Fundamentals

The sense that your body is operating under a new set of rules, a subtle yet persistent deviation from the vitality you once knew, is a tangible experience. This internal shift, often characterized by a quiet erosion of energy, a change in physical form, or a muted sense of well-being, has its roots in the body’s intricate communication network.

The messengers in this system, your hormones, undergo a predictable, age-related recalibration. Understanding the clinical meaning of this process is the first step toward reclaiming your biological sovereignty.

Hormones are chemical signals that orchestrate countless physiological processes, from metabolic rate to cognitive function. Testosterone and estrogen, for instance, are primary architects of tissue integrity, influencing both muscle maintenance and bone density. Growth hormone (GH) acts as a master regulator of cellular repair and regeneration.

As we age, the production of these critical communicators naturally declines. This is a gradual process, a slow turning down of a dimmer switch rather than an abrupt power outage. The initial consequences are often felt subjectively before they are seen objectively. A pervasive feeling of fatigue, a less resilient mood, or the observation that body composition is changing despite consistent habits are the first whispers of this underlying endocrine transition.

The Tangible Effects of Hormonal Attenuation

The decline in hormonal signaling creates a cascade of interconnected effects. One of the most immediate and noticeable is the alteration of body composition. The body’s ability to synthesize new muscle protein diminishes, while its tendency to store adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat around the organs, increases.

This occurs because hormones like testosterone are potent anabolic signals, promoting the growth and repair of lean tissue. When these signals weaken, the body’s metabolic balance tips in favor of catabolism (breakdown) and fat storage. This is a foundational change that precedes more complex health issues.

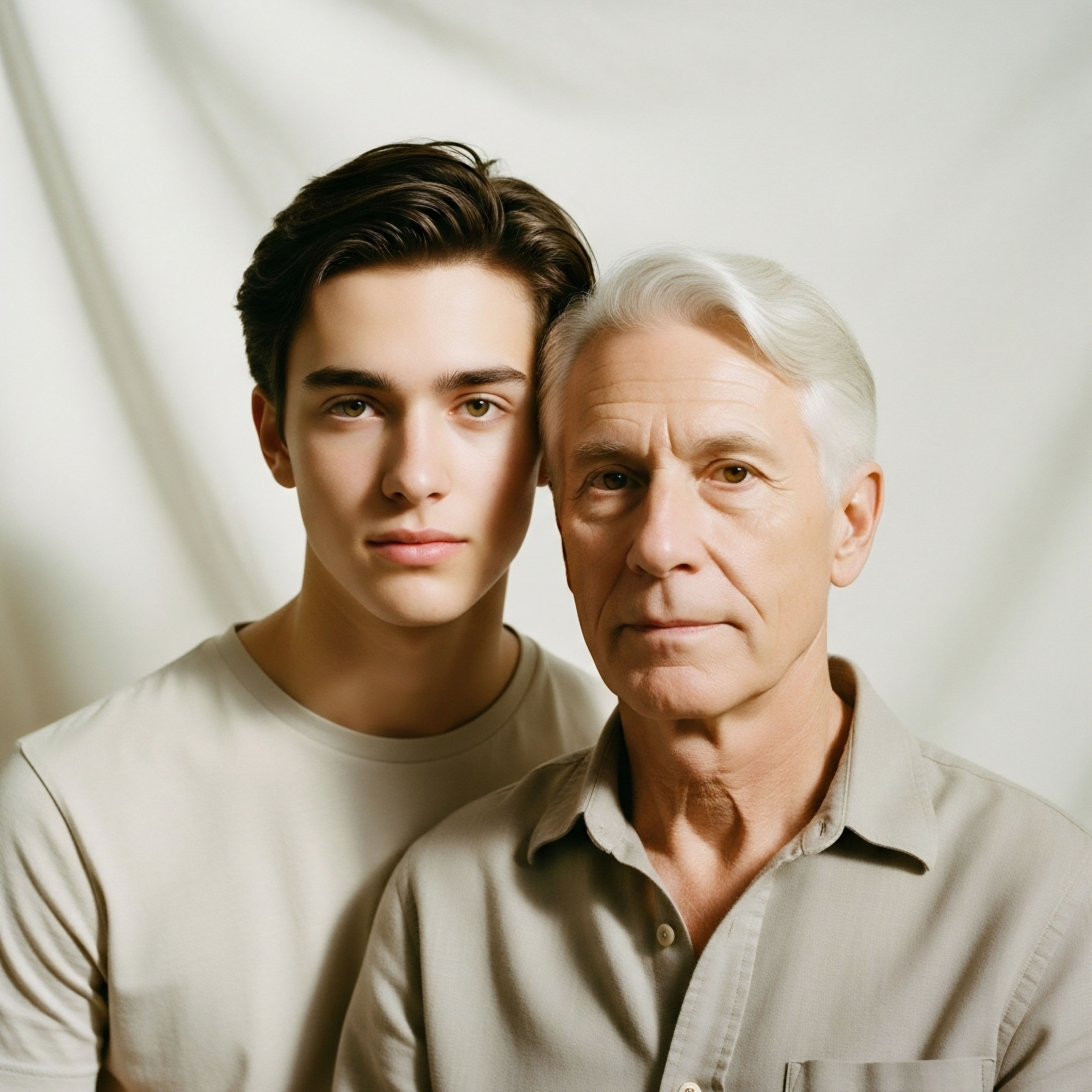

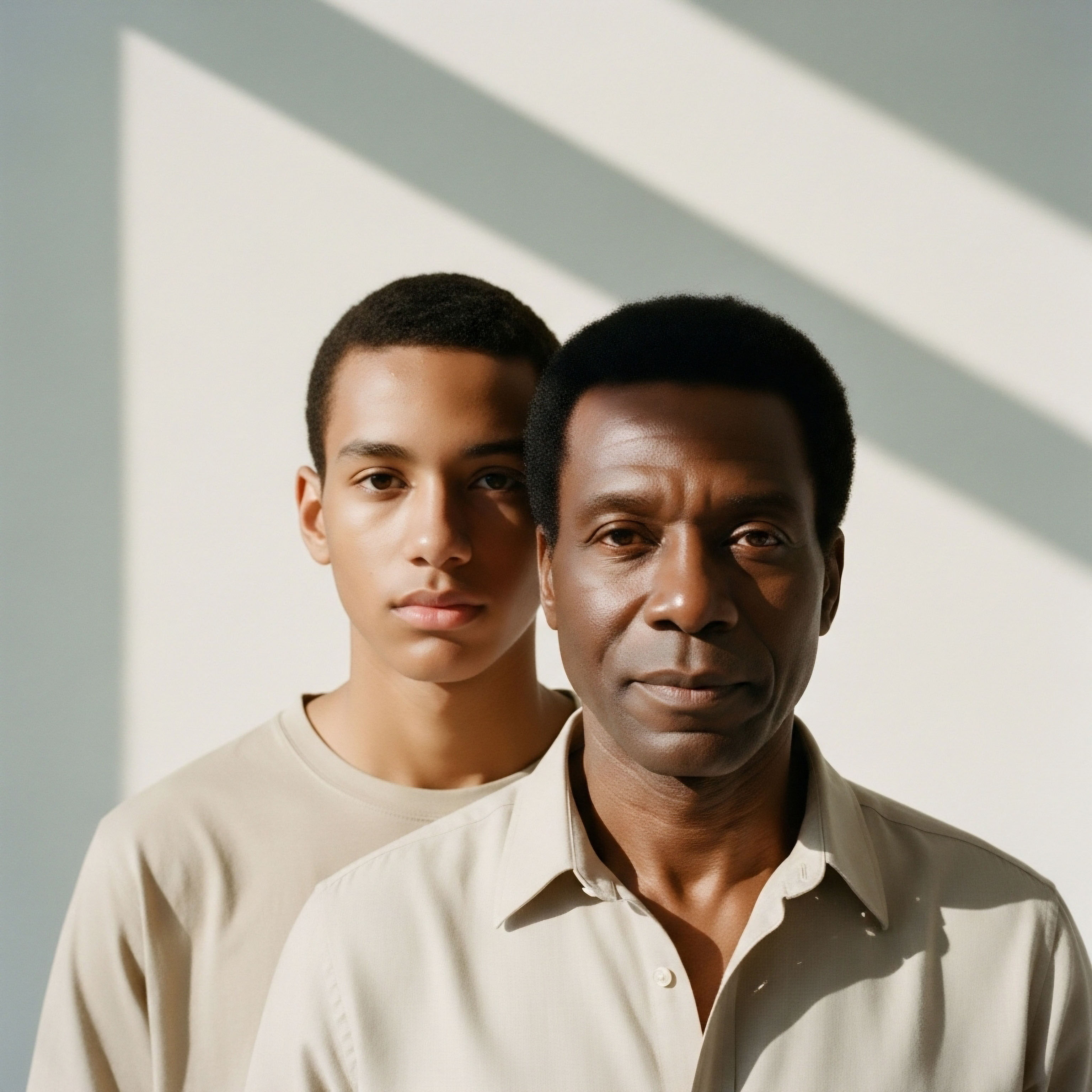

The gradual decline of key hormones initiates a systemic shift, impacting everything from energy levels and mood to the body’s fundamental composition of muscle and fat.

Simultaneously, bone health is directly impacted. Bone is a dynamic, living tissue that is constantly being broken down and rebuilt in a process called remodeling. Estrogen and testosterone play a direct role in regulating this balance, ensuring that bone formation keeps pace with resorption.

As levels of these hormones wane, the equilibrium shifts, leading to a net loss of bone mineral density. This process, known as osteopenia and its more advanced state, osteoporosis, unfolds silently over years, setting the stage for increased fracture risk in later life. These initial changes in muscle, fat, and bone represent the first clinical layer of ignoring age-related hormonal shifts, forming the bedrock upon which more serious conditions can develop.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the initial changes in body composition and energy, a more detailed examination reveals how attenuated hormonal signals disrupt the body’s most critical operating systems. The clinical implications of these disruptions extend into metabolic, musculoskeletal, and neurocognitive health, demonstrating a deeply interconnected web of physiological consequence. Ignoring these shifts means allowing systemic imbalances to become entrenched, potentially accelerating the aging process itself.

The relationship between hormonal status and metabolic function is particularly profound. Declining levels of testosterone in men and the shifting estrogen-progesterone balance in women are directly correlated with the onset of insulin resistance. Insulin, the hormone responsible for shuttling glucose from the bloodstream into cells for energy, becomes less effective.

The body’s cells grow deaf to its signal. This forces the pancreas to produce more insulin to achieve the same effect, a state known as hyperinsulinemia. This condition is a primary driver of visceral fat accumulation, hypertension, and dyslipidemia ∞ a collection of risk factors known as metabolic syndrome. The result is a significantly elevated risk for developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

How Does Hormonal Decline Affect Systemic Health?

The integrity of the musculoskeletal system, which provides the framework for all physical activity, is highly dependent on a robust endocrine environment. The age-related loss of muscle mass and function, termed sarcopenia, is directly accelerated by the decline in anabolic hormones like testosterone and growth hormone.

This process involves a reduction in the size and number of muscle fibers, leading to a measurable decrease in strength and physical capacity. The consequences extend beyond simple weakness; sarcopenia impairs balance, mobility, and the body’s ability to recover from injury or illness. It is a primary contributor to frailty and a loss of independence in older adults.

The following table outlines the parallel, yet distinct, symptomatic expressions of hormonal decline in men and women, illustrating the widespread impact of these changes.

| Symptom Category | Common Manifestations in Men (Andropause) | Common Manifestations in Women (Perimenopause/Menopause) |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic & Body Composition |

Increased visceral fat, decreased muscle mass, difficulty losing weight, emerging insulin resistance. |

Weight gain (especially abdominal), changes in fat distribution, hot flashes, night sweats, increased cardiovascular risk. |

| Psychological & Cognitive |

Decreased motivation and drive, low mood or irritability, ‘brain fog’, reduced focus. |

Mood swings, anxiety, depressive episodes, memory lapses, difficulty concentrating. |

| Physical & Vitality |

Pervasive fatigue, diminished physical stamina, longer recovery times from exercise. |

Sleep disturbances, chronic fatigue, joint pain, skin and hair changes. |

| Sexual Health |

Reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased spontaneous erections. |

Low libido, vaginal dryness, discomfort during intercourse. |

Neurocognitive and Sleep Architecture Disruption

The brain is a profoundly hormone-sensitive organ. The cognitive haze, memory lapses, and mood alterations that frequently accompany hormonal shifts are direct physiological manifestations. Hormones modulate the activity of key neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which regulate mood, motivation, and cognitive clarity.

Their decline can unbalance this delicate neurochemistry, contributing to feelings of depression or anxiety. Furthermore, sleep architecture is often disrupted. The age-related decline in growth hormone, which is secreted in pulses primarily during deep sleep, and the changes in sex hormones can lead to less restorative sleep. This creates a vicious cycle, as poor sleep further exacerbates hormonal imbalances and contributes to daytime fatigue and cognitive impairment.

A decline in hormonal signaling directly impairs metabolic efficiency, leading to insulin resistance and an elevated risk for chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular conditions.

Understanding these intermediate-level consequences reveals that ignoring hormonal shifts is tantamount to ignoring the body’s fundamental regulatory system. The symptoms are expressions of a deeper, systemic dysregulation that, left unaddressed, can significantly compromise long-term health and quality of life.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of age-related hormonal decline moves beyond a catalog of symptoms to an examination of the central control mechanisms themselves. The clinical implications at this level are understood as a failure in the body’s complex biofeedback systems.

The primary locus of this age-related dysregulation is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis for sex hormones and the parallel Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Somatotropic (HPS) axis for growth hormone. A failure to address these shifts is, in essence, permitting the degradation of the body’s master regulatory architecture.

The classic model of aging often points to peripheral organ failure, for instance, the ovaries ceasing egg production in menopause or a gradual decline in testicular Leydig cell function in andropause. A more precise view reveals a concurrent and perhaps primary failure in the central command centers.

In aging men, for example, low serum testosterone is met with an inappropriately muted response from the pituitary gland. Instead of a robust increase in Luteinizing Hormone (LH) to stimulate the testes, studies show that aging is associated with reduced LH pulse amplitude and a more disorderly secretion pattern.

This points to an age-associated impairment of the hypothalamic Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) pulse generator itself. The system loses its sensitivity and precision, a condition of central origin compounding the peripheral decline.

What Is the Role of Central Biofeedback Loop Failure?

The age-related decline in the growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis, a state termed somatopause, provides another clear example of central dysregulation. GH is secreted in a pulsatile manner by the pituitary, under the dual control of hypothalamic GHRH (stimulatory) and somatostatin (inhibitory).

Aging is associated with a decreased secretion of GHRH and a potential enhancement of somatostatin’s inhibitory tone. The result is a significant drop in GH pulses, particularly the large nocturnal pulse associated with deep sleep and cellular repair. This GH decline directly causes a reduction in the liver’s production of IGF-1, the primary mediator of GH’s anabolic effects on peripheral tissues. The clinical consequences are systemic, contributing directly to sarcopenia, decreased bone density, impaired immune function, and altered lipid metabolism.

The core issue of hormonal aging lies in the degradation of central feedback loops within the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, leading to a systemic loss of regulatory precision.

The following table details the key players in the HPG axis and the documented changes that occur with advancing age, illustrating the multi-level nature of the dysregulation.

| Axis Component | Primary Function | Documented Age-Related Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamus |

Secretes Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in pulses to stimulate the pituitary. |

Evidence suggests a reduction in GnRH pulse generator frequency and amplitude, leading to less precise signaling. |

| Pituitary Gland |

Responds to GnRH by secreting Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). |

Shows a blunted response to GnRH. LH pulses become smaller and more irregular, failing to adequately stimulate the gonads. |

| Gonads (Testes/Ovaries) |

Produce testosterone (testes) or estrogen/progesterone (ovaries) in response to LH and FSH. |

Intrinsic decline in function and hormone output. Ovaries undergo follicular depletion; testes show reduced Leydig cell capacity. |

| Systemic Effect |

Hormones regulate metabolism, bone density, muscle mass, and cognitive function. |

A state of relative hormone deficiency develops, which is inadequately compensated for by the central control system. |

The Inflammatory Cascade and Cellular Senescence

The downstream effect of this central and peripheral hormonal decline is the promotion of a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. Sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen have immunomodulatory properties, helping to restrain pro-inflammatory cytokine activity. Their decline is associated with an increase in inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6).

This systemic inflammation acts as a powerful accelerator of age-related diseases, contributing to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative conditions, and metabolic syndrome. It creates a cellular environment that is less resilient and more prone to dysfunction. This biochemical milieu, born from endocrine failure, becomes a foundational contributor to the multi-system morbidity that characterizes unaddressed hormonal aging.

The following list outlines key physiological systems and the direct impact of ignoring hormonal shifts:

- Cardiovascular System ∞ Declining estrogen and testosterone are linked to endothelial dysfunction, adverse lipid profiles, and an increased risk of atherosclerotic plaque formation.

- Central Nervous System ∞ Hormonal support is critical for neuronal health, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter balance. Its absence contributes to cognitive decline and mood disorders.

- Metabolic System ∞ A loss of hormonal regulation over glucose and lipid metabolism is a primary driver of insulin resistance, visceral obesity, and type 2 diabetes.

- Musculoskeletal System ∞ Anabolic hormonal signals are required to maintain the structural integrity of bone and muscle, and their absence leads directly to osteoporosis and sarcopenia.

References

- Varlamov, Oleg, et al. “The Role of Androgens and Estrogens on Healthy Aging and Longevity.” The Journals of Gerontology ∞ Series A, vol. 77, no. 5, 2022, pp. 929-940.

- Fui, Mark Ng, et al. “Hormonal and Metabolic Changes of Aging and the Influence of Lifestyle Modifications.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 19, 2022, p. 11844.

- Morley, John E. “Andropause ∞ Clinical Implications of the Decline in Serum Testosterone Levels With Aging in Men.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A ∞ Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, vol. 57, no. 2, 2002, pp. M76-M99.

- Garrido-Cumbrera, Marco, et al. “Age-Related Hormones Changes and Its Impact on Health Status and Lifespan.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2021, 2021, Article ID 9954708.

- Al-Zoubi, Raed M. et al. “Andropause ∞ A Neglected Disease Entity.” OBM Geriatrics, vol. 7, no. 3, 2023, pp. 1-20.

Reflection

A Personal Biological Narrative

The information presented here forms a clinical map, tracing the origins of felt experiences back to their biological roots. This knowledge transforms abstract feelings of decline into a series of understandable, interconnected physiological events. It provides a new lens through which to view your own health narrative.

The journey from recognizing symptoms to understanding systems is the foundational step. The path forward involves asking how this map applies to your unique physiology, a question that begins a proactive and deeply personal dialogue with your own body. What does your individual story of change tell you, and what will your next chapter be?

Glossary

growth hormone

body composition

visceral fat

hormones like testosterone

hormonal shifts

osteoporosis

insulin resistance

metabolic syndrome

sarcopenia

hormonal decline

andropause