Fundamentals

The decision to cease a testosterone optimization protocol marks a significant transition within your body’s internal environment. You have moved from a state of externally supported hormonal stability to a phase of profound biological recalibration. This experience is unique to each individual, yet it is governed by a universal physiological system ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

Understanding this system is the first step toward comprehending the downstream effects on your cardiovascular health. Your body is not simply returning to a baseline; it is actively working to re-establish a complex, self-regulating hormonal cascade that was temporarily dormant.

Think of the HPG axis as the master control system for your body’s natural testosterone production. It operates as a sophisticated feedback loop. The hypothalamus, a small region at the base of your brain, detects the body’s need for testosterone and releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH).

This chemical messenger travels a short distance to the pituitary gland, instructing it to produce Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). These hormones then enter the bloodstream and travel to the testes, where LH directly stimulates the Leydig cells to produce testosterone.

When testosterone levels are sufficient, they send a signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to slow down the release of GnRH and LH, maintaining a precise balance. This entire process is a delicate and continuous conversation between your brain and your gonads.

The Axis during and after Therapy

When you began a therapeutic protocol involving weekly injections of Testosterone Cypionate, you introduced an external, powerful source of testosterone into your system. Your body, in its efficiency, recognized that circulating testosterone levels were consistently high. In response, the HPG axis powered down.

The hypothalamus reduced its GnRH signals, the pituitary ceased its LH production, and your testes’ own testosterone synthesis went quiet. This is a normal and expected physiological response. The system was placed in a state of managed hibernation because the end-product, testosterone, was being supplied from an outside source.

The moment you discontinue this external support, the axis is tasked with restarting itself from a cold start. The circulating therapeutic testosterone begins to clear from your system, and your brain eventually detects that levels are falling below the optimal threshold. This is the trigger for the hypothalamus to begin producing GnRH again.

The process, however, is not instantaneous. The pituitary gland and the testes have been dormant and require time to reawaken and synchronize their functions. This period between the cessation of therapy and the full restoration of your natural production is a transient state of induced hypogonadism. It is within this window of low testosterone that the conversation about cardiovascular outcomes begins.

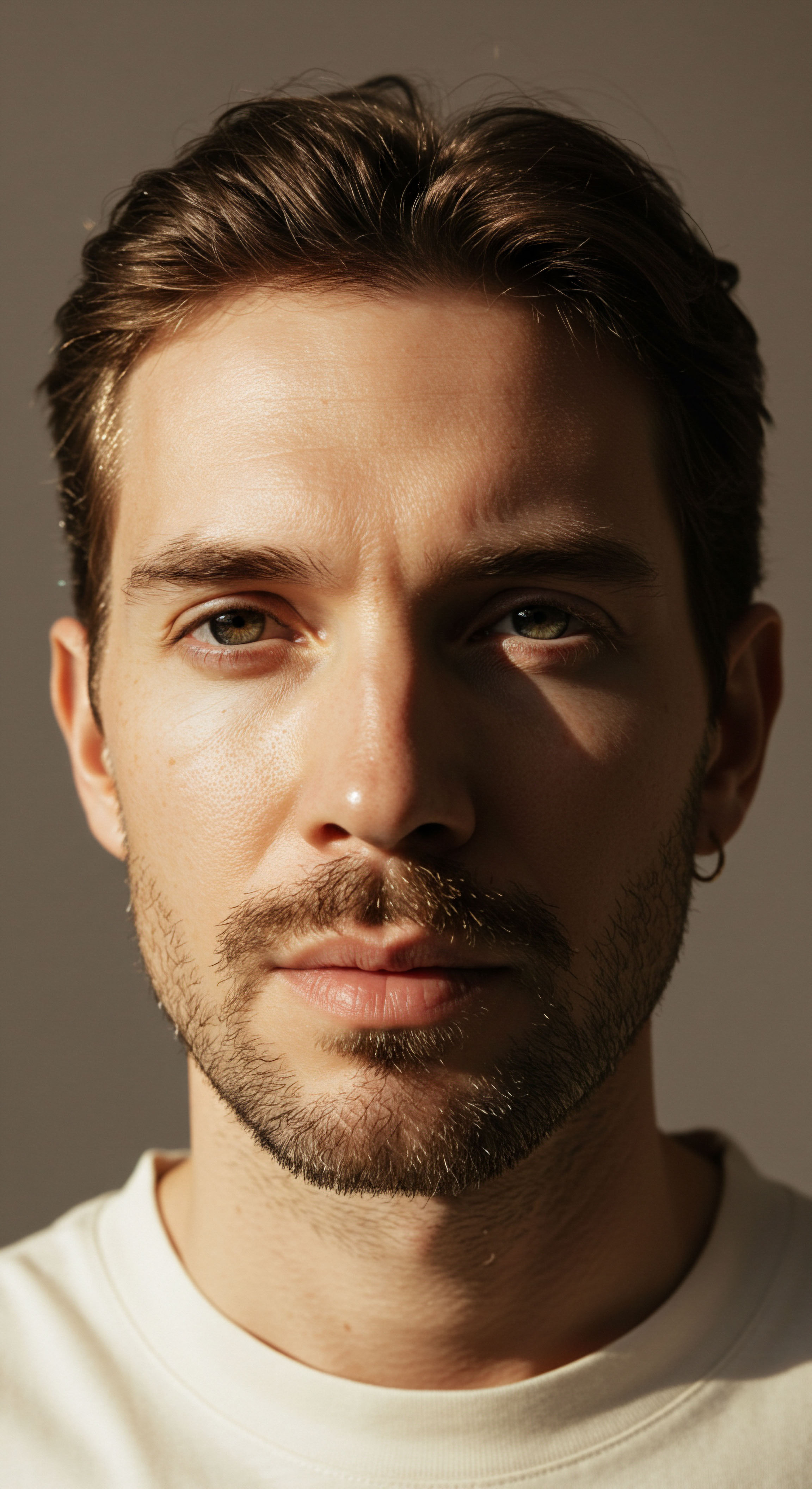

Upon stopping testosterone therapy, the body enters a critical recalibration phase, working to restart its own dormant hormonal production axis.

Why Does This Transitionary State Matter for Your Heart?

Testosterone is a powerful metabolic regulator, and its influence extends far beyond muscle mass and libido. Its presence is deeply intertwined with the systems that govern cardiovascular wellness. The physiological benefits you likely experienced during your protocol ∞ improved body composition, better insulin sensitivity, and favorable changes in certain inflammatory markers ∞ are directly linked to maintaining an optimal testosterone level.

The temporary absence of this hormone during the HPG axis restart phase means the reversal of these protective mechanisms. This is the core of the issue. The long-term cardiovascular outcomes following discontinuation are shaped by the duration and severity of this interim hypogonadal state and how your body navigates it.

Consider the direct relationship between testosterone and body composition. Optimal testosterone levels promote the growth of lean muscle mass and discourage the accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), the metabolically active fat stored deep within the abdominal cavity. VAT is a primary producer of inflammatory signals that contribute to systemic inflammation, a known driver of atherosclerosis.

When testosterone levels fall during the post-cessation period, the body’s metabolic preference shifts. It becomes easier to lose muscle and accumulate VAT. This change in body composition is a foundational step that can alter cardiovascular risk. Your journey after discontinuation is about managing this transition and supporting your body’s return to its own robust, self-sustaining hormonal equilibrium.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of the HPG axis, we can now examine the specific biochemical shifts that occur when testosterone therapy is withdrawn. The cardiovascular system, which had adapted to a state of hormonal optimization, must now contend with a period of relative deficiency.

This phase is characterized by measurable changes in lipid metabolism, glycemic control, and vascular function. The trajectory of your long-term cardiovascular health is influenced by how efficiently your body mitigates these changes and restores its endogenous hormonal balance. Protocols involving agents like Gonadorelin or Clomiphene are designed specifically to shorten this vulnerable window.

The Reversal of Metabolic Benefits

During a structured TRT protocol, your body experiences a cascade of positive metabolic adjustments. Testosterone directly influences enzymes and cellular processes that govern how your body handles fats and sugars. Upon discontinuation, these benefits begin to systematically reverse. This is a physiological certainty. The key variables are the speed of this reversal and the length of time your body spends in a metabolically disadvantaged state before your natural production fully recovers.

How Does Discontinuation Alter Lipid Profiles?

One of the most immediate and quantifiable consequences of stopping testosterone therapy is the alteration of your serum lipid panel. Testosterone has a complex effect on cholesterol and triglycerides, and its withdrawal triggers a predictable shift. During therapy, many individuals observe a decrease in High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, often called “good” cholesterol, due to testosterone’s effect on an enzyme called hepatic lipase.

Concurrently, there can be a beneficial reduction in Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides. The net effect on cardiovascular risk during therapy is debated and highly individual. Upon cessation, these trends reverse.

As testosterone levels fall, hepatic lipase activity decreases, which typically allows HDL levels to rise. While this may seem beneficial, it occurs alongside a potential increase in LDL and triglyceride levels, which are more directly implicated in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

The environment shifts from one state of metabolic control to another, and this new state, characterized by low testosterone, is generally associated with a more atherogenic lipid profile. Understanding this allows you to anticipate these changes and monitor them with your physician.

| Lipid Marker | Common Trend During TRT | Anticipated Trend After Discontinuation | Underlying Metabolic Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol | May decrease or remain stable | Potential for increase | Complex interplay of hepatic synthesis and clearance, influenced by androgen levels. |

| LDL Cholesterol | Often decreases | Potential for increase toward pre-treatment or higher levels | Testosterone can enhance LDL receptor expression in the liver, promoting clearance. This effect is lost. |

| HDL Cholesterol | Often decreases | Tends to increase | Testosterone increases the activity of hepatic lipase, which breaks down HDL particles. Cessation reverses this. |

| Triglycerides | Often decrease | Potential for increase | Testosterone improves insulin sensitivity, which helps regulate triglyceride levels. This benefit recedes. |

Glycemic Control and Vascular Health

Testosterone is a key player in maintaining insulin sensitivity. It facilitates the process by which your cells take up glucose from the blood for energy, partly by supporting the function of GLUT4 transporters in muscle tissue. This is why many men on TRT report more stable energy levels and find it easier to manage their body composition.

When therapy is halted, this advantage diminishes. The resulting decrease in insulin sensitivity means your body must produce more insulin to manage the same amount of glucose, a condition known as hyperinsulinemia. This state is pro-inflammatory and places additional stress on the pancreas and the entire cardiovascular system.

The period following TRT cessation is defined by a reversal of metabolic advantages, impacting lipids, insulin sensitivity, and vascular tone.

Simultaneously, testosterone supports endothelial health. The endothelium is the thin layer of cells lining your blood vessels, and its function is critical for cardiovascular wellness. It produces nitric oxide (NO), a molecule that allows blood vessels to relax and widen, promoting healthy blood flow and pressure. Testosterone supports NO synthesis.

As testosterone levels drop post-discontinuation, this support is withdrawn, potentially leading to reduced endothelial function and increased vascular stiffness. This creates an environment where blood pressure may rise and the vessels themselves are less resilient.

Accelerating the Restart Post-Therapy

Given these potential negative shifts, the clinical goal after stopping TRT is to minimize the duration of the hypogonadal state. This is the purpose of a Post-TRT or Fertility-Stimulating Protocol. These are not passive approaches; they are active interventions designed to “jump-start” the HPG axis.

- Gonadorelin ∞ This is a synthetic form of GnRH. By administering it, you are directly signaling the pituitary gland to wake up and produce LH and FSH, bypassing the need to wait for the hypothalamus to initiate the signal. It acts as a powerful primary stimulus to the system.

- Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) ∞ This compound works at the level of the hypothalamus. It is a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM) that blocks estrogen receptors in the brain. Your brain interprets this as a lack of estrogen (which is produced from testosterone), and in response, it ramps up GnRH production to drive the whole axis harder.

- Tamoxifen ∞ Another SERM, similar in function to Clomiphene, that also serves to stimulate the HPG axis by blocking estrogen feedback at the hypothalamus and pituitary.

- Anastrozole ∞ An aromatase inhibitor that may be used cautiously. By blocking the conversion of the newly produced testosterone into estrogen, it keeps estrogen levels low, further preventing the negative feedback that could slow the HPG axis restart.

By employing these tools, a clinician aims to shorten the period of metabolic and vascular vulnerability. The faster your body’s own testosterone production is restored, the quicker the protective effects on lipid profiles, insulin sensitivity, and endothelial function can be re-established, thereby shaping a more favorable long-term cardiovascular outcome.

Academic

An academic exploration of the long-term cardiovascular sequelae following the cessation of testosterone replacement therapy requires a systems-biology perspective. The focal point is the transient hypogonadal state and its multifaceted impact on cardiometabolic homeostasis. The duration and depth of this state dictate the magnitude of risk.

This is governed by the individual’s HPG axis resilience, the specific pharmacokinetics of the discontinued testosterone ester, and the presence or absence of a structured restart protocol. The analysis must extend beyond simple lipid markers to encompass inflammation, endothelial biology, hemodynamics, and even cardiac morphology.

The Inflammatory Milieu of Hypogonadism

The withdrawal of therapeutic testosterone initiates a shift toward a pro-inflammatory state, a critical driver of atherosclerotic disease progression. Testosterone exerts suppressive effects on the production of several key inflammatory cytokines. When androgenic support is removed, the innate immune system’s calibration is altered. Macrophages and adipocytes, particularly those within visceral adipose tissue, increase their output of inflammatory mediators.

Specifically, low testosterone levels are correlated with elevated serum concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α). These molecules are not passive bystanders; they are active participants in vascular pathology. TNF-α and IL-6 promote the expression of adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1.

This makes the vessel lining “stickier,” facilitating the recruitment of monocytes from the bloodstream into the subendothelial space. Once there, these monocytes differentiate into macrophages, ingest oxidized LDL cholesterol, and become foam cells ∞ the foundational units of an atherosclerotic plaque. The post-discontinuation period is therefore a window of heightened inflammatory potential, which can accelerate plaque formation or, more dangerously, contribute to the instability of existing plaques, increasing the risk of rupture and subsequent thrombotic events.

What Determines the Speed of HPG Axis Recovery?

The timeline for restoring endogenous eugonadism is highly variable and is a central determinant of long-term cardiovascular outcomes. Several factors dictate this recovery trajectory:

- Duration and Dose of Therapy ∞ Longer periods of high-dose TRT can induce a more profound and prolonged suppression of the HPG axis, requiring a more extended recovery period.

- Baseline Gonadal Function ∞ An individual who had robust testicular function before starting TRT (e.g. for non-medical performance enhancement) will likely recover more quickly than an individual with pre-existing primary or secondary hypogonadism.

- Age ∞ The functional capacity and responsiveness of the Leydig cells and the pituitary gland naturally decline with age, which can slow the restart process.

- Use of Ancillary Therapies ∞ The concurrent use of agents like HCG or Gonadorelin during the TRT cycle itself can keep the testes responsive and significantly shorten the post-cessation recovery time.

- Genetic Factors ∞ Individual genetic variations in hormone receptors and enzyme activity also play a role in the speed and completeness of recovery.

Hemodynamic and Rheological Considerations

Testosterone therapy is known to stimulate erythropoiesis, leading to an increase in red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. This can increase blood viscosity. While this effect is monitored during therapy to mitigate thrombotic risk, the reversal of this process upon discontinuation has its own set of consequences.

As testosterone levels fall, erythropoietin signaling decreases, and hematocrit levels gradually return to the individual’s baseline. This reduction in blood viscosity is a clear cardiovascular benefit, potentially lowering the risk of venous thromboembolism and reducing cardiac workload.

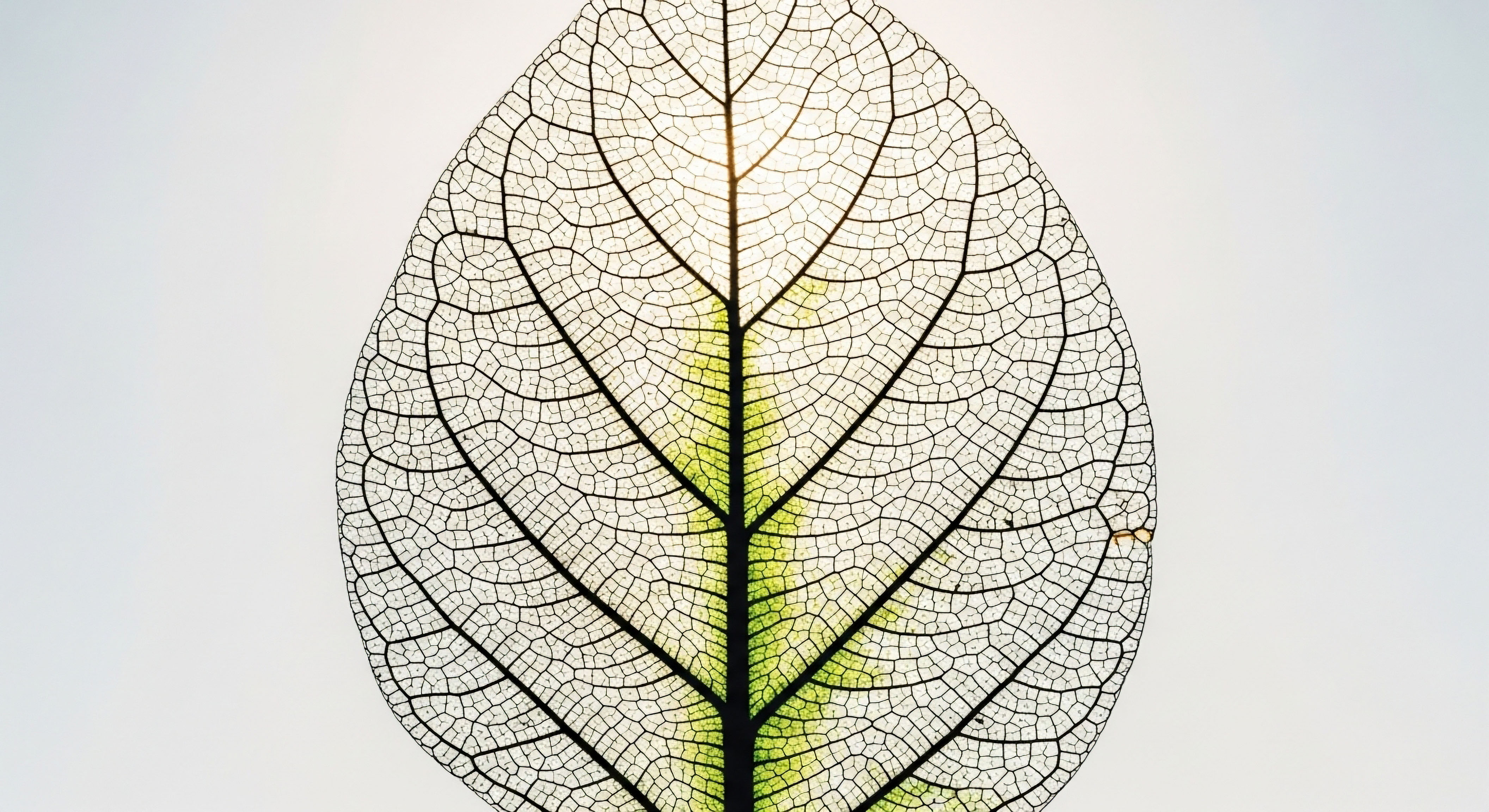

The post-TRT phase initiates a complex interplay between the beneficial normalization of blood viscosity and the detrimental rise of systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

This positive hemodynamic adjustment occurs concurrently with the negative metabolic shifts previously discussed. This creates a complex risk-benefit dynamic. The TRAVERSE trial, a landmark study on TRT safety, found no overall increase in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) during therapy but did report a statistically significant increase in the incidence of atrial fibrillation and a potential for acute kidney injury.

While the study did not assess discontinuation, these findings suggest that testosterone’s influence on cardiac electrophysiology and renal function is complex. The withdrawal of this influence could theoretically have its own rebound effects, although this remains an area requiring dedicated research. The increased risk of atrial fibrillation seen in some studies could be linked to testosterone’s effects on cardiac remodeling or ion channel function, and how the heart adapts to its absence is a critical unknown.

| Biological System | Effect of TRT Cessation | Mechanism and Cardiovascular Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine (HPG Axis) | Initiation of a transient hypogonadal state. | The duration of low testosterone dictates the exposure time to other risk factors. A slow recovery prolongs metabolic and inflammatory stress. |

| Metabolic (Lipids & Glucose) | Shift toward an atherogenic lipid profile (higher LDL/Trigs) and decreased insulin sensitivity. | Promotes the fundamental building blocks of atherosclerosis and creates a pro-inflammatory state of hyperinsulinemia, stressing the vasculature. |

| Inflammatory | Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (CRP, IL-6, TNF-α). | Enhances endothelial dysfunction, promotes plaque formation, and increases the risk of plaque instability, a direct precursor to myocardial infarction and stroke. |

| Hematologic | Normalization of hematocrit and decreased blood viscosity. | This is a primary beneficial outcome, reducing the risk of thromboembolic events and lowering the overall workload on the heart. |

| Vascular | Reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and potential for increased endothelial dysfunction. | Leads to arterial stiffness, potential for increased blood pressure, and reduced capacity for vasodilation, impairing blood flow regulation. |

| Body Composition | Loss of lean muscle mass and preferential gain of visceral adipose tissue (VAT). | VAT is a metabolically active organ that secretes inflammatory cytokines, directly contributing to systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. |

The Unanswered Question of Cardiac Remodeling

Androgens can influence cardiac structure, with some evidence suggesting a potential for increased left ventricular mass in response to long-term, high-dose therapy, similar to the athletic heart. This is a physiological adaptation to increased workload and metabolic demand. A critical academic question is how the heart remodels following the withdrawal of this stimulus. Does the left ventricular mass regress? And if so, does this process occur uniformly, or could it transiently alter cardiac function or electrophysiological stability?

The cessation of TRT represents a significant systemic event. The long-term cardiovascular outcomes are not a single, predetermined path. They are the net result of a dynamic interplay between the beneficial normalization of hematocrit and the potentially deleterious consequences of metabolic dysregulation and systemic inflammation that characterize the transient hypogonadal window. The clinical management of this period, particularly through protocols aimed at accelerating HPG axis recovery, is therefore of paramount importance in shaping a favorable long-term cardiovascular prognosis.

References

- Lincoff, A. M. Bhasin, S. Flevaris, P. Mitchell, L. M. Basaria, S. Boden, W. E. & TRAVERSE Study Investigators. (2023). Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 389 (2), 107 ∞ 117.

- Gravholt, C. H. Chang, S. Wallentin, M. Fedder, J. Moore, P. & Skakkebæk, A. (2024). Cardiovascular risk and mortality in men receiving testosterone replacement therapy for Klinefelter syndrome in Denmark ∞ a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 12 (2), 116-126.

- Le, H. & Oh, J. (2016). Long-term Testosterone May Decrease Cardiovascular Risk. Medscape. Retrieved from a presentation at the American Urological Association 2016 Annual Meeting.

- Jones, T. H. (2024). Long Term Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone Therapy ∞ A Review of the TRAVERSE Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- Basaria, S. Coviello, A. D. Travison, T. G. Storer, T. W. Farwell, W. R. Jette, A. M. & Bhasin, S. (2010). Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. New England Journal of Medicine, 363 (2), 109-122.

- Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. (2024). Research Finds Testosterone Therapy Safe for Heart Health. Cedars-Sinai Newsroom.

- Saad, F. Röhrig, G. von Haehling, S. & Traish, A. (2017). Testosterone deficiency and testosterone treatment in older men. Gerontology, 63 (2), 144-156.

Reflection

Charting Your Body’s Next Chapter

You have navigated a period of profound, externally guided physiological optimization. The knowledge you have gained about your body’s response to hormonal inputs is invaluable. Now, as you move into a phase of self-regulation, the data points and mechanisms discussed here become your tools for introspection and informed dialogue.

The path forward is about observing your body’s unique recalibration process with a new level of awareness. How does your energy shift? How does your body composition respond? How does your sense of well-being evolve as your internal systems come back online?

This information is designed to transform uncertainty into curiosity. It provides a framework for understanding the biological narrative unfolding within you. Your personal health journey is a continuum, and this transition is but one chapter. The ultimate goal is to achieve a state of vitality that is sustainable and internally generated.

Consider this knowledge not as a final destination, but as a detailed map that empowers you to ask deeper questions and to partner with your clinical guide in charting the course ahead with confidence and precision.

Glossary

hpg axis

pituitary gland

testosterone levels

cardiovascular outcomes

low testosterone

insulin sensitivity

body composition

long-term cardiovascular outcomes

visceral adipose tissue

systemic inflammation

testosterone levels fall

cardiovascular risk

testosterone therapy

gonadorelin

clomiphene

lipid profile

endothelial function

adipose tissue

hypogonadism

blood viscosity