Fundamentals

You feel it in your bones, a subtle shift in energy, a change in the way your body responds to the day. This internal experience is profoundly real, a direct communication from your body’s intricate signaling network. When we discuss workplace wellness incentives, we are having a conversation about external pressures attempting to influence this deeply personal, biological reality.

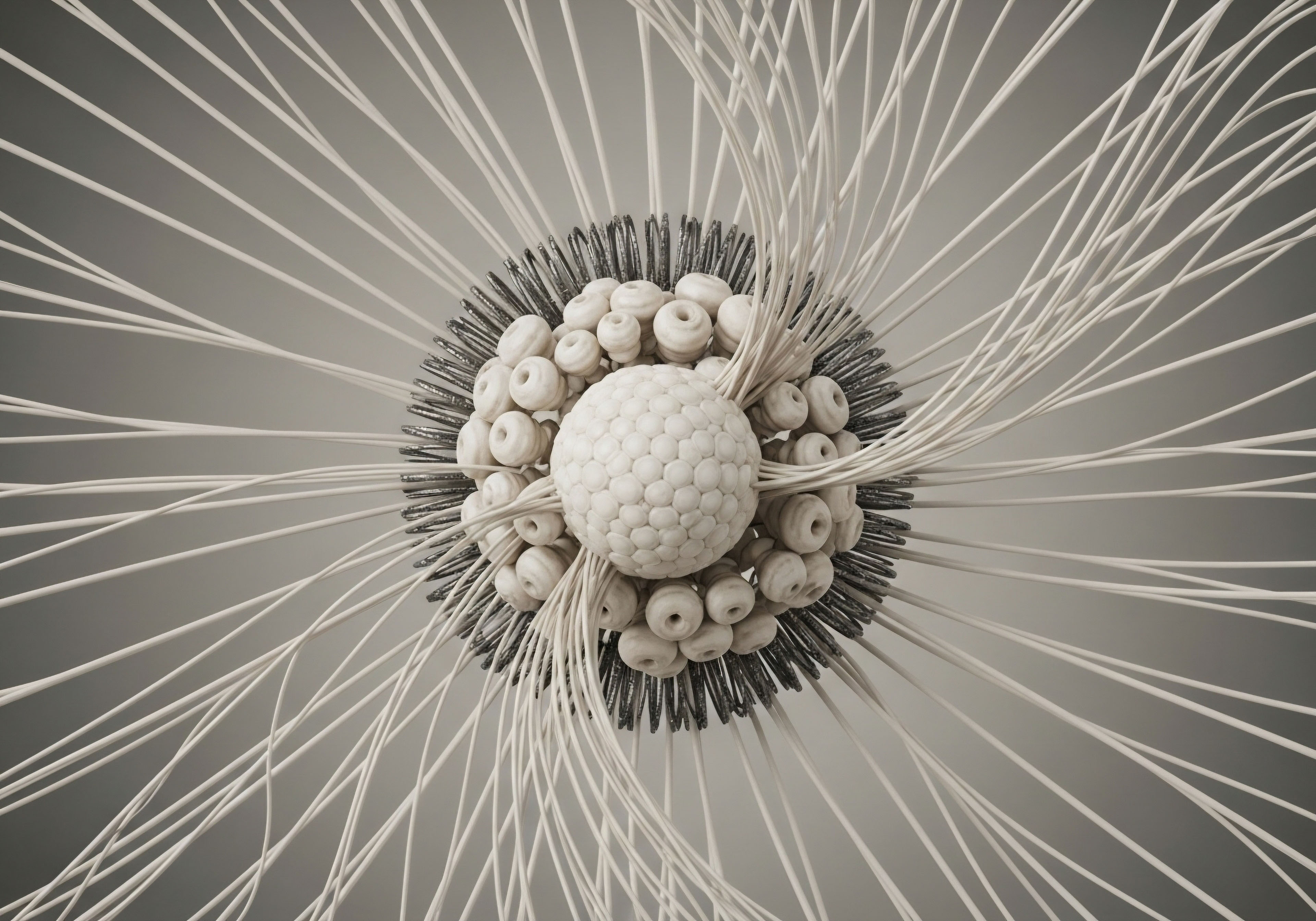

The discussion begins with the lived experience of your own physiology. Your body operates on a complex set of instructions, a biochemical language of hormones and metabolic signals that dictate everything from your energy levels to your stress response. Understanding this internal ecosystem is the first step toward reclaiming vitality on your own terms.

At the heart of this conversation are the legal and ethical guardrails designed to protect your autonomy. Laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) form a foundational framework.

HIPAA, for instance, was created to prevent discrimination based on health status, yet it includes specific exceptions for bona fide wellness programs. This creates a landscape where employers can legally offer financial rewards for participation in programs aimed at improving health metrics like cholesterol or blood pressure. The intention is to encourage healthier lifestyles, which can lead to a more productive workforce and lower healthcare expenditures for the company.

A person’s internal hormonal and metabolic state is a deeply private and complex biological reality that workplace wellness programs aim to influence through external incentives.

The core of the issue emerges when these programs transition from encouragement to something that feels coercive. The line is a fine one. A program is generally considered voluntary if the incentive is a reward, a “carrot,” rather than a penalty, a “stick.” However, the distinction can become blurred.

If a financial reward is substantial enough, the choice to opt-out may not feel like a genuine choice at all, especially for employees in precarious financial situations. This is where the ethical dimension becomes paramount. A truly ethical program respects individual autonomy, ensuring that participation is a free and informed decision, not a response to undue pressure.

This is particularly relevant when considering the deeply personal nature of hormonal and metabolic health. Conditions like obesity or nicotine addiction are recognized as medical conditions, yet they are often the very targets of these incentive programs. Penalizing an individual for a metric like body mass index (BMI) fails to account for the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and the endocrine system.

It reduces a person’s health to a single number, ignoring the personal journey and the biological realities that contribute to that number. This is where the conversation must shift from population-level statistics to the individual, validating their experience and acknowledging the biological systems at play.

Intermediate

To truly grasp the complexities of workplace wellness incentives, we must move beyond a surface-level understanding of the law and delve into the specific mechanisms of both the programs and our own physiology. The legal architecture, primarily shaped by HIPAA, the ACA, ADA, and GINA, creates a specific operational space for these programs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), for example, expanded the scope of what employers could do, allowing for outcome-based incentives. This means an employer can reward an employee for achieving a specific health outcome, such as a target cholesterol level, not just for participating in a health education class.

However, these regulations come with critical stipulations. To be compliant, a wellness program must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease. It cannot be a subterfuge for discrimination. For outcome-based programs, this means providing a “reasonable alternative standard” for individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the specified target.

For instance, an employee with a genetic predisposition to high cholesterol must be offered an alternative way to earn the reward, such as by following a doctor’s dietary recommendations or participating in a relevant health coaching program. This provision is a direct acknowledgment that health outcomes are not solely a matter of willpower.

The Hormonal Connection to Workplace Stress

How does this connect to your internal world? Consider the body’s primary stress response system ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. When you perceive stress ∞ whether from a work deadline or the pressure to meet a wellness target ∞ your hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

This signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. Chronic activation of this system, which can be exacerbated by the pressure of wellness programs, can lead to a state of hormonal dysregulation. This can manifest as fatigue, weight gain, and a host of other symptoms that ironically may make it even harder to meet the wellness targets.

This creates a potential feedback loop where the program designed to improve health inadvertently contributes to the very conditions it aims to prevent. From a clinical perspective, this is a critical flaw. A person’s inability to lower their blood pressure might be directly linked to the chronic stress induced by the program itself. Therefore, a truly effective and ethical program must consider the potential for such iatrogenic, or treatment-induced, consequences.

Are All Wellness Incentives Created Equal?

The design of the incentive itself is a critical variable. A program that offers a small discount on a gym membership is fundamentally different from one that ties a significant portion of an employee’s health insurance premium to their BMI. The latter can feel punitive and create a culture of shame and anxiety around health. It also disproportionately affects those with chronic conditions, who may already be facing higher healthcare costs and the emotional burden of managing their health.

Here is a comparison of two common approaches:

| Incentive Model | Description | Potential Ethical Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Participation-Based | Employees receive a reward for completing a health-related activity, such as a health risk assessment or attending a seminar. | Lower risk of being coercive, but may not lead to meaningful health improvements. |

| Outcome-Based | Employees receive a reward for achieving a specific health metric, such as a certain BMI or blood pressure reading. | Higher risk of being coercive and discriminatory if not designed with reasonable alternative standards. Can create undue pressure and stress. |

Ultimately, the conversation must be elevated to one of health equity. A one-size-fits-all approach to wellness fails to recognize the diverse needs and circumstances of a workforce. An ethical framework requires a shift in focus from simply reducing costs to genuinely supporting the well-being of every employee, acknowledging the complex biological and social determinants of health.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of workplace wellness incentives requires a multi-layered approach, integrating legal precedent, ethical theory, and a deep understanding of endocrinology and metabolic science. The legal framework, while providing a set of rules, is predicated on a set of assumptions about health, behavior, and responsibility that are worth interrogating from a scientific perspective.

The allowance for outcome-based incentives under the ACA, for example, implicitly endorses a biomedical model of health that can be reductionist. It suggests that complex health outcomes can be neatly distilled into a few key biomarkers and that these biomarkers are largely within an individual’s control. This perspective often fails to adequately account for the profound influence of the endocrine system, genetics, and socio-economic factors.

The Endocrinology of Coercion

From a neuro-endocrinological standpoint, the very structure of some wellness programs can be seen as a source of chronic, low-grade stress. The constant monitoring, the pressure to meet targets, and the financial stakes can activate the HPA axis in a sustained manner.

This chronic elevation of cortisol has well-documented, deleterious effects on the body. It can induce insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes, and promote the deposition of visceral adipose tissue, the metabolically active fat that surrounds the organs. Thus, a program aimed at reducing obesity could, in a cruel irony of physiology, be contributing to the very metabolic dysregulation it seeks to correct.

The pressure to meet arbitrary wellness targets can create a state of chronic stress, leading to hormonal imbalances that may undermine the program’s intended health benefits.

Furthermore, the ethical principle of “voluntariness” becomes suspect when viewed through a neurobiological lens. The human brain is exquisitely sensitive to reward and punishment. A significant financial incentive activates the mesolimbic dopamine system, the brain’s primary reward pathway. This is the same system implicated in addiction.

When a person’s health insurance, a fundamental necessity, is tied to achieving a certain health outcome, the choice to participate is not a purely rational one. It is a decision heavily influenced by the powerful neurochemical drive to avoid loss and seek reward. This raises the question of whether “voluntary” is a meaningful descriptor in this context.

Discrimination at the Cellular Level

The issue of discrimination also takes on a new dimension when considered from a hormonal and metabolic perspective. Consider two employees, one with a genetic predisposition to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and another with no such predisposition. PCOS is a complex endocrine disorder that can cause insulin resistance, weight gain, and irregular menstrual cycles.

A wellness program that uses BMI as a primary metric will inherently disadvantage the employee with PCOS, for whom weight management is a significant clinical challenge. The “reasonable alternative standard” is a legal attempt to address this, but it often falls short of true equity. The very act of having to seek an exemption can be stigmatizing and reinforces a sense of being “othered.”

This table illustrates how a standard wellness metric can have a disproportionate impact:

| Health Metric | Standard Target | Potentially Disadvantaged Group | Underlying Biological Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | < 25 | Individuals with PCOS, hypothyroidism, or certain genetic predispositions. | Hormonal imbalances affecting metabolism and fat storage. |

| Blood Pressure | < 120/80 mmHg | Individuals with a genetic predisposition to hypertension or those experiencing chronic stress. | Dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system. |

| Fasting Glucose | < 100 mg/dL | Individuals with pre-diabetes or insulin resistance. | Impaired insulin signaling at the cellular level. |

What Is the True Purpose of Workplace Wellness Programs?

This leads to a fundamental question about the telos, or ultimate purpose, of these programs. Are they genuinely aimed at improving employee health, or are they primarily a mechanism for cost-shifting?

Some analyses suggest that the savings from wellness programs come not from a healthier workforce, but from shifting a greater share of healthcare costs onto those with chronic conditions, who are less likely to meet the program’s targets. If this is the case, then these programs are not wellness initiatives at all; they are a form of regressive health financing, disguised in the language of personal responsibility.

A truly ethical and effective program would need to be radically reimagined. It would move away from a focus on simplistic, often misleading, biomarkers and toward a more holistic and individualized approach. It would recognize that health is not a commodity to be bought or sold, but a complex, dynamic state that is deeply intertwined with an individual’s biology, psychology, and social context. It would, in short, treat employees as human beings, not as data points on a corporate dashboard.

References

- Weber, Leonard. “Wellness Programs ∞ Legality, Fairness, and Relevance.” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 9, no. 12, 2007, pp. 845-849.

- Cavico, Frank J. and Bahaudin G. Mujtaba. “Corporate Wellness Programs ∞ Implementation Challenges in the Modern American Workplace.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management, vol. 5, no. 10, 2016, pp. 565-569.

- Cavico, Frank J. et al. “Wellness Programs in the Workplace ∞ An Unfolding Legal Quandary for Employers.” Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, vol. 18, no. 1, 2015, pp. 41-66.

- “Ethical Considerations in Workplace Wellness Programs.” Corporate Wellness Magazine, 28 July 2023.

- Goetzel, Ron Z. “Structuring Legal, Ethical, And Practical Workplace Health Incentives ∞ A Reply to Horwitz, Kelly, And DiNardo.” Health Affairs Forefront, 23 April 2013.

Reflection

You have now seen the external landscape of laws and the internal landscape of your own biology. The intersection of these two worlds is where your personal health journey unfolds. The information presented here is a map, but you are the one who must navigate the territory.

The knowledge of how your body’s systems work, how they respond to stress, and how they are influenced by the world around you is the most powerful tool you possess. Your health is not a problem to be solved by an employer’s incentive program. It is a dynamic, lifelong process of learning, adapting, and recalibrating.

The path forward is one of self-knowledge and informed advocacy, a journey toward a state of well-being that is defined not by external metrics, but by your own vitality and sense of wholeness.

Glossary

workplace wellness incentives

genetic information nondiscrimination act

americans with disabilities act

wellness programs

blood pressure

wellness incentives

outcome-based incentives

cortisol

health insurance

health equity

workplace wellness

hpa axis