_

Fundamentals

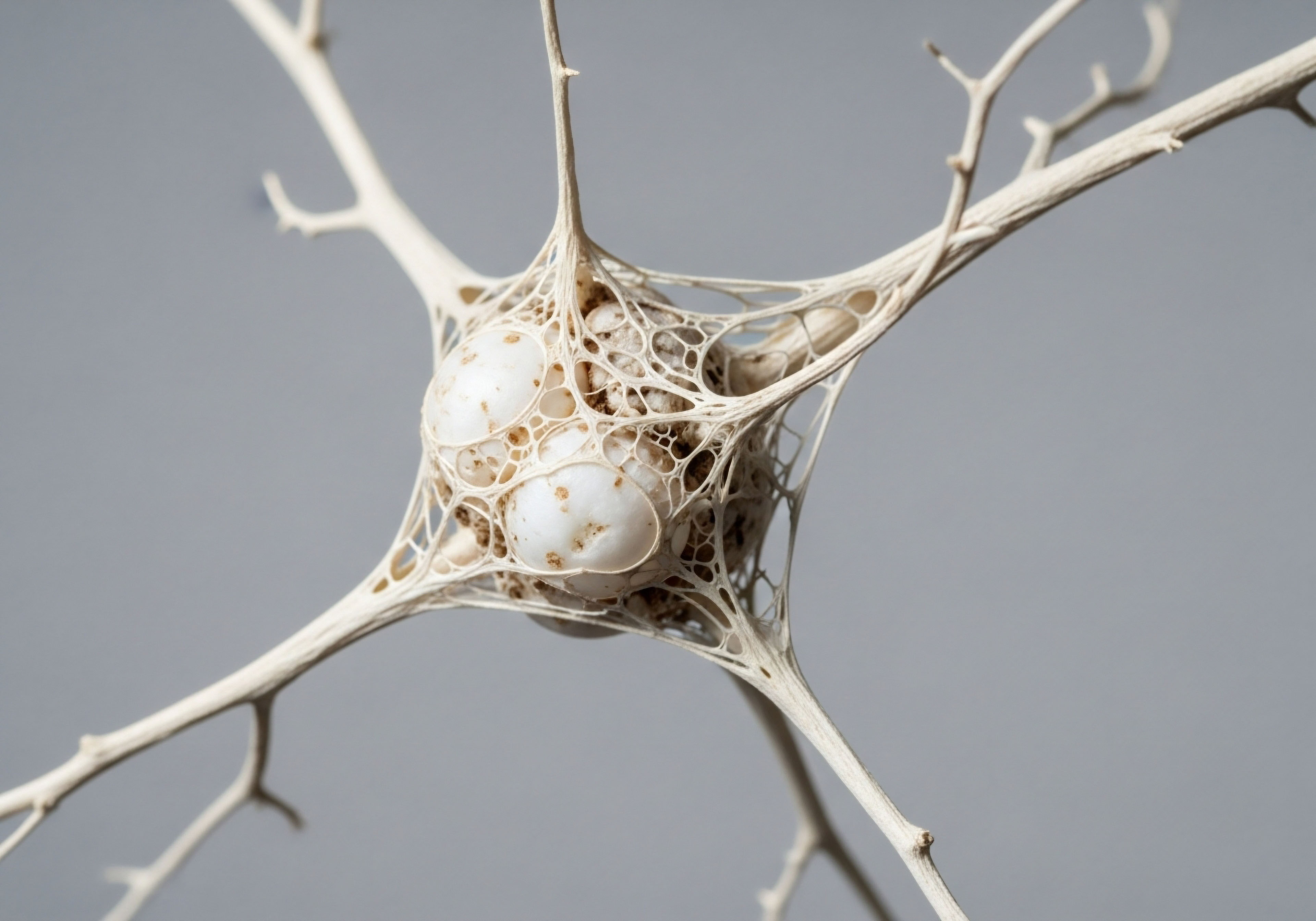

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in energy, a change in sleep quality, a frustrating plateau in your fitness ∞ these are the whispers of a system seeking equilibrium. Your body, a complex and interconnected network of hormonal signals, is constantly adapting.

When we discuss the unresolved issues in wellness program regulation, we are having a conversation about how to honor and support that biological reality within a corporate framework. At its heart, this is a deeply personal issue. It touches upon the delicate interplay between your autonomy and an employer’s intention to foster a healthy workforce.

The core of the matter lies in a concept known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the central command for your endocrine system, a continuous feedback loop connecting your brain to your reproductive organs. This system dictates everything from your stress response to your metabolic rate.

When a wellness program asks for your biometric data or encourages specific health outcomes, it is interacting with the downstream effects of this deeply personal biological system. The regulatory challenge is to create a framework that respects the sanctity of this internal environment while allowing for supportive, evidence-based health initiatives.

The Regulatory Void and Your Lived Experience

Imagine trying to navigate a complex landscape without a reliable map. This is the situation many employers and employees find themselves in today. Following the vacating of previous Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) rules, a definitive guide for what constitutes a lawful wellness program remains elusive.

This absence of a clear “safe harbor” means that the programs you encounter are designed under a cloud of legal uncertainty. For you, this translates into a wide variability in the quality, intrusiveness, and supportiveness of the wellness initiatives you are offered.

This regulatory ambiguity has profound implications for your personal health journey. It creates a space where well-intentioned programs can inadvertently cross ethical lines, and where your personal health data can become a commodity. The lack of clear guidance on issues like data privacy and non-discrimination means that the responsibility often falls on you to be a vigilant and informed participant in your own health, asking critical questions about how your information is being used and protected.

What Defines a Truly Voluntary Program?

A central question in this regulatory puzzle is the definition of “voluntary.” The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) mandate that any wellness program collecting health information must be voluntary. Yet, the concept of “voluntary” becomes complicated when substantial financial incentives are involved.

If declining to participate in a wellness program results in a significantly higher health insurance premium, is your choice truly free? This is a point of intense debate and a critical unresolved issue. The law struggles to draw a clear line between a gentle nudge and a form of coercion, leaving you to navigate this gray area.

The lack of clear federal guidance creates a confusing and inconsistent landscape for employer-sponsored wellness initiatives.

This tension between incentives and autonomy is more than a legal abstraction; it has a direct impact on your relationship with your health and your employer. It can create a dynamic where you feel pressured to disclose sensitive personal information, not for the sake of your own health journey, but to avoid a financial penalty.

This is a subtle but significant erosion of the trust that is essential for any truly effective wellness initiative. The unresolved nature of this issue means that the design of these programs can sometimes feel more transactional than transformational, focusing on participation metrics rather than your personal health outcomes.

Intermediate

To appreciate the depth of the regulatory challenges in workplace wellness, we must examine the specific legal and biological frameworks that intersect in this domain. The conversation moves beyond general principles of privacy and autonomy to the specific language of federal statutes and the intricate workings of human physiology. This is where the “Clinical Translator” voice becomes essential, bridging the gap between the legalese of regulatory bodies and the lived reality of your body’s endocrine system.

The central conflict arises from the collision of two powerful forces ∞ an employer’s desire to reduce healthcare costs and improve productivity, and the legal and ethical imperative to protect employees from discrimination and coercion. The regulations, or lack thereof, are the attempt to find a sustainable equilibrium between these two forces. Understanding this dynamic is key to understanding the unresolved issues that continue to challenge employers and employees alike.

The ADA, GINA, and the Elusive Definition of “voluntary”

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) form the primary legal guardrails for workplace wellness programs. The ADA restricts employers from making disability-related inquiries or requiring medical examinations, while GINA prohibits discrimination based on genetic information, including family medical history. Both statutes, however, contain exceptions for “voluntary” employee health programs. The ambiguity of “voluntary” is the crux of the regulatory problem.

The now-vacated 2016 EEOC rules attempted to clarify this by allowing for incentives of up to 30% of the cost of self-only health insurance coverage. This was challenged in court, with critics arguing that such a high incentive could be coercive, effectively forcing employees to disclose protected health information.

The subsequent proposal of “de minimis” incentives, such as a water bottle or a modest gift card, represented a significant shift in regulatory thinking, but these rules were also withdrawn. This leaves employers in a state of limbo, unsure of how to design a program that is both engaging and legally compliant.

| Incentive Type | Description | Potential Regulatory Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Participation-Based | Rewards for completing a health-related activity, such as a health risk assessment or biometric screening. | If the incentive is too high, it may be seen as coercive, undermining the “voluntary” nature of the program. |

| Outcome-Based | Rewards for achieving a specific health outcome, such as a certain cholesterol level or blood pressure reading. | This type of incentive faces greater scrutiny as it can be discriminatory against individuals with health conditions that make it difficult to achieve the desired outcome. |

| “De Minimis” | A small, token incentive, such as a water bottle or gift card of modest value. | While legally safer, this type of incentive may not be sufficient to drive employee engagement and participation in the program. |

The “reasonably Designed” Standard a Vague Mandate

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced the requirement that wellness programs be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” This standard, while well-intentioned, is frustratingly vague. It lacks the specific, measurable criteria that would allow employers to design programs with confidence and for employees to assess their quality. This ambiguity can lead to the proliferation of programs that are more focused on collecting data and checking boxes than on providing meaningful, evidence-based support for employee health.

The ongoing debate over incentive levels reflects a fundamental tension between encouraging participation and protecting employee autonomy.

This lack of a clear definition of “reasonably designed” has significant implications for the effectiveness of wellness programs. It can result in a focus on simplistic metrics, such as participation rates, rather than on long-term health outcomes.

For you, this can mean being subjected to programs that are poorly conceived, lack scientific rigor, and fail to address the root causes of health issues. It also creates a situation where it is difficult to hold programs accountable for their claims of improving employee health and well-being.

- Data Privacy and Security The increasing use of wearable technology and health apps in wellness programs raises significant privacy concerns. The data collected by these devices is often not protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and employees may not have a clear understanding of how their data is being collected, used, and secured.

- Discrimination and Equity There is a persistent concern that wellness programs can discriminate against employees with chronic health conditions, disabilities, or those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Outcome-based incentives, in particular, can penalize individuals for health factors that may be beyond their control.

- Efficacy and Return on Investment Despite the widespread adoption of wellness programs, the evidence for their effectiveness in improving health outcomes and reducing healthcare costs is mixed. Many studies on the topic are methodologically flawed, and there is a lack of long-term data to support the claims made by many wellness vendors.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the unresolved issues in wellness program regulation requires a multi-disciplinary approach, integrating principles of law, bioethics, and endocrinology. The current regulatory impasse is not merely a matter of legal interpretation; it is a reflection of a deeper societal struggle to reconcile the principles of individual autonomy with the goals of public health and corporate efficiency.

To fully grasp the complexities of this issue, we must move beyond a surface-level discussion of incentives and penalties and delve into the more profound questions of data ownership, algorithmic bias, and the very definition of “wellness” in a corporate context.

The central thesis of this academic exploration is that the current regulatory framework is fundamentally inadequate because it is based on an outdated and simplistic model of health and behavior. It fails to account for the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and socioeconomic factors that shape individual health outcomes. As a result, it creates a system that is prone to unintended consequences, including the exacerbation of health disparities and the erosion of employee trust.

The Tyranny of Wellness Algorithmic Bias and the Quantified Self

The proliferation of wearable technology and data analytics in workplace wellness has given rise to a new set of ethical challenges that the current regulatory framework is ill-equipped to address.

The data collected by these devices, while ostensibly used to promote health, can also be used to create detailed profiles of employees, which can then be used to make decisions about everything from insurance premiums to job assignments. This creates a significant risk of algorithmic bias, where employees are unfairly penalized for health conditions or lifestyle choices that are not fully within their control.

This “tyranny of wellness” can create a culture of surveillance and conformity, where employees feel pressured to conform to a narrow and often culturally biased definition of health. It can also lead to a focus on easily quantifiable metrics, such as steps taken or calories burned, at the expense of more holistic and meaningful measures of well-being, such as mental health and social connection.

The lack of specific regulations governing the use of this data creates a “Wild West” environment, where the potential for misuse is high.

Beyond HIPAA the Data Privacy Gap

A critical and often misunderstood aspect of wellness program regulation is the data privacy gap. Much of the health data collected by wellness programs, particularly through wearable devices and third-party apps, is not covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

This is because HIPAA’s privacy and security rules generally apply only to “covered entities” such as healthcare providers and health plans. Many wellness vendors fall outside of this definition, meaning that the sensitive health information they collect is not subject to the same stringent protections.

The absence of a robust regulatory framework for wellness data creates a significant risk of privacy violations and algorithmic discrimination.

This regulatory gap leaves employees vulnerable to a range of privacy harms, from the unauthorized disclosure of their health information to the use of their data for marketing and other commercial purposes. It also creates a situation where employees may be asked to consent to broad and often confusing privacy policies without fully understanding the implications.

The development of a more comprehensive data privacy framework for wellness programs is a critical unresolved issue that will require a coordinated effort from lawmakers, regulators, and employers.

| Regulation | Primary Jurisdiction | Applicability to Wellness Programs |

|---|---|---|

| HIPAA | Healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses. | Applies only to wellness programs that are part of a group health plan. Data collected by many third-party wellness vendors is not covered. |

| ADA | Employers with 15 or more employees. | Prohibits discrimination based on disability and requires that wellness programs be “voluntary.” |

| GINA | Employers with 15 or more employees. | Prohibits discrimination based on genetic information and restricts the collection of family medical history. |

| ACA | Group health plans and health insurance issuers. | Requires that wellness programs be “reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.” |

The future of wellness program regulation will require a paradigm shift, moving away from a focus on individual behavior change and toward a more holistic and systems-based approach. This will involve not only the development of more robust legal and ethical guidelines but also a deeper understanding of the social and economic determinants of health.

Ultimately, the goal should be to create a regulatory environment that fosters a culture of genuine well-being, one that respects the autonomy and dignity of every employee.

- The Need for a New Regulatory Paradigm The current patchwork of regulations is inadequate to address the complexities of modern wellness programs. A new, more comprehensive framework is needed, one that is grounded in the principles of bioethics and that takes into account the latest scientific evidence on health and behavior.

- The Importance of Independent Evaluation To ensure that wellness programs are both effective and ethical, they must be subject to rigorous, independent evaluation. This will require the development of standardized metrics and methodologies for assessing program outcomes, as well as greater transparency from wellness vendors.

- The Role of Employee Empowerment Ultimately, the success of any wellness program depends on the active and engaged participation of employees. This requires a shift away from a top-down, compliance-based approach and toward a more collaborative and empowering model, one that gives employees a meaningful voice in the design and implementation of the programs that affect them.

References

- Mello, M. M. & Rosenthal, M. B. (2016). Wellness programs and lifestyle discrimination ∞ the legal limits. New England Journal of Medicine, 374 (4), 301 ∞ 303.

- Madison, K. M. (2016). The ACA, workplace wellness programs, and the law. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 44 (1), 58 ∞ 61.

- Horwitz, J. R. & Kelly, B. D. (2017). Wellness programs, the ACA, and the EEOC ∞ What employers need to know. Benefits Law Journal, 30 (1), 3 ∞ 14.

- Jones, D. S. & McCullough, M. B. (2019). The ethical challenges of workplace wellness programs. AMA Journal of Ethics, 21 (3), 238 ∞ 245.

- Price, W. N. & Cohen, I. G. (2019). Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nature Medicine, 25 (1), 37 ∞ 43.

- Song, Z. & Baicker, K. (2019). Effect of a workplace wellness program on employee health and economic outcomes ∞ A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 321 (15), 1491 ∞ 1501.

- Ledger, A. & McCay, L. (2020). The ethics of workplace health promotion. Public Health Ethics, 13 (1), 1 ∞ 4.

- Appleby, J. & Thomas, C. (2021). Workplace wellness and the new regulatory landscape. Employee Relations Law Journal, 47 (2), 5 ∞ 15.

- Fisk, C. L. (2022). The quantified worker ∞ A critical analysis of workplace wellness programs in the age of surveillance capitalism. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law, 24 (3), 543 ∞ 598.

- Roberts, S. O. & Bareket-Bojmel, L. (2023). The double-edged sword of workplace wellness programs ∞ A review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44 (2), 256 ∞ 275.

Reflection

The journey to understanding your own biology is a profoundly personal one. The information presented here is designed to provide a framework for understanding the complex external landscape of wellness program regulation. Yet, the most important insights will come from within. How do these programs make you feel?

Do they empower you to take ownership of your health, or do they create a sense of pressure and surveillance? Your lived experience is the most valuable data point in this entire conversation.

As you move forward, consider this knowledge not as a set of definitive answers, but as a collection of well-informed questions. Use it to engage with your employer’s wellness initiatives in a more critical and constructive way. The ultimate goal is to find a path to well-being that is both evidence-based and authentic to you.

This is the true meaning of personalized wellness, a journey that begins with understanding the systems within you and the systems around you.