Fundamentals

You stand at a unique crossroads in human history, a point where the ability to guide our own biology is becoming a tangible reality. The feelings of fatigue, the slow recovery from injury, the sense that your body is no longer keeping pace with your spirit ∞ these are profound personal experiences.

It is entirely natural to seek solutions that promise to restore your vitality and function. The world of tissue regeneration peptides emerges from this very human desire for wellness. These are molecules that speak the body’s native language, offering the potential to direct healing and renewal from within. Understanding their promise is the first step. Comprehending the deep ethical considerations of their long-term use is a journey of wisdom we will embark on together.

This exploration is a personal one, centered on empowering you with knowledge. We will move through the science of these powerful molecules, not as a detached observer, but as someone who is seeking to understand their own biological systems. The goal is to translate complex clinical science into a clear, usable framework.

This framework will allow you to evaluate the potential of these therapies while respecting the profound questions they raise about the nature of health, longevity, and human identity. We begin by building a solid foundation, ensuring you feel seen in your concerns and aspirations as we unpack the science together.

What Are Peptides and How Do They Work?

At its core, your body is a vast and intricate communication network. Hormones, neurotransmitters, and other signaling molecules are the messengers, carrying instructions that govern everything from your energy levels to your immune response. Peptides are a specific class of these messengers. They are small chains of amino acids, the fundamental building blocks of proteins.

Think of them as short, precise sentences in the body’s chemical language. While a large protein might be a full chapter of instructions, a peptide is a single, clear command ∞ “begin repair,” “reduce inflammation,” “release growth hormone.”

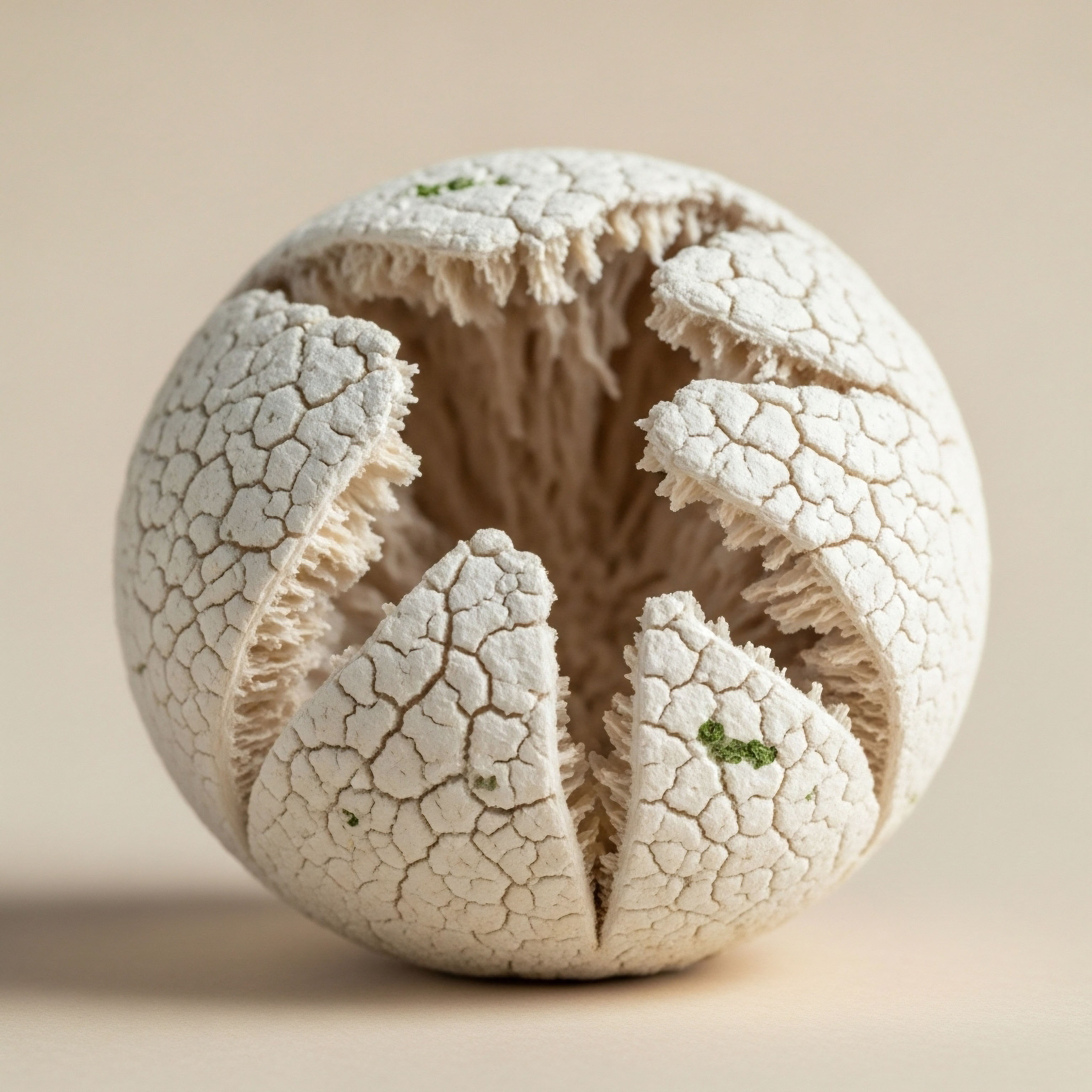

Tissue regeneration peptides are specific sequences that have been identified for their roles in healing and restoration. For instance, some peptides can signal to your cells to produce more collagen, the protein that provides structure to your skin and connective tissues.

Others can attract immune cells to a site of injury to clean up damage and lay the groundwork for new tissue. They work by binding to specific receptors on the surface of your cells, much like a key fitting into a lock.

Once the peptide key turns the lock, it initiates a cascade of events inside the cell, leading to a desired biological outcome. This specificity is what makes them so powerful. They can target particular processes in the body with a high degree of precision.

Peptides are the body’s own signaling molecules, short amino acid chains that issue specific commands to cells to initiate processes like healing and growth.

The appeal of using these peptides therapeutically is clear. By reintroducing or supplementing these signaling molecules, the intention is to amplify the body’s own regenerative capacities. If an injury is slow to heal, perhaps the local concentration of healing peptides is insufficient.

If age has slowed collagen production, introducing a peptide that stimulates it could, in theory, restore a more youthful cellular function. This approach feels intuitive because it works with the body’s existing systems. It is a form of biological guidance, a way of reminding the body of its innate capacity for self-repair.

The Initial Ethical Questions on the Horizon

As we consider the prospect of using these powerful molecules over extended periods, a new set of questions comes into view. These are not just questions of medical safety; they are inquiries into the very nature of what it means to be well and to age.

The journey into long-term peptide use is a journey into uncharted territory, and it is our responsibility to proceed with awareness and foresight. The ethical considerations begin the moment we move from addressing a specific, short-term injury to contemplating a continuous intervention in our baseline biology.

The first and most immediate consideration is that of long-term safety. Many of these peptides have been studied in laboratory settings and in short-term animal or human trials. The results often show promise in accelerating healing or improving certain biomarkers.

What remains largely unknown, however, are the consequences of sustained use over months, years, or even decades. The body’s signaling systems are exquisitely balanced. Continuously sending a powerful “grow” or “repair” signal could have unforeseen consequences. Could it disrupt the delicate feedback loops that govern our endocrine system? Could it, in some contexts, promote unwanted cellular growth? These are not questions with easy answers, and the absence of long-term data creates an ethical imperative for caution and transparency.

Informed Consent in an Evolving Landscape

A central pillar of medical ethics is the principle of informed consent. This means that an individual must be given a clear and complete picture of the potential risks and benefits of a treatment before deciding to proceed. In the context of long-term peptide use, providing truly comprehensive information is a profound challenge.

How can a clinician fully inform a patient about the risks of a therapy when those risks themselves are not fully understood? This is a critical ethical dilemma. The conversation must shift from a simple recitation of known side effects to an open acknowledgment of the existing uncertainties. It requires a partnership between the individual and the provider, one built on mutual respect for the knowns and the unknowns.

The responsibility falls on both sides. The provider has an ethical duty to be radically transparent about the limits of current knowledge. The individual has a responsibility to themselves to ask deep questions, to seek understanding, and to be comfortable with the level of uncertainty they are accepting. This is particularly true in a field where many substances are sourced through channels outside of traditional regulatory oversight, where purity, dosage, and contamination are additional variables of risk.

Defining the Line between Therapy and Enhancement

Another significant ethical consideration is the distinction between using peptides for therapy versus using them for enhancement. Where do we draw the line? Is using a peptide to heal a torn ligament a form of therapy? Most would agree that it is. Is using that same peptide to build muscle mass beyond one’s genetic potential also therapy?

Or is it enhancement? What about using peptides to slow the visible signs of aging? Is aging a disease to be treated or a natural process to be accepted?

These are not merely philosophical questions. They have real-world implications for regulation, access, and societal values. If these peptides are defined purely as therapeutic agents for specific diseases, their availability will be limited and controlled. If they are seen as tools for human enhancement, a completely different set of social and ethical questions arises.

This distinction is rarely clear-cut. A person seeking to recover from a chronic, nagging injury that limits their quality of life may see their use of peptides as purely therapeutic. An outside observer might see it as an attempt to gain a competitive edge or reverse the natural course of aging. The lived experience of the individual is a critical component of this ethical calculus.

Intermediate

Having established a foundational understanding of tissue regeneration peptides and the initial ethical questions they present, we can now proceed to a more detailed examination of their clinical application and the nuanced dilemmas that arise. This stage of our journey requires a closer look at specific protocols, the biological mechanisms they influence, and the complex risk-benefit analysis that every individual must undertake.

Here, the “Clinical Translator” voice becomes even more vital, as we connect the molecular science to the lived experience of seeking proactive wellness.

The decision to engage with long-term peptide protocols is a significant one. It involves a commitment to a regimen that directly interfaces with your body’s most fundamental signaling pathways. As we explore these protocols, we will maintain a dual focus ∞ understanding the intended biological effects and simultaneously examining the ethical responsibilities that accompany such powerful interventions. The goal is to build a sophisticated awareness that moves beyond simple pros and cons, allowing for a truly informed personal health philosophy.

A Deeper Look at Specific Tissue Regeneration Peptides

The world of regenerative peptides is vast, with dozens of molecules being explored for various purposes. To ground our discussion, we will focus on two of the most well-known peptides in the context of tissue repair ∞ BPC-157 and TB-500. Understanding their proposed mechanisms of action allows us to appreciate their therapeutic potential while also identifying the specific ethical questions tied to their use.

BPC-157 Body Protective Compound

BPC-157 is a synthetic peptide chain composed of 15 amino acids, derived from a protein found in human gastric juice. It has garnered significant attention for its potential systemic healing capabilities. Preclinical studies, mostly in animal models, suggest that BPC-157 can accelerate the healing of a wide variety of tissues, including muscle, tendon, ligament, bone, and skin.

It appears to work through several pathways, most notably by promoting angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels. An adequate blood supply is critical for delivering oxygen and nutrients to a site of injury, and BPC-157 seems to be a potent stimulator of this process. It also appears to have a modulating effect on growth factors and to possess anti-inflammatory properties.

The ethical considerations with BPC-157 are directly tied to its power and the current state of research. Because it is believed to have systemic effects, its long-term use raises questions about its impact on tissues beyond the intended target.

If it promotes blood vessel growth to heal a tendon, could it also promote blood vessel growth in other areas where it might be undesirable? The research on its long-term safety in humans is sparse.

While many users in online forums and communities report positive outcomes with few side effects, this anecdotal evidence is not a substitute for rigorous, controlled, long-term clinical trials. An individual choosing to use BPC-157 is operating in a space of significant scientific uncertainty, which places a heavy burden on the principle of informed consent.

TB-500 Thymosin Beta-4

TB-500 is a synthetic version of Thymosin Beta-4, a naturally occurring protein found in virtually all human and animal cells. Thymosin Beta-4 is a key regulator of actin, a protein that is a fundamental component of the cell’s cytoskeleton and is essential for cell migration, division, and differentiation.

By promoting actin polymerization, TB-500 is thought to facilitate the migration of cells to sites of injury, a critical step in the healing process. It also has potent anti-inflammatory effects and can promote the growth of new blood vessels, similar to BPC-157.

The ethical questions surrounding TB-500 mirror those of BPC-157 but with an added layer of complexity due to its fundamental role in cellular mechanics. Intervening in a process as basic as actin regulation could have widespread and unforeseen consequences over the long term.

While its natural counterpart, Thymosin Beta-4, is ubiquitous in the body, the administration of a synthetic version at therapeutic doses represents a significant departure from normal physiology. The table below outlines some of the key distinctions and overlapping considerations for these two peptides, highlighting the nuanced ethical landscape.

| Feature | BPC-157 | TB-500 (Synthetic Thymosin Beta-4) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Proposed Mechanism | Promotes angiogenesis (new blood vessel growth) and modulates growth factors. | Upregulates actin production, promoting cell migration and differentiation. |

| Source | Synthetic peptide derived from a human gastric protein. | Synthetic version of a naturally occurring protein found in all cells. |

| Primary Ethical Concern | Potential for unwanted systemic angiogenic effects with long-term use. Lack of human trial data. | Interference with a fundamental cellular process (actin regulation) could have widespread, unpredictable long-term effects. |

| Regulatory Status | Generally sold as a “research chemical,” not approved for human consumption by major regulatory bodies. | Similar to BPC-157, it is not approved for human therapeutic use and exists in a regulatory gray area. |

| Informed Consent Challenge | Communicating the unknown risks of long-term, systemic growth signaling. | Explaining the potential consequences of altering a core component of cellular structure and function over time. |

The Ethics of Access and Equity

Beyond the questions of individual safety and consent lies a broader set of societal ethical considerations. As these powerful regenerative technologies become more refined and sought after, we must confront the issue of access. Who gets to benefit from these therapies? At present, most peptide therapies are not covered by insurance and can be expensive.

This creates a two-tiered system where those with the financial means can access cutting-edge wellness protocols, while others cannot. This raises profound questions about justice and fairness in health.

The unequal distribution of advanced regenerative therapies threatens to create a new form of biological stratification based on wealth.

This economic barrier is compounded by a knowledge barrier. Navigating the world of peptide therapy requires a significant degree of self-education and access to specialized clinicians who often operate outside of the mainstream medical system. This can create a situation where those who are already privileged in terms of education and resources are better equipped to take advantage of these new technologies.

As a society, we have an ethical obligation to consider how these powerful tools can be deployed in a way that reduces, rather than exacerbates, existing health disparities.

The Role of “Bio-Hacking” and Self-Experimentation

Much of the current use of regenerative peptides occurs within the “bio-hacking” community, a culture that champions self-experimentation and the democratization of health information. This movement has been instrumental in bringing attention to these therapies and fostering a community of shared knowledge. However, it also raises its own set of ethical concerns.

- Purity and Safety ∞ When individuals source peptides from unregulated online suppliers, they face risks related to product purity, correct dosage, and potential contamination. The ethical imperative for safety is shifted from a regulated system to the individual consumer, who may lack the tools to verify what they are injecting into their body.

- Absence of Medical Oversight ∞ Self-experimentation without the guidance of a qualified clinician can be dangerous. A medical professional can help interpret blood work, monitor for side effects, and adjust protocols based on an individual’s unique physiology. Bypassing this oversight increases the risk of adverse outcomes.

- Reporting Bias ∞ The anecdotal evidence generated by these communities can be valuable, but it is also subject to significant bias. Success stories are often amplified, while negative experiences or lack of results may be underreported. This can create a skewed perception of a peptide’s efficacy and safety profile.

The ethical challenge here is to find a balance. We must respect individual autonomy and the right of people to make decisions about their own bodies. At the same time, we must promote a culture of safety and responsibility. This could involve developing better systems for third-party product testing, creating educational resources that provide a balanced view of the evidence, and fostering a more open dialogue between the mainstream medical community and these pioneering user communities.

Academic

Our exploration now transitions to a level of academic and scientific depth appropriate for the complexity of the subject. Having covered the foundational concepts and intermediate clinical dilemmas, we will now analyze the ethical considerations of long-term peptide use through the rigorous lens of systems biology, focusing specifically on the potential for neuroendocrine disruption.

This perspective moves beyond localized tissue effects to consider the organism as a whole, an interconnected network of systems where a single intervention can have far-reaching and unanticipated consequences. This is the frontier of personalized medicine, and it carries a commensurate level of ethical responsibility.

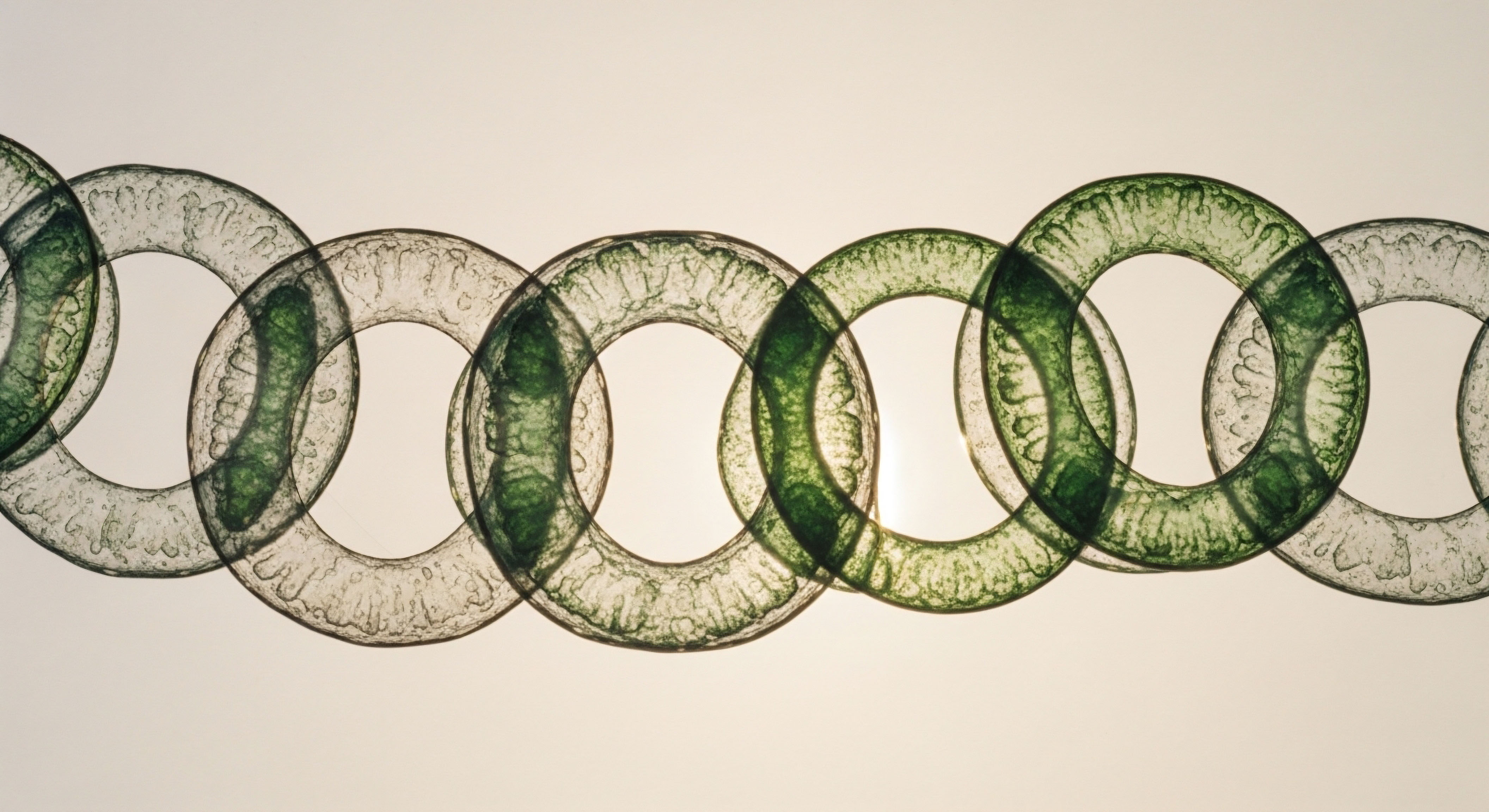

The core of our academic inquiry rests on a critical question ∞ What are the systemic consequences of chronically activating powerful signaling pathways designed for acute, localized repair? To answer this, we must delve into the intricate communication that occurs between the body’s repair mechanisms and its master regulatory systems, particularly the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.

These axes are the central command centers of the endocrine system, governing stress response, metabolism, reproduction, and overall homeostasis. The chronic introduction of exogenous peptides represents a novel input into this exquisitely balanced system, the long-term ramifications of which are largely uncharacterized.

Neuroendocrine Axis Disruption a Central Ethical Concern

The ethical imperative to “first, do no harm” requires a profound understanding of the potential for iatrogenic effects. In the context of long-term peptide use, one of the most significant yet under-discussed risks is the potential for dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system.

Many regenerative peptides, including BPC-157 and TB-500, have demonstrated interactions with inflammatory pathways and growth factor signaling. These very pathways are in constant cross-talk with the HPA and HPG axes. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines can stimulate the HPA axis, leading to cortisol release. Growth factors can influence the release of pituitary hormones. Introducing a powerful, persistent signal into this network raises several critical concerns.

Feedback Loop Attenuation and Receptor Downregulation

A fundamental principle of endocrinology is the concept of the negative feedback loop. For example, the HPG axis operates on a feedback system where testosterone, produced by the gonads, signals back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to decrease the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thus maintaining hormonal balance. Chronic stimulation from an external source can disrupt this delicate mechanism.

Consider a hypothetical scenario where a regenerative peptide, through its anti-inflammatory or growth-promoting effects, indirectly influences the signaling environment of the hypothalamus. If this peptide chronically dampens an inflammatory signal that the hypothalamus uses as a cue, it could alter the baseline secretion of releasing hormones like GnRH or CRH.

Over time, the body may adapt to this new, artificial baseline. This could lead to a downregulation of receptors in the pituitary or target glands, meaning they become less sensitive to the body’s natural signaling molecules. The consequence could be a state of induced secondary hypogonadism or adrenal insufficiency that only becomes apparent after the peptide is discontinued, leaving the individual’s natural systems unable to function optimally.

The ethical problem is that this is a subtle, slow-developing form of harm. It would not appear as an acute side effect. It would manifest as a gradual decline in endogenous function, a dependency on the exogenous peptide to maintain a state of perceived wellness. This creates a difficult situation for informed consent, as the very nature of the potential harm is a slow erosion of the body’s own homeostatic resilience.

What Is the True Meaning of Long-Term Efficacy?

The evaluation of long-term peptide use demands a more sophisticated definition of efficacy. The current paradigm often focuses on short-term symptomatic relief or improvement in specific biomarkers. A user might report that their joint pain has disappeared or that their recovery from exercise is faster.

From a systems biology perspective, this is an incomplete picture. True efficacy must be measured not just by the presence of a desired effect, but by the absence of negative adaptations in the broader system.

A more rigorous, ethical framework for assessing efficacy would include the following parameters:

- Homeostatic Resilience ∞ Does the therapy enhance the body’s ability to return to a healthy baseline after a stressor, or does it create a dependency that weakens this resilience? This could be measured by assessing HPA axis function through cortisol awakening response tests or by evaluating HPG axis integrity after a course of therapy.

- Metabolic Flexibility ∞ Does long-term use improve or impair the body’s ability to switch efficiently between fuel sources (glucose and fatty acids)? Chronic activation of growth pathways could, in theory, push cellular metabolism in a direction that ultimately reduces this flexibility.

- Immunological Competence ∞ While many peptides have anti-inflammatory effects, what is the long-term consequence of chronically suppressing certain inflammatory pathways? Inflammation is a critical part of the immune response and tissue remodeling. Does long-term suppression lead to an impaired ability to fight off certain pathogens or to properly resolve future injuries?

This level of analysis is currently absent from the public discourse and even from most clinical practices in this area. The ethical challenge for the medical and scientific communities is to develop and advocate for these more comprehensive models of assessment. Without them, we risk optimizing for short-term gains at the expense of long-term systemic health.

| Potential Long-Term Systemic Risk | Affected Biological System | Mechanism of Action | Ethical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Hypogonadism | Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) Axis | Chronic signaling alters GnRH pulsatility, leading to downregulation of LH/FSH receptors in the pituitary and gonads. | Creates potential for dependency and iatrogenic infertility or hormonal deficiency. Challenges the definition of “restorative” therapy. |

| HPA Axis Dysregulation | Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis | Persistent anti-inflammatory signals may alter the baseline cortisol rhythm, leading to adrenal fatigue or hyper-reactivity. | Risk of creating long-term mood disorders, metabolic syndrome, and impaired stress resilience. |

| Oncogenic Potential | Cell Cycle Regulation | Chronic stimulation of growth factors (e.g. angiogenesis) could potentially accelerate the growth of nascent, undiagnosed tumors. | The most severe potential harm, requiring extreme caution and contraindication in individuals with a history or high risk of cancer. |

| Immunological Imbalance | Innate and Adaptive Immune System | Sustained suppression of specific inflammatory cytokines may impair the body’s ability to mount an effective response to pathogens. | The pursuit of anti-aging or regeneration could paradoxically increase vulnerability to acute illness. |

The Unregulated Experiment and the Call for Responsible Research

We are currently in the midst of a large, uncontrolled, post-market experiment in long-term peptide use. This experiment is being conducted by thousands of individuals worldwide, largely outside the purview of traditional research institutions. From a purely ethical standpoint, this situation is fraught with peril. It lacks the fundamental safeguards of clinical research ∞ institutional review board (IRB) oversight, standardized protocols, data collection, and long-term follow-up.

Without structured, long-term research, we are navigating the future of regenerative medicine by anecdote and assumption, a precarious approach for technologies that interact with our core biology.

The academic and medical communities have an ethical obligation to engage with this reality. This does not mean simply condemning the practice of self-experimentation. It means creating pathways for responsible research. This could take the form of establishing patient registries to collect long-term observational data from current users.

It could involve designing and funding rigorous, independent clinical trials to investigate the long-term systemic effects of the most commonly used peptides. It requires a collaborative effort between researchers, clinicians, and the user communities themselves to move from a state of collective uncertainty to one of shared knowledge.

The pursuit of human vitality is a powerful force. Our ethical duty is to ensure that this pursuit is guided by wisdom, foresight, and a deep respect for the intricate biological systems that define our existence.

References

- Finn, Ryder. “Ethical and Regulatory Considerations in Peptide Drug Development.” Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 16, no. 5, 2024, pp. 7-8.

- Munsie, M. & Hyun, I. “A systematic review of the ethical implications of tissue engineering for regenerative purposes.” Bioethics, vol. 36, no. 5, 2022, pp. 526-539.

- Pickart, L. & Margolina, A. “Regenerative and Protective Actions of the GHK-Cu Peptide in the Light of the New Gene Data.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 19, no. 7, 2018, p. 1987.

- Rehman, K. et al. “Role of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Health and Disease.” Journal of Steroids and Hormonal Science, vol. 7, no. 1, 2016, p. 168.

- Khavinson, V. K. “Peptides, Genome, and Aging.” Gerontology, vol. 48, no. 2, 2002, pp. 88-92.

- De Boer, J. & van der Meer, A. D. “Grand challenges in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.” Frontiers in Medical Technology, vol. 4, 2022, p. 1045230.

- Schillaci, M. A. “The limits of human enhancement.” The American Journal of Bioethics, vol. 9, no. 3, 2009, pp. 58-60.

- Sehgal, A. & Mignot, E. “Genetics of sleep and sleep disorders.” Cell, vol. 146, no. 2, 2011, pp. 194-207.

- Anisimov, V. N. Khavinson, V. K. & Morozov, V. G. “Twenty years of study on effects of pineal peptide preparation epithalamin in experimental gerontology and oncology.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 719, no. 1, 1994, pp. 483-493.

- Kipshidze, N. et al. “Therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with limb ischemia.” Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018, pp. 451-456.

Reflection

You have journeyed through the complex world of tissue regeneration peptides, from the foundational science to the deepest ethical inquiries. The knowledge you now possess is a powerful tool. It allows you to look at the promise of regenerative medicine with both hope and a discerning eye.

This understanding is the starting point of a deeply personal process of inquiry. The path forward is not about finding a single right answer, but about asking the right questions for your own life, your own values, and your own unique biology. Consider how this information resonates with your personal health goals.

What does it mean for you to be well? How do you define vitality? The ultimate purpose of this knowledge is to empower you to become a more informed, active, and conscious participant in your own health journey, equipped to make choices that align with your deepest sense of well-being.

Glossary

tissue regeneration peptides

ethical considerations

signaling molecules

tissue regeneration

long-term peptide use

long-term safety

informed consent

human enhancement

regenerative peptides

bpc-157

growth factors

blood vessel growth

naturally occurring protein found

tb-500

actin regulation could have widespread

peptide therapy

bio-hacking

neuroendocrine disruption

systems biology

hpa axis

hpg axis