Fundamentals

You may be here because something feels off. Perhaps it’s a subtle shift in your energy, a change in your mood, or a noticeable difference in your physical performance. These experiences are valid, and they often have a biological basis.

Your body communicates through an intricate language of chemical messengers, and understanding this language is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. The regulation of male reproduction is a testament to this elegant biological communication, a system designed for resilience and function. Let’s explore the key hormones that govern this system, not as abstract concepts, but as vital components of your personal health narrative.

The Command Center the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

Your body’s hormonal systems are organized in a hierarchical structure. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the primary regulatory pathway for male reproductive health. This axis is a dynamic communication loop between your brain and your testes, ensuring a steady and appropriate level of hormones to maintain various bodily functions. The process begins in the hypothalamus, a small but powerful region in your brain that acts as the master controller.

The hypothalamus releases a crucial hormone called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). GnRH is released in a pulsatile manner, like a carefully timed drumbeat, which is essential for its proper function. This rhythmic release of GnRH travels to the pituitary gland, another key player located at the base of your brain. The pituitary gland, in response to GnRH, releases two other important hormones into your bloodstream ∞ Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

The HPG axis is a finely tuned feedback system that connects the brain to the gonads, orchestrating male reproductive function through a cascade of hormonal signals.

The Key Players Luteinizing Hormone and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) are known as gonadotropins because they act on the gonads, which in males are the testes. These two hormones have distinct yet complementary roles in male reproductive health.

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) travels through your bloodstream to the testes, where it stimulates specialized cells called Leydig cells to produce testosterone. Think of LH as the direct signal for testosterone production. When LH levels are optimal, your body can produce adequate amounts of testosterone.

- Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) also acts on the testes, but its primary role is to support sperm production, a process called spermatogenesis. FSH stimulates the Sertoli cells in the testes, which are responsible for nourishing and supporting developing sperm cells.

The coordinated action of LH and FSH ensures both the production of testosterone and the maintenance of fertility. An imbalance in either of these hormones can have significant consequences for your overall health and well-being.

Testosterone the Architect of Masculinity

Testosterone is arguably the most well-known male hormone, and for good reason. It is the primary male androgen and plays a central role in a wide range of physiological processes. Produced primarily in the testes, testosterone is responsible for the development of male secondary sexual characteristics during puberty, such as a deepening voice, facial and body hair growth, and increased muscle mass.

Beyond its role in development, testosterone is essential for maintaining ∞

- Sexual Function ∞ Testosterone drives libido (sex drive) and is involved in achieving and maintaining erections.

- Muscle Mass and Strength ∞ It promotes protein synthesis, which is crucial for building and maintaining muscle tissue.

- Bone Density ∞ Testosterone helps maintain strong and healthy bones, reducing the risk of osteoporosis later in life.

- Red Blood Cell Production ∞ It stimulates the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow, which carry oxygen throughout your body.

- Mood and Cognitive Function ∞ Testosterone can influence mood, focus, and overall mental clarity.

The effects of testosterone are systemic, touching nearly every aspect of your physical and mental health. When testosterone levels decline, you may experience a range of symptoms that can significantly impact your quality of life. Understanding the role of this powerful hormone is fundamental to understanding your own body.

Intermediate

Having a foundational understanding of the key hormones involved in male reproduction allows us to delve deeper into the clinical applications of this knowledge. When the delicate balance of the HPG axis is disrupted, it can lead to a condition known as hypogonadism, or low testosterone.

This section will explore the protocols used to address this condition, moving from diagnosis to treatment and monitoring. We will examine how these interventions are designed to restore hormonal balance and improve your quality of life.

Diagnosing Hypogonadism a Matter of Precision

A diagnosis of hypogonadism is established through a combination of clinical symptoms and laboratory testing. The symptoms of low testosterone can be non-specific and may include fatigue, low libido, erectile dysfunction, depression, and a decline in physical performance. Because these symptoms can have multiple causes, objective laboratory measurements are essential for an accurate diagnosis.

Blood tests are used to measure your serum testosterone levels. It is important that these tests are conducted in the morning, as testosterone levels naturally peak at this time. A diagnosis of hypogonadism is typically confirmed when a man has consistently low testosterone levels (usually below 300 ng/dL) on at least two separate occasions, in conjunction with relevant symptoms. In addition to total testosterone, a comprehensive evaluation will often include measurements of:

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) ∞ These levels help determine if the hypogonadism is primary (a problem with the testes) or secondary (a problem with the pituitary or hypothalamus).

- Prolactin ∞ Elevated prolactin levels can suppress testosterone production.

- Estradiol ∞ The balance between testosterone and estrogen is important for male health.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) ∞ To check for anemia and red blood cell count.

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) ∞ As a baseline before considering testosterone therapy.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy Protocols

Once a diagnosis of hypogonadism is confirmed, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) may be considered. The goal of TRT is to restore testosterone levels to a healthy physiological range, thereby alleviating symptoms and improving overall well-being. There are several methods of administering testosterone, each with its own set of advantages and considerations.

| Method | Description | Typical Dosing | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular Injections | Testosterone cypionate or enanthate is injected into a muscle. | 50-100mg weekly or 100-200mg every two weeks. | Cost-effective and provides stable levels with frequent injections. May cause fluctuations in mood and energy if injections are spaced too far apart. |

| Subcutaneous Injections | Testosterone is injected into the fatty tissue under the skin. | Smaller, more frequent doses (e.g. 2x/week) can provide very stable levels. | Minimizes peaks and troughs in testosterone levels. Some individuals may experience localized skin reactions. |

| Topical Gels/Creams | A gel or cream containing testosterone is applied to the skin daily. | 50-100mg of testosterone daily. | Provides stable daily levels. Risk of transference to others through skin contact. |

| Pellet Therapy | Small testosterone pellets are implanted under the skin. | 150-450mg implanted every 3-6 months. | Convenient, long-acting option. Requires a minor surgical procedure for implantation and removal. |

Ancillary Medications the Importance of a Comprehensive Approach

A well-managed TRT protocol often includes ancillary medications to optimize results and mitigate potential side effects. These medications are not a one-size-fits-all solution and are prescribed based on an individual’s specific needs and lab results.

- Gonadorelin ∞ This is a GnRH analogue. When a man is on TRT, his body’s natural production of LH and FSH is suppressed. Gonadorelin can be used to mimic the body’s natural GnRH pulses, thereby stimulating the pituitary to produce LH and FSH. This helps to maintain testicular size and function, and can also preserve fertility. It is often administered as a subcutaneous injection twice a week.

- Anastrozole ∞ This is an aromatase inhibitor. Testosterone can be converted into estradiol (a form of estrogen) by an enzyme called aromatase. In some men on TRT, this conversion can lead to elevated estrogen levels, which can cause side effects like water retention, gynecomastia (breast tissue development), and mood swings. Anastrozole blocks the aromatase enzyme, thus reducing the conversion of testosterone to estrogen. It is typically taken as an oral tablet twice a week.

- Enclomiphene ∞ This is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Enclomiphene works by blocking estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. This tricks the brain into thinking that estrogen levels are low, which in turn leads to an increase in GnRH, LH, and FSH production. This can be used as an alternative to TRT for some men with secondary hypogonadism, or as part of a post-TRT protocol to restart the body’s natural testosterone production.

Post-TRT and Fertility-Stimulating Protocols

For men who wish to discontinue TRT or for those who are trying to conceive, a specific protocol is needed to restart the HPG axis. Abruptly stopping TRT can lead to a significant crash in hormone levels and a return of hypogonadal symptoms. A post-TRT protocol is designed to stimulate the body’s own production of testosterone and sperm.

These protocols often include a combination of medications such as:

- Gonadorelin ∞ To stimulate the pituitary gland.

- Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) or Enclomiphene ∞ To block estrogen receptors and boost LH and FSH production.

- Tamoxifen (Nolvadex) ∞ Another SERM that can be used to stimulate the HPG axis.

- Anastrozole ∞ To control estrogen levels, which can rise as testosterone production restarts.

The specific combination and dosage of these medications will depend on the individual’s response and lab work. The goal is to carefully guide the body back to a state of hormonal self-sufficiency.

Academic

The regulation of male reproduction is a sophisticated process that extends beyond the classical HPG axis. A deeper, academic exploration reveals a complex network of neuroendocrine signals, metabolic inputs, and genetic factors that modulate reproductive function. This section will delve into the neuroendocrine control of male reproduction, focusing on the pulsatile nature of GnRH secretion and the emerging role of neuropeptides like kisspeptin.

We will also examine the intricate relationship between metabolic health and the HPG axis, highlighting the systemic nature of hormonal regulation.

The Pulsatile Nature of GnRH and Its Differential Control of Gonadotropins

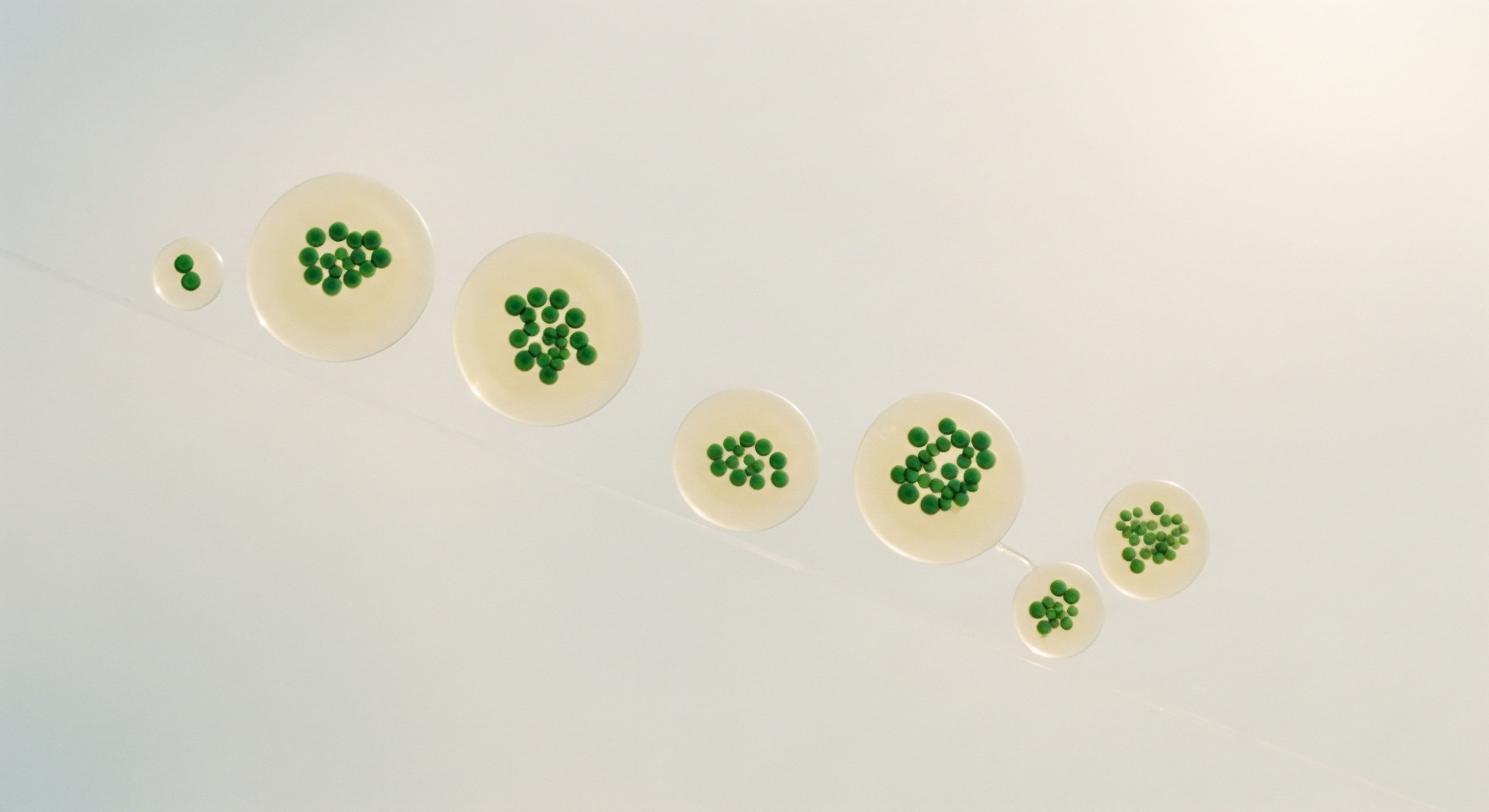

The secretion of GnRH from the hypothalamus is not a continuous stream but rather a series of discrete pulses. This pulsatility is a critical feature of the neuroendocrine control of reproduction. The frequency and amplitude of GnRH pulses determine the differential secretion of LH and FSH from the pituitary gland.

Generally, higher frequency GnRH pulses favor LH secretion, while lower frequency pulses favor FSH secretion. This differential regulation allows for a fine-tuning of testicular function, independently modulating testosterone production and spermatogenesis.

The GnRH pulse generator, a network of neurons in the hypothalamus, is influenced by a variety of internal and external cues, including stress, nutritional status, and circadian rhythms. The intricate mechanisms that govern this pulsatility are an active area of research, with significant implications for understanding and treating reproductive disorders.

The pulsatile secretion of GnRH is a fundamental principle of reproductive neuroendocrinology, enabling the differential regulation of LH and FSH and the precise control of testicular function.

Kisspeptin the Gatekeeper of Puberty and Reproduction

In recent years, the neuropeptide kisspeptin has emerged as a master regulator of the HPG axis. Kisspeptin, and its receptor, GPR54, are now understood to be essential for the onset of puberty and the maintenance of reproductive function in adulthood. Kisspeptin neurons are located in specific regions of the hypothalamus and they directly stimulate GnRH neurons to release GnRH.

The discovery of kisspeptin has revolutionized our understanding of reproductive neuroendocrinology. It provides a crucial link between the higher brain centers that process metabolic and environmental information and the GnRH neurons that drive the HPG axis. For instance, kisspeptin neurons are sensitive to sex steroids, forming a key part of the negative feedback loop that regulates testosterone production. They are also influenced by metabolic hormones like leptin, providing a mechanism by which the body’s energy status can modulate reproductive function.

The Interplay between Metabolic Health and the HPG Axis

The HPG axis does not operate in isolation. There is a profound and bidirectional relationship between metabolic health and reproductive function. Conditions such as obesity and metabolic syndrome are strongly associated with secondary hypogonadism in men. This connection is mediated by several factors:

- Insulin Resistance ∞ Insulin resistance, a hallmark of metabolic syndrome, can impair pituitary and testicular function, leading to reduced testosterone levels.

- Leptin ∞ Leptin is a hormone produced by fat cells that signals satiety to the brain. While leptin is necessary for normal reproductive function, excessive levels of leptin, as seen in obesity, can lead to leptin resistance, which can disrupt GnRH pulsatility.

- Inflammation ∞ Obesity is associated with a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Inflammatory cytokines can suppress the HPG axis at multiple levels, from the hypothalamus to the testes.

- Aromatase Activity ∞ Adipose tissue (body fat) is a major site of aromatase activity, the enzyme that converts testosterone to estrogen. Increased body fat can lead to higher estrogen levels, which can further suppress the HPG axis through negative feedback.

This intricate interplay underscores the importance of a holistic approach to male hormonal health. Addressing underlying metabolic issues is often a critical step in restoring normal HPG axis function.

| Modulator | Source | Primary Action on HPG Axis | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kisspeptin | Hypothalamic neurons | Stimulates GnRH release | Essential for puberty and fertility. A potential therapeutic target for reproductive disorders. |

| Leptin | Adipose tissue | Permissive role in GnRH secretion | Links energy status to reproductive function. Leptin deficiency or resistance can cause hypogonadism. |

| Ghrelin | Stomach | Inhibits GnRH secretion | Signals hunger and can suppress reproductive function during periods of negative energy balance. |

| Endogenous Opioids | Central Nervous System, Testis | Inhibit GnRH release | Mediate stress-induced reproductive suppression. Opioid use can cause hypogonadism. |

What Are the Genetic Underpinnings of Male Hypogonadism?

While lifestyle and environmental factors play a significant role in male reproductive health, there is also a genetic component to many forms of hypogonadism. Mutations in genes that code for hormones, their receptors, or the enzymes involved in their synthesis can lead to congenital reproductive disorders.

For example, Kallmann syndrome is a genetic disorder characterized by hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and an impaired sense of smell, caused by mutations that affect the migration of GnRH neurons during fetal development. Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) is another genetic condition that leads to primary hypogonadism. Advances in genetic sequencing are providing new insights into the molecular basis of male infertility and hypogonadism, paving the way for more personalized diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the future.

References

- Bhasin, S. et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

- Rochira, V. et al. “Physiology of the Hypothalamic Pituitary Gonadal Axis in the Male.” Urologic Clinics of North America, vol. 43, no. 2, 2016, pp. 151-62.

- Morley, J. E. “Testosterone Treatment and Mortality.” Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, vol. 45, no. 1, 2016, pp. 135-46.

- Tsutsumi, R. and Webster, N. J. G. “GnRH pulsatility, the pituitary response and reproductive dysfunction.” Endocrine Journal, vol. 56, no. 6, 2009, pp. 729-37.

- Fain, J. N. “Release of inflammatory mediators by human adipose tissue is enhanced in obesity and primarily by the nonfat cells.” Vitamins and Hormones, vol. 80, 2009, pp. 445-56.

- Tajar, A. et al. “Characteristics of secondary, primary, and compensated hypogonadism in aging men ∞ evidence from the European Male Ageing Study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 95, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1810-18.

- Kim, E. D. et al. “Oral enclomiphene citrate raises testosterone and preserves sperm counts in obese hypogonadal men, unlike topical testosterone.” BJU International, vol. 117, no. 4, 2016, pp. 677-85.

- Dufour, S. et al. “Origin and evolution of the neuroendocrine control of reproduction in vertebrates.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, vol. 295, no. 2, 2008, pp. R358-75.

- Rastrelli, G. et al. “Testosterone and benign prostatic hyperplasia.” Sexual Medicine Reviews, vol. 7, no. 2, 2019, pp. 259-71.

- Snyder, P. J. et al. “Effects of Testosterone Treatment in Older Men.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 374, no. 7, 2016, pp. 611-24.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the intricate world of male hormonal health, from the foundational principles of the HPG axis to the clinical nuances of hormone optimization. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It allows you to move from a place of uncertainty to one of understanding.

Your personal health story is unique, and the information presented here is a map, not a destination. The next step in your journey is to reflect on how this information resonates with your own experiences. What questions has it raised for you? What possibilities does it open up?

Your biology is not your destiny; it is your biography, and you are the author of the next chapter. This understanding is the beginning of a new conversation with your body, one that is informed, empowered, and proactive.