Fundamentals

Many individuals experience subtle shifts in their well-being, a feeling that something is simply “off,” yet traditional explanations often fall short. Perhaps you have noticed persistent fatigue, unexplained mood fluctuations, or a general sense of diminished vitality. These experiences are not merely subjective; they frequently signal deeper, interconnected processes within your biological systems.

Understanding your body’s intricate messaging network, particularly the role of hormones and how they are processed, offers a path toward reclaiming optimal function. Your personal journey toward vitality begins with recognizing these subtle cues and seeking a deeper understanding of their origins.

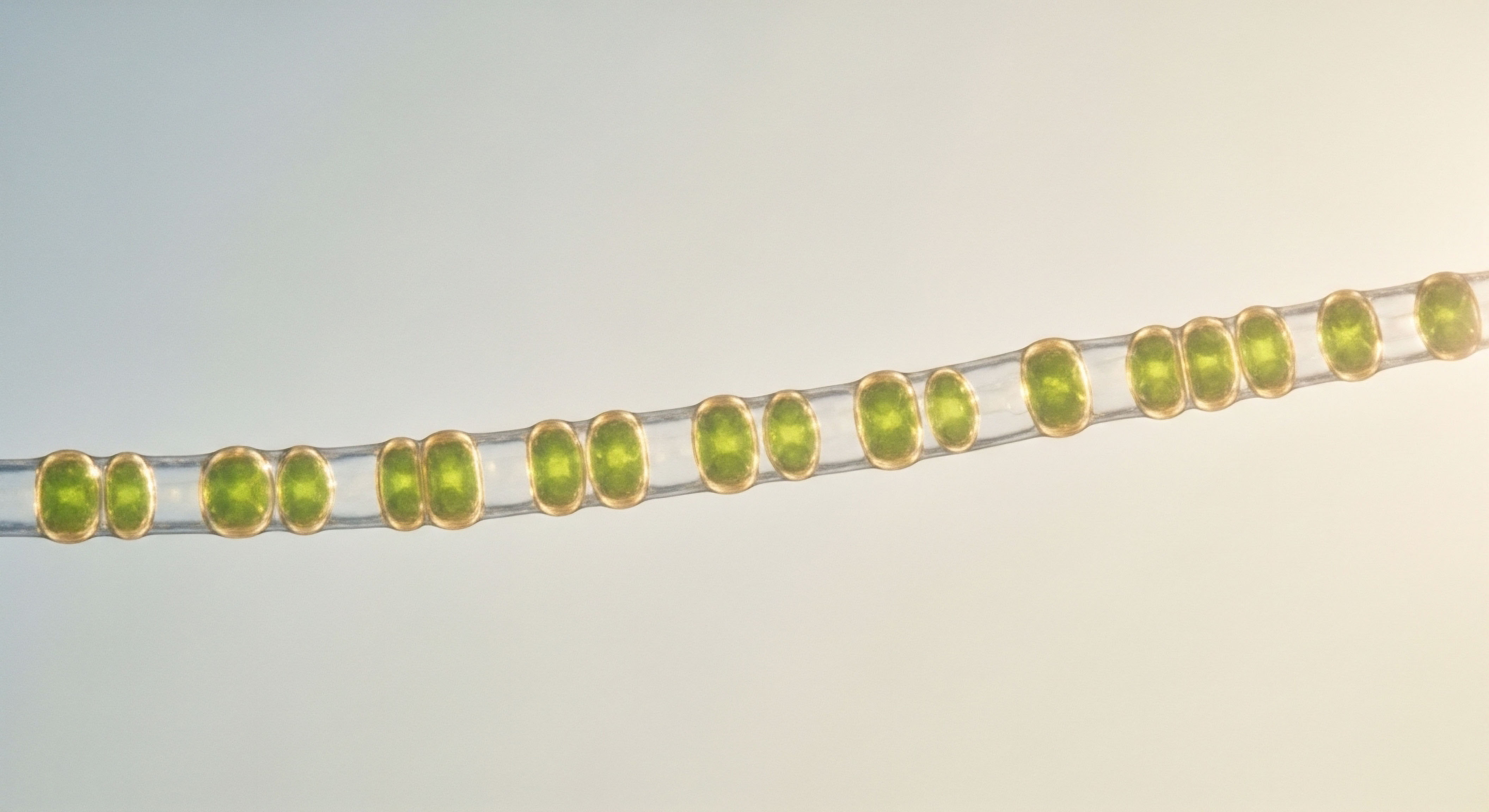

The liver, a remarkable organ, acts as the body’s central processing unit, performing hundreds of vital functions. Among its many responsibilities, the liver plays a paramount role in managing the body’s hormonal landscape. It acts as a sophisticated detoxification and metabolic hub, constantly working to break down and eliminate substances, including the very hormones that regulate your daily functions.

This metabolic activity involves a complex array of specialized proteins known as hepatic enzymes. These enzymes are the molecular machinery responsible for transforming hormones, preparing them for excretion, or converting them into other active or inactive forms.

Sex steroids, such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, are powerful chemical messengers that orchestrate a vast array of physiological processes. They influence everything from mood and energy levels to muscle mass and bone density. These hormones do not simply circulate indefinitely; they undergo a precise cycle of synthesis, action, and eventual breakdown.

The liver is a primary site for this breakdown, ensuring that hormone levels remain within a healthy range and that their signals are appropriately managed. When this delicate balance is disrupted, either by an excess or deficiency of hormones, or by inefficiencies in their processing, symptoms can arise that significantly impact your quality of life.

The liver serves as a central metabolic hub, crucial for processing and eliminating the body’s powerful sex steroid hormones.

The modulation of hepatic enzymes by sex steroids refers to the dynamic interaction where these hormones can either increase or decrease the activity of specific liver enzymes. This interaction is not a one-way street; it is a reciprocal relationship. Hormones influence the enzymes, and the enzymes, in turn, influence the hormones.

This intricate dance determines how long hormones remain active in the body, how they are converted, and ultimately, their biological impact. Variations in this process can explain why two individuals with similar hormone levels might experience different symptoms or respond differently to hormonal support protocols.

Consider the impact of this modulation on your overall well-being. If certain enzymes are overactive, they might clear hormones too quickly, leading to a functional deficiency even if production is adequate. Conversely, if enzymes are underactive, hormones might linger longer than desired, potentially leading to symptoms associated with excess.

This understanding moves beyond simply measuring hormone levels in the blood; it prompts a deeper consideration of how your body handles these vital compounds once they are released. It is about understanding the entire lifecycle of a hormone within your system.

The Liver’s Role in Hormone Processing

The liver’s capacity to process hormones is foundational to endocrine health. It houses a sophisticated system of enzymes, primarily the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, which are responsible for the initial phase of hormone metabolism. These enzymes act like specialized chemical scissors, modifying the hormone’s structure to make it more water-soluble, a necessary step for its eventual removal from the body.

This initial modification is often followed by a second phase, where other enzymes attach molecules like glucuronic acid or sulfate to the hormone, further preparing it for excretion via bile or urine.

Each sex steroid has a unique metabolic pathway within the liver. For instance, testosterone can be converted into other active forms, such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT), or into estrogens, like estradiol, through the action of the aromatase enzyme, which is also present in the liver.

Estrogens themselves undergo a series of hydroxylation reactions, leading to different estrogen metabolites, some of which are considered more favorable than others for long-term health. Progesterone also has its own metabolic routes, influencing its half-life and biological effects.

Understanding these pathways provides insight into why personalized wellness protocols are so important. Genetic variations, dietary factors, environmental exposures, and even stress levels can all influence the activity of these hepatic enzymes. This means that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to hormonal balance rarely yields optimal results. Instead, a tailored strategy that considers your unique metabolic profile is essential for restoring vitality and function without compromise.

Intermediate

The liver’s metabolic capacity directly influences the efficacy and safety of hormonal optimization protocols. When we introduce exogenous hormones, such as in testosterone replacement therapy, or utilize peptides to modulate endogenous hormone production, the liver’s enzymatic machinery becomes a central player in determining how these compounds are processed, distributed, and ultimately cleared from the body.

This section explores the specific clinical protocols and their interactions with hepatic enzyme systems, providing a deeper understanding of the ‘how’ and ‘why’ behind therapeutic strategies.

Consider the administration of testosterone cypionate in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy (TRT). Once injected, this esterified form of testosterone is gradually released into the bloodstream. The liver then plays a significant role in its metabolism. Hepatic enzymes, particularly various CYP isoforms, are responsible for breaking down testosterone into its metabolites, including inactive forms and those that can be converted into estrogens.

The rate at which these enzymes function can influence the steady-state levels of testosterone and its metabolites, affecting both therapeutic outcomes and potential side effects.

Liver enzyme activity profoundly shapes the effectiveness and safety profile of hormonal optimization strategies.

Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Hepatic Processing

For men receiving TRT, a standard protocol often involves weekly intramuscular injections of testosterone cypionate. This approach aims to restore physiological testosterone levels, addressing symptoms such as low energy, reduced libido, and diminished muscle mass. Alongside the testosterone, medications like gonadorelin are often prescribed.

Gonadorelin, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, stimulates the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), helping to maintain natural testosterone production and preserve fertility. Gonadorelin itself is a peptide that undergoes rapid enzymatic degradation, primarily by peptidases, ensuring its transient action.

Another key component in male TRT protocols is anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor. Aromatase, an enzyme present in various tissues including the liver, converts testosterone into estradiol. By inhibiting this enzyme, anastrozole helps to manage estrogen levels, preventing potential side effects associated with elevated estrogen, such as gynecomastia or water retention. The liver metabolizes anastrozole itself, primarily through N-dealkylation and glucuronidation, highlighting the liver’s continuous involvement in processing therapeutic agents.

For men who have discontinued TRT or are seeking to conceive, a post-TRT or fertility-stimulating protocol is often implemented. This typically includes a combination of agents designed to reactivate the body’s natural testosterone production.

Tamoxifen and clomid (clomiphene citrate) are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) that act at the pituitary gland to increase LH and FSH secretion, thereby stimulating testicular testosterone production. Both tamoxifen and clomiphene undergo extensive hepatic metabolism, with various CYP enzymes playing roles in their activation and inactivation. Understanding these metabolic pathways is vital for predicting individual responses and managing potential drug interactions.

Hormonal Balance for Women and Liver Function

Women also benefit from targeted hormonal support, particularly during peri-menopause and post-menopause, or when experiencing symptoms of low testosterone. Protocols for women often involve lower doses of testosterone cypionate, typically administered weekly via subcutaneous injection. The liver’s role in metabolizing this testosterone is similar to that in men, influencing the balance between testosterone and its estrogenic metabolites.

Progesterone is another essential hormone for female balance, prescribed based on menopausal status. Oral progesterone undergoes significant first-pass metabolism in the liver, meaning a large portion of the dose is metabolized before it reaches systemic circulation. This hepatic processing generates various progesterone metabolites, some of which have sedative properties, explaining why oral progesterone is often taken at night.

The specific enzymes involved in progesterone metabolism, primarily CYP3A4, can be influenced by other medications or dietary factors, impacting its bioavailability and effects.

Pellet therapy, offering long-acting testosterone delivery, is another option for women. While pellets bypass the initial first-pass liver metabolism of oral forms, the circulating testosterone is still subject to hepatic enzymatic breakdown and conversion, requiring careful monitoring of hormone levels and symptom response. Anastrozole may also be used in women when appropriate, particularly to manage estrogen levels if conversion from testosterone is excessive.

| Hormonal Agent | Primary Hepatic Enzyme Involvement | Clinical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Testosterone Cypionate | CYP3A4, CYP2C9, Aromatase | Metabolism rate affects circulating levels and estrogen conversion. |

| Anastrozole | CYP3A4, Glucuronidation | Liver function influences drug clearance and efficacy in estrogen control. |

| Progesterone (Oral) | CYP3A4 | Significant first-pass metabolism impacts bioavailability and metabolite profile. |

| Tamoxifen / Clomiphene | CYP2D6, CYP3A4 | Genetic variations in these enzymes can alter drug activation and response. |

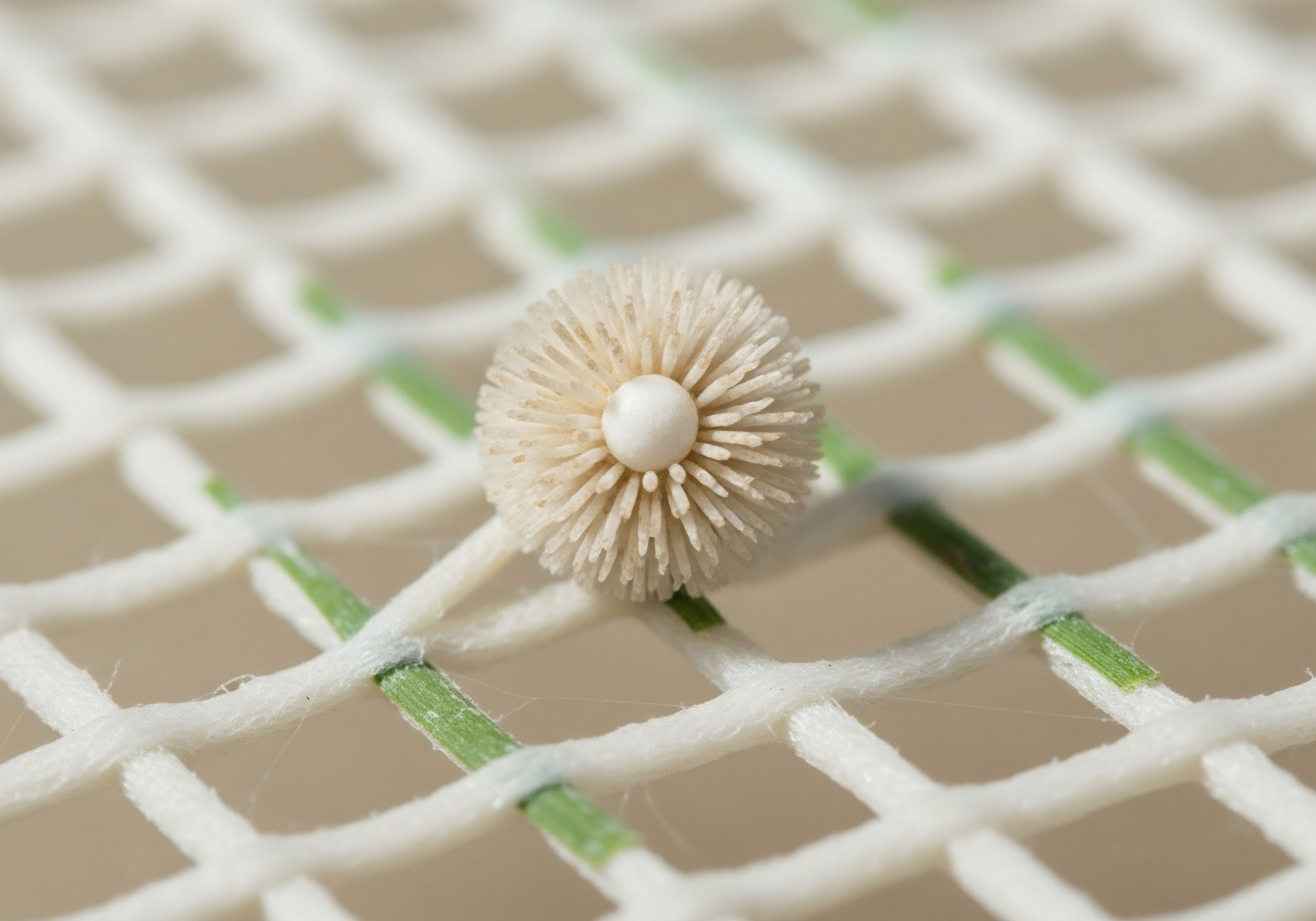

Peptide Therapies and Hepatic Modulation

Growth hormone peptide therapy, utilizing agents like sermorelin, ipamorelin / CJC-1295, and tesamorelin, represents another avenue for optimizing metabolic function and promoting vitality. These peptides stimulate the body’s natural production of growth hormone.

While peptides themselves are primarily broken down by peptidases throughout the body, including in the liver, their indirect effects on growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) can influence overall metabolic pathways that involve hepatic enzymes. For example, growth hormone can modulate the expression of certain CYP enzymes, adding another layer of complexity to the interconnectedness of these systems.

Other targeted peptides, such as PT-141 for sexual health or pentadeca arginate (PDA) for tissue repair, also interact with the body’s systems, and their metabolites are ultimately processed by the liver and kidneys.

While their direct impact on hepatic enzyme modulation may be less pronounced than that of sex steroids, the liver’s overarching role in clearing these compounds and their byproducts remains essential for maintaining systemic balance and therapeutic safety. A comprehensive understanding of these interactions allows for more precise and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Academic

The intricate relationship between sex steroids and hepatic enzyme modulation extends far beyond simple metabolism; it represents a sophisticated regulatory network that profoundly influences systemic physiology. This section delves into the molecular underpinnings of these interactions, exploring the specific enzyme systems involved, the mechanisms of their regulation, and the broader implications for metabolic health and clinical outcomes. Understanding these deep biological processes is essential for truly personalized wellness protocols.

The liver’s capacity to metabolize xenobiotics and endogenous compounds, including hormones, is largely attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily of enzymes. These heme-containing monooxygenases are primarily located in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes and are responsible for Phase I biotransformation reactions, which typically involve oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis.

Different CYP isoforms exhibit distinct substrate specificities, meaning they are responsible for metabolizing particular classes of compounds. The expression and activity of these CYP enzymes are highly variable among individuals, influenced by genetic polymorphisms, environmental factors, and, significantly, by hormonal status.

Sex steroids intricately regulate hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes, influencing their expression and activity at a molecular level.

Molecular Mechanisms of Enzyme Regulation

Sex steroids exert their modulatory effects on hepatic enzymes primarily through nuclear receptors. These receptors, such as the androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR), are ligand-activated transcription factors. Upon binding to their respective hormones, these receptors translocate to the nucleus, where they bind to specific DNA sequences in the promoter regions of target genes, thereby regulating gene expression. This transcriptional regulation can either upregulate (increase) or downregulate (decrease) the synthesis of specific CYP enzymes.

For instance, androgens, including testosterone, are known to influence the expression of several CYP enzymes. Studies have shown that testosterone can induce the expression of CYP3A4, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, and also affect other isoforms like CYP2C9 and CYP2C19.

This induction means that higher androgen levels might lead to faster metabolism of certain drugs or endogenous compounds that are substrates for these enzymes. Conversely, estrogens, acting through estrogen receptors, can also modulate CYP activity, often with isoform-specific effects. Estrogens have been observed to inhibit certain CYP enzymes while inducing others, contributing to the sex-dependent differences in drug metabolism observed in clinical practice.

The precise mechanisms involve complex signaling cascades. Beyond direct nuclear receptor activation, sex steroids can also influence enzyme activity through post-transcriptional modifications, such as protein stabilization or degradation, and through indirect effects on other regulatory pathways. This multi-layered regulation highlights the sophistication of the body’s homeostatic mechanisms.

Genetic Polymorphisms and Individual Variability

Individual responses to hormonal therapies and the metabolism of endogenous hormones are significantly influenced by genetic polymorphisms in CYP enzymes. These genetic variations, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), can alter the enzyme’s activity, leading to “poor metabolizer,” “intermediate metabolizer,” “extensive metabolizer,” or “ultrarapid metabolizer” phenotypes. For example, polymorphisms in CYP2D6 can dramatically affect the metabolism of tamoxifen, a key medication in post-TRT protocols, influencing its efficacy and the risk of side effects.

Understanding an individual’s genetic metabolic profile provides a powerful tool for personalizing therapeutic strategies. If a patient is an ultrarapid metabolizer of a particular enzyme, they might require higher doses of a medication to achieve therapeutic levels, or a different compound altogether. Conversely, a poor metabolizer might experience exaggerated effects or increased toxicity from standard doses. This level of precision moves beyond empirical dosing to a truly data-driven approach to hormonal optimization.

How Do Sex Steroids Influence Drug Metabolism Pathways?

The influence of sex steroids extends beyond their direct impact on hormone metabolism to affect the pharmacokinetics of numerous therapeutic agents. Many medications are metabolized by the same CYP enzymes that process sex hormones. This creates potential for drug-drug interactions where changes in sex steroid levels, either physiological or due to exogenous administration, can alter the metabolism of co-administered drugs.

For instance, if testosterone induces CYP3A4, it could potentially accelerate the clearance of other drugs metabolized by CYP3A4, reducing their effectiveness.

This interplay is particularly relevant in the context of personalized wellness protocols where multiple agents might be used concurrently. A comprehensive understanding of these interactions allows clinicians to anticipate potential issues and adjust dosages accordingly, ensuring both safety and efficacy. It underscores the need for careful monitoring of liver function and drug levels when implementing complex hormonal or peptide therapies.

Systems Biology Perspective on Hepatic Modulation

Viewing hepatic enzyme modulation by sex steroids through a systems-biology lens reveals its profound interconnectedness with other physiological axes. The liver is not merely a metabolic organ; it is an active participant in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, the central regulatory pathway for sex hormones.

Hepatic production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), for example, directly influences the bioavailability of circulating sex steroids. SHBG levels can be modulated by various factors, including thyroid hormones, insulin, and inflammatory cytokines, creating a complex web of interactions.

Moreover, the liver’s metabolic health, including conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), can significantly impact its enzymatic capacity and, consequently, hormone metabolism. Insulin resistance, a common metabolic dysfunction, can alter the expression of CYP enzymes and SHBG, further disrupting hormonal balance. This highlights that optimizing hormonal health requires a holistic approach that addresses underlying metabolic dysfunctions and systemic inflammation, not just isolated hormone levels.

| Enzyme Class | Primary Substrates (Sex Steroids) | Role in Metabolism |

|---|---|---|

| CYP3A4 | Testosterone, Estradiol, Progesterone | Major enzyme for Phase I hydroxylation and oxidation of sex steroids. |

| CYP2C9 | Testosterone, Estrogen metabolites | Involved in the metabolism of various steroids and xenobiotics. |

| CYP2D6 | Indirectly via drug metabolism (e.g. Tamoxifen) | Crucial for activating or inactivating many pharmaceutical agents. |

| Aromatase (CYP19A1) | Testosterone, Androstenedione | Converts androgens to estrogens; a key target in hormonal balance. |

| UGT (Uridine Glucuronosyltransferases) | Estrogens, Androgens, Progesterone metabolites | Phase II enzyme for glucuronidation, increasing water solubility for excretion. |

The interplay between sex steroids, hepatic enzymes, and overall metabolic function represents a dynamic equilibrium. Disruptions in this balance can contribute to a wide range of symptoms, from hormonal imbalances to impaired detoxification. A deep understanding of these molecular and systemic interactions empowers individuals and clinicians to design highly personalized interventions that address root causes, promoting sustained vitality and optimal physiological function. This precision approach moves beyond symptomatic relief to true biological recalibration.

References

- Speroff, Leon, and Marc A. Fritz. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. 8th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

- Boron, Walter F. and Emile L. Boulpaep. Medical Physiology ∞ A Cellular and Molecular Approach. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Katzung, Bertram G. Anthony J. Trevor, and Susan B. Masters. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 14th ed. McGraw-Hill Education, 2018.

- Waxman, David J. and Leslie D. Holloway. “Sex-dependent expression of liver cytochrome P450 enzymes ∞ regulation by growth hormone and sex steroids.” Molecular Pharmacology, vol. 78, no. 4, 2010, pp. 540-547.

- Nelson, David R. “Cytochrome P450 Nomenclature, 2004.” Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 320, 2006, pp. 1-10.

- Soldin, Offie P. and Daniel J. Soldin. “Sex differences in drug disposition.” Clinical Pharmacokinetics, vol. 45, no. 2, 2006, pp. 143-159.

- Bjornsson, Einar S. “Drug-induced liver injury ∞ an overview.” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 48, no. 9, 2013, pp. 997-1005.

- Handelsman, David J. “Testosterone ∞ From Basic Science to Clinical Applications.” Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Stanczyk, Frank Z. “Pharmacokinetics and potency of progestins used in hormonal replacement therapy.” Climacteric, vol. 10, no. S2, 2007, pp. 13-24.

Reflection

Having explored the intricate dance between sex steroids and hepatic enzymes, you now possess a deeper understanding of your body’s internal workings. This knowledge is not merely academic; it is a powerful lens through which to view your own health journey. Consider how these biological mechanisms might be influencing your daily experiences, from energy levels to mood stability. This understanding serves as a foundation, a starting point for a more informed conversation about your well-being.

The path to reclaiming vitality is often a personalized one, requiring a precise approach that respects your unique biological blueprint. This exploration of hepatic enzyme modulation by sex steroids highlights that true optimization extends beyond simple symptom management. It involves a commitment to understanding the underlying systems and working with your body’s innate intelligence. What insights have you gained about your own biological systems? How might this deeper knowledge guide your next steps toward a more vibrant, functional existence?