Fundamentals

You have likely encountered a workplace wellness initiative. It may have presented as a simple invitation to a health seminar, a request to complete a health risk assessment, or a program offering a financial incentive for achieving specific biometric targets.

Your personal reaction to these programs is a direct reflection of their design and, more importantly, the legal and ethical frameworks that govern them. Understanding this architecture is the first step in ensuring these programs serve your personal health journey, validating your biological individuality rather than penalizing it.

At the highest level, the regulatory landscape, shaped by laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA), organizes wellness programs into two distinct categories. This classification is the foundational element that determines the rules a program must follow and the rights you possess as a participant. The two types of programs are participatory and health-contingent.

The Nature of Participatory Wellness Programs

A participatory wellness program is structured around engagement. Its core principle is to reward the act of taking part in a health-related activity. The reward you earn is disconnected from any specific health outcome or biomarker. Think of it as credit for showing up to the class, regardless of your final grade. The program’s success, from a design perspective, is measured by your involvement.

Examples of these programs are common and often form the backbone of a company’s initial wellness efforts. They include:

- Attending a lunch-and-learn seminar on nutrition or stress management.

- Completing a Health Risk Assessment (HRA) questionnaire, without any reward tied to the answers you provide.

- Joining a company-sponsored walking club or fitness class.

- Receiving a reimbursement for a portion of your gym membership fee.

The legal requirements for these programs are minimal under HIPAA and the ACA because they pose a lower risk of discrimination based on health status. They invite everyone to the table under the same terms. Their purpose is to make health resources available and encourage a baseline level of health consciousness across an entire workforce.

The Architecture of Health-Contingent Wellness Programs

A health-contingent wellness program introduces a layer of biological specificity. It directly links a reward to your ability to meet a specific health standard. This design moves from rewarding action to rewarding a particular physiological state. The program requires you to achieve a defined outcome, making your personal health data the currency for the incentive. This is where the legal framework becomes significantly more complex and robust, as the potential for discrimination against individuals with underlying health factors increases.

A health-contingent program’s structure is what necessitates a complex web of legal protections to ensure fairness for all participants.

These programs are themselves divided into two subcategories, each with a slightly different focus:

- Activity-Only Programs ∞ This type requires you to perform a specific physical activity to earn a reward. For example, you might be required to walk a certain number of steps per day or participate in a formal exercise program. It is more demanding than simply signing up for a gym; it requires you to complete the workout.

- Outcome-Based Programs ∞ This is the most clinically specific type of program. It requires you to achieve a particular health outcome. Often, this involves meeting targets for biometric screenings, such as attaining a certain blood pressure, cholesterol level, or body mass index (BMI). If you are a smoker, an outcome-based program would reward you for quitting, verified by testing, rather than just for attending a smoking cessation class.

Because these programs tie financial rewards directly to health factors, they are governed by a strict set of five criteria under the ACA and HIPAA to be considered nondiscriminatory. These rules are designed to protect individuals for whom achieving these outcomes may be difficult or medically inadvisable due to an underlying health condition. This is where the law begins to acknowledge the reality of biological diversity and the necessity of personalized health approaches.

Intermediate

The distinction between participatory and health-contingent wellness programs becomes clinically and legally meaningful when we examine the specific regulations designed to prevent discrimination and protect sensitive information. While participatory programs operate under a light touch, health-contingent programs are subject to a rigorous five-part test under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and HIPAA.

This test is a direct acknowledgment that when financial incentives are tied to health markers, a robust framework is required to ensure fairness and protect vulnerable individuals.

The Five Pillars of Nondiscriminatory Health-Contingent Programs

For a health-contingent program to be legally compliant, it must be “reasonably designed” to promote health or prevent disease. This standard is met by adhering to five specific requirements. These pillars create a structure that balances an employer’s goal of fostering a healthier workforce with an individual’s right to fair treatment, regardless of their starting health status.

- Annual Opportunity to Qualify ∞ The program must give every eligible individual a chance to qualify for the reward at least once per year. This provision ensures that wellness is not a one-time test but an ongoing process. From a physiological perspective, this aligns with the body’s dynamic nature; metabolic markers and health status can change over time with sustained effort, and the program must provide a recurring opportunity to demonstrate that progress.

- Limitation on Reward Size ∞ The total reward offered across all health-contingent programs generally cannot exceed 30% of the total cost of employee-only health coverage. This can be increased to 50% for programs designed to prevent or reduce tobacco use. This financial cap is a critical safeguard against coercion. It ensures the incentive is a motivational tool, preventing the penalty for non-participation from becoming so severe that it effectively forces employees to disclose protected health information or undergo medical testing against their will.

- Reasonable Design ∞ The program must have a reasonable chance of improving health or preventing disease, and it must not be overly burdensome. This principle prevents the implementation of arbitrary or scientifically unsupported goals. A program based on debunked health fads, for instance, would fail this test. It must be grounded in established medical understanding.

- Uniform Availability and Reasonable Alternatives ∞ This is arguably the most important pillar from a clinical and ethical standpoint. The full reward must be available to all similarly situated individuals. For those individuals for whom it is medically inadvisable or unreasonably difficult to meet the specified health standard, the program must offer a “reasonable alternative standard” (or a waiver of the standard). This is where the law directly confronts the reality of individual biology.

- Notice of Other Means ∞ The plan must disclose the availability of a reasonable alternative standard in all materials that describe the terms of a health-contingent wellness program. This transparency ensures that individuals are aware of their rights and can advocate for themselves if the primary standard is not appropriate for their health status.

What Constitutes a Reasonable Alternative Standard?

The concept of a reasonable alternative is where the legal framework demonstrates its deepest understanding of human physiology. It acknowledges that a single, uniform biometric target is inherently inequitable. A 55-year-old perimenopausal woman experiencing metabolic shifts, a 45-year-old man with clinically low testosterone affecting body composition, and a 30-year-old with a genetic predisposition to high cholesterol do not begin at the same physiological starting line. Penalizing them for failing to meet a generic “healthy” target would be discriminatory.

A reasonable alternative must be tailored to the individual’s condition. For an outcome-based program that rewards a specific BMI, a reasonable alternative for an individual for whom weight loss is difficult might be to meet a different goal, such as participating in a certain number of sessions with a registered dietitian or following a medically-approved exercise plan. The alternative shifts the focus from a potentially unattainable outcome to a constructive, health-promoting process.

The legal mandate for a reasonable alternative standard is the mechanism that allows wellness programs to accommodate, rather than penalize, biological individuality.

The table below clarifies the core legal distinctions that arise from these protective frameworks.

| Legal Provision | Participatory Program | Health-Contingent Program |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA/ACA Nondiscrimination | Must be available to all similarly situated individuals. No other requirements. | Must satisfy all five nondiscrimination requirements (annual opportunity, reward limits, reasonable design, reasonable alternatives, and notice). |

| Reward Limit | No federally mandated limit under HIPAA/ACA (though other laws may apply). | Generally limited to 30% of the cost of self-only coverage (50% for tobacco programs). |

| Reasonable Alternative Standard | Not required. | Required for any individual for whom it is unreasonably difficult or medically inadvisable to meet the standard. |

| Risk of Discrimination | Low. The focus is on universal participation. | High. The focus on outcomes necessitates strict legal safeguards to prevent discrimination based on health factors. |

These regulations transform a wellness program from a simple corporate perk into a regulated component of health benefits, governed by principles of fairness, privacy, and medical validity.

Academic

The legal architecture governing workplace wellness programs represents a complex intersection of public health policy, labor law, and civil rights. Beyond the foundational nondiscrimination rules of HIPAA and the ACA, two other federal statutes introduce profound layers of protection that speak directly to the core tenets of personalized medicine and biological individuality ∞ the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA).

These laws shift the analysis from preventing health-status discrimination in a general sense to protecting individuals with specific medical conditions and genetic predispositions.

The Role of the Americans with Disabilities Act

The ADA’s application to wellness programs is centered on the concept of a “medical examination.” When a wellness program requires employees to undergo biometric screenings (measuring blood pressure, cholesterol, or glucose) or complete a Health Risk Assessment (HRA), it is conducting a medical examination and making disability-related inquiries. Under the ADA, such exams must be “voluntary.”

The definition of “voluntary” has been a subject of intense regulatory debate. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which enforces the ADA, has historically taken a more stringent view than the agencies governing HIPAA. The core of the issue is whether a significant financial incentive ∞ even one permitted under the ACA’s 30% rule ∞ is so large that it becomes coercive, thus rendering participation involuntary.

A 2021 EEOC proposed rule suggested that for a wellness program to be considered truly voluntary under the ADA and GINA, any incentive offered must be “de minimis,” or minimal. This highlights a fundamental tension between the ACA’s goal of using substantial incentives to drive health improvements and the ADA’s goal of protecting employees from being pressured into revealing medical information.

This legal tension has direct physiological relevance. Many conditions that make it difficult to meet wellness program targets, such as diabetes, severe obesity, or even the metabolic syndrome that often accompanies endocrine disorders like Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) or hypogonadism, can be classified as disabilities under the ADA.

The ADA’s requirement for “reasonable accommodations” for individuals with disabilities functions as a powerful parallel to the ACA’s “reasonable alternative standard.” An employer who fails to provide a reasonable alternative for an employee with a diagnosed metabolic disorder may violate not only HIPAA/ACA rules but also the ADA by failing to provide a reasonable accommodation.

How Does GINA Reshape Program Boundaries?

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) provides a critical firewall protecting an individual’s most fundamental biological data. GINA prohibits employers from using genetic information in employment decisions and strictly limits their ability to acquire this information. In the context of wellness programs, “genetic information” is defined broadly. It includes not only the results of a genetic test but also an individual’s family medical history.

Therefore, a standard HRA that asks questions about whether a parent or sibling has had heart disease, cancer, or diabetes is collecting genetic information. Under GINA, an employer cannot offer any financial incentive in exchange for this information.

An employee can be asked to complete an HRA with such questions only if the questions are clearly identified as optional and no reward is tied to answering them. This creates a protective bubble around family history, recognizing it as a form of genetic data that could be used to discriminate.

GINA’s protections ensure that wellness programs focus on an individual’s present health status and behaviors, not on immutable genetic predispositions inherited from their family line.

The table below presents a comparative analysis of how these four key laws regulate wellness program design, illustrating the multi-layered compliance environment.

| Legal Framework | Primary Focus | Key Requirement for Wellness Programs | Protects Against |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIPAA / ACA | Nondiscrimination within group health plans. | Health-contingent programs must be reasonably designed and offer reasonable alternatives. | Charging individuals different premiums based on a health factor, without providing a fair chance to qualify. |

| ADA | Nondiscrimination against individuals with disabilities. | Medical exams (biometric screenings, HRAs) must be “voluntary.” Requires reasonable accommodations. | Forcing employees to disclose disability-related information or penalizing them for health outcomes linked to a disability. |

| GINA | Nondiscrimination based on genetic information. | Prohibits incentives for providing genetic information, including family medical history. | Employers acquiring or using information about genetic predispositions for disease. |

This complex interplay of regulations creates a system of checks and balances. A program design that is permissible under the ACA’s 30% incentive rule might be deemed involuntary under the ADA’s stricter standard. A seemingly innocuous HRA question about family history is permissible under HIPAA but heavily restricted by GINA.

Navigating this landscape requires a sophisticated understanding that moves beyond simple compliance with one statute to a holistic integration of all relevant legal and ethical principles, ultimately in service of protecting the employee’s sensitive health information and right to self-determination.

References

- U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Final Rules for Wellness Programs.” Federal Register, vol. 78, no. 106, 3 June 2013, pp. 33158-33207.

- Keith, Katie. “EEOC Issues Proposed Wellness Rules Under ADA And GINA.” Health Affairs, 12 Jan. 2021.

- Salo, Sarah. “Workplace Wellness Plan Design ∞ Legal Issues.” Apex Benefits, 2022.

- “Guide to Understanding Wellness Programs and their Legal Requirements.” Acadia Benefits, 2023.

- “Workplace Wellness Programs Characteristics and Requirements.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 19 May 2016.

- “HIPAA and the Affordable Care Act Wellness Program Requirements.” U.S. Department of Labor, Employee Benefits Security Administration, 2013.

- “Workplace Wellness Plans Are Not So Well.” The National Law Review, vol. XII, no. 230, 17 Aug. 2022.

Reflection

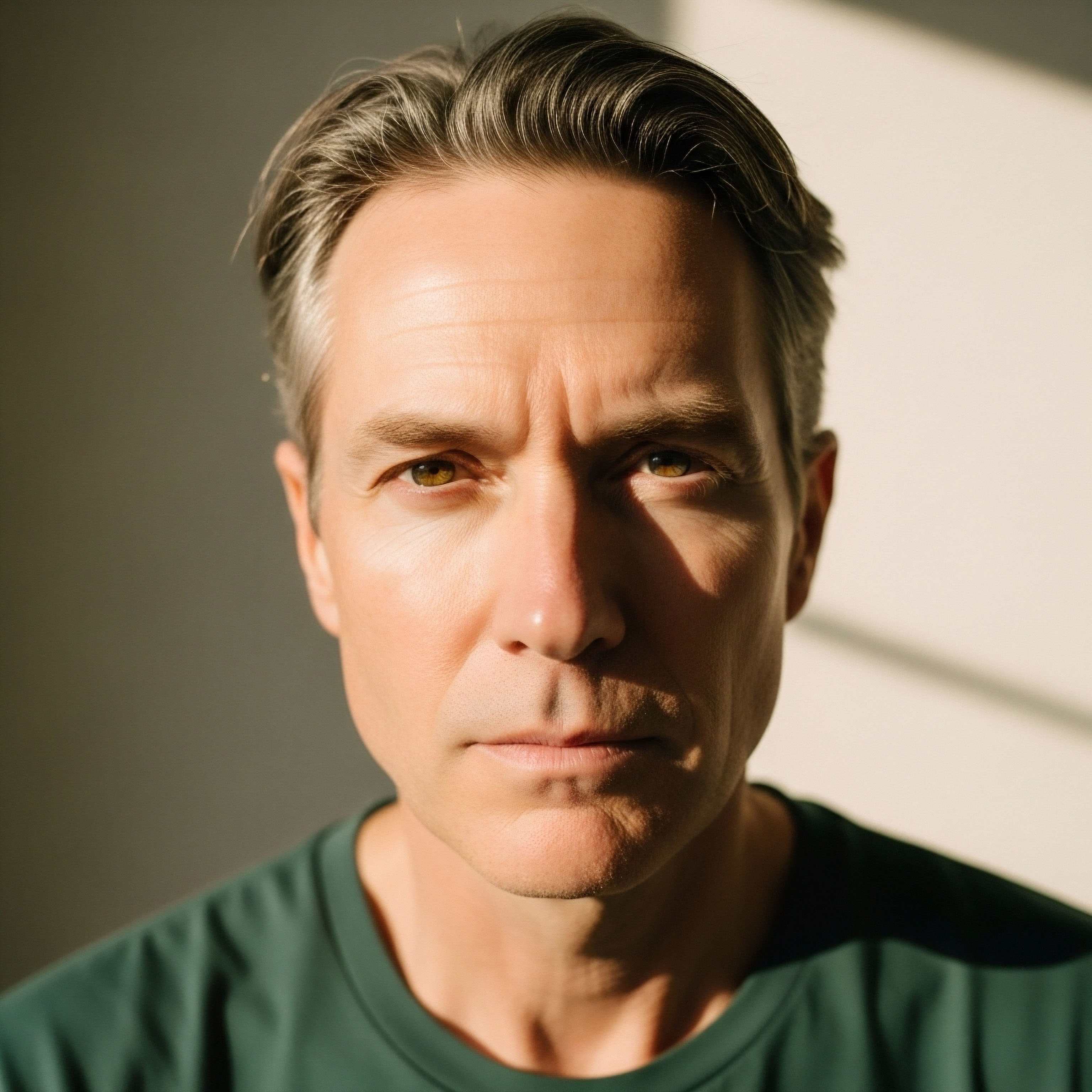

Calibrating Your Personal Health Equation

You have now seen the intricate legal machinery that operates behind the curtain of workplace wellness. This knowledge serves a purpose far beyond academic understanding. It equips you to view these programs through a new lens, one calibrated to your own unique biology and personal health objectives. The language of “reasonable alternatives” and “voluntary participation” is more than legal jargon; it is an affirmation that your individual health context matters.

Consider the wellness initiatives you have encountered in your own life. How were they structured? Did they invite participation or demand outcomes? Did they feel like an opportunity for empowerment or a source of pressure? Your answers to these questions reveal the intent behind their design. The architecture of these programs speaks volumes about whether they are built to accommodate the complex, dynamic reality of human physiology or to simply enforce a static, one-size-fits-all definition of health.

The path to sustained vitality is a deeply personal one, guided by your own data, your lived experience, and your specific goals. The legal frameworks are in place to protect your right to walk that path. The ultimate responsibility, and the ultimate opportunity, resides with you to use this knowledge, to ask informed questions, and to advocate for a wellness paradigm that respects the integrity of your individual health journey.