular outcomes. These are the data points that allow clinicians to build a comprehensive risk profile and make informed decisions.

The primary points of evaluation are Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, or MACE, which is a composite measure including death from cardiovascular causes, non-fatal heart attacks, and non-fatal strokes. Additionally, scientists closely examine the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Finally, a critical component of long-term monitoring involves tracking changes in key biological markers, such as hematocrit (the concentration of red blood cells) and lipid profiles, as these can be influenced by testosterone and have downstream effects on cardiovascular health.

Intermediate

As we move into a more detailed analysis of testosterone therapy, we must examine the specific biological mechanisms through which it interacts with the cardiovascular system. This level of understanding moves us from the general to the specific, revealing how hormonal optimization protocols are designed to maximize benefits while actively managing potential risks.

The two most significant physiological considerations in this context are the therapy’s effect on red blood cell production, a process known as erythropoiesis, and its influence on lipid metabolism. Both are predictable and manageable phenomena when monitored correctly within a clinical framework.

How Does Testosterone Influence Blood Composition?

One of the most well-documented effects of testosterone therapy is its stimulation of the bone marrow to produce more red blood cells. This process is primarily mediated by an increase in the hormone erythropoietin (EPO), which is the principal driver of red blood cell creation.

Testosterone also appears to improve the availability of iron for this process by suppressing a protein called hepcidin, which normally sequesters iron. The resulting increase in the volume of red blood cells relative to the total blood volume is measured as hematocrit.

While a healthy red blood cell count is essential for oxygen transport, a significant elevation in hematocrit can make the blood more viscous, or thicker. This change in blood consistency is a primary factor in the potential for increased thrombotic risk, as thicker fluid can, in theory, be more prone to clotting.

Erythrocytosis and Thrombotic Risk Management

The clinical term for an elevated hematocrit is erythrocytosis. Studies have shown an association between therapy-induced erythrocytosis and a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. An observational study noted that men who developed erythrocytosis on therapy had a higher risk of major adverse cardiac events and VTE.

This underscores the absolute necessity of regular blood monitoring. For symptomatic patients with a hematocrit value over 54%, clinical guidelines often recommend discontinuing therapy until levels normalize, and phlebotomy (the clinical removal of blood) may be considered. This proactive management is a standard part of a responsible hormonal optimization protocol, turning a potential risk into a manageable variable.

The risk of erythrocytosis also appears to be dose-dependent and can be more pronounced in older men. This is why a “start low and go slow” approach to dosing is often clinically prudent, alongside regular monitoring to establish the individual’s response to therapy. A structured monitoring schedule is the cornerstone of safe application.

| Time Point | Action Required | Clinical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Measure hematocrit before initiating therapy. |

Establishes the patient’s starting point and identifies any pre-existing conditions. |

| 3 Months |

Re-measure hematocrit. |

Captures the initial physiological response to therapy, as hematocrit can rise within the first few months. |

| 6 Months |

Re-measure hematocrit. |

Confirms the trend and allows for dose adjustments if levels are rising too quickly. |

| Annually |

Measure hematocrit as part of routine labs. |

Ensures long-term stability and safety, with more frequent checks if the dose is adjusted or if levels approach the upper limit of the normal range. |

The Complex Relationship with Lipid Metabolism

The interaction between testosterone and cholesterol is nuanced. Naturally occurring, or endogenous, testosterone levels are generally associated with a more favorable, anti-atherogenic lipid profile, including higher levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and lower levels of triglycerides and total cholesterol.

HDL is often referred to as “good cholesterol” because it helps remove cholesterol from arteries, transporting it back to the liver for processing. However, the administration of exogenous testosterone can sometimes lead to a decrease in HDL cholesterol levels. This effect has historically been a point of concern regarding cardiovascular safety.

Beyond the Numbers HDL Function and Particle Size

Modern lipidology is revealing that the total amount of HDL cholesterol may be a less important predictor of cardiovascular risk than the quality and function of the HDL particles themselves. HDL exists in different subfractions, with larger, more buoyant particles (HDL2) considered more protective than smaller, denser particles (HDL3).

Some research indicates that while testosterone therapy might lower the total HDL number, it may not negatively affect the more protective subfraactions. Furthermore, the focus is shifting toward other markers like Apolipoprotein B (ApoB), which is a direct measure of the number of atherogenic (plaque-forming) particles, such as low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

Many experts now consider ApoB to be a more accurate predictor of cardiovascular risk than traditional LDL cholesterol measurements. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of cardiovascular risk on therapy involves looking beyond a single number and evaluating the entire lipid landscape.

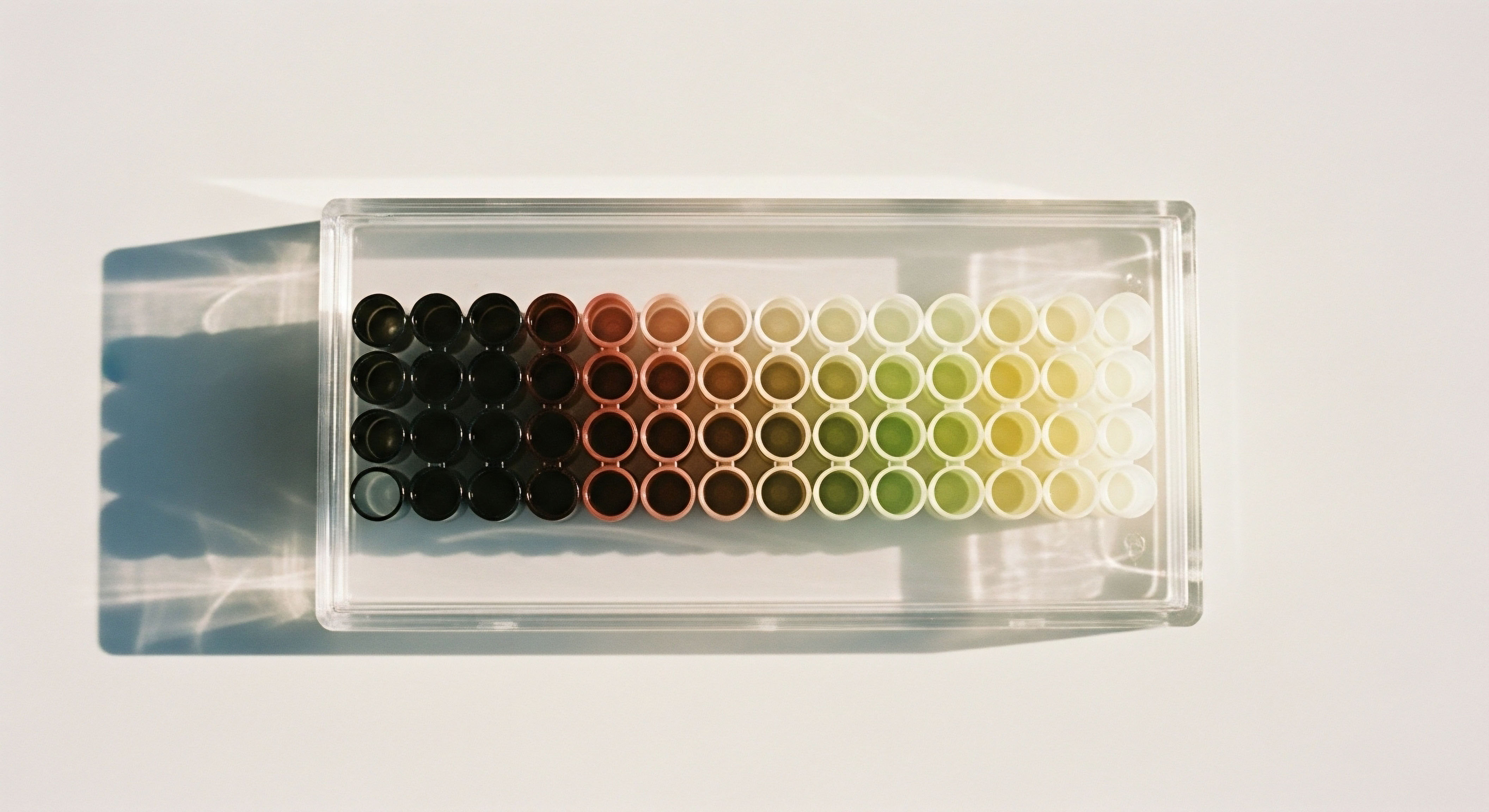

Effective management of testosterone therapy involves monitoring key biomarkers to ensure the body remains in a state of optimal balance.

A properly managed hormonal optimization protocol will include a comprehensive panel of cardiovascular markers to create a complete picture of an individual’s health. This allows for a proactive and personalized approach to wellness.

- Advanced Lipid Panel ∞ This should include standard measures like Total Cholesterol, LDL, and HDL, but also Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) to quantify the number of plaque-forming particles directly.

- Inflammatory Markers ∞ High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) is a key marker of systemic inflammation, which is a known driver of atherosclerosis.

- Hematocrit and Hemoglobin ∞ As discussed, these are essential for monitoring red blood cell production and managing the risk of erythrocytosis.

- Metabolic Markers ∞ Fasting glucose and HbA1c are critical for assessing blood sugar control and insulin sensitivity, which are deeply intertwined with cardiovascular health.

Academic

The highest level of clinical evidence for determining the safety of a therapeutic intervention comes from large, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs). For many years, the clinical community lacked such a definitive study regarding the cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy.

This evidence gap was substantially addressed by the Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Assessment of Long-term Vascular Events and Efficacy Response in Hypogonadal Men (TRAVERSE) trial. The results of this landmark study provide the most robust data to date and are central to any academic discussion of the topic.

What Does the Landmark TRAVERSE Trial Reveal?

The TRAVERSE trial was specifically designed at the request of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to clarify the cardiovascular risks associated with testosterone therapy. It was a large-scale study, enrolling 5,204 men between the ages of 45 and 80. All participants had pre-existing cardiovascular disease or a high number of risk factors for it.

Critically, they also had symptomatic hypogonadism, confirmed by two separate morning testosterone measurements below 300 ng/dL. The men were randomly assigned to receive either a daily 1.62% testosterone gel or a matching placebo gel. The dose of the testosterone gel was adjusted to maintain serum levels within a physiologic range (350 to 750 ng/dL). The mean duration of treatment was just under two years, with a total follow-up period of about three years.

Analysis of the Primary Cardiovascular Endpoint

The primary safety endpoint of the TRAVERSE trial was a composite of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of death from cardiovascular causes, a non-fatal myocardial infarction (heart attack), or a non-fatal stroke. The results were clear and statistically significant.

The study found that testosterone therapy was non-inferior to placebo with respect to the incidence of these major adverse cardiac events. The primary endpoint occurred in 7.0% of the men in the testosterone group, compared to 7.3% in the placebo group.

This finding provides a high degree of reassurance that for middle-aged and older men with confirmed hypogonadism and elevated cardiovascular risk, testosterone therapy administered to achieve physiologic levels does not increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, or cardiovascular death over a medium-term follow-up period.

The TRAVERSE trial demonstrated that testosterone therapy did not increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events in men with hypogonadism and high cardiovascular risk.

Secondary Endpoints a More Nuanced Safety Profile

While the primary endpoint results were reassuring, a detailed analysis of the secondary safety endpoints revealed a more complex picture. The trial showed a statistically significant increase in the incidence of a few specific adverse events in the testosterone group compared to the placebo group. These included:

- Atrial Fibrillation ∞ The incidence of atrial fibrillation, an irregular and often rapid heart rate, was higher in the testosterone group (3.5%) versus the placebo group (2.4%).

- Pulmonary Embolism ∞ There was a small but statistically significant increase in pulmonary embolism, a type of blood clot in the lungs (0.9% vs. 0.5%). This finding is consistent with the known risk of VTE associated with testosterone-induced erythrocytosis.

- Acute Kidney Injury ∞ An unexpected finding was a higher rate of acute kidney injury in the testosterone group (2.3% vs. 1.5%).

These findings are critical for a balanced clinical discussion. They suggest that while the risk of MACE is not elevated, the therapy is not without potential adverse effects that require careful patient selection and monitoring. For instance, the findings support exercising caution when considering therapy for men with a prior history of thromboembolic events or significant pre-existing arrhythmias.

| Outcome | Testosterone Group Incidence | Placebo Group Incidence | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary MACE Endpoint |

7.0% |

7.3% |

0.96 (0.78-1.17) |

Non-inferiority met; no increased risk of heart attack, stroke, or CV death. |

| Atrial Fibrillation |

3.5% |

2.4% |

N/A (p=0.02) |

|

| Pulmonary Embolism |

0.9% |

0.5% |

N/A (p-value not specified in source) |

Statistically significant increased incidence. |

| Acute Kidney Injury |

2.3% |

1.5% |

N/A (p=0.04) |

Statistically significant increased incidence. |

What Are the Unresolved Questions and Future Directions?

The TRAVERSE trial represents a monumental step forward, but it does not answer every question. The mean follow-up was approximately three years, so the effects of therapy beyond this timeframe remain to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, the study population was specific ∞ middle-aged and older men with high pre-existing cardiovascular risk.

The results are most directly applicable to this group and should not be extrapolated to younger men or those using testosterone for non-medical, performance-enhancement purposes, often at much higher, supraphysiologic doses. The findings on atrial fibrillation and acute kidney injury also warrant further investigation to understand the underlying mechanisms.

Future research will likely focus on longer-term outcomes and identifying patient characteristics that might predict both the benefits and the risks of therapy more precisely. This ongoing scientific process continuously refines our understanding and improves the safety and efficacy of clinical protocols.

References

- Lincoff, A. M. et al. “Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine, 2023.

- Braga, Marcelo, et al. “Long-Term Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy in Middle-Aged and Older Men ∞ A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs, 2025.

- Khera, Mohit. “Long Term Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone Therapy ∞ A Review of the TRAVERSE Study.” The Journal of Urology, 2025.

- Delev, D. “Testosterone therapy-induced erythrocytosis ∞ can phlebotomy be justified?.” Annals of Translational Medicine, 2022.

- Al-Zoubi, R. M. et al. “Testosterone use causing erythrocytosis.” CMAJ, 2018.

- Anaissie, J. et al. “An update on testosterone, HDL and cardiovascular risk in men.” Future Science OA, 2015.

- Gagliano-Jucá, T. & Basaria, S. “Testosterone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease.” Nature Reviews Cardiology, 2019.

- Shoskes, J. J. et al. “Pharmacology of testosterone replacement therapy preparations.” Translational Andrology and Urology, 2016.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here, from foundational biology to the details of landmark clinical trials, provides a map. It offers coordinates and landmarks based on extensive scientific research. This map gives you the power of knowledge, transforming abstract concerns into understandable, manageable concepts. You now have a framework for understanding how your internal systems operate and how a therapeutic intervention interacts with that system. This knowledge is the essential first tool for any individual seeking to reclaim their vitality.

Your personal health narrative, however, is unique. The way your body responds to any protocol is based on your specific genetics, lifestyle, and health history. The data provides the science, but your experience provides the context. The path forward involves a partnership ∞ a dialogue between your lived experience and the objective data from clinical monitoring.

Consider this knowledge not as a final destination, but as the well-equipped starting point for a proactive and deeply personal exploration of your own potential for health and function.

Glossary

cardiovascular safety

testosterone therapy

red blood cells

traverse trial

hypogonadism

which includes deep vein thrombosis

death from cardiovascular causes

red blood cell production

lipid metabolism

includes deep vein thrombosis

major adverse cardiac events

erythrocytosis

older men

cardiovascular risk

apolipoprotein b

testosterone replacement therapy

the traverse trial

adverse cardiac events

major adverse cardiac

atrial fibrillation

pulmonary embolism

acute kidney injury

statistically significant increased incidence

statistically significant increased

significant increased incidence