Fundamentals

You may feel that your body is operating on a script you never consented to, with energy levels, mood, and physical well-being fluctuating in ways that seem disconnected from your daily choices. The experience of hormonal imbalance is deeply personal, a persistent and often frustrating conversation happening within your own physiology.

The path to understanding this internal dialogue begins with recognizing that you have a direct line of communication to the systems that govern it. That line of communication is, in large part, the food you consume, and specifically, the dietary fats that form the very foundation of your hormonal architecture.

Your body does not interpret dietary fat merely as a source of calories to be burned or stored. It sees fat as a collection of raw materials and potent signaling molecules. These molecules are the literal building blocks for some of the most powerful chemical messengers in your system.

Gaining a deep appreciation for this process is the first step toward reclaiming a sense of agency over your own biological processes. It allows you to move from feeling like a passenger in your own body to becoming an informed participant in your health.

The Architectural Role of Fats in Hormonal Production

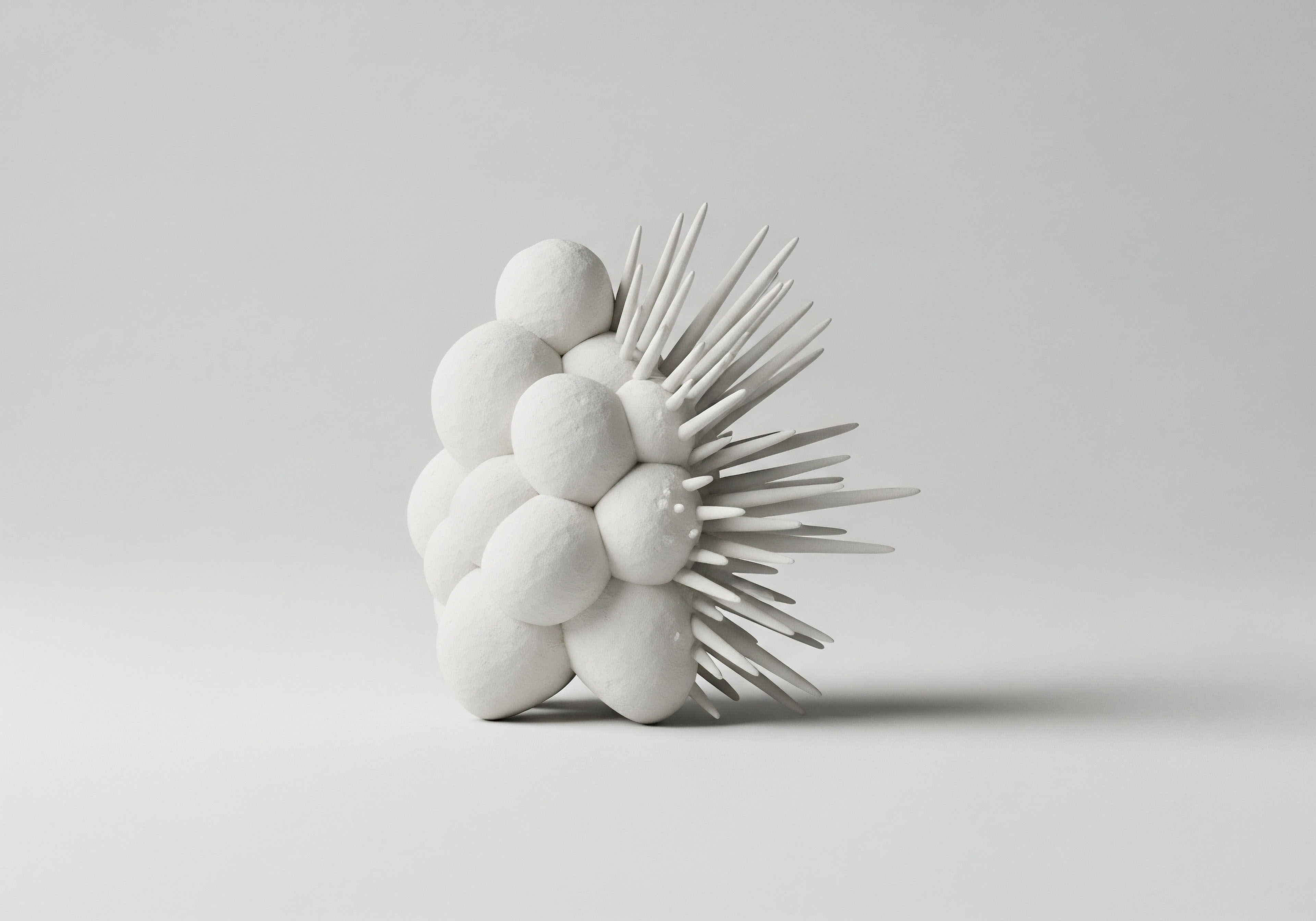

At the very center of hormonal health lies a single, waxy substance that is often misunderstood ∞ cholesterol. Every steroid hormone in your body, which includes cortisol (the primary stress hormone), aldosterone (which regulates blood pressure), and all of your sex hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone, is synthesized from cholesterol.

Your body can produce its own cholesterol, and it also absorbs it from dietary sources. The fats you eat directly influence your body’s lipid profile, which includes the cholesterol available for this essential manufacturing process. An imbalance in dietary fat intake, such as an extremely low-fat diet, can limit the availability of this foundational precursor, potentially compromising the entire steroid hormone production line.

Think of your endocrine system as a highly sophisticated factory. Cholesterol is the primary raw material delivered to the factory floor. From this single starting point, a series of enzymatic steps, like specialized workers on an assembly line, modify the cholesterol molecule to produce different hormonal outputs.

A deficiency in the primary raw material means the factory cannot meet its production quotas, leading to systemic effects. A diet severely lacking in healthy fats can therefore create a bottleneck in this critical biological process, impacting everything from your stress response to your reproductive health.

Cellular Gatekeepers How Fats Influence Hormone Sensitivity

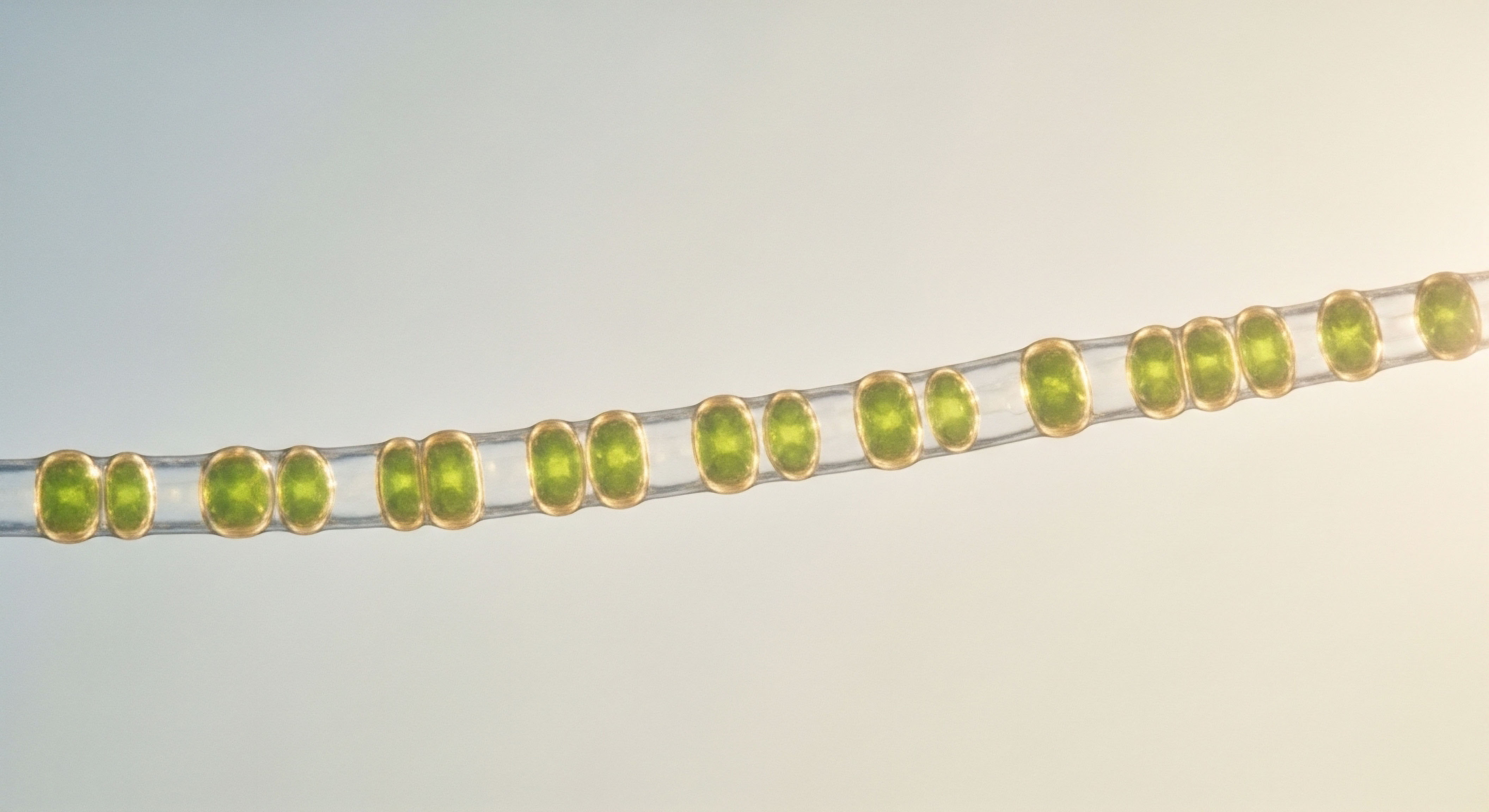

Beyond being simple building blocks, dietary fats play a dynamic role in how your cells listen and respond to hormonal signals. Every cell in your body is encased in a membrane composed of a lipid bilayer. This membrane is not a static wall; it is a fluid, active surface embedded with receptors that act as docking stations for hormones.

The composition of this membrane is directly influenced by the types of fats you consume. A diet rich in fluid, flexible unsaturated fats, such as omega-3s, creates a cell membrane that is supple and responsive. This allows hormone receptors to move freely and function optimally, ensuring that hormonal messages are received loud and clear.

Conversely, a diet high in certain saturated fats and man-made trans fats can lead to a cell membrane that is stiff and rigid. This rigidity can impair the function of hormone receptors, effectively muffling the hormonal conversation. The hormone might be present in the bloodstream, but the cell cannot properly receive its message.

This phenomenon is a key component of what is known as hormone resistance, most famously seen in insulin resistance, where cells become less responsive to the signal of insulin. The fats you eat are therefore determining the quality of communication at a cellular level, influencing whether your body’s intricate hormonal signals are effectively translated into biological action.

Dietary fats are not just fuel; they are the foundational molecules from which your body constructs its most vital hormonal messengers.

Understanding this dual role of fats, as both architectural precursors and dynamic modulators of cellular communication, provides a powerful new framework for considering your dietary choices. Each meal is an opportunity to provide your body with the high-quality materials it needs to build, regulate, and maintain its own sophisticated systems.

This perspective shifts the focus from simple calorie counting to a more profound appreciation for the quality of information you are giving your body to work with. It is the beginning of a collaborative partnership with your own physiology, aimed at restoring function and vitality from the inside out.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of fats as building blocks, we can begin to appreciate their role within the body’s complex regulatory networks. Your endocrine system operates through a series of sophisticated feedback loops, primarily governed by two central command centers ∞ the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, which manages your stress response, and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, which orchestrates reproductive health.

The quality and balance of dietary fats you ingest directly influence the function of these command centers, affecting the clarity of the signals they send and the sensitivity of the tissues that receive them. An imbalance in dietary fat is not a passive issue; it actively disrupts these communication pathways, leading to clinical consequences that manifest as tangible symptoms.

The HPG Axis a System Sensitive to Lipid Signals

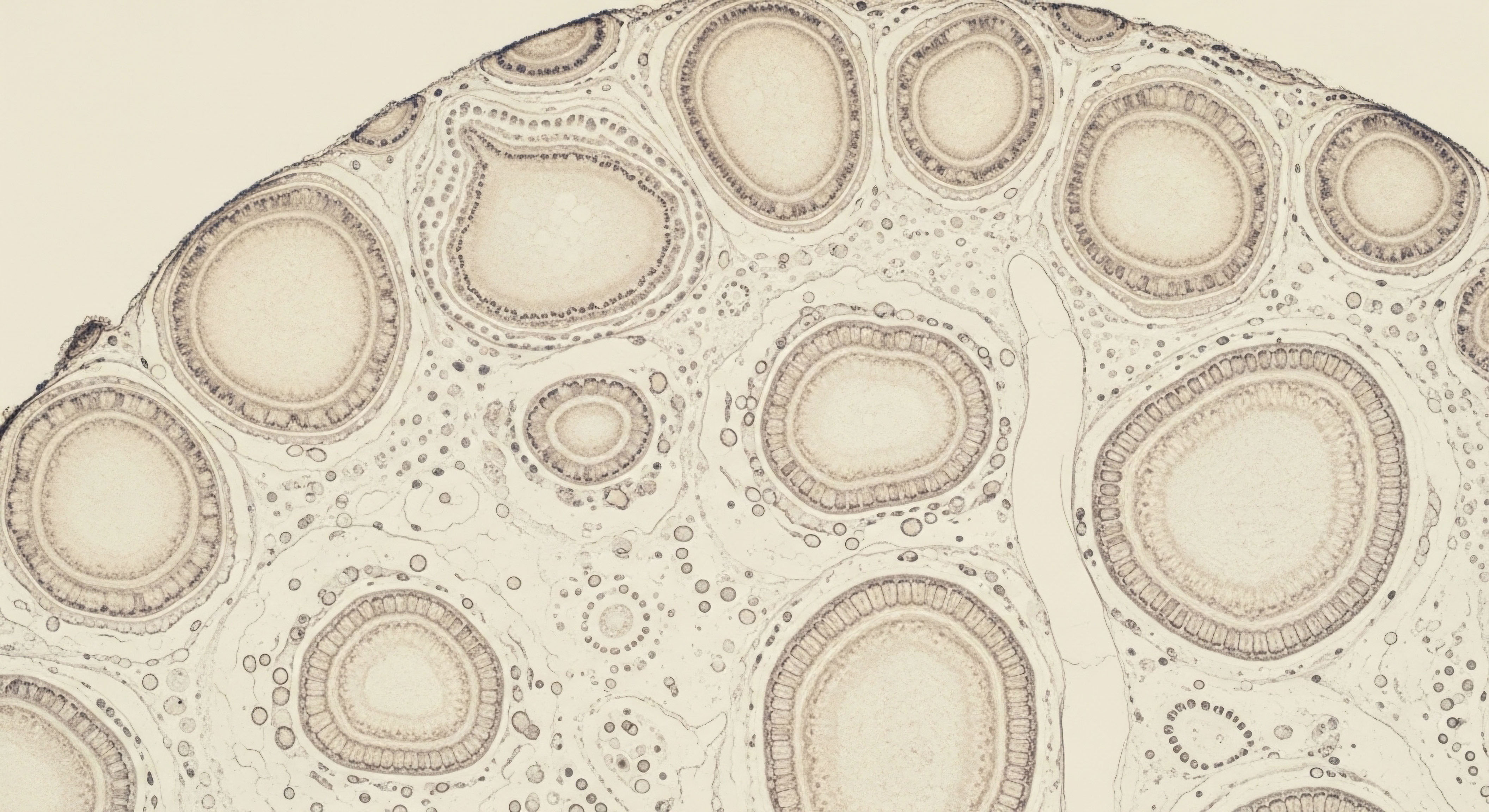

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis is the hormonal cascade that regulates sexual development and reproductive function. It begins in the brain, where the hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This signal travels to the pituitary gland, prompting it to release Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH).

These hormones then travel to the gonads (testes in men, ovaries in women) to stimulate the production of testosterone and estrogen, respectively. The levels of these sex hormones in the blood are monitored by the hypothalamus, which adjusts its GnRH output accordingly, creating a self-regulating loop.

Dietary fat imbalances can disrupt this axis at multiple points. For instance, in men, obesity driven by high-fat, high-calorie diets is strongly associated with secondary hypogonadism. The excess adipose tissue becomes a significant site of aromatase activity, an enzyme that converts testosterone into estradiol.

This elevation in estradiol sends a powerful negative feedback signal to the hypothalamus and pituitary, telling them to reduce the output of GnRH and LH. The result is a diminished signal to the testes to produce testosterone, creating a vicious cycle where low testosterone further encourages fat accumulation. Providing the body with a balanced fat profile, particularly one that does not promote excess adiposity, is therefore integral to maintaining the integrity of this male reproductive axis.

In women, the HPG axis is similarly vulnerable. The delicate pulsatile release of GnRH required for a regular menstrual cycle can be disrupted by the metabolic stress associated with dietary fat imbalance. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), a common endocrine disorder in women, is a prime example.

PCOS is often characterized by insulin resistance, which is exacerbated by diets high in saturated and trans fats. The resulting high levels of insulin can directly stimulate the ovaries to produce excess androgens (like testosterone), disrupting follicular development and ovulation. Furthermore, supplementation with specific polyunsaturated fats, like omega-3s, has been shown to reduce bioavailable testosterone in women with PCOS, suggesting a direct modulatory role for certain fats in recalibrating this system.

Insulin and Leptin the Metabolic Messengers

The conversation between dietary fats and hormonal health extends deeply into metabolic regulation, primarily through the hormones insulin and leptin. Insulin’s job is to manage blood glucose, but its function is profoundly affected by the lipid environment. Diets high in saturated fats can contribute to a state of insulin resistance, where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signal.

To compensate, the pancreas produces more and more insulin, a condition known as hyperinsulinemia. This state of high insulin has cascading effects on other hormonal systems, including the HPG axis, as seen in PCOS.

Leptin is the “satiety hormone,” produced by fat cells to signal to the brain that energy stores are sufficient. In a balanced system, this helps regulate appetite. However, in the context of obesity driven by dietary fat imbalance, the brain can become resistant to leptin’s signal.

Despite having very high levels of leptin, the brain doesn’t get the message to stop eating. This leptin resistance also disrupts the HPG axis, as the hypothalamus requires clear leptin signaling to properly regulate GnRH release. The type of fat matters here as well. Polyunsaturated fats, especially omega-3s, can help improve insulin and leptin sensitivity, while high intakes of saturated fats can worsen resistance.

The balance of dietary fats directly informs the body’s central hormonal command centers, influencing everything from reproductive cycles to metabolic stability.

How Different Fats Send Different Signals

To translate this into practical application, it is helpful to categorize dietary fats by their primary signaling tendencies. While all fats have overlapping roles, their dominant effects on hormonal pathways can be distinguished.

- Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs) ∞ Found in animal fats, butter, and tropical oils like coconut and palm oil. While necessary in moderation for cholesterol production and cell structure, excessive intake is linked to increased LDL cholesterol, promotion of insulin resistance, and a pro-inflammatory state. They can contribute to the hormonal disruptions seen in obesity and metabolic syndrome.

- Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs) ∞ The primary fat in olive oil, avocados, and many nuts. MUFAs are generally associated with improved insulin sensitivity and a better cholesterol profile. They are a cornerstone of the Mediterranean diet, a dietary pattern linked to better hormonal and metabolic health.

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) ∞ This class includes omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Their balance is what is most important.

- Omega-6 PUFAs ∞ Abundant in many vegetable oils (like soybean, corn, and sunflower oil) and processed foods. While essential, the typical Western diet provides an excessive amount relative to omega-3s. High levels can lead to the production of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules.

- Omega-3 PUFAs ∞ Found in fatty fish (EPA, DHA), flaxseeds, and walnuts (ALA). These fats are precursors to powerful anti-inflammatory molecules. They have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce androgen levels in women with PCOS, and support overall cellular health.

- Trans Fatty Acids ∞ These are primarily artificially created fats found in processed and fried foods. They have no known beneficial role and are strongly linked to insulin resistance, inflammation, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. They are uniquely disruptive to hormonal signaling.

The table below summarizes the primary clinical implications of an imbalance favoring certain types of fats.

| Fat Type | Primary Hormonal Influence | Associated Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fats (in excess) | Promotes insulin resistance; can increase aromatase activity in obesity. | Worsening of PCOS symptoms; contributes to low testosterone in men; increases low-grade inflammation. |

| Monounsaturated Fats | Improves insulin sensitivity; supports healthy cholesterol levels. | Associated with better metabolic health; protective component of the Mediterranean diet. |

| Omega-6 PUFAs (in excess) | Precursor to pro-inflammatory eicosanoids. | Can drive chronic low-grade inflammation, which underlies many hormonal dysfunctions. |

| Omega-3 PUFAs | Precursor to anti-inflammatory eicosanoids; improves cell membrane fluidity. | May lower androgens in PCOS; improves insulin sensitivity; supports HPG axis function. |

| Trans Fats | Induces significant insulin resistance and inflammation. | Strongly linked to metabolic syndrome; disrupts cellular communication and overall hormonal balance. |

Understanding these distinctions empowers you to make dietary choices that send the right signals to your body. It is a process of recalibrating the system by providing the appropriate balance of fatty acids required for clear communication and optimal function. This approach moves beyond simple dietary restriction and toward a model of targeted nutritional support for your entire endocrine system.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of the clinical implications of dietary fat imbalance requires moving beyond systemic descriptions to the precise molecular interfaces where fats and their metabolites regulate hormonal function. The core of this interaction lies in the ability of fatty acids to act as ligands for nuclear receptors and to modulate the enzymatic pathways of steroidogenesis.

This section will detail the mechanisms through which polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), in particular, exert control over gene expression via Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) and influence the synthesis of steroid hormones by regulating key enzymes and precursor availability. This molecular perspective illuminates how dietary choices translate into the profound physiological and pathological states observed clinically.

PUFAs as Direct Modulators of Nuclear Receptor Activity

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) are a group of nuclear receptor proteins that function as transcription factors to regulate the expression of genes. They are central to the metabolism of lipids and carbohydrates, inflammatory responses, and cellular differentiation. There are three main isoforms ∞ PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ/β.

Fatty acids and their derivatives, especially PUFAs, are the natural ligands for these receptors. When a fatty acid binds to a PPAR, the receptor undergoes a conformational change, forms a heterodimer with the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR), and binds to specific DNA sequences known as Peroxisome Proliferator Response Elements (PPREs) in the promoter region of target genes. This action directly alters the rate of transcription for those genes.

This mechanism is a direct line of communication from diet to DNA. For example:

- PPARα ∞ Abundantly expressed in the liver, heart, and muscle, PPARα is primarily activated by both n-3 and n-6 PUFAs. Its activation promotes the transcription of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation (beta-oxidation), effectively increasing the burning of fat for energy. This is a key mechanism by which PUFAs can improve lipid profiles and reduce the lipid accumulation that contributes to insulin resistance.

- PPARγ ∞ Highly expressed in adipose tissue, PPARγ is a master regulator of adipogenesis (the creation of fat cells) and is potently activated by certain PUFA metabolites. Its activation improves insulin sensitivity by promoting the storage of fatty acids in adipose tissue, thus preventing their accumulation in other organs like the liver and muscle where they can cause lipotoxicity and insulin resistance. The action of PPARγ is so central to insulin sensitivity that the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of diabetes drugs are synthetic PPARγ agonists. Dietary PUFAs function as natural modulators of this same pathway.

The differential activation of PPARs by various fatty acids explains many of the clinical observations related to dietary fat. The anti-inflammatory effects of n-3 PUFAs, for instance, are partly mediated by their ability to activate PPARs, which can then repress the expression of pro-inflammatory genes like TNF-α and IL-6.

Since chronic low-grade inflammation is a key driver of hormonal dysregulation in conditions like PCOS and obesity-related hypogonadism, the ability of dietary fats to quell this inflammation at the genetic level is of immense clinical importance.

Regulation of Steroidogenesis and Sex Hormone Bioavailability

Dietary fats influence the production and bioavailability of sex hormones through several distinct mechanisms, extending beyond the simple provision of the cholesterol backbone.

First, the balance of PUFAs influences the local production of eicosanoids, which are potent signaling molecules derived from fatty acids. Arachidonic acid (an omega-6 PUFA) is the precursor to prostaglandins like PGE2, which can have pro-inflammatory effects and influence steroidogenic processes in the gonads.

Conversely, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, an omega-3 PUFA) is a precursor to prostaglandins like PGE3, which are less inflammatory. This balance can therefore modulate the microenvironment of the ovaries and testes, impacting the efficiency of hormone production.

Second, dietary fat intake has been shown to modulate the concentrations of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), a protein produced by the liver that binds to sex hormones in the bloodstream, rendering them inactive. Only the “free,” unbound hormone can exert a biological effect.

High-carbohydrate, low-fat diets are often associated with lower levels of SHBG, which increases the proportion of free testosterone and estrogen. Conversely, diets with a healthier fat profile can support SHBG production. In conditions like PCOS, where high insulin levels suppress SHBG production, dietary interventions that improve insulin sensitivity via fat modification can help increase SHBG, thereby lowering the amount of bioactive free androgens.

Fatty acids function as direct transcriptional regulators, binding to nuclear receptors to alter the genetic expression of metabolic and inflammatory pathways.

A 2016 study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition provided specific evidence of these connections in healthy, regularly menstruating women. The research demonstrated that higher total fat intake, and PUFA intake specifically, was associated with small but statistically significant increases in total and free testosterone concentrations.

This suggests a direct influence on steroidogenesis or SHBG levels. More strikingly, the intake of a specific marine n-3 PUFA, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), was associated with a significantly lower risk of anovulation. This finding points toward a specific role for certain fatty acids in supporting the complex sequence of events required for successful ovulation, possibly through the modulation of progesterone production or follicular health.

The table below presents a summary of key research findings illustrating the impact of specific dietary fat interventions on hormonal parameters, drawing from the evidence base.

| Study Focus | Dietary Intervention | Key Hormonal/Clinical Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCOS and PUFAs | Supplementation with long-chain n-3 PUFAs. | Reduced bioavailable testosterone concentrations in women with PCOS. | |

| Healthy Women’s Cycles | Higher dietary intake of total fat and PUFAs. | Associated with small increases in total and free testosterone. | |

| Healthy Women’s Cycles | Higher dietary intake of docosapentaenoic acid (n-3 DPA). | Associated with increased progesterone and a reduced risk of anovulation. | |

| Obesity and Weight Loss | Caloric restriction leading to weight loss in obese women. | Significant decrease in free testosterone and LH levels, with increased ovulation frequency. | |

| Obesity and Men | High-fat diets contributing to obesity. | Increased aromatase activity, leading to higher estrogen and lower testosterone (secondary hypogonadism). | |

| Metabolic Health | High saturated fat intake. | Linked to hyperinsulinemia and development of insulin resistance. |

In summary, the clinical implications of dietary fat imbalance are the macroscopic manifestation of millions of molecular interactions. The specific fatty acid profile of a person’s diet directly informs the transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes through PPARs and other factors. It simultaneously modulates the enzymatic pathways of steroidogenesis and influences the bioavailability of active hormones through proteins like SHBG.

This intricate, multi-layered influence solidifies the role of dietary fat as a primary and powerful tool in the clinical management of hormonal health. An evidence-based dietary protocol, therefore, is one that is designed to provide the specific lipid signals required to resolve inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and support balanced hormone production at the most fundamental levels.

References

- Mazza, Elisa, et al. “Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Hormonal Balance Modulation ∞ Gender-Specific Impacts.” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 11, 2024, p. 1629.

- Phelan, N. et al. “Hormonal and metabolic effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome ∞ results from a cross-sectional analysis and a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 93, no. 3, 2011, pp. 652-662.

- “The Relationship Between Fats and Hormones.” Allara Health, 15 May 2025.

- Mumford, Sunni L. et al. “Dietary fat intake and reproductive hormone concentrations and ovulation in regularly menstruating women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 103, no. 3, 2016, pp. 868-877.

- “Obesity and hormones.” Better Health Channel, Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Australia, 2016.

- Hagerty, M. A. et al. “Effect of low- and high-fat intakes on the hormonal milieu of premenopausal women.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 47, no. 4, 1988, pp. 653-658.

- Ingram, D. M. et al. “Effect of low-fat diet on female sex hormone levels.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 79, no. 6, 1987, pp. 1225-1229.

- Storlien, L. et al. “Does Dietary Fat Influence Insulin Action?” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 827, no. 1, 1997, pp. 287-301.

Reflection

Recalibrating Your Internal Conversation

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory, detailing the profound connections between what you eat and how your body communicates with itself. This knowledge is designed to be a tool for empowerment, a way to translate feelings of frustration or confusion about your body into a clear, actionable understanding of its inner workings.

The journey to hormonal balance is a personal one, and this map is a starting point, not a final destination. Consider your own dietary patterns. What signals have you been sending to your body? What raw materials have you been providing for its essential work? Reflecting on these questions is the first step in a more conscious, collaborative relationship with your own physiology, a path toward restoring the vitality that is your birthright.

Glossary

dietary fats

dietary fat

hormonal health

sex hormones

dietary fat intake

cell membrane

saturated fats

trans fats

where cells become less responsive

insulin resistance

testosterone

estrogen

secondary hypogonadism

aromatase

polycystic ovary syndrome

hpg axis

women with pcos

cells become less responsive

leptin resistance

fatty acids

insulin sensitivity

polyunsaturated fatty acids

omega-3 fatty acids

improve insulin sensitivity

clinical implications

steroidogenesis

improves insulin sensitivity

pufa

free testosterone

total and free testosterone

clinical nutrition