Fundamentals

Your body is a meticulously organized system, and the way it receives and processes information is paramount. When we consider hormonal support, particularly estrogen, the method of delivery is as meaningful as the molecule itself. You may be feeling the profound shifts of menopause and seeking to understand how to best support your long-term health, especially your cardiovascular system.

The conversation begins with understanding the journey the hormone takes once it enters your body. This path dictates its effects, its benefits, and its risks.

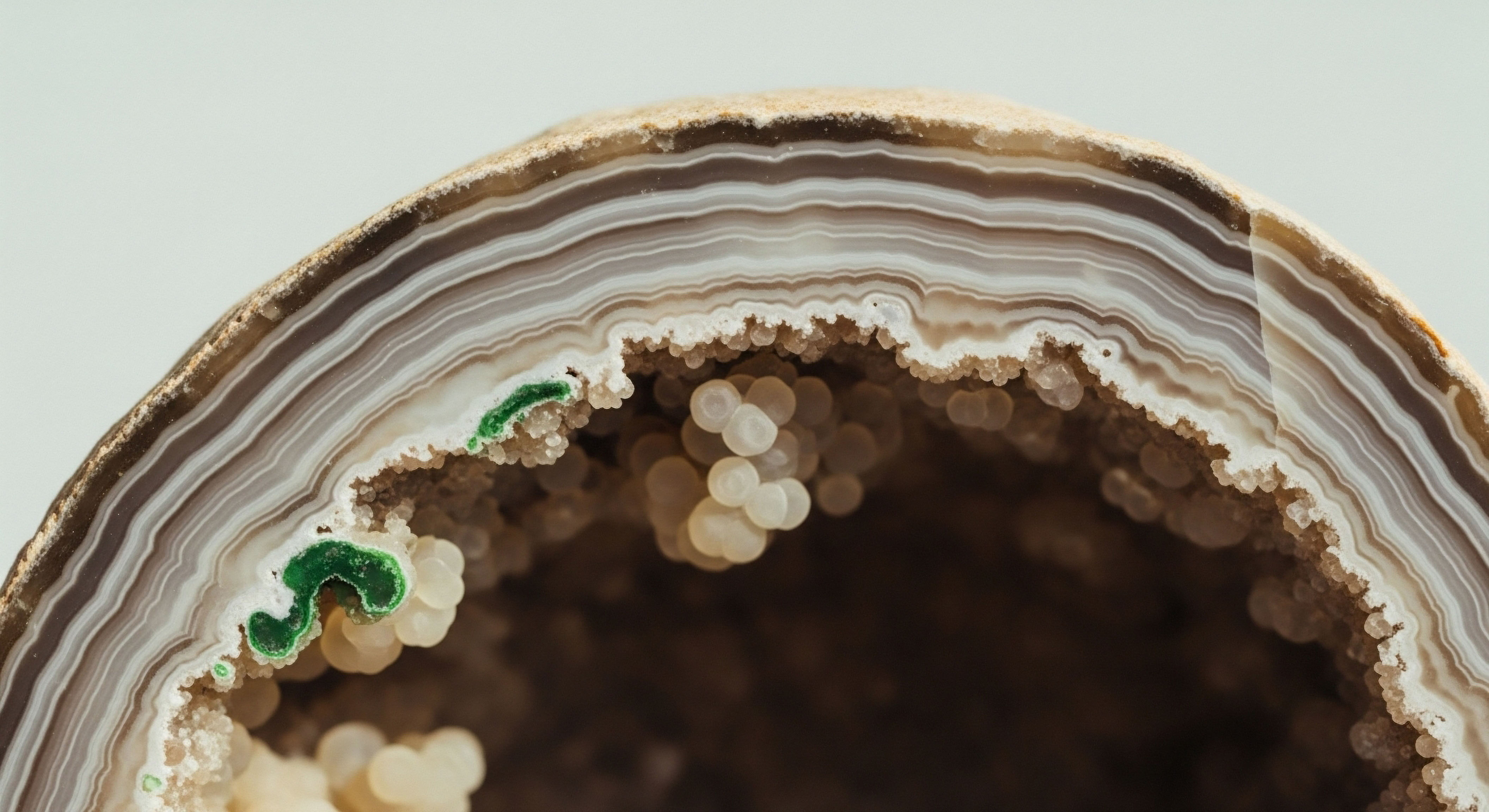

Imagine two different delivery routes for a vital message within a complex communication network. One route sends the message directly to its intended recipients throughout the system. The second route requires the message to first pass through a central processing hub, where it is analyzed, repackaged, and potentially altered before being distributed.

This is the essential distinction between transdermal and oral estrogen administration. Transdermal estrogen, delivered via a patch or gel, is absorbed directly through the skin into the systemic circulation. It reaches the heart, blood vessels, and other tissues in its native form, 17-beta estradiol, mimicking the body’s own natural release from the ovaries.

The route of estrogen administration directly influences its interaction with the liver and subsequent effects on cardiovascular health markers.

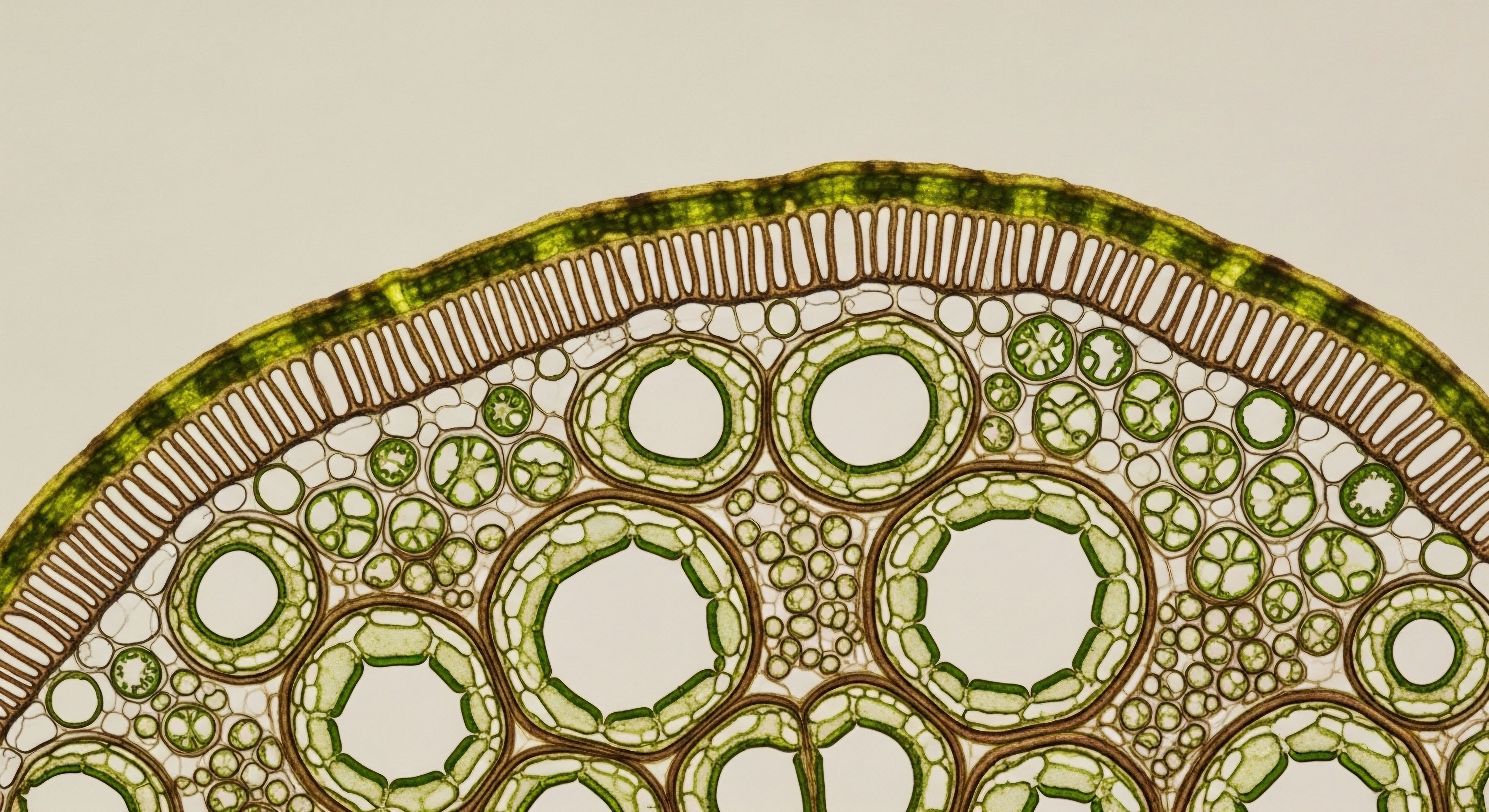

Conversely, oral estrogen must first undergo a “first-pass metabolism” in the liver. When you swallow an estrogen tablet, it is absorbed from the gut and transported directly to the liver. This organ, your body’s primary metabolic clearinghouse, processes the estrogen at a concentration four to five times higher than what your body would naturally experience.

This intense hepatic exposure prompts the liver to produce a cascade of proteins that it would not otherwise make in such quantities. This includes an increase in factors that promote blood clotting, inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP), and triglycerides.

While oral estrogen can also produce some beneficial changes in cholesterol, such as raising HDL and lowering LDL, the concurrent increase in these other factors introduces a layer of complexity to its cardiovascular profile. Understanding this fundamental difference in metabolic pathways is the first step in appreciating why the long-term cardiovascular outcomes of estrogen therapy are so closely tied to the chosen delivery system.

The Direct Path and Its Implications

Choosing a transdermal route is a decision to bypass this aggressive first-pass hepatic effect. By delivering estradiol directly into the bloodstream, the hormone circulates at a steady, physiological level, interacting with receptors throughout the body without first triggering a large-scale metabolic response from the liver.

This avoidance is central to its cardiovascular safety profile. The body’s intricate systems for managing inflammation and coagulation are left undisturbed. This direct-to-circulation method is the primary reason that current clinical thinking and evidence point toward a more favorable long-term cardiovascular outlook with transdermal estrogen. It allows the tissues to receive the benefits of estrogen restoration without the unintended consequences of hepatic overstimulation.

Intermediate

Building upon the foundational knowledge of metabolic pathways, we can now examine the specific clinical data that differentiates the long-term cardiovascular outcomes of transdermal and oral estrogen. The conversation shifts from the theoretical journey of the hormone to the measurable impact on your biology. For women navigating the decisions around hormonal optimization, this evidence provides a clearer picture of the risk-benefit landscape, allowing for a more informed and personalized approach to wellness.

The “timing hypothesis” is a critical concept in this discussion. Extensive research suggests that the cardiovascular effects of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) are highly dependent on when it is initiated relative to the onset of menopause.

Initiating therapy in recently menopausal women (typically defined as under age 60 or within 10 years of the final menstrual period) appears to be associated with either neutral or potentially beneficial cardiovascular effects. The Endocrine Society’s clinical practice guidelines affirm that for most symptomatic women in this window, the benefits of MHT are likely to outweigh the risks.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS), which specifically enrolled healthy, recently menopausal women, provided significant reassurance about the safety of initiating hormone therapy in this group, finding no increase in adverse cardiovascular events with either oral or transdermal estrogen over a four-year period.

Transdermal estrogen is associated with a lower risk of venous thromboembolism compared to oral formulations because it avoids the liver’s first-pass metabolic effect on clotting factors.

The most pronounced and consistently observed difference between the two delivery routes lies in the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), or blood clots. Meta-analyses and large observational studies have repeatedly shown that oral estrogen increases the risk of VTE, while transdermal estrogen at standard doses does not appear to share this risk.

This distinction is a direct consequence of the first-pass effect, where oral estrogen stimulates the liver to produce clotting proteins. For this reason, clinical guidelines often recommend transdermal estrogen as the preferred option for women who have underlying risk factors for VTE.

A Comparative Look at Cardiometabolic Markers

To fully appreciate the distinct profiles of oral and transdermal estrogen, it is useful to compare their effects on a range of cardiovascular and metabolic markers. The following table synthesizes data from multiple studies and clinical observations.

| Cardiovascular Marker | Oral Estrogen Effects | Transdermal Estrogen Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Risk |

Increased risk due to hepatic production of clotting factors. |

Neutral effect; no significant increase in risk at standard doses. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

Significantly increases this inflammatory marker. |

Neutral effect; does not increase inflammatory markers. |

| Triglycerides |

Significantly increases levels. |

Neutral or may cause a slight reduction. |

| LDL Cholesterol (“Bad” Cholesterol) |

Favorable reduction. |

Minimal effect. |

| HDL Cholesterol (“Good” Cholesterol) |

Favorable increase. |

Minimal effect. |

| Blood Pressure |

Variable effects, may slightly increase. |

Generally neutral or may slightly decrease. |

What Is the Role of Progesterone in Cardiovascular Health?

For women with a uterus, hormonal therapy requires the inclusion of a progestogen to protect the endometrium. It is important to recognize that the type of progestogen can also influence cardiovascular outcomes. Some synthetic progestins may partially counteract the beneficial lipid effects of estrogen.

Micronized progesterone, which is structurally identical to the body’s own progesterone, appears to have a more neutral effect on metabolic and cardiovascular markers and is often preferred in modern hormonal optimization protocols. Therefore, a truly personalized assessment considers the type and route of both the estrogen and the progestogen component.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the long-term cardiovascular outcomes with transdermal estrogen requires a deep appreciation of the methodologies and populations of key clinical trials, as well as the specific biomolecular mechanisms that underpin the observed clinical differences.

The scientific narrative has evolved significantly from the initial findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which primarily studied an older population using oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) and medroxyprogesterone acetate. The subsequent research, including the KEEPS trial and numerous mechanistic studies, has provided a more refined, systems-based understanding that prioritizes the route of administration as a primary determinant of cardiovascular safety.

The core mechanistic divergence is the hepatic first-pass metabolism unique to oral estrogens. This is not a subtle biochemical distinction; it is a profound physiological event that reshapes the cardiometabolic milieu. Transdermal administration of 17-beta estradiol delivers the hormone directly to the systemic circulation, avoiding this hepatic insult.

Oral administration, in contrast, exposes hepatocytes to supraphysiologic estrogen levels, inducing the synthesis of a wide array of proteins. This includes not just beneficial lipoproteins but also procoagulant factors (like prothrombin fragments 1+2) and acute-phase inflammatory reactants such as C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A.

Transdermal estrogen does not provoke these adverse changes. This explains the consistent clinical finding of a higher VTE risk with oral therapy and a neutral VTE risk with transdermal therapy. From a systems-biology perspective, the transdermal route maintains homeostasis, while the oral route perturbs it.

Interpreting the Evidence from Clinical Trials

The KEEPS trial was instrumental in shifting the clinical paradigm. By focusing exclusively on healthy women within three years of menopause, it tested the “timing hypothesis” directly. Its primary endpoint, the rate of change in carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), showed no significant difference between placebo, oral CEE, or transdermal estradiol over four years.

While on the surface this suggests a lack of cardiovascular benefit, a deeper interpretation is required. CIMT is a surrogate marker for atherosclerosis, and its progression in a healthy, young population over a relatively short four-year period is expected to be minimal. The trial’s true value was in its demonstration of safety. In this low-risk population, neither hormone formulation precipitated adverse cardiovascular events, a stark contrast to the findings in the older WHI cohort.

Mechanistic studies show that transdermal estrogen avoids the adverse hepatic induction of procoagulant and inflammatory proteins seen with oral formulations.

A 14-year follow-up of the KEEPS participants found no lasting cardiovascular or metabolic benefits or harms from the original four-year intervention. This finding underscores that a short course of hormone therapy early in menopause is unlikely to impart lifelong cardiovascular protection, but it also confirms its long-term safety.

The primary long-term cardiovascular “outcome” with transdermal estrogen, therefore, is best framed as an outcome of non-harm. It effectively manages menopausal symptoms without introducing the risks of a prothrombotic and proinflammatory state that are inherent to the oral route.

| Trial / Study Type | Population Characteristics | Key Cardiovascular Findings Related to Estrogen Route |

|---|---|---|

| WHI (Women’s Health Initiative) |

Older, postmenopausal women (average age 63), many >10 years past menopause. Primarily used oral CEE. |

Showed increased risk of stroke and VTE with oral therapy, leading to the initial negative perception of MHT. |

| KEEPS (Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study) |

Younger, healthy, recently menopausal women (within 3 years of menopause). Compared oral CEE, transdermal estradiol, and placebo. |

Found no significant effect on CIMT progression but demonstrated the cardiovascular safety of both routes when initiated early. |

| Observational Studies & Meta-Analyses |

Large, diverse populations of women using various MHT formulations in real-world settings. |

Consistently demonstrate a lower risk of VTE with transdermal estrogen compared to oral estrogen. Some studies suggest a lower risk of stroke and MI with transdermal use as well. |

How Does Transdermal Estrogen Affect Arterial Health Long Term?

While the risk of VTE is clearly lower with transdermal estrogen, the effects on arterial disease (myocardial infarction and stroke) are more nuanced. Some large-scale observational data have suggested a borderline reduction in myocardial infarction risk with transdermal estradiol.

The avoidance of inflammation (no CRP increase) and the potential for favorable effects on vascular function provide a plausible biological mechanism for this benefit. However, major clinical practice guidelines, including those from The Endocrine Society, maintain that MHT, regardless of the route, should not be prescribed for the sole purpose of primary or secondary cardiovascular disease prevention.

The long-term strategy with transdermal estrogen is to provide the systemic benefits of hormone restoration while actively minimizing the known cardiovascular risks associated with the oral route, creating a superior safety profile for long-term use.

References

- Stuenkel, Cynthia A. et al. “Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, 2015, pp. 3975 ∞ 4011.

- Harman, S. Mitchell, et al. “The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) ∞ what have we learned?.” Menopause, vol. 28, no. 9, 2021, pp. 1071-1085.

- Kantarci, Kejal, et al. “Cardiometabolic outcomes in Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study continuation ∞ 14-year follow-up of a hormone therapy trial.” Menopause, vol. 31, no. 1, 2024, pp. 28-36.

- Lobo, Rogerio A. “Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Cardiovascular Disease ∞ The Role of Formulation, Dose, and Route of Delivery.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 102, no. 9, 2017, pp. 3185 ∞ 3194.

- Mohan, Madhu, and Wael A. Jaber. “Effects of transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on cardiovascular risk factors.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, vol. 73, no. 8, 2006, pp. 713-716.

- Boardman, Holly M. et al. “Oral vs Transdermal Estrogen Therapy and Vascular Events ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 5, 2015, pp. 1927 ∞ 1936.

- Vinogradova, Yana, et al. “Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism ∞ nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases.” BMJ, vol. 364, 2019, k4810.

- Miller, Virginia M. et al. “Lessons from KEEPS ∞ the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study.” Climacteric, vol. 22, no. 5, 2019, pp. 472-478.

Reflection

The journey through the clinical science of hormonal health reveals a clear principle ∞ the method of delivery is integral to the outcome. You have seen how the simple choice of administration route ∞ skin versus tablet ∞ can fundamentally alter the body’s response, particularly within the cardiovascular system.

This knowledge moves the conversation beyond a simple question of whether to use estrogen to a more refined inquiry of how to best align a therapy with your unique physiology and long-term wellness goals. Your individual health history, your metabolic profile, and your personal priorities all form the context for this decision.

The information presented here is a map, designed to help you understand the terrain. The next step is a personalized dialogue with a trusted clinical guide to chart your specific path forward, ensuring that every choice is made with clarity, confidence, and a deep respect for your body’s intricate design.

Glossary

transdermal estrogen

oral estrogen

first-pass metabolism

c-reactive protein

long-term cardiovascular outcomes

with transdermal estrogen

cardiovascular safety

cardiovascular outcomes

menopausal hormone therapy

timing hypothesis

recently menopausal women

kronos early estrogen prevention study

hormone therapy

venous thromboembolism

micronized progesterone

keeps trial