Fundamentals

You may feel a persistent sense of fatigue that sleep does not seem to correct. Perhaps you notice a subtle but definite decline in your physical strength, an unwelcome shift in your body composition, or a quiet fading of the inner vitality that once defined your sense of self.

When you seek answers, these experiences are sometimes attributed to the inevitable process of aging or the hormonal shifts of menopause. This explanation, while partially true, is incomplete. It fails to capture the intricate biological narrative unfolding within your body. Your physiology is a responsive, dynamic system, and these symptoms are signals, valuable pieces of data from your body’s internal communication network. Understanding this network is the first step toward reclaiming your functional well-being.

At the center of this network are hormones, the chemical messengers that regulate nearly every process in your body. Testosterone is one of these critical messengers in women. Its role is often narrowly associated with libido, yet its physiological responsibilities are far more extensive.

Testosterone contributes to the maintenance of lean muscle mass, the preservation of bone density, and the regulation of metabolic function. It is a key component in the complex formula that supports your energy, mood, and overall resilience. When its levels decline with age, the effects are felt systemically, touching multiple aspects of your health in ways that are interconnected and deeply personal.

The Cardiovascular System as a Hormonal Recipient

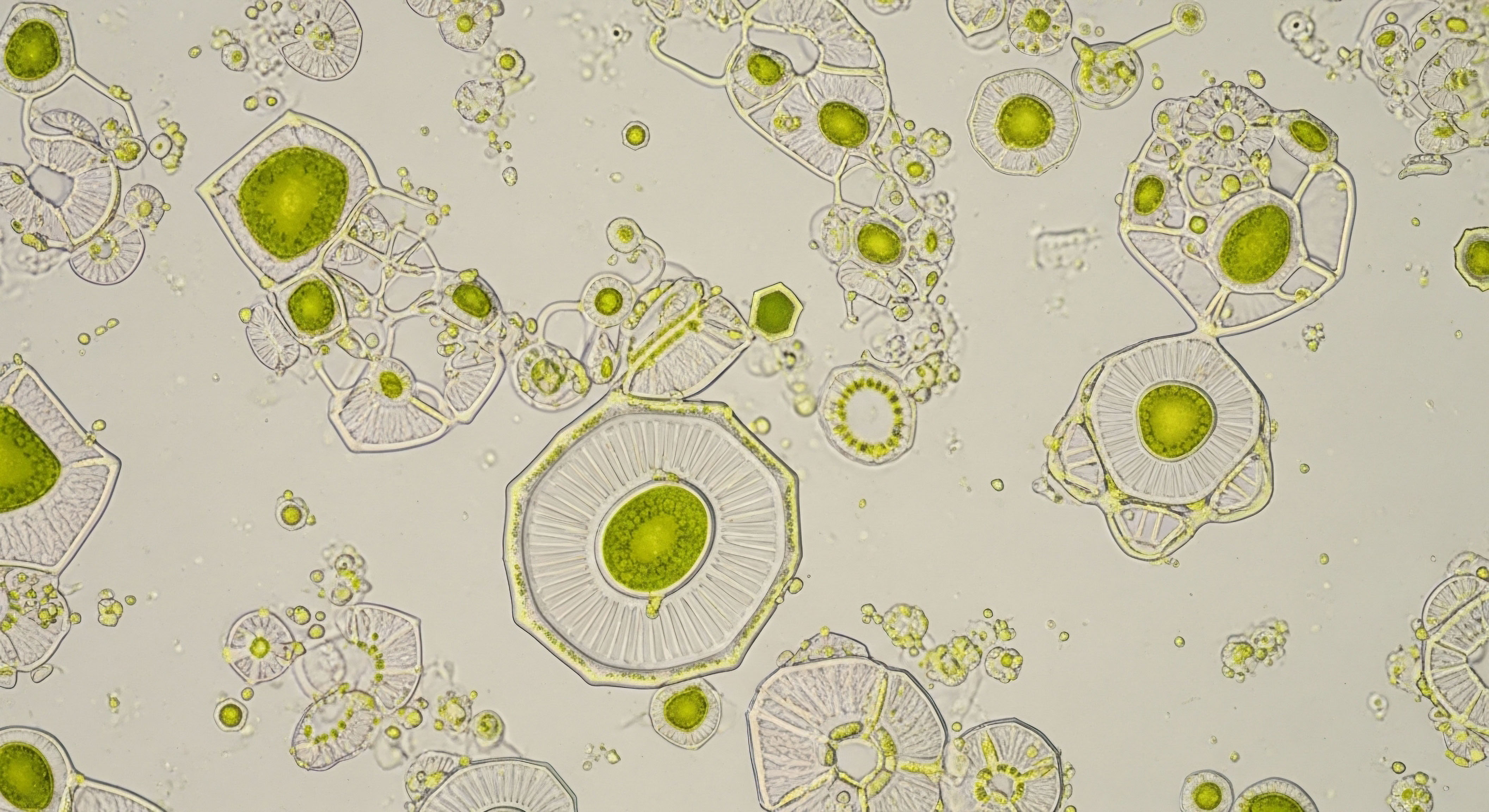

The heart, arteries, and veins that constitute your cardiovascular system are not passive tubes and pumps. They are highly active, hormonally responsive tissues. The cells that line your blood vessels, known as the endothelium, are equipped with receptors that bind to hormones, including testosterone.

This means that your cardiovascular function is in constant dialogue with your endocrine system. The hormonal fluctuations that characterize perimenopause and postmenopause represent a significant change in this dialogue. The decline in both estrogen and testosterone alters the signals being sent to your vascular tissues, influencing their ability to function optimally.

A woman’s cardiovascular system is deeply intertwined with her endocrine health, responding directly to the body’s hormonal signals.

This brings us to a foundational question that moves beyond a simple assessment of risk. When we consider supplementing with testosterone, we are asking how reintroducing a specific, familiar signal at a physiological level influences the cardiovascular system over the long term. It is a question about restoration and biological communication.

The goal of such a protocol is to restore a key element of the body’s messaging service, aiming to support the function of tissues that depend on its presence. The investigation into its long-term cardiovascular outcomes is therefore an exploration of how this restored communication affects the health and resilience of the heart and vasculature over time.

Why Is Endogenous Testosterone Important for Female Health?

Endogenous testosterone, the testosterone your body produces naturally, serves as a cornerstone for female physiological architecture. From a biological standpoint, its presence is essential for building and maintaining metabolically active tissue. Muscle is a primary example. Testosterone supports protein synthesis, the process by which muscle fibers are repaired and built.

Stronger muscle mass contributes to a higher resting metabolic rate, improved insulin sensitivity, and greater physical stability. Similarly, it plays a vital part in bone health by stimulating the activity of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for forming new bone tissue. This helps to counteract the natural bone loss that accelerates during menopause.

The hormone’s influence extends into the central nervous system, where it modulates neurotransmitter activity that affects mood, cognitive clarity, and assertiveness. A decline in testosterone can correspond with feelings of hesitation, mental fog, or a diminished sense of motivation. By understanding testosterone’s broad spectrum of action, we can begin to appreciate that its decline is not an isolated event.

It is a systemic shift that can manifest as a collection of symptoms that together diminish one’s quality of life. Recognizing this interconnectedness is the basis for a more comprehensive approach to female hormonal health.

Intermediate

To comprehend the long-term cardiovascular outcomes of testosterone therapy in women, we must examine the specific biological mechanisms through which this hormone interacts with the vascular system. The conversation moves from the general concept of hormonal influence to the precise actions testosterone exerts at a cellular and systemic level.

These mechanisms provide the scientific rationale for why physiological testosterone administration is being studied for its potential to support, rather than compromise, cardiovascular health. The effects are multifaceted, involving blood vessel function, inflammatory processes, and metabolic regulation.

Mechanisms of Testosterone in the Cardiovascular System

Testosterone’s influence on cardiovascular health is not a single action but a cascade of interrelated effects. One of the most significant is its impact on endothelial function. The endothelium is the inner lining of your blood vessels, and its health is a primary determinant of overall cardiovascular wellness.

A healthy endothelium produces nitric oxide, a molecule that signals the surrounding smooth muscle of the arteries to relax. This process, called vasodilation, widens the blood vessels, which lowers blood pressure and improves blood flow. Evidence suggests that testosterone can support nitric oxide production, thereby promoting healthy vascular tone and responsiveness. This action helps maintain the flexibility and resilience of the arteries.

Impact on Inflammation and Metabolic Markers

Chronic inflammation is a well-established driver of atherosclerosis, the process of plaque buildup in the arteries. Certain inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), are used to assess cardiovascular risk. Studies have explored the relationship between testosterone therapy and these markers. Some research indicates that testosterone may have a modulatory effect on inflammation.

For instance, while estrogen therapy can sometimes lead to an increase in CRP levels, concurrent administration of testosterone appears to suppress this effect, suggesting a potential anti-inflammatory or balancing action within the vascular system.

The hormone’s metabolic influence is also a key piece of the puzzle. Testosterone has a known effect on body composition, favoring the development of lean muscle mass over adipose (fat) tissue. Since muscle tissue is more metabolically active and responsive to insulin than fat tissue, this shift can lead to improved insulin sensitivity.

Better insulin sensitivity means the body can manage blood sugar more effectively, reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, both of which are major contributors to cardiovascular disease. By improving these fundamental metabolic parameters, testosterone therapy addresses some of the root causes of cardiovascular strain.

Physiological testosterone therapy may support cardiovascular health by improving blood vessel function, modulating inflammation, and enhancing metabolic efficiency.

Clinical Protocols and the Importance of Physiological Dosing

The method of administration and the dosage of testosterone are critical factors that determine its physiological effects and safety profile. The objective of hormonal optimization protocols is to restore serum testosterone levels to the upper end of the normal physiological range for a healthy young woman. This is distinctly different from using supraphysiological doses, which can produce unwanted androgenic side effects and may negatively affect cardiovascular markers. Common administration methods include subcutaneous injections, transdermal patches, and subcutaneous pellets.

- Subcutaneous Injections ∞ Weekly or twice-weekly subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate (e.g. 10 ∞ 20 units, or 0.1 ∞ 0.2ml) allow for stable and predictable serum levels. This method avoids the daily fluctuations of gels and the peaks and troughs associated with older intramuscular injection protocols.

- Pellet Therapy ∞ Subcutaneous pellets are implanted under the skin and release testosterone slowly over a period of three to four months. This method provides consistent hormone levels without the need for frequent administration. Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, may be used concurrently if needed to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen.

- Transdermal Patches ∞ Patches applied to the skin deliver testosterone directly into the bloodstream. This method has been studied in several large clinical trials and has shown efficacy for specific indications, with a good safety profile regarding cardiovascular markers like lipids and CRP.

The choice of protocol is based on individual patient factors, including lifestyle, preference, and metabolic characteristics. Close monitoring of blood levels and clinical symptoms is essential to ensure the dose is optimized for benefit while minimizing any potential for adverse effects. The entire clinical approach is built on the principle of “physiological restoration,” using the lowest effective dose to achieve the desired clinical outcomes.

Reviewing the Evidence on Lipid Profiles

The effect of testosterone therapy on lipid profiles (cholesterol and triglycerides) has been a significant area of study. The concern has historically been that androgens could adversely affect lipids, specifically by lowering high-density lipoprotein (HDL, or “good” cholesterol) and raising low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or “bad” cholesterol).

However, research into modern, physiological dosing protocols in women presents a more complex picture. Many studies have found that when testosterone is administered in doses that maintain levels within the female physiological range, there are no clinically significant adverse effects on lipid profiles. Some studies even report modest improvements.

The table below summarizes the general findings from studies using different administration methods on key cardiovascular markers. It is important to recognize that results can vary based on the population studied, the dosage used, and the duration of the trial.

| Administration Method | Effect on HDL Cholesterol | Effect on LDL Cholesterol | Effect on Triglycerides | Effect on C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transdermal Patch | Generally neutral or minimal change. | Generally neutral or minimal change. | Generally neutral. | No significant increase; may blunt estrogen-induced increase. |

| Subcutaneous Pellets | Variable; some studies show a slight decrease with higher doses. | Generally neutral. | Generally neutral. | Generally neutral. |

| Subcutaneous Injections | Generally neutral at physiological doses. | Generally neutral at physiological doses. | Generally neutral. | Data is less extensive but points toward neutrality. |

These findings underscore the importance of the therapeutic philosophy. The goal is balance and restoration, which appears to avoid the negative lipid effects associated with the high-dose androgen use seen in other contexts. The lack of long-term, large-scale randomized controlled trials remains a limitation in the field, making ongoing data collection and analysis a priority. Short-term and medium-term data, however, are reassuring and point toward cardiovascular neutrality or potential benefit when therapy is properly managed.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of testosterone’s long-term cardiovascular outcomes in women requires a deep exploration of the intricate biological crosstalk between sex hormones and the vascular endothelium. The endothelium is a critical regulator of vascular homeostasis. Its dysfunction is a primary event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.

Testosterone, along with its powerful metabolite estradiol, exerts profound and complex effects on endothelial cells through both genomic and non-genomic pathways. Understanding this interplay at a molecular level is essential to building a coherent model of the hormone’s long-term vascular impact.

The Endothelium as a Dynamic Hormonal Sensor

The vascular endothelium is a single layer of cells lining all blood vessels, forming a dynamic interface between the blood and the vessel wall. It actively controls vascular tone, inflammation, coagulation, and cell proliferation. This tissue is richly populated with androgen receptors (AR) and estrogen receptors (ER), making it exquisitely sensitive to circulating sex steroids.

The binding of testosterone to AR or estradiol to ER initiates signaling cascades that modulate the expression of key genes involved in vascular function. One of the most important of these is endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for producing the potent vasodilator nitric oxide (NO).

Testosterone’s effect on eNOS is multifaceted. Through genomic mechanisms, activation of the AR can lead to increased transcription of the eNOS gene, resulting in a greater cellular capacity to produce NO over time. This supports long-term vascular health by promoting a state of vasodilation. Testosterone also demonstrates rapid, non-genomic effects.

It can trigger intracellular calcium mobilization and activate protein kinase pathways that phosphorylate and activate existing eNOS enzymes within seconds to minutes. This provides a mechanism for immediate adjustments in vascular tone in response to hormonal signals. This dual action, both immediate and sustained, underscores the hormone’s integral role in vascular regulation.

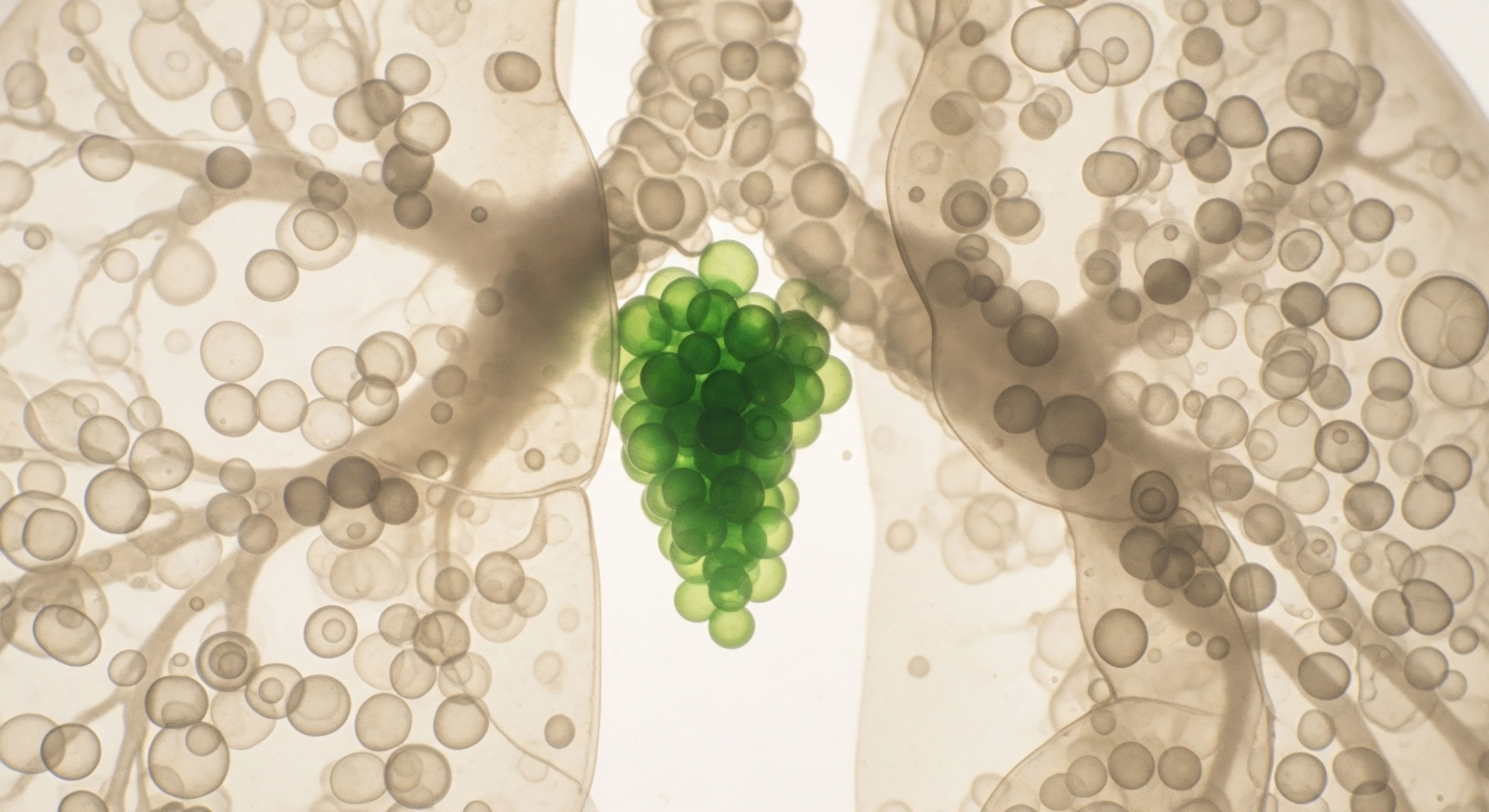

Aromatization the Critical Conversion to Estradiol

The biological activity of testosterone in women cannot be understood without considering its conversion to estradiol by the enzyme aromatase. Aromatase is present in various tissues, including adipose tissue, bone, brain, and the vascular endothelium itself. This local production of estradiol from a testosterone precursor is a pivotal mechanism. It means that some of the beneficial vascular effects observed with testosterone administration are, in fact, mediated by estradiol acting on estrogen receptors.

Estradiol is known to be a powerful vasculoprotective hormone. It strongly upregulates eNOS expression and activity, promotes endothelial cell survival and repair, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Therefore, testosterone serves as a prohormone, providing the substrate for local estradiol synthesis within the very tissues that need its protective effects.

This creates a beautifully integrated system where testosterone provides its own direct androgenic benefits while also ensuring a localized supply of estradiol to support vascular health. The clinical implication is that the net cardiovascular effect of testosterone therapy is a composite of the actions of both testosterone and its estrogenic metabolite. This balance is a key area of ongoing research.

The cardiovascular effects of testosterone are mediated through a complex interplay of direct androgen receptor activation and its local conversion to protective estradiol within vascular tissue.

This systems-biology perspective challenges a simplistic view of testosterone as a singular agent. Its effects are context-dependent, influenced by the local enzymatic machinery of the target tissue and the relative expression of androgen and estrogen receptors. The therapeutic goal, therefore, is to restore a hormonal milieu that allows for these integrated, physiological processes to function optimally.

What Regulatory Hurdles Exist for Global Therapy Approval?

The path to global regulatory approval for any therapeutic agent, including testosterone for women, is predicated on the submission of extensive and robust clinical trial data. Regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) require large-scale, long-term, randomized, placebo-controlled trials to definitively establish both efficacy and safety for a specific indication.

The primary hurdle for testosterone therapy in women has been the significant financial investment required to conduct such trials. The primary indication studied has been Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD), and while efficacy has been demonstrated, concerns about long-term safety, particularly regarding cardiovascular and breast outcomes, have remained a focus for regulators.

A regulatory body would require data that specifically addresses these long-term outcomes over many years in a large and diverse population of women. This includes detailed tracking of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), such as myocardial infarction and stroke, as well as changes in surrogate markers like carotid intima-media thickness, coronary artery calcium scores, and comprehensive lipid and inflammatory panels.

Assembling such a data package is a monumental undertaking, and the commercial incentive has been insufficient for pharmaceutical companies to pursue it aggressively to date. This has led to the current situation where use is widespread, often off-label, while definitive long-term data remains elusive.

Deep Analysis of Clinical Trial Data

While a definitive, large-scale, long-term trial is lacking, a body of smaller, high-quality studies provides significant insight. Meta-analyses of these randomized controlled trials have been conducted to pool the available data and strengthen the conclusions.

A key meta-analysis published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology synthesized data from numerous trials and found no statistically significant increase in adverse cardiovascular events in women treated with testosterone compared to placebo over the duration of the studies included. These trials, while not designed for long-term cardiovascular outcomes as a primary endpoint, provide the best available evidence to date.

The table below details a selection of influential studies to illustrate the nature of the available evidence. It highlights the focus on surrogate markers and the relatively short duration of most investigations.

| Study/Trial | Population | Testosterone Formulation | Duration | Key Cardiovascular Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis et al. (2006) | Surgically menopausal women | Transdermal Patch | 52 weeks | No adverse effects on lipid profile, fasting glucose, or blood pressure compared to placebo. |

| Dobs et al. (2002) | Postmenopausal women | Oral Esterified Androgens | 2 years | Showed potential adverse effects on atherosclerosis markers, but used a high dose and an oral formulation not typically recommended. |

| Worboys et al. (2001) | Postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease | Sublingual Testosterone | Acute Dosing | Demonstrated improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation, suggesting a direct beneficial effect on blood vessel function. |

| Kocoska-Maras et al. (2011) | Postmenopausal women | Transdermal Testosterone Gel | 24 weeks | Found that testosterone suppressed the increase in high-sensitivity CRP induced by oral estrogen. |

The data from these and other studies collectively suggest that physiological testosterone therapy in women is unlikely to pose a significant cardiovascular risk in the short to medium term and may offer benefits related to vasodilation, inflammation, and body composition. The Dobs et al.

study is an important outlier that highlights the critical importance of dose and formulation; high-dose oral androgens behave differently from physiological transdermal or injectable preparations. The primary, unresolved question remains the extrapolation of these findings over a period of decades, a question that can only be answered by continued research and prospective data collection through registries and dedicated long-term trials.

References

- Davis, S. R. et al. “Efficacy and safety of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women ∞ a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.” Menopause, vol. 13, no. 3, 2006, pp. 387-96.

- Islam, R. M. et al. “Effects of testosterone therapy for women ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol.” Systematic Reviews, vol. 8, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1-5.

- Studd, J. W. W. and M. H. Thom. “Hormonal profiles in postmenopausal women after therapy with subcutaneous implants.” BJOG ∞ An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 88, no. 4, 1981, pp. 426-33.

- Davis, S. R. et al. “Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 359, no. 19, 2008, pp. 2005-17.

- Glaser, R. and C. Dimitrakakis. “Testosterone pellet implants and their use in women.” Maturitas, vol. 74, no. 3, 2013, pp. 220-225.

- Achilli, C. et al. “Effects of testosterone on cardiovascular risk factors in the menopause ∞ a review.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017, pp. 152-161.

- Reckelhoff, J. F. et al. “Testosterone supplementation in aging men and women ∞ possible impact on cardiovascular-renal disease.” American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, vol. 289, no. 5, 2005, F941-F948.

- Davis, S. R. and S. Wahlin-Jacobsen. “Testosterone in women ∞ the clinical significance.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, vol. 3, no. 12, 2015, pp. 980-92.

- Traish, A. M. et al. “The dark side of testosterone deficiency ∞ III. Cardiovascular disease.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 6, no. 10, 2009, pp. 2681-99.

- Rosano, G. M. C. et al. “Testosterone in women with heart failure ∞ a pilot study.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 47, no. 8S, 2006, p. 60A.

Reflection

Mapping Your Own Biological Narrative

The information presented here provides a framework for understanding the complex relationship between testosterone and cardiovascular health in women. It is a map of the known territory, drawn from scientific inquiry and clinical observation. Your own health, however, is a unique landscape.

The symptoms you experience, the patterns in your energy, and the story of your physical well-being are all part of a personal, biological narrative. The purpose of this knowledge is to equip you with a better understanding of the language your body is speaking.

Consider the data points of your own life. How has your sense of vitality changed over time? What connections do you perceive between your hormonal life and your physical and emotional state? Viewing your health journey through this lens transforms you from a passive recipient of symptoms into an active observer of your own physiology.

This shift in perspective is the foundation of proactive wellness. The path forward involves a collaborative partnership with a clinician who can help you interpret your unique narrative, using advanced diagnostics and a deep understanding of endocrine science to co-author the next chapter of your health story, one grounded in vitality and optimal function.