Fundamentals

Many individuals experience subtle shifts in their physical and emotional well-being, often dismissed as simply “getting older” or “stress.” Perhaps you have noticed changes in your energy levels, sleep patterns, mood stability, or even how your body retains weight. These experiences can feel isolating, leaving one to wonder if these changes are an inevitable part of life.

Yet, these sensations are frequently signals from a finely tuned internal communication network ∞ your endocrine system. Understanding these internal messages, particularly those related to estrogen, offers a pathway to reclaiming vitality and function.

Estrogen, often considered a primary female sex hormone, plays a far broader role than commonly perceived. It influences bone density, cardiovascular health, cognitive function, and even the integrity of skin and hair. This biochemical messenger circulates throughout the body, interacting with various tissues and systems.

When its levels become imbalanced, either too high or too low, or when its metabolic pathways are disrupted, the body sends signals that manifest as the symptoms many individuals experience. These signals are not random; they are expressions of a system seeking equilibrium.

The Body’s Internal Messaging System

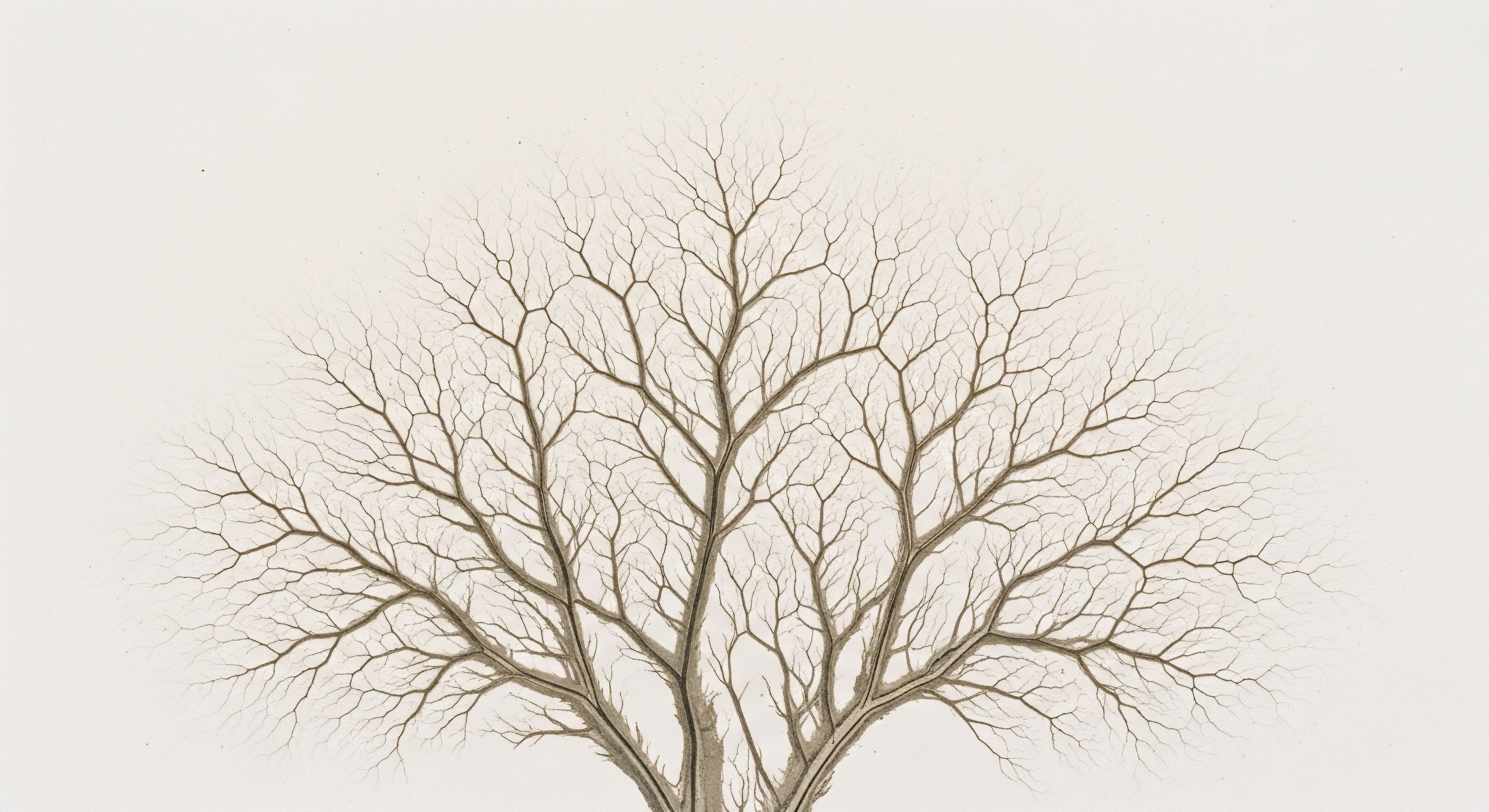

Consider your body as a vast, interconnected communication network. Hormones, including estrogen, act as messengers, carrying instructions from one part of the system to another. These messages dictate a multitude of physiological processes, from cellular growth to energy regulation. When the messages are clear and balanced, the system operates with optimal efficiency. When the messages are distorted or excessive, the system can become overwhelmed, leading to a cascade of effects that impact overall well-being.

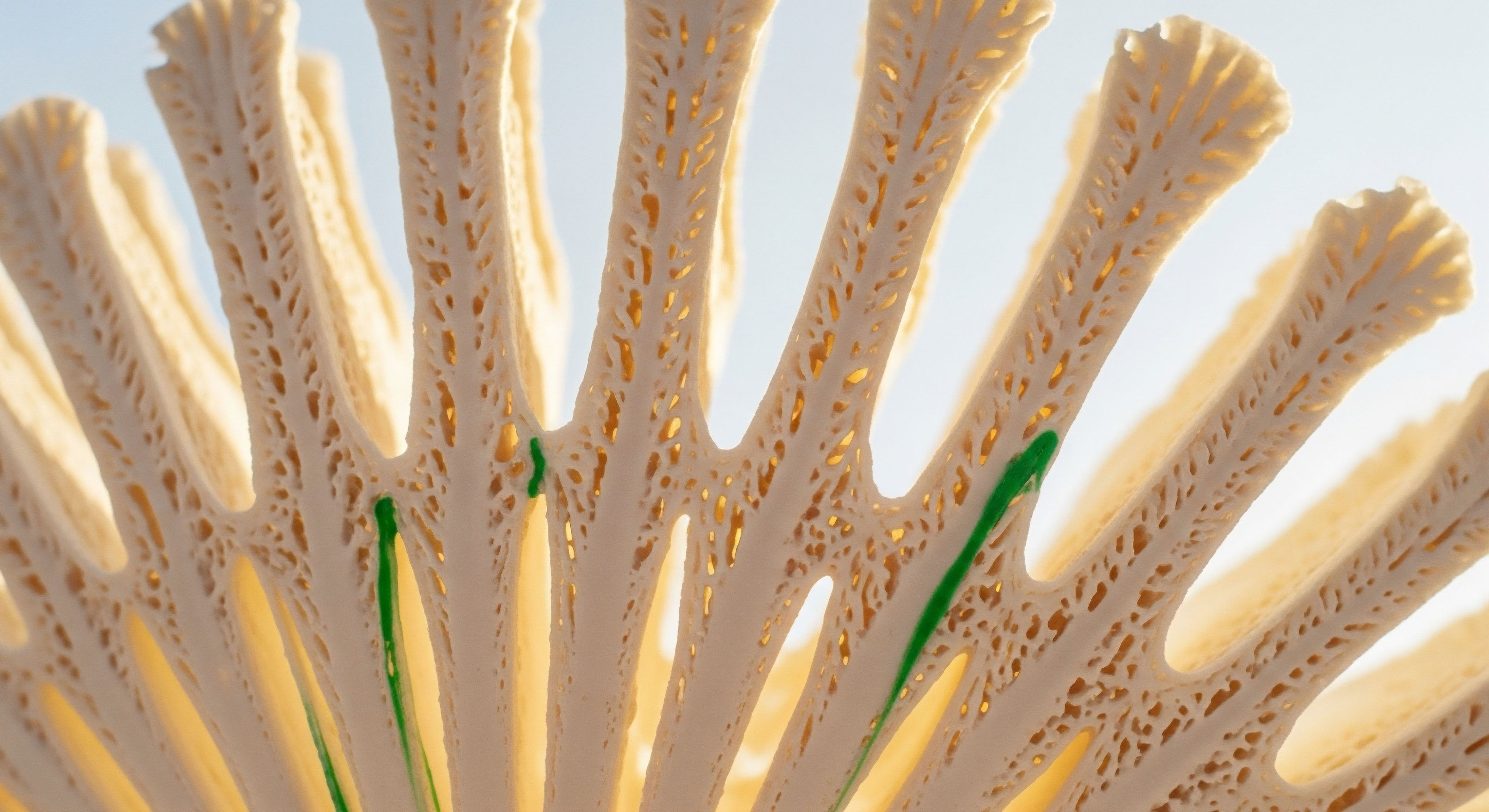

The production and regulation of estrogen involve a complex interplay of glands and organs, primarily the ovaries in pre-menopausal women, and adrenal glands and fat tissue in post-menopausal women and men. The brain, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, orchestrates this production through a feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. This axis functions like a sophisticated thermostat, constantly monitoring hormone levels and adjusting production to maintain balance.

Estrogen’s influence extends beyond reproductive health, affecting bone density, heart function, and cognitive clarity.

Estrogen’s Journey through the Body

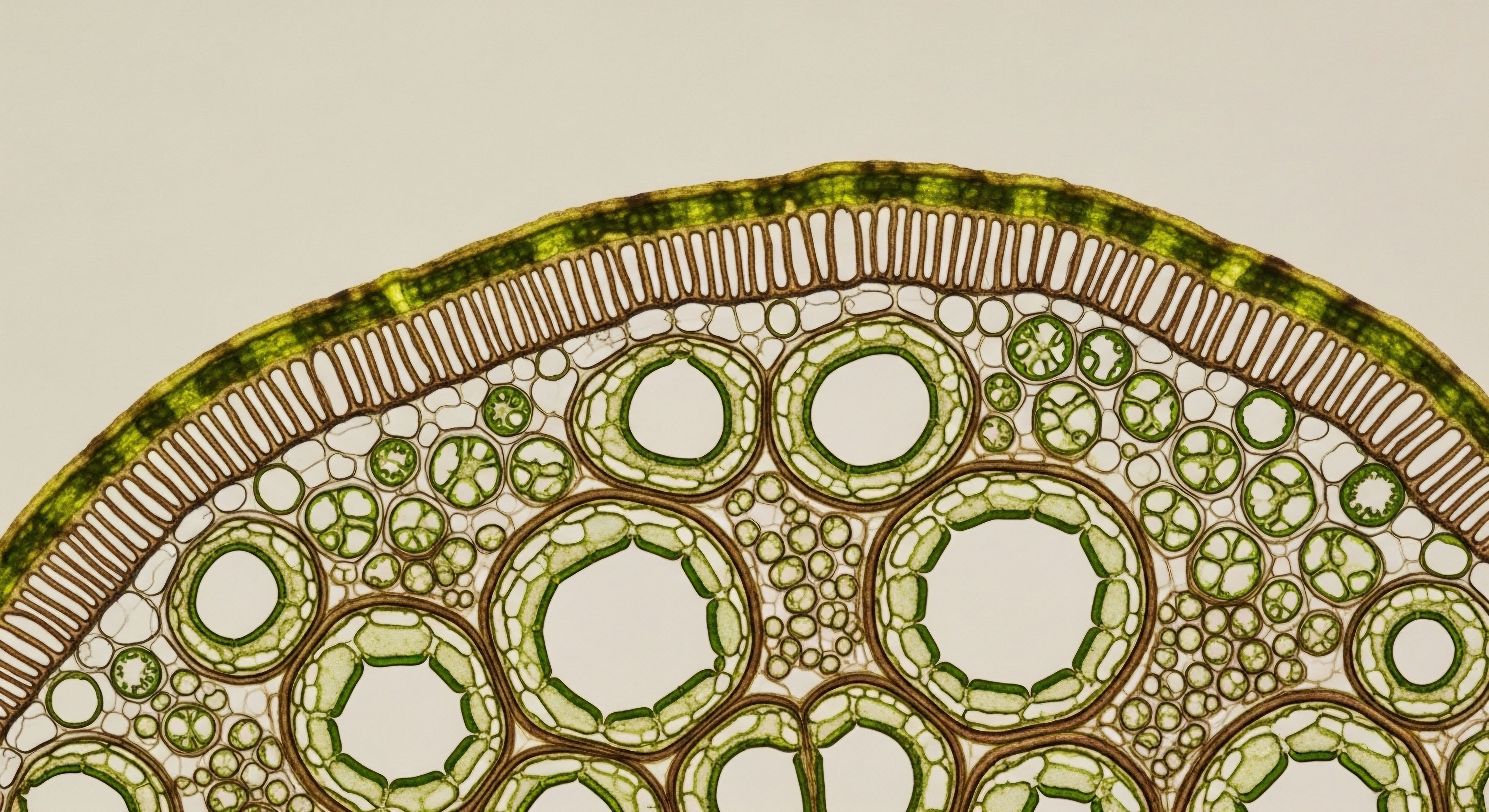

Once produced, estrogen circulates and performs its functions. However, it does not remain in the body indefinitely. It must be processed and eliminated to prevent accumulation and maintain balance. This process, known as estrogen metabolism, primarily occurs in the liver. The liver transforms active forms of estrogen into various metabolites, some of which are less potent, and others that can be more or less favorable depending on their structure.

The liver’s detoxification pathways are critical for this process. These pathways involve two main phases. In Phase I detoxification, enzymes, particularly those from the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family, modify estrogen molecules. This initial step can produce different types of estrogen metabolites. For instance, estradiol can be converted into 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1) or 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1). The ratio of these metabolites holds significant implications for health, with a higher ratio of 2-OHE1 to 16α-OHE1 generally considered more protective.

Following Phase I, Phase II detoxification involves conjugation, where the modified estrogen metabolites are attached to other molecules, such as glucuronic acid or sulfate. This conjugation makes them water-soluble, allowing for their excretion from the body via bile and urine. A healthy liver and efficient detoxification pathways are therefore fundamental to proper estrogen modulation.

The Gut Microbiome’s Role in Estrogen Balance

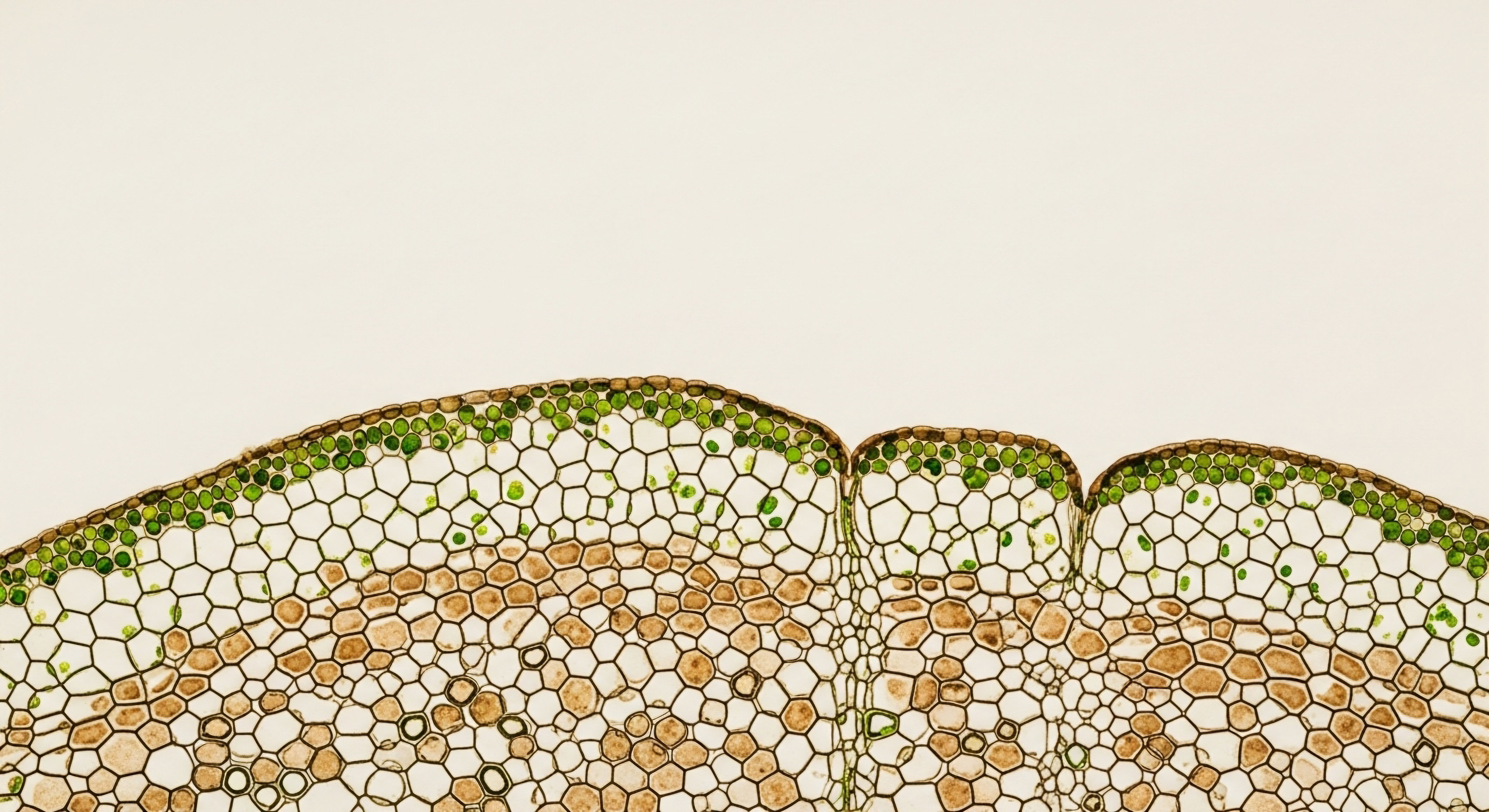

Beyond the liver, the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the gut microbiome, plays a surprisingly significant role in estrogen metabolism. Certain bacteria in the gut produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme can de-conjugate estrogen metabolites that have been processed by the liver and sent to the intestines for excretion.

When de-conjugated, these estrogens can be reabsorbed into the bloodstream, increasing the body’s overall estrogen load. This reabsorption can contribute to conditions associated with estrogen dominance, where estrogen levels are relatively high compared to other hormones.

A balanced and diverse gut microbiome supports healthy estrogen elimination. Conversely, an imbalanced gut, often referred to as dysbiosis, can lead to increased beta-glucuronidase activity, potentially hindering the body’s ability to excrete estrogens effectively. This highlights the interconnectedness of digestive health and hormonal equilibrium, demonstrating that dietary choices impact not only nutrient absorption but also the delicate balance of our internal biochemistry.

Intermediate

With a foundational understanding of estrogen’s journey and its metabolic pathways, we can now consider how specific dietary adjustments can influence this delicate balance. Dietary choices are not merely about caloric intake; they are powerful signals that instruct our biological systems, including how estrogen is produced, metabolized, and eliminated. Tailoring your nutritional intake can serve as a potent strategy for supporting optimal hormonal health.

Targeting Estrogen Metabolism through Diet

Dietary adjustments for estrogen modulation primarily aim to support the liver’s detoxification processes, promote healthy gut function, and influence the production of estrogen metabolites. This involves focusing on specific food groups and macronutrient ratios that have been shown to impact these pathways.

Cruciferous Vegetables and Indole Compounds

One of the most well-researched dietary interventions involves the consumption of cruciferous vegetables. This family includes broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, and kale. These vegetables contain unique compounds called glucosinolates, which are converted into active compounds like indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and its more stable derivative, diindolylmethane (DIM), when the vegetables are chopped or chewed.

I3C and DIM are particularly noteworthy for their influence on Phase I liver detoxification. They promote the activity of CYP enzymes, specifically shifting estrogen metabolism towards the production of the beneficial 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1) metabolite, rather than the potentially more proliferative 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1). A higher 2-OHE1 to 16α-OHE1 ratio is associated with a more favorable estrogen profile and may reduce certain health risks.

Incorporating a generous daily intake of these vegetables, perhaps 1-2 cups, can provide the precursors for these beneficial compounds. Steaming or lightly cooking them helps preserve their nutrient content while making them easier to digest.

The Role of Dietary Fiber

Dietary fiber, abundant in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts, plays a significant role in estrogen modulation, primarily through its impact on gut health. Fiber helps bind to excess estrogen and its metabolites in the intestines, facilitating their excretion from the body. This binding action prevents the reabsorption of estrogens that have been processed by the liver and sent to the digestive tract.

A diet rich in fiber also supports a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. A balanced microbiome can help regulate beta-glucuronidase activity, reducing the likelihood of estrogen de-conjugation and subsequent reabsorption. Aiming for 25-35 grams of fiber daily from varied plant sources can significantly support healthy estrogen elimination.

Dietary fiber aids in the elimination of excess estrogen by binding to it in the intestines, preventing reabsorption.

Lignans and Phytoestrogens

Certain plant compounds, known as phytoestrogens, can also influence estrogen activity in the body. Lignans, a type of phytoestrogen found in flax seeds, sesame seeds, and some grains, are particularly relevant. Once consumed, gut bacteria convert lignans into active compounds like enterolactone and enterodiol. These compounds possess a weaker estrogenic effect than endogenous human estrogen. They can bind to estrogen receptors, potentially blocking stronger, naturally occurring estrogens from binding, thereby exerting a modulating effect.

This competitive binding can be beneficial in situations of estrogen excess, as the weaker phytoestrogens occupy receptor sites without stimulating the same potent cellular responses. Including a tablespoon or two of ground flax seeds daily can be a simple way to incorporate lignans into your dietary pattern.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Inflammation

Chronic inflammation can disrupt hormonal balance, including estrogen metabolism. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), flax seeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, possess potent anti-inflammatory properties. By reducing systemic inflammation, omega-3s can indirectly support healthier estrogen pathways and overall endocrine function.

They contribute to cellular membrane fluidity and signaling, which are fundamental to proper hormone receptor function. Regular consumption of omega-3 rich foods or a high-quality supplement can be a valuable component of a diet aimed at estrogen modulation.

Dietary Patterns for Hormonal Balance

Beyond individual nutrients, adopting a holistic dietary pattern can profoundly influence estrogen levels.

How Does a Mediterranean-Style Dietary Pattern Influence Estrogen Balance?

The Mediterranean diet, characterized by its emphasis on whole, unprocessed foods, healthy fats, lean proteins, and abundant plant-based foods, aligns well with the principles of estrogen modulation. This dietary pattern naturally incorporates many of the beneficial components discussed ∞ high fiber from fruits, vegetables, and legumes; healthy fats from olive oil and nuts; and anti-inflammatory compounds. Studies suggest that a varied dietary pattern, similar to the Mediterranean diet, can support healthier estrogen levels.

Conversely, a “Western dietary pattern,” often high in red meats, processed foods, and refined carbohydrates, has been associated with higher estradiol levels. This underscores the importance of shifting away from inflammatory, nutrient-poor foods.

What Role Does Weight Management Play in Estrogen Modulation?

Body weight, particularly excess adipose tissue, significantly impacts estrogen levels. Fat cells, or adipocytes, contain the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens (male hormones) into estrogens. Higher body fat percentage can lead to increased aromatase activity, resulting in elevated estrogen levels, especially in postmenopausal women and men.

Weight loss, achieved through a combination of dietary adjustments and regular physical activity, can significantly reduce circulating estrogen levels and improve the balance of estrogen metabolites. This reduction in estrogen load can alleviate symptoms associated with estrogen dominance and contribute to overall metabolic health.

How Does Alcohol Consumption Affect Estrogen Metabolism?

Alcohol consumption can directly interfere with the liver’s ability to metabolize and excrete estrogen. The liver prioritizes the detoxification of alcohol, which can slow down its capacity to process hormones. This can lead to a buildup of estrogen in the body. Reducing or eliminating alcohol intake is a straightforward yet powerful dietary adjustment for supporting healthy estrogen modulation.

Here is a summary of key dietary adjustments and their mechanisms:

| Dietary Component | Key Foods | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Broccoli, Cauliflower, Brussels Sprouts, Cabbage, Kale | Provide I3C/DIM, shifting estrogen metabolism to beneficial 2-OHE1. |

| Dietary Fiber | Fruits, Vegetables, Whole Grains, Legumes, Nuts | Binds to excess estrogen in intestines, promotes excretion, supports gut microbiome. |

| Lignans (Phytoestrogens) | Flax Seeds, Sesame Seeds | Weakly bind to estrogen receptors, modulating stronger endogenous estrogen effects. |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Fatty Fish, Flax Seeds, Chia Seeds, Walnuts | Reduces systemic inflammation, supports cellular function. |

| Lean Proteins | Poultry, Fish, Legumes, Tofu | Supports liver detoxification enzymes, aids in satiety and weight management. |

| Antioxidant-Rich Foods | Berries, Dark Leafy Greens, Colorful Vegetables | Protects cells from oxidative stress, supports overall metabolic health. |

Academic

A deeper examination of dietary adjustments for estrogen modulation requires an understanding of the intricate biochemical pathways and systemic interconnections that govern hormonal equilibrium. This perspective moves beyond simple dietary recommendations to reveal the sophisticated dialogue between nutrition, genetics, and environmental factors in shaping an individual’s estrogenic landscape.

The Liver’s Central Role in Estrogen Biotransformation

The liver stands as the primary organ responsible for estrogen biotransformation, a multi-step process designed to render steroid hormones water-soluble for excretion. This process is highly dependent on specific enzyme systems and nutrient cofactors.

Phase I Hydroxylation Pathways

In Phase I, the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily of enzymes catalyzes the hydroxylation of estrogens. The primary estrogens, estradiol (E2) and estrone (E1), can be hydroxylated at different positions on their steroid ring, leading to distinct metabolites. The most significant hydroxylation pathways occur at the C-2, C-4, and C-16 positions.

- 2-Hydroxylation ∞ Catalyzed primarily by CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, this pathway produces 2-hydroxyestrone (2-OHE1) and 2-hydroxyestradiol (2-OHE2). These “catechol estrogens” are considered less estrogenic and are often referred to as “good” estrogens due to their reduced proliferative activity. They are rapidly methylated by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), further reducing their activity and preparing them for excretion.

- 16α-Hydroxylation ∞ Catalyzed by CYP3A4 and CYP2C19, this pathway yields 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1). This metabolite possesses strong estrogenic activity and can bind covalently to DNA, potentially contributing to cellular proliferation and certain health risks.

- 4-Hydroxylation ∞ Catalyzed by CYP1B1, this pathway produces 4-hydroxyestrone (4-OHE1). While less abundant than 2-OHE1 or 16α-OHE1, 4-OHE1 is also a catechol estrogen and can be associated with oxidative DNA damage if not properly methylated.

The balance between these hydroxylation pathways is profoundly influenced by dietary components. For instance, as previously noted, compounds like DIM from cruciferous vegetables upregulate CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, thereby favoring the 2-hydroxylation pathway and increasing the beneficial 2-OHE1 to 16α-OHE1 ratio.

Phase II Conjugation and Elimination

Following hydroxylation, Phase II enzymes conjugate these metabolites, making them more water-soluble for excretion. Key Phase II pathways include:

- Glucuronidation ∞ Catalyzed by UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), this is a major pathway for estrogen conjugation. Glucuronidated estrogens are excreted via bile into the intestines or via urine.

- Sulfation ∞ Catalyzed by sulfotransferases (SULTs), this pathway also produces water-soluble estrogen sulfates for urinary excretion.

- Methylation ∞ As mentioned, COMT methylates catechol estrogens (2-OHE1, 4-OHE1), reducing their reactivity and facilitating their excretion. This process requires methyl donors, such as folate, vitamin B12, and betaine, and the amino acid methionine.

Nutritional deficiencies in these cofactors can impair Phase II detoxification, leading to a backlog of estrogen metabolites and potential reabsorption. For example, a diet lacking in B vitamins can compromise methylation, leaving more reactive catechol estrogens in circulation.

The Estrobolome and Gut-Liver Axis

The concept of the estrobolome refers to the collection of gut bacteria capable of metabolizing estrogens. These bacteria produce the enzyme beta-glucuronidase, which de-conjugates glucuronidated estrogens in the gut lumen. This de-conjugation liberates active estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into the enterohepatic circulation, thereby increasing the body’s systemic estrogen load.

An imbalanced gut microbiome, characterized by an overgrowth of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria, can lead to elevated circulating estrogen levels. Dietary factors that influence the gut microbiome, such as fiber intake and the consumption of fermented foods, directly impact the estrobolome’s activity. A diet rich in diverse plant fibers promotes a healthy gut environment, supporting beneficial bacteria that help maintain appropriate beta-glucuronidase activity and facilitate estrogen excretion.

The gut microbiome, through the estrobolome, directly influences estrogen reabsorption, highlighting the digestive system’s role in hormonal balance.

Adipose Tissue and Aromatase Activity

Adipose tissue, or body fat, is not merely a storage depot for energy; it is an active endocrine organ. It contains the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens (like testosterone and androstenedione) into estrogens (estradiol and estrone). This conversion is a significant source of estrogen, particularly in postmenopausal women and men.

Increased adiposity, especially visceral fat, correlates with higher aromatase activity and consequently, elevated estrogen levels. This mechanism explains why weight management is a cornerstone of estrogen modulation strategies. Dietary interventions that promote healthy weight loss, such as calorie-controlled, nutrient-dense diets, directly reduce the substrate for aromatase activity and the overall estrogen burden.

Here is a detailed look at the interplay of systems in estrogen modulation:

| System/Pathway | Key Enzymes/Components | Dietary Influences | Impact on Estrogen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Phase I Detoxification | CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP1B1, CYP3A4 | Cruciferous vegetables (DIM, I3C), antioxidants, B vitamins | Shifts hydroxylation towards beneficial 2-OHE1, reduces reactive metabolites. |

| Liver Phase II Detoxification | UGTs, SULTs, COMT | Folate, B12, Betaine, Methionine, Sulfur-rich foods | Conjugates metabolites for excretion, supports methylation of catechol estrogens. |

| Gut Microbiome (Estrobolome) | Beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria | Dietary fiber, prebiotics, probiotics, fermented foods | Regulates de-conjugation and reabsorption of estrogens; influences excretion. |

| Adipose Tissue | Aromatase enzyme | Caloric intake, macronutrient balance, weight management | Converts androgens to estrogens; higher fat mass increases estrogen production. |

| Inflammation Pathways | Cytokines, Prostaglandins | Omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, anti-inflammatory foods | Reduces systemic inflammation that can disrupt hormonal signaling. |

Beyond Estrogen ∞ Interconnectedness with Metabolic Health

The discussion of estrogen modulation through diet cannot exist in isolation from broader metabolic health. Insulin resistance, a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin, is closely linked to hormonal imbalances, including estrogen dysregulation. High insulin levels can increase androgen production in women, which in turn can be converted to estrogen via aromatase in adipose tissue.

A diet that stabilizes blood sugar, rich in complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, and healthy fats, supports insulin sensitivity. This approach indirectly contributes to healthier estrogen balance by mitigating the metabolic drivers of hormonal disruption. The emphasis on whole, unprocessed foods, as seen in a Mediterranean-style pattern, naturally supports both optimal estrogen metabolism and robust metabolic function.

Understanding these deep biological mechanisms allows for a more precise and personalized approach to dietary adjustments. It is not merely about avoiding certain foods, but about strategically nourishing the body to optimize its inherent capacity for hormonal self-regulation and overall vitality.

References

- Lord, Richard S. Bongiovanni, Bradley, & Bralley, J. Alexander. “Estrogen metabolism and the diet-cancer connection ∞ Rationale for assessing the ratio of urinary hydroxylated estrogen metabolites.” Altern Med Rev 2002;7(2):112-129.

- Amare, Dagnachew Eyachew. “Anti-Cancer and Other Biological Effects of a Dietary Compound 3,3ʹ-Diindolylmethane Supplementation ∞ A Systematic Review of Human Clinical Trials.” Dove Medical Press, 2020;12:1483-1499.

- Sepkovic, D. W. et al. “Brassica Vegetable Consumption Shifts Estrogen Metabolism in Healthy Postmenopausal Women.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2009;18(3):793-799.

- Thompson, H. J. et al. “The Effects of Diet and Exercise on Endogenous Estrogens and Subsequent Breast Cancer Risk in Postmenopausal Women.” Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 Sep 20;12:732255.

Reflection

Having explored the intricate relationship between dietary choices and estrogen modulation, a significant realization emerges ∞ your body possesses an extraordinary capacity for self-regulation. The information presented here is not a rigid prescription, but rather a guide to understanding the profound influence of what you consume on your internal biochemical landscape. Each dietary adjustment discussed serves as a tool, offering a means to support your body’s innate intelligence in maintaining hormonal equilibrium.

This knowledge marks a starting point, an invitation to consider your personal journey with renewed insight. Your unique biological system responds to inputs in its own way, and truly personalized wellness protocols often require careful observation and professional guidance. As you move forward, consider how these insights might inform your daily choices, allowing you to proactively support your vitality and function, not as a compromise, but as a deliberate act of self-care.