Fundamentals

Your body is a finely tuned biological system, a complex and interconnected network of communication pathways designed for one primary purpose ∞ to keep you functioning in a state of vitality. The feeling of energy, clarity, and resilience you experience when you are at your best is a direct reflection of this system operating with precision.

When that feeling begins to fade, replaced by fatigue, mental fog, or a general sense of decline, it is a signal that some part of this intricate communication has been disrupted. It is a deeply personal experience, a dissonance between how you feel and how you know you are capable of feeling. This journey to understand that disruption is the first step toward reclaiming your biological potential.

At the heart of this internal communication are molecules like hormones and peptides. Peptides are short chains of amino acids, the fundamental building blocks of proteins. They function as highly specific messengers, carrying precise instructions to cells and tissues. Think of them as keys, each crafted to fit a particular lock on a cell’s surface.

When a peptide key fits its lock, it initiates a specific biological response, such as signaling the release of a hormone, promoting tissue repair, or modulating inflammation. This specificity is their great power. It allows for targeted interventions that can help restore a particular function within the body’s vast communication network.

The Promise and the Peril of Precision

The capacity to use these biological keys offers a pathway to recalibrating systems that have gone awry. For instance, certain peptides can signal the pituitary gland to optimize its output, which can have cascading positive effects on metabolism, sleep, and recovery. This represents a sophisticated, targeted approach to wellness.

It moves beyond generalized solutions and toward personalized protocols that address the root of a specific biological imbalance. The goal is to support and restore the body’s own inherent mechanisms for health.

This precision, however, creates a profound ethical dilemma when these therapies enter a global marketplace marked by deep inequality. The core of the issue in developing nations is a collision between urgent human need and the absence of a robust regulatory framework to ensure safety and efficacy.

When people are suffering, they will seek solutions. In a well-regulated environment, the peptides available are verified for purity, dosage, and safety, administered under clinical guidance. In a developing nation with porous regulations, the landscape changes dramatically. The demand for these therapies creates a vacuum, one that is often filled by counterfeit or substandard products that pose significant risks.

The absence of regulation in developing nations transforms a quest for wellness into a gamble with personal safety and long-term health.

This situation gives rise to a critical question of biological justice. Does access to safe, effective tools for managing one’s own health depend on geography and economic status? The ethical implications are rooted in this disparity. The very therapies that hold promise for restoring function in one part of the world can become instruments of harm in another.

The conversation about peptide therapy regulation in developing nations is a conversation about the fundamental right to safe medical care and the systems required to protect that right.

Why Is Regulatory Oversight so Important?

Regulatory bodies like the FDA in the United States or the EMA in Europe provide a critical function. They establish and enforce standards for drug manufacturing, purity, and clinical testing. This oversight ensures that when a physician prescribes a therapy, the product contains the correct active ingredient at the correct dose, free from harmful contaminants like bacteria or heavy metals. This process is resource-intensive, requiring advanced scientific expertise, testing laboratories, and a legal framework for enforcement.

Many developing nations lack this extensive infrastructure. The result is a market where it is difficult to distinguish between a legitimate pharmaceutical-grade product and a counterfeit one made in an illicit lab. For the individual seeking to improve their health, this creates an environment of profound uncertainty and risk.

The desire to feel better is universal, but the safeguards that should be in place to protect that desire are not. Understanding this disparity is the starting point for appreciating the full scope of the ethical challenge.

Intermediate

To fully grasp the ethical dimensions of peptide therapy regulation, one must first understand the mechanics of these protocols and the stark contrast between their intended application and their reality in an unregulated environment. These are not blunt instruments; they are precision tools designed to interact with specific physiological pathways.

Their safety and efficacy are entirely dependent on product purity, accurate dosing, and a clear understanding of the individual’s underlying biology. When these conditions are absent, the potential for harm increases exponentially.

Exploring Specific Peptide Protocols

Peptide therapies are designed to support the body’s natural signaling processes. They often work by stimulating the body’s own production of hormones or other signaling molecules, rather than simply replacing them. This approach aims to restore the system’s natural rhythm and function. Let’s examine a few examples:

- Sermorelin / Ipamorelin CJC-1295 ∞ This is a combination of Growth Hormone Releasing Peptides (GHRPs). Sermorelin, Ipamorelin, and CJC-1295 are secretagogues, meaning they signal the pituitary gland to produce and release its own growth hormone (GH). This is done in a pulsatile manner that mimics the body’s natural rhythms. The intended clinical use is for adults with age-related GH decline, seeking to improve sleep quality, enhance recovery, reduce body fat, and support lean muscle mass. The protocol requires subcutaneous injections, typically administered at night to align with the body’s natural GH pulse.

- PT-141 (Bremelanotide) ∞ This peptide works differently. It acts on the central nervous system to directly influence sexual arousal. It is a melanocortin receptor agonist, and its mechanism is neurological. It is used to address sexual dysfunction, particularly low libido in women and erectile dysfunction in men that does not respond to traditional treatments. Its administration is via subcutaneous injection prior to sexual activity.

- Tesamorelin ∞ This is a growth hormone-releasing factor (GRF) analog. It is a more potent stimulator of growth hormone release and has been specifically studied and approved for the reduction of visceral adipose tissue (deep abdominal fat) in certain populations. Its use requires precise, medically supervised protocols.

The effectiveness of these protocols is predicated on the purity of the peptide chain and the accuracy of its dosage. A contaminated vial or an incorrectly dosed product can lead to severe consequences, including infection, allergic reactions, or unintended biological effects.

How Does Regulatory Absence Distort Patient Choice?

In a regulated healthcare system, a patient’s journey into peptide therapy involves several critical checkpoints. It begins with a consultation and comprehensive lab work to identify a genuine clinical need. This is followed by a prescription from a licensed physician, who sources the therapy from a compounding pharmacy that is subject to stringent quality controls. The patient receives education on proper administration and potential side effects. This entire process constitutes true informed consent.

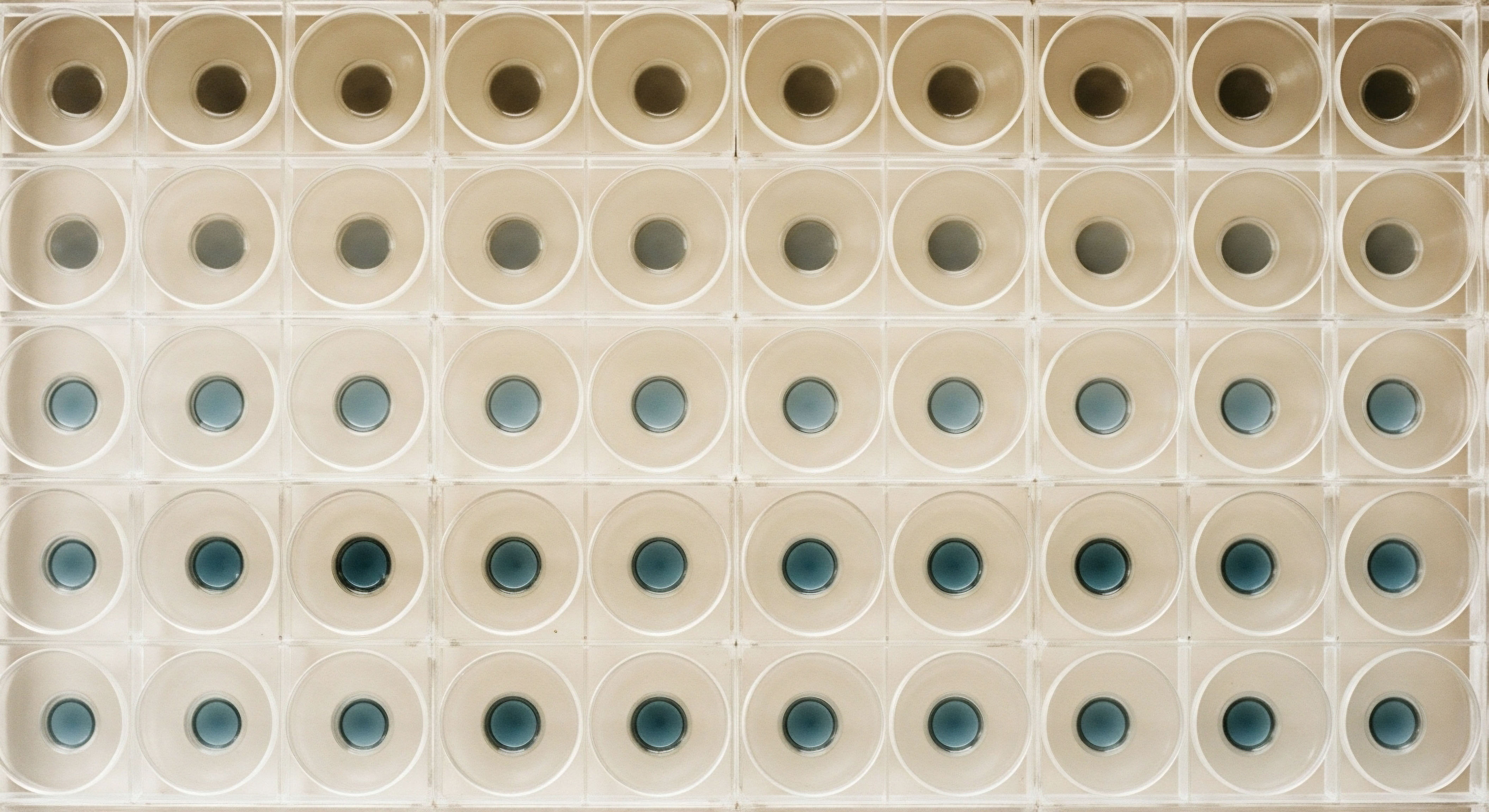

In a developing nation with weak or non-existent regulation, this entire structure collapses. The “choice” to use peptide therapy becomes distorted by a lack of reliable information and safe options. The following table illustrates the divergence between the ideal and the perilous reality.

In resource-limited settings, the concept of informed consent is compromised by a market flooded with products of unknown origin and quality.

| Aspect of Care | Regulated Environment (Ideal) | Unregulated Environment (Reality in Many Developing Nations) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Assessment |

Comprehensive blood work and physician consultation to establish clinical need and rule out contraindications. |

Self-diagnosis based on online forums or anecdotal advice. No clinical workup to assess suitability or risk. |

| Sourcing of Therapy |

Prescription-only access from a licensed compounding pharmacy adhering to purity and sterility standards. |

Purchase from unregulated online websites, black market dealers, or “research chemical” suppliers with no quality control. |

| Product Quality |

Guaranteed purity, concentration, and sterility, verified by third-party testing. |

Unknown. High risk of contamination (bacteria, heavy metals), incorrect substance, or sub-therapeutic/overly potent dosage. |

| Dosing and Administration |

Precise, individualized dosing protocol prescribed by a physician. Education on sterile injection techniques. |

Guesswork based on informal online protocols. High risk of improper dosing and non-sterile administration, leading to infection or adverse effects. |

| Monitoring and Follow-Up |

Regular follow-up with the physician to monitor efficacy, manage side effects, and adjust protocols based on follow-up lab work. |

No medical oversight. Individuals are left to manage side effects on their own, with no recourse or professional guidance. |

The Tangible Risks of an Unregulated Market

The ethical implications are not abstract; they manifest as real-world harm. The proliferation of counterfeit and substandard medical products is a recognized public health crisis in many developing countries. The World Health Organization has reported that a significant percentage of drugs sold in parts of Asia and Africa are fake or of poor quality. When this problem extends to injectable therapies like peptides, the risks are magnified.

These risks include:

- Infection ∞ Non-sterile manufacturing processes can introduce bacteria into vials. Using contaminated needles or improper injection techniques can lead to localized skin infections, abscesses, or life-threatening systemic infections like sepsis.

- Immune Response ∞ Poorly synthesized peptides can contain impurities or be fragmented. The body may recognize these as foreign invaders, triggering an adverse immune response. This can range from allergic reactions to the development of antibodies that attack the peptide, rendering it ineffective, or worse, cross-react with the body’s own proteins.

- Unpredictable Biological Effects ∞ A product sold as one peptide could be another entirely, or it could be a cocktail of unknown substances. The user might be injecting a substance with completely different and potentially dangerous effects on their endocrine system. This is a form of biological roulette.

- Toxic Contamination ∞ Unregulated labs may use solvents or other chemicals that are not fully purged from the final product. The long-term health consequences of injecting trace amounts of industrial chemicals or heavy metals are a serious concern.

This reality transforms the ethical landscape. It is a situation where the desire for self-improvement is exploited by a system that fails to provide basic protections. The burden of risk is shifted entirely onto the individual, who often lacks the resources to verify a product’s safety or to manage the consequences when something goes wrong.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the ethical quandaries surrounding peptide therapy in developing nations requires a systems-level perspective, integrating principles from bioethics, public health, and regulatory science. The issue transcends individual patient safety and extends to the concept of “bio-inequality” ∞ a state where a population’s health potential is systematically limited by weak institutional and regulatory structures.

The absence of a robust regulatory framework for novel therapeutics like peptides creates a permissive environment for exploitation, with profound and lasting biological and societal consequences.

What Are the Systemic Consequences of a Regulatory Vacuum?

The lack of effective regulation in developing countries is not a passive oversight; it is an active enabler of a dangerous parallel market. This market thrives on the economic and informational asymmetries between producers of counterfeit goods and vulnerable consumers. From a public health standpoint, this has several cascading negative effects.

First, it undermines trust in the entire healthcare system. When patients are harmed by counterfeit medicines, their confidence in medical professionals, pharmacies, and public health institutions erodes. This can lead to avoidance of the formal healthcare system altogether, even for essential treatments, creating a vicious cycle of poor health outcomes.

Second, it contributes to global health threats. A prime example is the development of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Injectable drugs prepared in non-sterile conditions can be contaminated with bacteria. If the drug itself is a substandard antibiotic, or if the user develops an infection that is then treated with a counterfeit antibiotic, it creates the perfect conditions for drug-resistant pathogens to emerge. These pathogens do not respect borders, posing a threat to global health security.

Third, it exposes populations to unethical research practices. Developing nations with weak regulatory oversight have historically been attractive locations for clinical trials sponsored by foreign entities. While ethical international research is possible and can be beneficial, the potential for exploitation is high.

This can include conducting trials without proper ethical review, issues with obtaining true informed consent from populations with low literacy or who are in a dependent relationship with researchers, and providing a standard of care during the trial that is lower than what would be acceptable in a high-income country.

The Ethical Trade-Off for Policymakers

Policymakers in developing nations face a difficult balancing act. The desire to attract foreign investment in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors is strong, as it can bring economic benefits and potentially increase access to new technologies. Implementing stringent regulations on par with those in the US or Europe can be perceived as a barrier to entry, potentially causing sponsors to conduct their research and business elsewhere. This creates a perceived trade-off between economic development and public health protection.

This trade-off is often a false dichotomy, however. The long-term economic costs of a poorly regulated medical market are immense. They include the direct costs of treating patients harmed by counterfeit drugs, the productivity losses from increased morbidity and mortality, and the damage to the reputation of the country’s export and healthcare sectors. The following table outlines the key challenges and consequences related to clinical trial and drug regulation in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

| Regulatory Challenge | Mechanism of Failure | Long-Term Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Local Review Capacity |

Clinical trials may proceed without adequate review by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board that understands the local context. |

Increased risk of exploitation of research participants and trials that are not scientifically or ethically sound. |

| Inadequate Enforcement |

Laws against counterfeit medicines may exist, but a lack of resources for inspection, testing, and prosecution means they are not enforced. |

A thriving black market that directly harms public health and erodes trust in the legitimate medical system. |

| Economic Pressures |

Governments may hesitate to impose strict regulations for fear of driving away pharmaceutical investment and research. |

A “race to the bottom” where regulatory standards are weakened, prioritizing short-term economic gain over long-term public health security. |

| Post-Trial Access |

A new, effective therapy is tested on a local population, but upon approval, it is priced out of reach for the very people who participated in the research. |

Populations bear the risks of research without reaping the benefits, a clear ethical breach of justice and beneficence. |

The presence of counterfeit peptides should be viewed as a symptom of this larger systemic failure. These products represent the most visible edge of a market that preys on the convergence of medical need, information disparity, and regulatory absence. Addressing the ethical implications requires moving beyond a focus on the individual user and toward strengthening the entire public health and regulatory apparatus.

A nation’s regulatory capacity for advanced therapeutics is a direct measure of its commitment to biological justice for its citizens.

Ultimately, the solution involves international cooperation, technology transfer to build local regulatory capacity, and a commitment from high-income nations and pharmaceutical companies to uphold the same ethical standards for safety and efficacy regardless of where a product is sold or a trial is conducted.

The biological well-being of an individual in a developing nation is of no less value than that of an individual in a developed one, and the systems designed to protect that well-being must reflect this fundamental principle.

References

- “Challenges of clinical trials in low- and middle-income countries.” International Psychiatry, vol. 9, no. 2, 2012, pp. 30-32.

- Rius-Ottenheim, N. et al. “Regulating international clinical research ∞ an ethical framework for policy-makers.” Journal of Medical Ethics, vol. 46, no. 5, 2020, pp. 324-331.

- Kelesidis, Theodoros, and Matthew E. Falagas. “Counterfeit or substandard antimicrobial drugs ∞ a review of the scientific evidence.” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, vol. 60, no. 2, 2007, pp. 214-236.

- Cockburn, R. et al. “The global threat of counterfeit drugs ∞ why industry and governments must act.” The Lancet, vol. 366, no. 9498, 2005, pp. 1673-1675.

- Borgonha, Sudhir. “Ethical Considerations of Conducting Clinical Research in Developing Countries.” The Journal of Clinical Research, vol. 2, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1-9.

- “Counterfeit/Fake and Substandard Medicines ∞ A Global Bioethical Issue Requiring A Global Approach.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, vol. 18, 2021, pp. 351-361.

- “Ethical and Regulatory Considerations in Peptide Drug Development.” Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 16, no. 5, 2024, pp. 7-8.

- De Cock, K. M. et al. “Shadow on the continent ∞ public health and HIV/AIDS in Africa in the 21st century.” The Lancet, vol. 360, no. 9326, 2002, pp. 67-72.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a framework for understanding the complex interplay between advanced wellness protocols and the global systems that govern them. Your own health journey is a deeply personal one, a dynamic process of listening to your body and seeking ways to restore its intended function. The knowledge of how these therapies work, and the critical importance of the structures that ensure their safety, is now part of your toolkit. This awareness is a form of empowerment.

Consider the immense trust we place in our medical systems. We trust that the vial in the physician’s hand contains exactly what it claims, in precisely the right concentration, free from any harm. This trust is the invisible bedrock of modern medicine. Reflect on what it means for this trust to be fragile or absent. How does it change the equation of personal health?

Your path forward is about making informed, conscious choices. It involves asking critical questions, seeking out qualified guidance, and understanding that a true protocol for wellness is a partnership. It is a collaboration between your own knowledge of your body and the expertise of a clinical guide who operates within a system of safety and accountability.

The pursuit of vitality is a worthy one. May your journey be guided by both scientific clarity and a deep appreciation for the systems that protect it.