Fundamentals

Have you found yourself feeling inexplicably tired, experiencing a persistent mental fog, or noticing changes in your body composition despite consistent efforts? Perhaps your sleep patterns have become disrupted, or your emotional equilibrium feels less stable than before. These subtle shifts, often dismissed as typical signs of aging or daily stress, frequently signal deeper biological changes within your endocrine system.

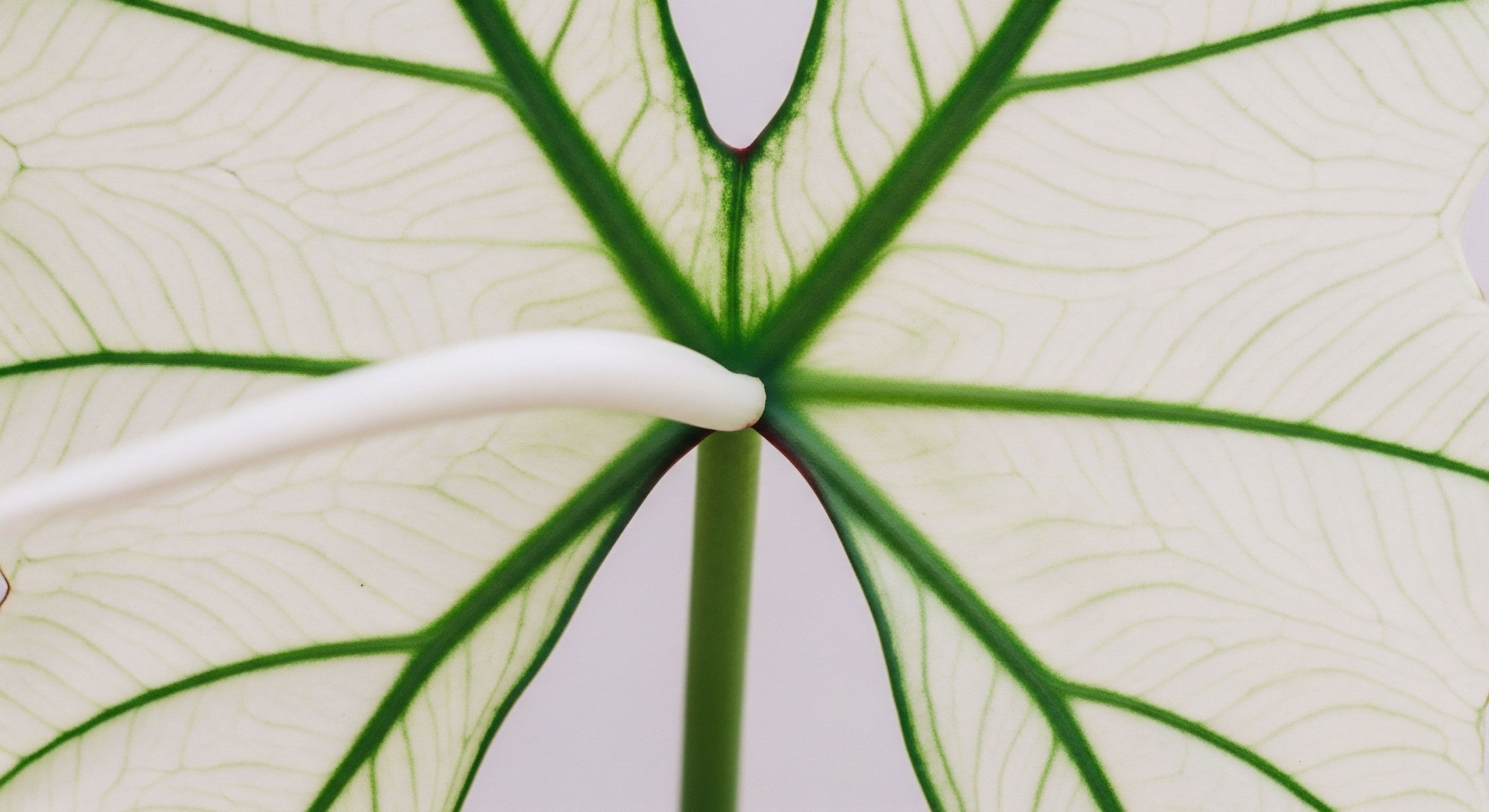

Your body communicates through a complex network of chemical messengers known as hormones. When these vital signals fall out of balance, the effects ripple throughout every system, including your cardiovascular health. Recognizing these early indicators marks the initial step toward reclaiming your vitality and safeguarding your long-term well-being.

The endocrine system, a sophisticated internal messaging service, directs nearly every physiological process. Hormones act as biological conductors, orchestrating functions from metabolism and mood to growth and reproduction. A delicate equilibrium among these chemical messengers is paramount for optimal health. When this balance is disturbed, even slightly, a cascade of systemic consequences can unfold. Unaddressed hormonal imbalances do not merely affect how you feel today; they exert a cumulative impact on your cardiovascular system over many years.

The Endocrine System and Cardiovascular Health

Your heart and blood vessels operate under the constant influence of various hormones. For instance, thyroid hormones regulate metabolic rate, directly influencing heart rate and blood pressure. Cortisol, a stress hormone, affects blood sugar regulation and inflammation, both of which contribute to cardiovascular risk. Sex hormones, such as testosterone and estrogen, play significant roles in maintaining vascular integrity and lipid profiles. A disruption in any of these hormonal pathways can initiate a silent, progressive decline in cardiovascular function.

Consider the widespread impact of declining testosterone levels in men, a condition often termed andropause. While commonly associated with reduced libido and muscle mass, low testosterone also correlates with adverse changes in cholesterol levels, increased abdominal adiposity, and impaired glucose metabolism. These metabolic disturbances collectively heighten the risk for atherosclerosis, a hardening and narrowing of the arteries.

Similarly, women navigating perimenopause and post-menopause experience significant fluctuations and declines in estrogen and progesterone. These hormonal shifts contribute to changes in lipid profiles, endothelial function, and systemic inflammation, directly affecting cardiovascular risk.

Hormonal equilibrium acts as a vital guardian for cardiovascular health, with imbalances silently increasing long-term risks.

Understanding Hormonal Feedback Loops

Hormonal systems operate through intricate feedback loops, similar to a home thermostat. When a hormone level drops, the brain’s hypothalamus and pituitary gland send signals to stimulate its production. Conversely, high levels trigger inhibitory signals. This constant communication ensures stability. Disruptions to this delicate regulatory mechanism, whether from aging, environmental factors, or chronic stress, can lead to sustained imbalances. These persistent deviations from optimal ranges can silently strain the cardiovascular system, contributing to conditions like hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance.

The body’s internal environment seeks a state of balance, known as homeostasis. Hormones are central to maintaining this state. When hormonal signals are consistently out of sync, the body adapts in ways that can be detrimental over time.

For example, chronic elevation of cortisol, often due to prolonged stress, can lead to sustained increases in blood pressure and blood sugar, placing additional burden on the heart and blood vessels. Understanding these fundamental connections helps clarify why addressing hormonal health is not merely about symptom relief, but about preserving long-term systemic function.

Intermediate

Addressing hormonal imbalances requires a precise, individualized strategy, moving beyond general wellness advice to targeted clinical protocols. These interventions aim to restore physiological balance, thereby mitigating the long-term cardiovascular risks associated with unaddressed hormonal dysregulation. The specific therapeutic agents and their application depend heavily on the individual’s unique biochemical profile, symptoms, and health objectives.

Targeted Hormonal Optimization Protocols

Hormonal optimization protocols are designed to recalibrate the endocrine system, bringing hormone levels back into optimal ranges. This approach considers the interconnectedness of various hormones and their systemic effects.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Men

For men experiencing symptoms of low testosterone, often termed hypogonadism or andropause, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) can be a transformative intervention. Low testosterone in men is associated with increased visceral fat, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction, all precursors to cardiovascular disease.

A standard protocol often involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate (200mg/ml). This method ensures consistent physiological levels, avoiding the peaks and troughs associated with less frequent dosing. To maintain the body’s natural testosterone production and preserve fertility, Gonadorelin is frequently administered via subcutaneous injections twice weekly. Gonadorelin stimulates the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which are essential for testicular function.

Another consideration in male hormonal optimization is managing estrogen conversion. Testosterone can convert into estrogen through the enzyme aromatase. Elevated estrogen levels in men can lead to undesirable side effects, including gynecomastia and water retention, and may also contribute to cardiovascular risk factors.

Therefore, an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is often prescribed as a twice-weekly oral tablet to block this conversion. Some protocols may also incorporate Enclomiphene to further support LH and FSH levels, particularly when fertility preservation is a primary concern.

Precision hormonal recalibration, such as TRT for men, directly addresses metabolic and vascular health markers, reducing cardiovascular strain.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Women

Women also experience the consequences of suboptimal testosterone levels, manifesting as irregular cycles, mood changes, hot flashes, and reduced libido. These symptoms often become more pronounced during perimenopause and post-menopause. Addressing these imbalances can significantly improve quality of life and metabolic markers.

Protocols for women typically involve lower doses of Testosterone Cypionate, often 10 ∞ 20 units (0.1 ∞ 0.2ml) weekly via subcutaneous injection. This micro-dosing approach aims to restore physiological levels without inducing masculinizing side effects. Progesterone is a critical component of female hormonal balance, prescribed based on menopausal status. In pre-menopausal and peri-menopausal women, progesterone helps regulate menstrual cycles and counter estrogen dominance. For post-menopausal women, it is often administered to protect the uterine lining if estrogen is also being replaced.

Some women opt for Pellet Therapy, which involves the subcutaneous insertion of long-acting testosterone pellets. This method provides a steady release of hormones over several months, reducing the need for frequent injections. Anastrozole may be included with pellet therapy when appropriate, particularly if there is a concern about excessive estrogen conversion.

The impact of these interventions extends beyond symptom relief. Optimizing sex hormone levels in women can improve lipid profiles, reduce systemic inflammation, and support endothelial function, thereby contributing to a healthier cardiovascular system.

Here is a comparison of common testosterone replacement therapy approaches:

| Therapy Type | Primary Target Audience | Typical Administration | Key Considerations for Cardiovascular Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRT Men | Middle-aged to older men with low testosterone symptoms | Weekly intramuscular injections (Testosterone Cypionate), Gonadorelin, Anastrozole | Improves lipid profiles, reduces visceral fat, enhances insulin sensitivity, supports vascular function. |

| TRT Women | Pre/peri/post-menopausal women with relevant symptoms | Weekly subcutaneous injections (Testosterone Cypionate), Progesterone, Pellet Therapy (optional) | Modulates lipid levels, reduces inflammation, supports endothelial health, potentially improves blood pressure regulation. |

Post-TRT or Fertility-Stimulating Protocol for Men

For men who have discontinued TRT or are actively trying to conceive, a specific protocol aims to restore natural testicular function and fertility. This involves a combination of agents that stimulate endogenous hormone production. The protocol typically includes Gonadorelin, which stimulates LH and FSH release, alongside selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like Tamoxifen and Clomid.

These SERMs block estrogen’s negative feedback on the pituitary, thereby increasing LH and FSH secretion and stimulating testicular testosterone production. Anastrozole may be optionally included to manage estrogen levels during this transition phase.

Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy

Growth hormone (GH) plays a vital role in metabolism, body composition, and tissue repair. As individuals age, natural GH production declines, contributing to changes in body composition, reduced vitality, and slower recovery. Growth hormone peptide therapy aims to stimulate the body’s own GH release, offering benefits for active adults and athletes seeking anti-aging effects, muscle gain, fat loss, and improved sleep quality.

These peptides act on different pathways to increase GH secretion. For example, Sermorelin and Ipamorelin / CJC-1295 are Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) analogs or secretagogues that stimulate the pituitary gland to release GH. Tesamorelin is a GHRH analog specifically approved for reducing abdominal fat.

Hexarelin and MK-677 (Ibutamoren) are GH secretagogues that mimic ghrelin, a hormone that stimulates GH release. By optimizing GH levels, these therapies can indirectly support cardiovascular health through improved body composition, better glucose metabolism, and reduced systemic inflammation.

Other Targeted Peptides

Beyond GH-stimulating peptides, other specialized peptides address specific health concerns, often with systemic benefits that extend to cardiovascular well-being.

- PT-141 (Bremelanotide) ∞ This peptide acts on melanocortin receptors in the brain to improve sexual health and desire. While its primary action is on libido, a healthy sexual function is often indicative of broader vascular health and overall well-being.

- Pentadeca Arginate (PDA) ∞ This peptide is recognized for its roles in tissue repair, healing processes, and modulating inflammation. Chronic inflammation is a significant contributor to cardiovascular disease progression. By supporting tissue repair and reducing inflammation, PDA can indirectly contribute to cardiovascular resilience.

These targeted interventions represent a sophisticated approach to health optimization, recognizing that a balanced internal environment is foundational for long-term cardiovascular resilience.

Academic

The long-term cardiovascular risks associated with unaddressed hormonal imbalances extend beyond simple correlations, reaching into the intricate molecular and cellular mechanisms that govern vascular health. A deep understanding of these pathophysiological pathways reveals why maintaining endocrine equilibrium is not merely beneficial, but essential for cardiovascular longevity. This section explores the complex interplay of biological axes, metabolic pathways, and cellular signaling that underpins these risks, providing a detailed perspective on the clinical implications.

How Do Hormonal Dysregulations Affect Vascular Endothelium?

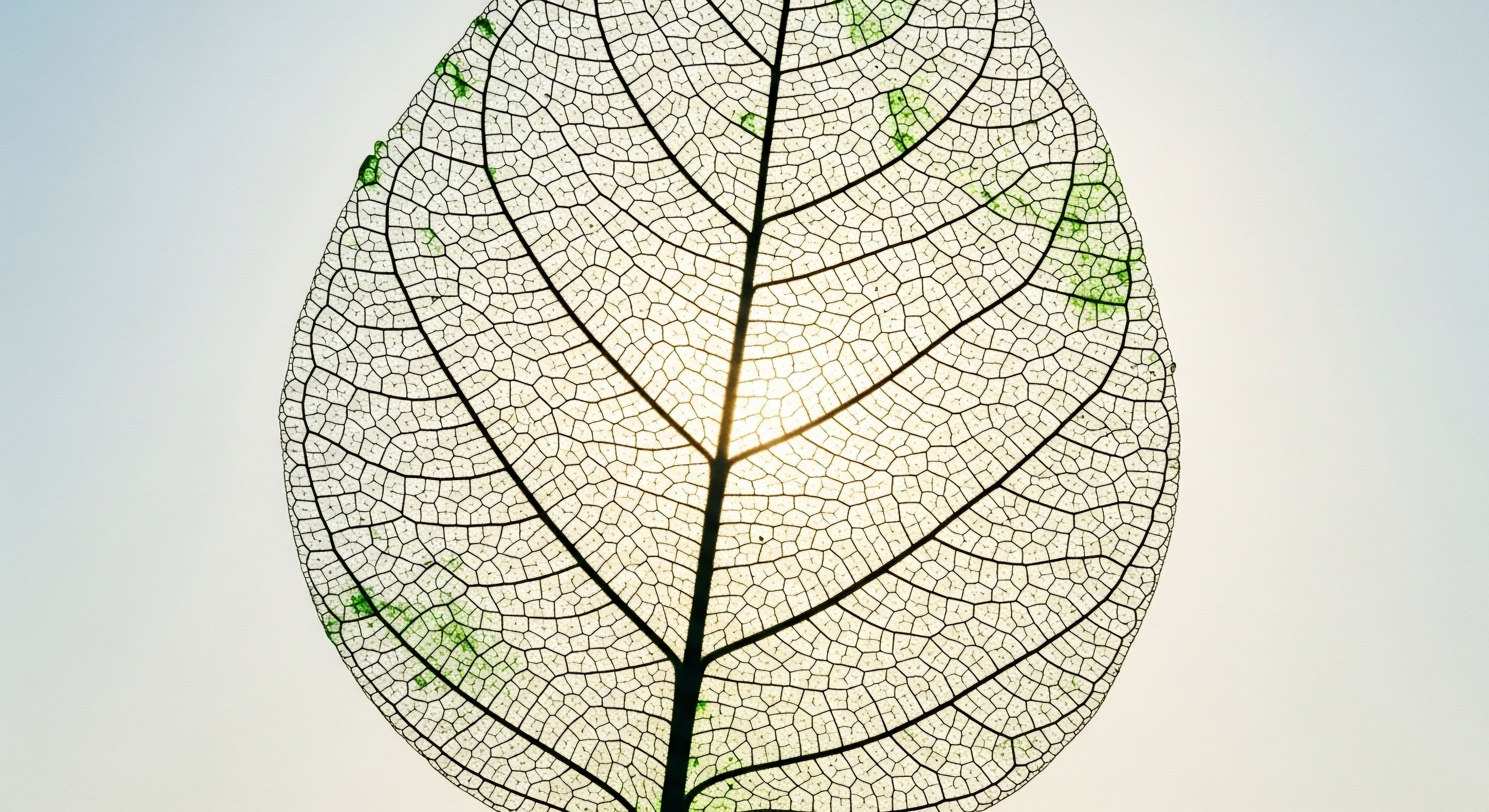

The vascular endothelium, the inner lining of blood vessels, serves as a critical interface between blood and tissue. Its healthy function is paramount for regulating vascular tone, preventing clot formation, and controlling inflammatory responses. Hormonal imbalances directly compromise endothelial integrity and function.

For instance, chronic estrogen deficiency in post-menopausal women leads to reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, a key vasodilator produced by endothelial cells. This reduction in NO contributes to increased vascular stiffness and impaired flow-mediated dilation, both independent predictors of cardiovascular events.

Similarly, low testosterone in men is associated with endothelial dysfunction, characterized by impaired vasodilation and increased expression of adhesion molecules, which promote atherosclerotic plaque formation. Testosterone normally exerts protective effects on the endothelium by promoting NO synthesis and reducing oxidative stress. When these protective effects diminish, the vascular wall becomes more susceptible to damage and inflammation.

Endothelial dysfunction, a silent precursor to cardiovascular disease, is directly influenced by the delicate balance of circulating hormones.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Cardiovascular Health

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis represents a central regulatory system for sex hormone production. Disruptions within this axis, whether at the hypothalamic, pituitary, or gonadal level, can profoundly impact cardiovascular risk. For example, conditions like Kallmann syndrome (a congenital deficiency of GnRH) or acquired hypogonadism (due to aging, obesity, or chronic illness) result in low sex hormone levels. These conditions are consistently linked to adverse cardiovascular profiles, including increased incidence of metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

The HPG axis also interacts extensively with other endocrine axes, such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs stress response, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis, which regulates metabolism. Chronic activation of the HPA axis, leading to sustained cortisol elevation, can suppress the HPG axis, contributing to lower sex hormone levels and exacerbating cardiovascular risk factors. This interconnectedness highlights the systemic nature of hormonal health and its broad implications for cardiovascular well-being.

What Metabolic Pathways Are Impacted by Hormonal Imbalance?

Hormones are master regulators of metabolic pathways, including glucose metabolism, lipid synthesis, and energy expenditure. Imbalances can lead to metabolic dysregulation, a direct pathway to cardiovascular disease.

Insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin, is a common consequence of hormonal imbalances, particularly low testosterone and estrogen deficiency. Insulin resistance leads to elevated blood glucose levels, increased triglyceride synthesis, and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, a protective factor against atherosclerosis. This metabolic shift promotes systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, further damaging the vascular endothelium.

Adipose tissue, once considered merely a storage depot, is now recognized as an active endocrine organ, secreting various adipokines that influence metabolic and cardiovascular health. Hormonal imbalances can alter adipokine secretion profiles. For instance, low testosterone is associated with increased leptin and resistin, and decreased adiponectin, all of which contribute to insulin resistance and inflammation. Similarly, estrogen deficiency can lead to a shift in fat distribution towards visceral adiposity, which is metabolically more active and pro-inflammatory.

The following table summarizes key metabolic impacts of hormonal imbalances:

| Hormonal Imbalance | Affected Metabolic Pathways | Cardiovascular Risk Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Testosterone (Men) | Glucose metabolism, lipid synthesis, body composition, insulin sensitivity | Increased visceral fat, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, higher risk of atherosclerosis. |

| Estrogen Deficiency (Women) | Lipid profiles, glucose regulation, fat distribution, inflammatory markers | Adverse lipid shifts (higher LDL, lower HDL), increased visceral adiposity, impaired endothelial function, systemic inflammation. |

| Chronic Cortisol Elevation | Glucose metabolism, fat storage, inflammatory response | Insulin resistance, central obesity, hypertension, increased systemic inflammation, heightened risk of metabolic syndrome. |

| Thyroid Dysregulation | Basal metabolic rate, lipid metabolism, cardiac contractility | Hyperthyroidism ∞ Tachycardia, arrhythmias, increased cardiac output. Hypothyroidism ∞ Bradycardia, hyperlipidemia, increased vascular resistance. |

How Do Neurotransmitter Functions Relate to Hormonal Imbalances and Cardiovascular Health?

The brain’s neurotransmitter systems are deeply intertwined with endocrine function, and their dysregulation can indirectly affect cardiovascular health. Hormones influence the synthesis, release, and receptor sensitivity of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. For example, sex hormones modulate mood and stress responses through their actions on central nervous system pathways.

Chronic stress, mediated by the HPA axis and its primary hormone, cortisol, leads to sustained activation of the sympathetic nervous system. This results in elevated heart rate, increased blood pressure, and vasoconstriction, placing chronic strain on the cardiovascular system. Hormonal imbalances can exacerbate this stress response. For instance, low testosterone in men and estrogen deficiency in women are linked to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms, which are themselves independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Furthermore, neurotransmitters like dopamine influence reward pathways and appetite regulation. Hormonal imbalances can disrupt these pathways, contributing to unhealthy eating patterns and weight gain, which in turn contribute to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. Understanding these complex, multi-system interactions underscores the necessity of a comprehensive approach to health, where hormonal balance is recognized as a cornerstone of cardiovascular resilience.

References

- Traish, Abdulmaged M. et al. “The dark side of testosterone deficiency ∞ II. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 30, no. 1, 2009, pp. 23-32.

- Rosano, Giuseppe M. C. et al. “Cardiovascular disease and hormone replacement therapy in women.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 46, no. 10, 2005, pp. 1789-1795.

- Chrousos, George P. “Stress and disorders of the stress system.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 7, 2009, pp. 374-381.

- Corona, Giovanni, et al. “Testosterone and cardiovascular risk ∞ a critical appraisal.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 16, no. 3, 2015, pp. 225-241.

- Davis, Susan R. et al. “Testosterone for women ∞ the clinical practice guideline of The Endocrine Society.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 10, 2016, pp. 3653-3668.

- Veldhuis, Johannes D. et al. “Physiological regulation of the human growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) axis ∞ evidence for a GH-IGF-I feedback loop.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 80, no. 11, 1995, pp. 3251-3258.

- Mendelsohn, Michael E. and Richard H. Karas. “The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 340, no. 23, 1999, pp. 1801-1811.

- Jones, T. Hugh. “Testosterone deficiency ∞ a risk factor for cardiovascular disease?” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 20, no. 1, 2009, pp. 16-21.

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 11, 2013, pp. 3559-3571.

- McEwen, Bruce S. “Stress, adaptation, and disease ∞ Allostasis and allostatic overload.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 840, no. 1, 1998, pp. 33-44.

- Reaven, Gerald M. “Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease.” Diabetes, vol. 37, no. 12, 1988, pp. 1595-1607.

- Tchernof, Anne, and Jean-Pierre Després. “Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity ∞ an update.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 80, no. 4, 2000, pp. 1021-1043.

- Kvetnansky, Richard, et al. “Stress-induced changes in catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in the adrenal medulla.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 78, no. 2, 1998, pp. 543-583.

- Pan, An, et al. “Bidirectional association between depression and cardiovascular disease ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.” Circulation, vol. 125, no. 13, 2012, pp. 1620-1629.

Reflection

Understanding the intricate connections between your hormonal landscape and cardiovascular health marks a significant step on your personal wellness path. This knowledge moves beyond simply acknowledging symptoms; it empowers you to comprehend the underlying biological mechanisms at play. Your body possesses an inherent capacity for balance, and recognizing the signals of imbalance is the first act of self-advocacy.

Consider this information not as a definitive endpoint, but as a starting point for deeper introspection. What aspects of your daily experience might be linked to subtle hormonal shifts? How might a more precise understanding of your internal chemistry redefine your approach to long-term health?

The journey toward reclaiming vitality is deeply personal, requiring a thoughtful, informed dialogue with your own biological systems. This ongoing conversation, guided by clinical insight, holds the potential to redefine your health trajectory and secure a more robust future.