Fundamentals

The experience of perimenopause is deeply personal, a time of profound biological shifts that can leave you feeling untethered from the person you once knew. You might notice changes in your energy, your sleep, your mood, and even your sense of self.

These are not just fleeting feelings; they are the outward expression of a complex internal recalibration of your endocrine system. Understanding this process is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. Your body is not failing you. It is transitioning. And within this transition lies an opportunity to proactively support your long-term health, particularly the health of your cardiovascular system.

Estrogen, a hormone often associated primarily with reproduction, plays a far more expansive role in your body. It is a powerful signaling molecule that communicates with cells in your brain, bones, skin, and, critically, your entire cardiovascular system. Think of estrogen as a master conductor of a complex orchestra, ensuring that various sections of your biological symphony play in harmony.

It helps to maintain the flexibility and health of your blood vessels, regulates cholesterol levels, and manages inflammation. During perimenopause, the levels of estrogen begin to fluctuate and decline, and this can disrupt the harmony of your cardiovascular system.

The decline of estrogen during perimenopause is a pivotal event that directly impacts the health and function of your cardiovascular system.

The Heart’s Connection to Hormonal Balance

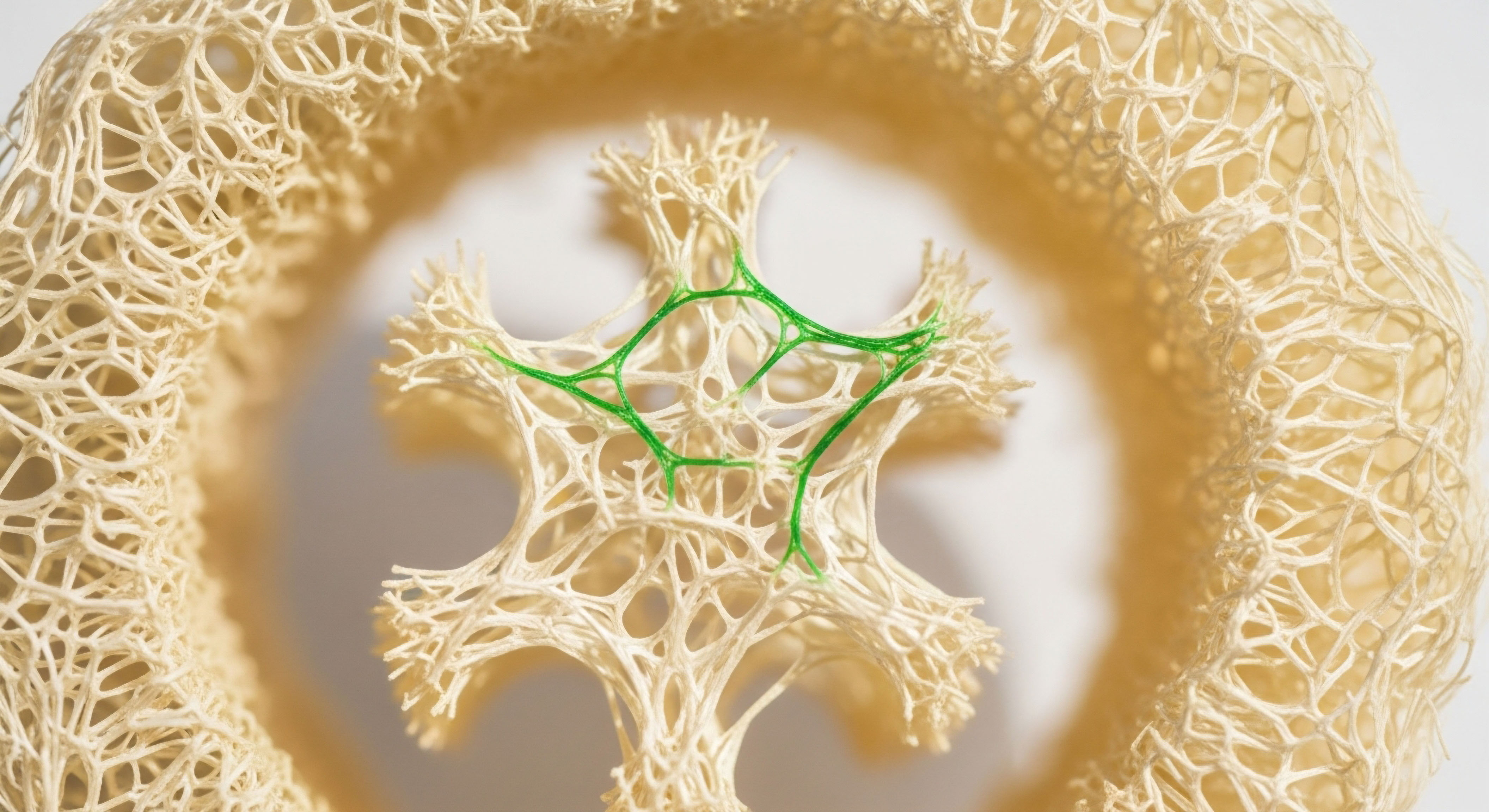

Your heart and blood vessels have a rich network of estrogen receptors. When estrogen binds to these receptors, it sets off a cascade of beneficial effects. For instance, it promotes the production of nitric oxide, a molecule that helps to relax and widen your blood vessels, ensuring smooth blood flow and healthy blood pressure.

Estrogen also has a favorable effect on your lipid profile, helping to lower LDL (low-density lipoprotein), often referred to as “bad” cholesterol, and increase HDL (high-density lipoprotein), or “good” cholesterol. This hormonal support is a key reason why premenopausal women generally have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease compared to men of the same age.

As perimenopause progresses and estrogen levels fall, this protective shield begins to weaken. Your blood vessels may become stiffer, your blood pressure might creep up, and your cholesterol profile can shift in an unfavorable direction. These changes are not happening in isolation.

They are part of a systemic shift that can also affect your metabolism, leading to changes in weight distribution, particularly an increase in visceral fat around your abdomen. This type of fat is metabolically active and can further contribute to inflammation and insulin resistance, both of which are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

What Is the Significance of Early Intervention?

The concept of timing is paramount when considering hormonal support during perimenopause. The idea of initiating estrogen therapy early in this transition is grounded in the principle of preserving the health of your cardiovascular system before significant changes have occurred. This approach is often referred to as the timing hypothesis.

It suggests that there is a “window of opportunity” during perimenopause and early postmenopause when your blood vessels are still healthy and responsive to the beneficial effects of estrogen. By providing estrogen during this critical period, it is possible to maintain the cardiovascular benefits you experienced during your premenopausal years.

This is a proactive strategy. It is about anticipating the biological changes of menopause and taking steps to mitigate their long-term consequences. The goal is to support your body’s natural processes and maintain your health at a cellular level.

Understanding the connection between your hormones and your heart is the foundation for making informed decisions about your health journey. It empowers you to have meaningful conversations with your healthcare provider about personalized strategies that can help you navigate perimenopause with confidence and vitality.

Intermediate

The conversation around menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) has evolved significantly over the past two decades. The initial confusion and concern that arose from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials have given way to a more nuanced understanding of the role of estrogen in women’s health.

The key to this new perspective lies in the timing hypothesis, a concept that has reshaped the clinical approach to MHT and its cardiovascular implications. This hypothesis is not just a theory; it is supported by a growing body of evidence from re-analyzed clinical trials and observational studies.

The timing hypothesis posits that the cardiovascular effects of estrogen therapy are critically dependent on when it is initiated in relation to the onset of menopause. When started in younger, recently menopausal women (typically under the age of 60 and within 10 years of their final menstrual period), estrogen therapy appears to have a protective effect on the heart and blood vessels.

In contrast, initiating therapy in older women who are many years past menopause and may have already developed subclinical atherosclerosis, the effects can be neutral or even detrimental. This distinction is crucial for understanding the long-term cardiovascular outcomes of estrogen therapy.

The timing of estrogen therapy initiation is a critical determinant of its cardiovascular effects, with early intervention offering a window of opportunity for cardioprotection.

The Healthy Endothelium Hypothesis a Mechanistic Explanation

To understand why timing is so important, we need to look at the health of the blood vessels themselves. The healthy endothelium hypothesis provides a compelling biological explanation for the timing hypothesis. The endothelium is the thin layer of cells that lines the inside of your blood vessels.

In a young, healthy woman, the endothelium is smooth and flexible, and it plays a active role in regulating blood flow and preventing the formation of blood clots. Estrogen helps to maintain this healthy endothelial function.

When estrogen therapy is initiated early in perimenopause, it acts on a healthy and responsive endothelium. It can continue to promote the production of nitric oxide, reduce inflammation, and prevent the adhesion of cholesterol-laden plaques to the vessel walls. However, with advancing age and prolonged estrogen deficiency, the endothelium can become dysfunctional.

It may lose its elasticity and become a site of chronic inflammation. If estrogen is introduced at this later stage, it may interact with a diseased and inflamed endothelium in a way that could potentially destabilize existing atherosclerotic plaques, leading to adverse cardiovascular events. This explains the different outcomes observed in younger versus older women in clinical trials.

Revisiting the Womens Health Initiative WHI

The WHI trials, published in the early 2000s, were landmark studies that had a profound impact on the use of MHT. The initial findings reported an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and breast cancer in women taking a combination of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA).

This led to a dramatic decrease in MHT prescriptions and a great deal of fear among women and their doctors. However, a closer look at the WHI data reveals a more complex story.

The average age of the women in the WHI trials was 63, and many were more than 10 years past menopause. When researchers re-analyzed the data, stratifying the participants by age and time since menopause, a different picture emerged.

In the younger women (ages 50-59) who were closer to the onset of menopause, MHT was associated with a trend toward a reduced risk of heart disease. The increased risks were primarily seen in the older women who started therapy many years after menopause. These findings provided strong support for the timing hypothesis and highlighted the importance of personalized risk assessment.

Key Findings from WHI Re-Analysis

- Younger Women (50-59 years) ∞ In this group, MHT was associated with a non-significant trend toward a lower risk of coronary heart disease. All-cause mortality was also significantly reduced in this age group.

- Older Women (60-79 years) ∞ The increased risk of cardiovascular events was concentrated in this group, particularly in women who were more than 20 years past menopause.

- Estrogen-Alone Trial ∞ In the WHI trial of estrogen-alone therapy (for women who had had a hysterectomy), the findings were even more favorable. In the 50-59 age group, estrogen therapy was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of heart attack and a composite measure of cardiovascular disease.

Choosing the Right Hormonal Optimization Protocol

When considering MHT, it is important to understand that there are many different options available. The choice of hormone, dose, and route of administration can all influence the potential benefits and risks. A personalized approach is essential, taking into account a woman’s individual symptoms, medical history, and preferences.

Here is a table outlining some of the common components of MHT protocols:

| Component | Description | Common Forms | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | The primary hormone for managing menopausal symptoms and providing cardiovascular benefits when initiated early. | Estradiol (bioidentical), Conjugated Equine Estrogens (CEE) | Estradiol is chemically identical to the estrogen produced by the ovaries. The route of administration (oral vs. transdermal) can affect cardiovascular risk. |

| Progestogen | Prescribed for women with a uterus to protect the uterine lining from the stimulating effects of estrogen. | Progesterone (bioidentical), Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA), Norethindrone | Micronized progesterone is often preferred as it may have a more favorable metabolic and cardiovascular profile compared to synthetic progestins like MPA. |

| Testosterone | Sometimes included in low doses to address symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and brain fog. | Testosterone Cypionate (injections), Testosterone pellets | Testosterone therapy in women should be carefully monitored by an experienced clinician to avoid side effects. |

The route of administration for estrogen is another important consideration. Transdermal estrogen (delivered via a patch, gel, or spray) bypasses the liver on its first pass, which may result in a lower risk of blood clots compared to oral estrogen. This makes transdermal estrogen a preferred option for many women, especially those with certain cardiovascular risk factors.

Ultimately, the decision about the most appropriate MHT protocol should be made in collaboration with a knowledgeable healthcare provider who can help you weigh the potential benefits and risks based on your unique health profile.

Academic

A deep exploration of the long-term cardiovascular outcomes of early estrogen therapy requires a move beyond clinical observations and into the realm of molecular biology. The cardioprotective effects of estrogen are not a matter of chance; they are the result of a complex and elegant interplay between the hormone and its receptors in the cardiovascular system.

Understanding these mechanisms at a cellular and genetic level provides the scientific foundation for the timing hypothesis and informs the development of more targeted and effective hormonal optimization protocols.

Estrogen’s influence on cardiovascular health is mediated primarily through two estrogen receptors ∞ estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). These receptors are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily and function as ligand-activated transcription factors.

When estrogen binds to ERα or ERβ in the nucleus of a cell, the receptor complex undergoes a conformational change, binds to specific DNA sequences called estrogen response elements (EREs), and regulates the transcription of target genes. This genomic pathway is responsible for many of the long-term effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system.

The cardiovascular benefits of early estrogen therapy are rooted in its intricate molecular interactions with estrogen receptors, which modulate gene expression and cellular function within the vasculature.

Genomic and Non-Genomic Actions of Estrogen

In addition to the classical genomic pathway, estrogen can also exert rapid, non-genomic effects through membrane-associated estrogen receptors (mERs). These receptors are located on the cell surface and, when activated by estrogen, can trigger intracellular signaling cascades, such as the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways.

These non-genomic actions are responsible for some of the immediate effects of estrogen on the vasculature, including the rapid vasodilation caused by the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and the production of nitric oxide.

The balance between genomic and non-genomic signaling is crucial for maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis. The expression and function of ERα and ERβ can change with age and in the presence of cardiovascular disease. For example, in a healthy endothelium, ERα is the predominant receptor and its activation leads to beneficial effects like vasodilation, reduced inflammation, and inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation.

However, in a diseased, atherosclerotic vessel, the expression of ERβ may increase, and the overall signaling environment can become pro-inflammatory. This shift in receptor expression and signaling may contribute to the differential effects of estrogen therapy observed in younger versus older women.

How Does Estrogen Modulate Vascular Health at the Molecular Level?

Estrogen’s cardioprotective effects are multifaceted, involving actions on various cell types within the cardiovascular system. Here’s a breakdown of some of the key molecular mechanisms:

- Endothelial Function ∞ Estrogen, primarily through ERα, stimulates the activity of eNOS, leading to increased production of nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator and also has anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic properties. Estrogen also reduces the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, making it less likely for inflammatory cells to stick to the vessel wall and initiate the process of atherosclerosis.

- Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) ∞ Estrogen inhibits the proliferation and migration of VSMCs, which are key events in the development of atherosclerotic plaques. This effect is mediated by both ERα and ERβ and involves the regulation of cell cycle proteins and growth factors.

- Inflammation ∞ Estrogen has potent anti-inflammatory properties. It can suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6, and it can inhibit the activation of NF-κB, a key transcription factor that drives the inflammatory response in the vasculature.

- Lipid Metabolism ∞ Estrogen has a favorable impact on the lipid profile, primarily by acting on the liver to increase the expression of LDL receptors, which enhances the clearance of LDL cholesterol from the circulation. It also increases the production of HDL cholesterol.

Key Clinical Trials and Their Contributions

Our current understanding of the cardiovascular effects of MHT is built upon decades of research, including several landmark clinical trials. The table below summarizes some of the most influential studies and their key findings.

| Trial Name | Year Published | Participants | Key Findings and Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) | 1998 | Postmenopausal women with established coronary heart disease (average age 67) | No overall benefit on cardiovascular events. An early increase in risk was observed, which discouraged the use of MHT for secondary prevention of heart disease. |

| Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) | 2002 | Large cohort of postmenopausal women (average age 63) | Initial reports showed an increased risk of cardiovascular events with combined MHT. This led to a sharp decline in MHT use. Subsequent analyses revealed the importance of timing. |

| Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS) | 2012 | Recently menopausal women (average age 50) | After 10 years of treatment, women receiving MHT had a significantly reduced risk of mortality, heart failure, and myocardial infarction, with no increased risk of cancer or stroke. |

| Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) | 2016 | Postmenopausal women stratified by time since menopause (<6 years vs. >10 years) | Early initiation of estrogen therapy was associated with a significant reduction in the progression of atherosclerosis (measured by carotid intima-media thickness) compared to late initiation. This provided strong support for the timing hypothesis. |

The collective evidence from these and other studies has led to a paradigm shift in our understanding of MHT. The focus has moved away from a one-size-fits-all approach to a personalized strategy that considers a woman’s age, time since menopause, and individual risk profile.

For women who are candidates for MHT, initiating therapy early in perimenopause appears to be a safe and effective way to manage symptoms and may offer the additional benefit of long-term cardiovascular protection. This approach aligns with the principles of preventative medicine and empowers women to take a proactive role in their long-term health.

References

- Rossouw, J. E. et al. “Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women ∞ principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial.” JAMA 288.3 (2002) ∞ 321-333.

- Manson, J. E. et al. “Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification.” New England Journal of Medicine 356.25 (2007) ∞ 2591-2602.

- Schierbeck, L. L. et al. “Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women ∞ randomised, open-label, controlled trial.” BMJ 345 (2012) ∞ e6409.

- Hodis, H. N. et al. “Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol.” New England Journal of Medicine 374.13 (2016) ∞ 1221-1231.

- The NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. “The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society.” Menopause 29.7 (2022) ∞ 767-794.

- Mendelsohn, M. E. and R. H. Karas. “The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system.” New England Journal of Medicine 340.23 (1999) ∞ 1801-1811.

- Grodstein, F. et al. “Postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality.” New England Journal of Medicine 355.8 (2006) ∞ 753-761.

- Salpeter, S. R. et al. “Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women.” The American journal of medicine 122.11 (2009) ∞ 1016-1022.

- Boardman, H. M. et al. “Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4 (2015).

- Harman, S. M. et al. “KEEPS ∞ The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study.” Climacteric 17.sup1 (2014) ∞ 3-12.

Reflection

The journey through perimenopause and beyond is a deeply individual one. The information presented here provides a framework for understanding the intricate relationship between your hormones and your cardiovascular health. It is a starting point for a conversation, not a conclusion.

Your unique biology, your personal history, and your future goals all play a role in shaping the path that is right for you. The knowledge you have gained is a powerful tool. It allows you to ask informed questions, to seek out a healthcare partner who listens and understands, and to become an active participant in your own wellness.

Consider where you are in your own journey. What are your primary concerns? What are your goals for your health in the next five, ten, or twenty years? The answers to these questions are the foundation of a personalized wellness protocol.

The science of hormonal health is constantly evolving, and the most effective strategies are those that are tailored to the individual. Your body is a complex and intelligent system. By listening to its signals and providing it with the support it needs, you can navigate this transition with strength, grace, and a renewed sense of vitality. The power to shape your future health lies within you.