Fundamentals

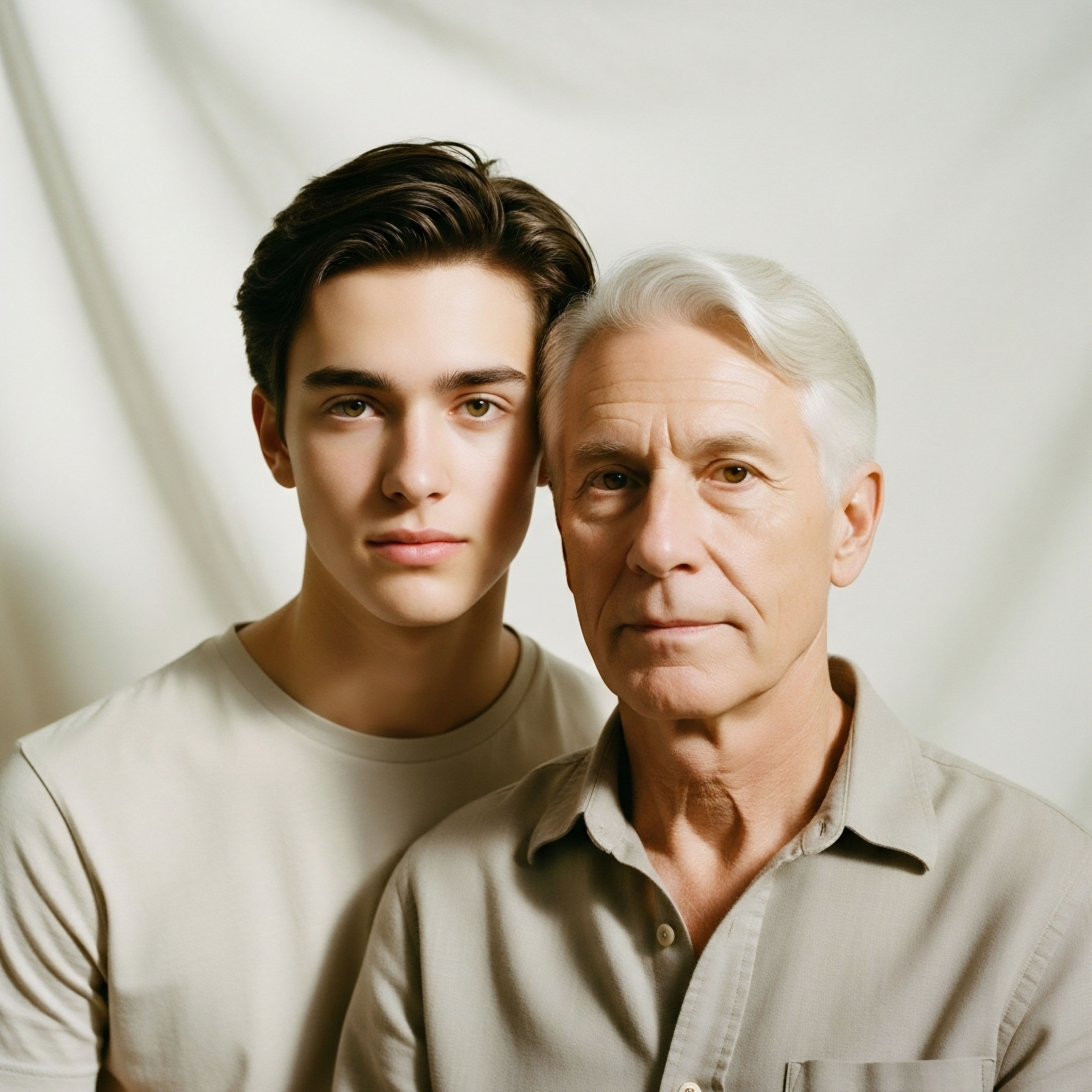

Many individuals experience a subtle yet persistent shift in their daily experience, a gradual erosion of the vitality that once felt inherent. Perhaps you notice a lingering fatigue that no amount of rest seems to resolve, or a diminishing drive that affects both personal pursuits and professional endeavors.

There might be a quiet frustration with changes in body composition, where maintaining muscle mass becomes increasingly difficult and unwanted fat accumulates with ease. These are not merely signs of getting older; they represent a call from your biological systems, signaling a potential imbalance within the intricate network of your endocrine function. Understanding these shifts, recognizing them as more than just a passing phase, marks the first step toward reclaiming your full potential.

The human body operates as a sophisticated orchestra, with hormones serving as the conductors, directing a myriad of physiological processes. Among these vital chemical messengers, testosterone holds a central position, particularly for men. It is commonly associated with male characteristics, yet its influence extends far beyond muscle mass and libido.

This steroid hormone plays a critical role in maintaining bone density, regulating red blood cell production, influencing mood stability, and supporting cognitive function. When its levels decline, the effects ripple across multiple bodily systems, manifesting as a collection of symptoms that can significantly diminish one’s quality of life.

What Is the Role of Testosterone in Male Physiology?

Testosterone, primarily produced in the testes, is a potent androgen. Its synthesis begins with cholesterol, undergoing a series of enzymatic conversions to become the active hormone. This biochemical pathway is tightly regulated by a complex feedback loop involving the brain’s hypothalamus and pituitary gland.

The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which then prompts the pituitary to secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH directly stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone, while FSH supports sperm production within the seminiferous tubules. This intricate communication system, known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, ensures that testosterone levels remain within a healthy physiological range.

The impact of testosterone extends to virtually every cell type in the male body. It binds to androgen receptors, initiating gene expression changes that drive protein synthesis, support metabolic rate, and influence neurological pathways. A decline in this hormone can therefore affect energy metabolism, leading to reduced insulin sensitivity and an increased propensity for fat storage.

It can also alter neurotransmitter balance, contributing to mood disturbances such as irritability or a lack of motivation. The subjective experience of feeling “off” or “not quite myself” often correlates directly with these underlying biochemical shifts.

Testosterone acts as a fundamental conductor within the male physiological orchestra, influencing energy, mood, and physical composition.

Recognizing the Signals of Hormonal Imbalance

Identifying low testosterone begins not with a laboratory test, but with an honest assessment of one’s lived experience. Many men report a constellation of symptoms that, when viewed individually, might seem unrelated or easily dismissed as typical aging. These include a persistent lack of energy, a noticeable decrease in physical strength and endurance, and a reduced interest in sexual activity.

Beyond these common indicators, some individuals describe a decline in mental sharpness, difficulty concentrating, or a general sense of apathy. Sleep patterns can also be disrupted, leading to insomnia or non-restorative sleep, further exacerbating feelings of fatigue.

Physical changes often accompany these subjective feelings. A reduction in muscle mass, even with consistent exercise, and an increase in abdominal fat are frequently observed. Bone density may also diminish over time, increasing the risk of fractures. Hair thinning, particularly body hair, can also be a subtle sign.

These physical manifestations are direct consequences of testosterone’s widespread influence on tissue maintenance and metabolic regulation. Recognizing these collective signals is paramount, as they serve as the initial prompts for a deeper clinical investigation.

Why Do Symptoms Vary among Individuals?

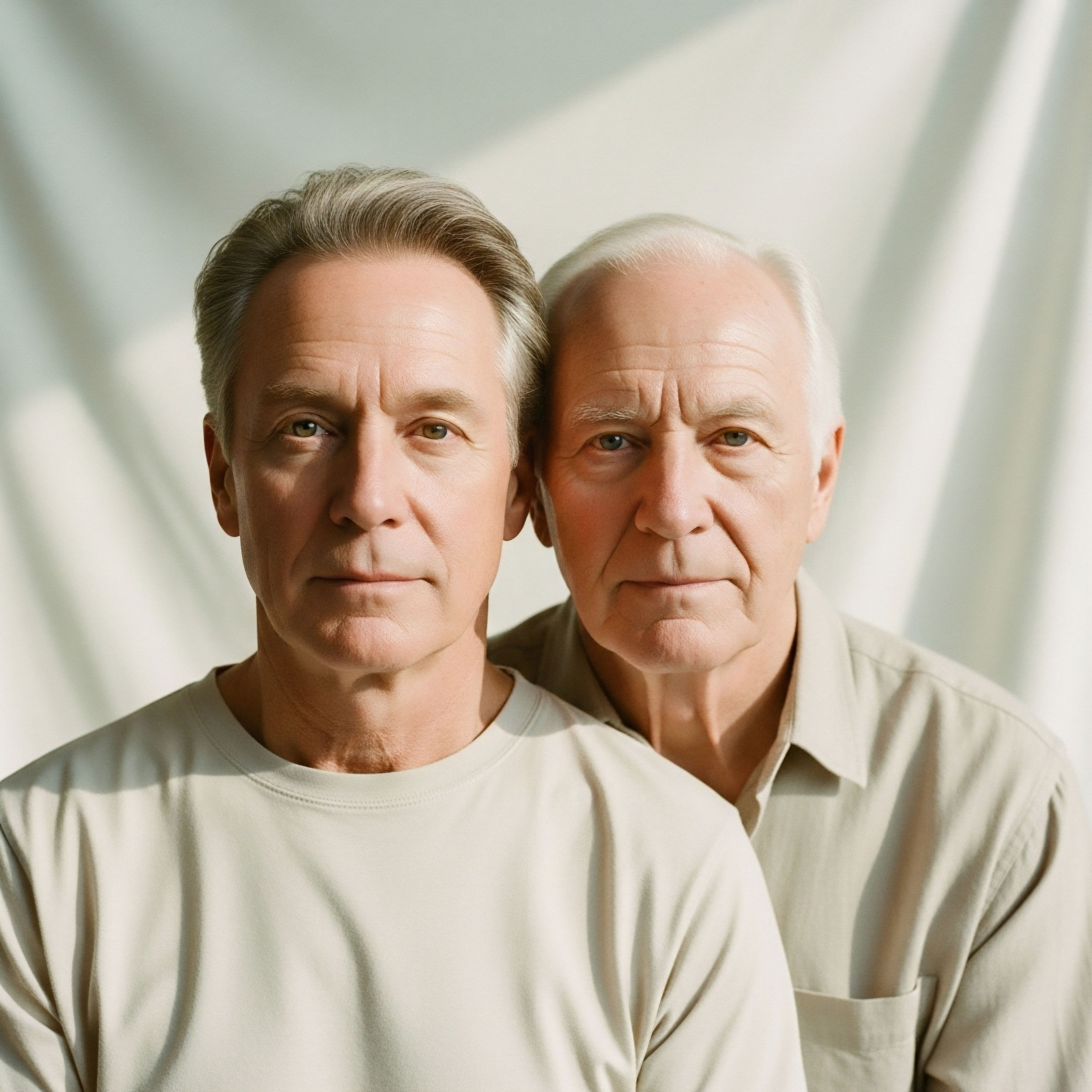

The presentation of low testosterone symptoms is highly individual, influenced by genetic predispositions, lifestyle factors, and the presence of co-existing health conditions. Some men may experience pronounced sexual dysfunction, while others primarily struggle with mood changes or chronic fatigue.

This variability underscores the importance of a personalized assessment rather than relying on a single symptom as a definitive indicator. The body’s compensatory mechanisms can also mask or delay the onset of overt symptoms, making the decline insidious. For instance, an individual with a highly active lifestyle might initially compensate for lower testosterone levels through rigorous training, only to find that their recovery suffers or their performance plateaus despite continued effort.

Environmental factors, such as chronic stress, poor sleep hygiene, and inadequate nutrition, can also contribute to the symptomatic burden and potentially depress testosterone production. The adrenal glands, for example, produce cortisol in response to stress, and chronically elevated cortisol can negatively impact the HPG axis, indirectly suppressing testosterone synthesis. This interconnectedness means that addressing hormonal balance often requires a holistic view of an individual’s overall health and lifestyle, rather than focusing solely on a single hormone level.

Intermediate

Once the subjective experience aligns with the potential for low testosterone, the next step involves a precise clinical evaluation. This moves beyond simply acknowledging symptoms to quantifying the biochemical reality within the body. Establishing a diagnosis of low testosterone, or hypogonadism, requires a careful interpretation of specific laboratory markers, coupled with a thorough clinical assessment. It is not solely about a single number but about understanding the context of that number within an individual’s overall health profile and symptom presentation.

What Are the Key Laboratory Markers for Low Testosterone?

The cornerstone of diagnosing low testosterone involves blood tests, specifically measuring circulating testosterone levels. However, a single measurement is rarely sufficient due to the diurnal variation of the hormone, with levels typically highest in the morning. Therefore, multiple morning blood draws are often recommended to establish a reliable baseline.

The most important measurements include ∞

- Total Testosterone ∞ This measures the total amount of testosterone in the blood, including both bound and unbound forms. Reference ranges can vary between laboratories, but generally, levels below 300 ng/dL (nanograms per deciliter) are considered indicative of low testosterone in symptomatic men. However, symptoms can appear at higher levels for some individuals.

- Free Testosterone ∞ This measures the biologically active form of testosterone, which is not bound to proteins and is therefore available to tissues. Free testosterone provides a more accurate reflection of the hormone’s availability at the cellular level. Levels below 6.5 ng/dL are often considered low.

- Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) ∞ This protein binds to testosterone, making it unavailable for tissue action. Elevated SHBG levels can lead to lower free testosterone, even if total testosterone appears normal. Understanding SHBG levels is critical for a complete picture of androgen status.

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) ∞ These pituitary hormones provide insight into the cause of low testosterone. Elevated LH and FSH in the presence of low testosterone suggest primary hypogonadism (a problem with the testes), while low or normal LH and FSH suggest secondary hypogonadism (a problem with the pituitary or hypothalamus).

- Prolactin ∞ Elevated prolactin levels can suppress GnRH secretion, leading to secondary hypogonadism.

- Estradiol (E2) ∞ Testosterone can convert to estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. Monitoring estradiol is important, especially during testosterone optimization protocols, as excessively high estrogen can lead to side effects.

Accurate diagnosis of low testosterone relies on a comprehensive panel of morning blood tests, not just a single total testosterone reading.

A comprehensive diagnostic approach considers not only the absolute values of these markers but also their ratios and how they interact within the endocrine system. For instance, a man with a total testosterone of 350 ng/dL might still experience significant symptoms if his SHBG is high, resulting in very low free testosterone.

Conversely, a man with a slightly lower total testosterone but low SHBG might have adequate free testosterone and be asymptomatic. This highlights the need for a nuanced interpretation by a clinician experienced in hormonal health.

Understanding Diagnostic Thresholds and Clinical Context

While specific numerical thresholds exist for laboratory values, the diagnosis of low testosterone is ultimately a clinical one, meaning it integrates both laboratory data and the patient’s symptom profile. The Endocrine Society, for example, defines hypogonadism as a clinical syndrome that includes both consistent symptoms and unequivocally low serum testosterone concentrations. This dual requirement ensures that treatment is initiated for genuine deficiency, not merely a low number in an asymptomatic individual.

Consider the following table outlining typical diagnostic considerations ∞

| Diagnostic Criterion | Description and Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|

| Persistent Symptoms | Fatigue, low libido, erectile dysfunction, mood changes, decreased muscle mass, increased body fat, poor sleep. These must be consistent and not attributable to other conditions. |

| Morning Total Testosterone | Two separate measurements below 300 ng/dL (or laboratory-specific lower limit). Samples collected between 7:00 AM and 10:00 AM are preferred due to diurnal variation. |

| Morning Free Testosterone | Measurements below 6.5 ng/dL, especially relevant when SHBG is elevated or total testosterone is borderline. |

| LH and FSH Levels | Used to differentiate between primary (testicular failure, high LH/FSH) and secondary (pituitary/hypothalamic dysfunction, low/normal LH/FSH) hypogonadism, guiding treatment strategy. |

| Exclusion of Other Causes | Ruling out other medical conditions (e.g. thyroid dysfunction, sleep apnea, chronic illness, medication side effects) that can mimic or contribute to low testosterone symptoms. |

The process of diagnosis also involves a thorough medical history, including medication review, assessment of chronic conditions, and lifestyle factors. Certain medications, such as opioids or glucocorticoids, can suppress testosterone production. Chronic illnesses like diabetes, obesity, and kidney disease are also associated with lower testosterone levels. A comprehensive evaluation ensures that the root cause of the symptoms is accurately identified, leading to the most appropriate and effective intervention.

Navigating Treatment Protocols for Testosterone Optimization

For men diagnosed with symptomatic low testosterone, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is a primary intervention. The goal of TRT is to restore physiological testosterone levels, alleviating symptoms and improving overall well-being. A common protocol involves weekly intramuscular injections of Testosterone Cypionate, typically at a concentration of 200mg/ml. This method provides a steady release of the hormone, avoiding the peaks and troughs associated with less frequent dosing.

However, TRT is not a standalone treatment; it is part of a comprehensive hormonal optimization protocol. To maintain natural testosterone production and fertility, especially in younger men or those desiring future fertility, Gonadorelin is often included. This peptide, administered via subcutaneous injections twice weekly, stimulates the pituitary to release LH and FSH, thereby supporting testicular function.

Another crucial component is managing estrogen levels. Testosterone can convert to estrogen in the body through the aromatase enzyme. While some estrogen is necessary for male health, excessive levels can lead to side effects such as gynecomastia (breast tissue development), water retention, and mood swings. To mitigate this, an aromatase inhibitor like Anastrozole is often prescribed, typically as an oral tablet twice weekly. This medication helps to block the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, maintaining a healthy balance.

In some cases, particularly for men seeking to restore their own production or avoid exogenous testosterone, medications like Enclomiphene may be considered. Enclomiphene selectively blocks estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary, thereby increasing LH and FSH secretion and stimulating endogenous testosterone production. This approach can be particularly useful for men with secondary hypogonadism who wish to preserve fertility. The choice of protocol is highly individualized, based on the specific diagnostic findings, patient goals, and clinical presentation.

Academic

The diagnostic journey for low testosterone extends into the intricate mechanisms of the endocrine system, demanding a deep understanding of neuroendocrine feedback loops and cellular signaling pathways. Moving beyond basic definitions, a truly comprehensive assessment considers the interplay of various hormonal axes and their impact on systemic physiology. This academic exploration reveals that testosterone deficiency is rarely an isolated event but often a manifestation of broader metabolic or neuroendocrine dysregulation.

How Does the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Regulate Androgen Production?

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis serves as the central regulatory system for male reproductive and endocrine function. Its operation is a classic example of a negative feedback loop, ensuring precise control over hormone synthesis. The hypothalamus, a region of the brain, acts as the primary orchestrator, releasing gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in a pulsatile manner.

These pulses are critical; their frequency and amplitude dictate the downstream response. GnRH then travels to the anterior pituitary gland, stimulating specialized cells to synthesize and secrete two key gonadotropins ∞ luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

LH, upon reaching the testes, binds to specific receptors on the Leydig cells, initiating a cascade of intracellular events that culminate in testosterone synthesis from cholesterol. This process involves several enzymatic steps, including the rate-limiting conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone by the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1).

FSH, conversely, primarily targets the Sertoli cells within the seminiferous tubules, supporting spermatogenesis and the production of androgen-binding protein (ABP), which helps maintain high local testosterone concentrations necessary for sperm maturation.

The feedback mechanism completes the loop ∞ elevated levels of testosterone and its metabolite, estradiol, exert inhibitory effects on both the hypothalamus (reducing GnRH pulse frequency) and the pituitary (decreasing LH and FSH secretion). This sophisticated regulatory system ensures that testosterone levels are maintained within a narrow physiological range, adapting to the body’s needs while preventing overproduction. Disruptions at any point along this axis ∞ whether due to hypothalamic dysfunction, pituitary adenomas, or testicular failure ∞ can lead to hypogonadism.

The HPG axis orchestrates male hormonal balance through a precise feedback system, where disruptions at any level can lead to testosterone deficiency.

The Interplay of Metabolic Health and Testosterone Status

The relationship between testosterone and metabolic health is bidirectional and highly significant. Conditions such as obesity, insulin resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus are frequently associated with lower testosterone levels. Adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, is metabolically active and contains high levels of the aromatase enzyme. This enzyme converts testosterone into estradiol, thereby reducing circulating testosterone and potentially increasing estrogen levels in men. Elevated estrogen can further suppress LH secretion from the pituitary, exacerbating the testosterone deficiency.

Moreover, insulin resistance and chronic inflammation, common in metabolic syndrome, can directly impair Leydig cell function and reduce GnRH pulsatility. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ low testosterone contributes to increased fat mass and worsened insulin sensitivity, which in turn further suppresses testosterone production. Addressing metabolic health through lifestyle interventions, such as dietary modifications and increased physical activity, can therefore be a crucial component of managing hypogonadism, sometimes even improving testosterone levels without exogenous therapy in mild cases.

Consider the intricate connections between various systems ∞

- Adipose Tissue and Aromatase Activity ∞ Increased fat mass, especially visceral fat, leads to higher aromatase expression, converting testosterone to estrogen.

- Insulin Resistance and Leydig Cell Function ∞ Chronic hyperinsulinemia can directly impair the ability of Leydig cells to produce testosterone.

- Inflammation and HPG Axis Suppression ∞ Systemic inflammation, often present in metabolic syndrome, can suppress GnRH and LH secretion, disrupting the HPG axis.

- Sleep Apnea and Nocturnal Testosterone Release ∞ Obstructive sleep apnea, prevalent in obese individuals, disrupts sleep architecture and can significantly impair the nocturnal surge of testosterone, contributing to overall lower levels.

Advanced Considerations in Hypogonadism Diagnosis

Beyond the standard laboratory markers, advanced diagnostic considerations involve a deeper investigation into potential underlying etiologies. For instance, genetic conditions such as Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY karyotype) are a common cause of primary hypogonadism, characterized by small, firm testes, elevated gonadotropins, and low testosterone. Pituitary disorders, including prolactinomas (prolactin-secreting tumors) or other pituitary adenomas, can cause secondary hypogonadism by compressing or disrupting the normal function of gonadotroph cells, leading to low LH and FSH.

The impact of certain medications also warrants rigorous scrutiny. Long-term use of opioids, for example, is a well-documented cause of opioid-induced androgen deficiency, acting primarily by suppressing GnRH release. Glucocorticoids, used for various inflammatory conditions, can also suppress the HPG axis. A detailed medication history is therefore indispensable in the diagnostic process.

The concept of functional hypogonadism is also gaining recognition. This refers to a state of low testosterone driven by reversible factors such as chronic stress, excessive exercise without adequate recovery, severe caloric restriction, or critical illness. In these scenarios, addressing the underlying stressor or metabolic imbalance can often restore testosterone levels without the need for long-term hormonal optimization protocols.

This distinction is vital for guiding appropriate intervention strategies, emphasizing the body’s capacity for self-regulation when supportive conditions are provided.

The diagnostic criteria for low testosterone are not static; they represent a dynamic interplay of symptoms, biochemical markers, and underlying physiological context. A thorough evaluation demands a clinician’s ability to synthesize this information, identifying the specific type of hypogonadism and tailoring a management plan that addresses both the hormonal deficiency and any contributing systemic factors. This comprehensive approach moves beyond simple symptom management to a deeper recalibration of the body’s intricate systems, aiming for sustained vitality and optimal function.

References

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

- Boron, Walter F. and Emile L. Boulpaep. Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Mulligan, Thomas, et al. “Prevalence of Hypogonadism in Males Aged at Least 45 Years ∞ The HIM Study.” International Journal of Clinical Practice, vol. 60, no. 7, 2006, pp. 762-769.

- Traish, Abdulmaged M. et al. “The Dark Side of Testosterone Deficiency ∞ II. Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Resistance.” Journal of Andrology, vol. 30, no. 1, 2009, pp. 23-32.

- Yeap, Bu B. et al. “Testosterone and All-Cause Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer ∞ A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 99, no. 9, 2014, pp. 3085-3094.

- Zitzmann, Michael. “Testosterone Deficiency, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Syndrome.” Aging Male, vol. 16, no. 4, 2013, pp. 192-198.

Reflection

Understanding the diagnostic criteria for low testosterone is more than just learning about lab values; it is about gaining insight into the intricate workings of your own biological system. This knowledge serves as a powerful tool, enabling you to interpret the signals your body sends and to engage in meaningful conversations with healthcare professionals. The journey toward optimal hormonal health is deeply personal, requiring a partnership between your lived experience and clinical science.

What Does This Mean for Your Personal Health Trajectory?

The information presented here is a starting point, a framework for recognizing potential imbalances and appreciating the complexity of endocrine function. It highlights that symptoms are not isolated events but expressions of underlying physiological states. Taking this knowledge forward means recognizing that reclaiming vitality is an active process, one that involves careful assessment, informed decision-making, and a commitment to personalized wellness protocols.

Your body possesses an inherent intelligence, and by understanding its language, you hold the key to restoring its full functional capacity.