Fundamentals

The experience of participating in a wellness program while managing a thyroid disorder can feel like being asked to run a race with an anchor tied to your ankle. You see the track, you understand the goal, and you expend immense effort, yet your results seem stubbornly disconnected from your commitment.

This feeling of being penalized arises from a fundamental misalignment. Corporate wellness incentives are typically built upon a standardized model of human metabolism, one that assumes a predictable relationship between calories, activity, and outcomes like body weight or Body Mass Index (BMI).

Your biology, governed by a dysregulated thyroid system, operates under a completely different set of rules. The penalties you may face are not a reflection of your effort; they are a direct consequence of a system measuring a reality that is not your own.

Understanding this disconnect begins with appreciating the thyroid gland’s role as the master regulator of your body’s metabolic engine. Imagine your metabolism as a complex furnace, responsible for generating the energy every single cell in your body needs to function.

The thyroid gland, a small, butterfly-shaped organ at the base of your neck, acts as the thermostat for this furnace. It produces two primary hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which travel through the bloodstream and instruct your cells on how fast to burn fuel.

T3 is the more potent, active form of the hormone, and much of the less active T4 is converted into T3 within the body’s tissues. This entire process is orchestrated by the brain, specifically the pituitary gland, which releases Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) to tell the thyroid how much hormone to produce. It is a delicate and responsive feedback loop designed to maintain perfect energy balance.

A thyroid disorder fundamentally alters the body’s metabolic rate, making standardized wellness metrics an inaccurate measure of an individual’s health efforts.

When a person has hypothyroidism, the most common form of thyroid disorder, this system is compromised. The thyroid gland fails to produce enough T4 and T3, causing the pituitary to release more and more TSH in a futile attempt to stimulate it.

This state is akin to turning the thermostat up, but the furnace is unable to respond. The biological consequences are systemic and profound. The basal metabolic rate (BMR), which is the amount of energy your body burns at rest, slows down considerably. This is a central reason why standard “calories in, calories out” models fail.

A person with an untreated or undertreated thyroid condition requires significantly fewer calories to maintain their weight compared to someone with a healthy thyroid. The excess energy is readily stored as fat, leading to weight gain or an intractable difficulty in losing weight, even with stringent dieting and exercise. This is not a matter of willpower; it is a matter of cellular mechanics.

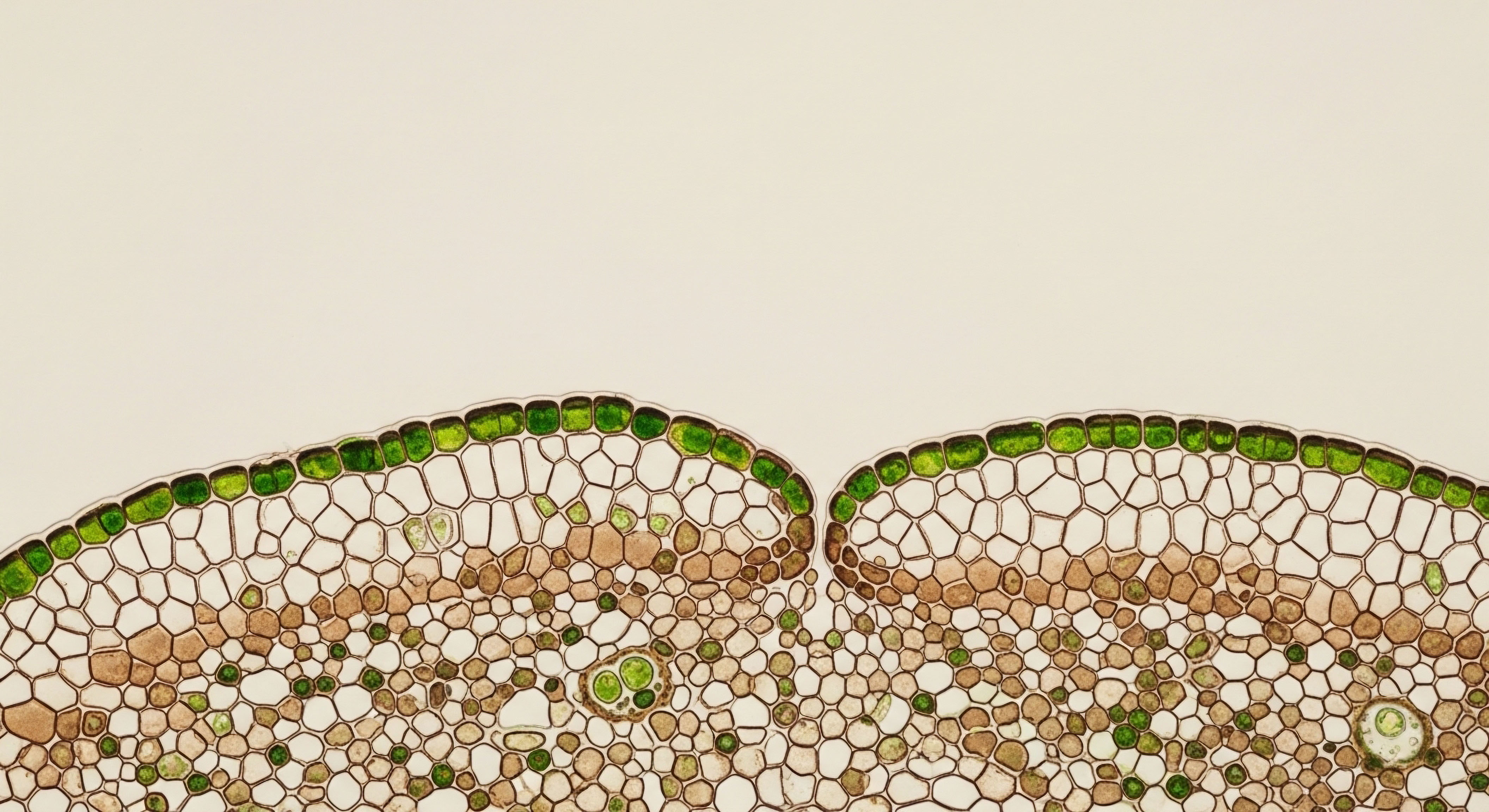

Furthermore, the weight gain associated with hypothyroidism is compositionally distinct. A significant portion of the initial increase on the scale is due to widespread fluid retention, a condition known as myxedema. The hormones T4 and T3 are essential for maintaining the proper balance of water and salt in the body’s tissues.

When they are deficient, substances called glycosaminoglycans accumulate in the interstitial spaces between cells, particularly in the skin and muscles. These molecules attract and hold water, leading to puffiness, swelling, and a form of weight gain that has nothing to do with fat accumulation. Wellness programs, which often rely on simple scale weight or BMI, cannot distinguish between fat mass and this metabolically-driven fluid retention, unfairly penalizing the individual for a biological process entirely outside of their control.

The Invisible Barriers to Participation

Beyond the direct impact on weight and metabolism, thyroid dysfunction creates a cascade of symptoms that erect formidable, often invisible, barriers to meeting the activity-based goals of many wellness programs. These programs frequently incentivize metrics like step counts, gym check-ins, or participation in fitness challenges. For a person with a healthy endocrine system, these are matters of scheduling and motivation. For someone with a thyroid disorder, they are challenges of physiological capacity.

Systemic Fatigue and Energy Depletion

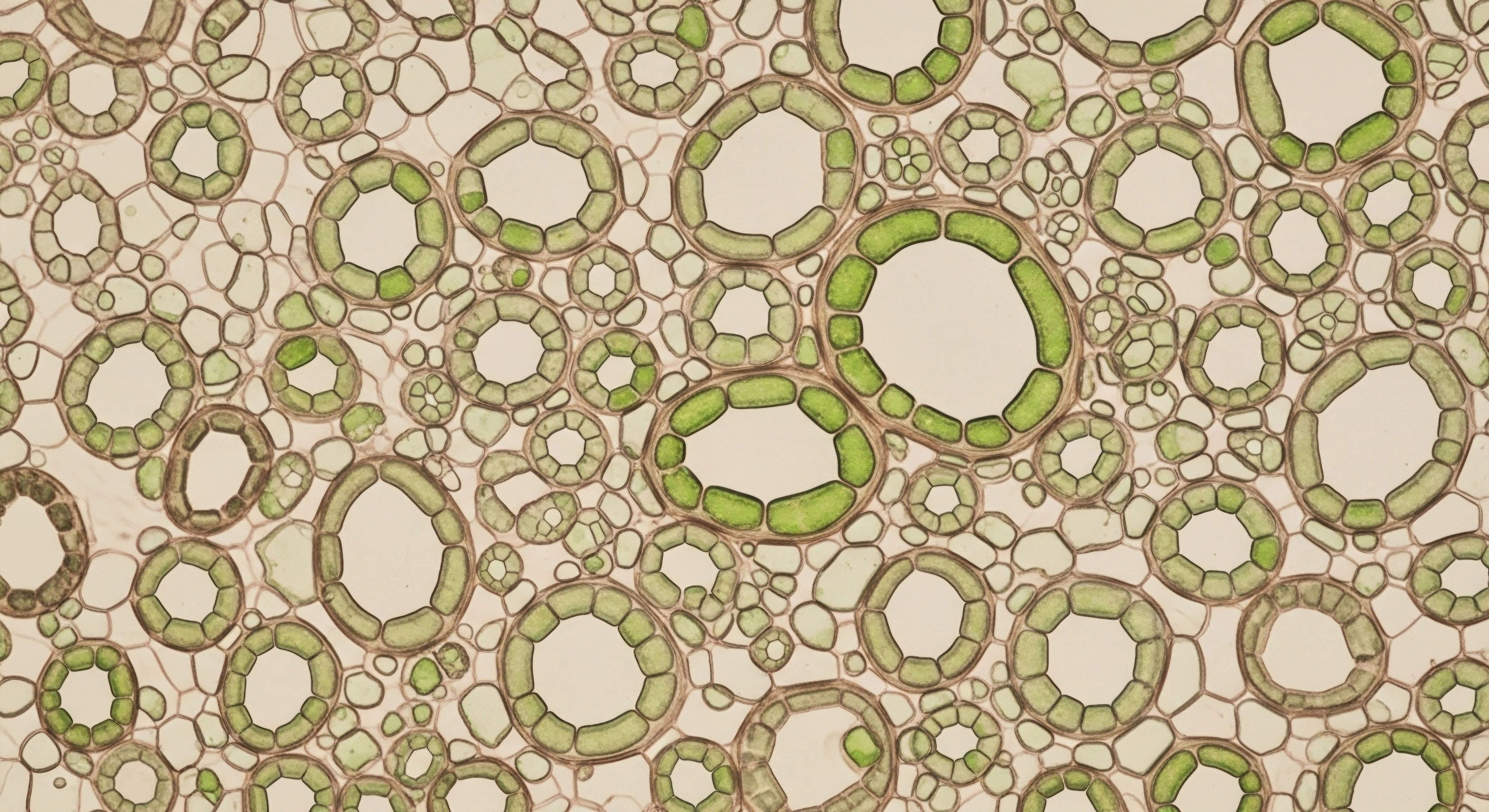

Profound fatigue is a hallmark symptom of hypothyroidism. This is a direct result of the body’s slowed metabolic engine. At a cellular level, the mitochondria, the tiny powerhouses within our cells, are not receiving the hormonal signal to produce energy at a normal rate.

The result is a pervasive exhaustion that is not relieved by sleep. It is a bone-deep weariness that can make the very thought of a workout, or even a brisk walk, feel insurmountable. While a wellness program may see a missed gym session as a lack of commitment, the biological reality is a body that is in a state of profound energy conservation, unable to generate the surplus energy required for vigorous physical activity.

Musculoskeletal Impact

Thyroid hormones are also crucial for muscle and joint health. In a hypothyroid state, individuals often experience muscle weakness, aches, and prolonged recovery times after exercise. This occurs because the slowed metabolism impairs the muscles’ ability to repair themselves and clear metabolic byproducts. Joint pain and stiffness are also common complaints.

These physical limitations make high-impact activities difficult and painful, pushing individuals toward a more sedentary state as a protective measure. A wellness incentive that rewards high-intensity interval training or running challenges completely overlooks the biological reality that such activities could be detrimental for someone whose musculoskeletal system is already compromised by their condition.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational understanding of a slowed metabolism reveals a more intricate web of biological dysregulation that explains why individuals with thyroid disorders struggle against the metrics of conventional wellness incentives. The penalties they incur are rooted in the complex interplay between thyroid hormones, energy utilization at the cellular level, and the body’s systems for managing fuel, stress, and recovery.

The issue is one of efficiency and communication. A healthy body is an efficient engine; a body with a thyroid disorder is an engine struggling with poor fuel quality, a faulty ignition, and a compromised cooling system.

One of the most significant, yet often overlooked, factors is the impact of thyroid hormone deficiency on mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are the engines within every cell, responsible for converting glucose and fatty acids into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal currency of energy.

Thyroid hormone, specifically T3, acts as a primary regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (the creation of new mitochondria) and their respiratory efficiency. When T3 levels are low, this process is severely blunted. The number of mitochondria per cell can decrease, and the remaining ones become less effective at producing ATP.

This directly translates to the profound fatigue and exercise intolerance experienced by individuals with hypothyroidism. A wellness program that rewards strenuous activity is asking a body with a depleted cellular power grid to handle a massive energy surge, a request that is physiologically impossible to meet and can lead to debilitating post-exertional malaise.

How Does Thyroid Function Affect Metabolic Flexibility?

A healthy metabolism possesses a quality known as “metabolic flexibility,” the ability to efficiently switch between burning carbohydrates and fats for fuel depending on their availability. This flexibility is crucial for maintaining stable energy levels, managing weight, and recovering from exercise. Thyroid hormones are key conductors of this metabolic orchestra. They influence the expression of genes involved in both glycolysis (the breakdown of glucose) and beta-oxidation (the breakdown of fatty acids).

In a hypothyroid state, this flexibility is lost. The body’s ability to tap into fat stores for energy is significantly impaired. Instead, it becomes more reliant on glucose, which can lead to cravings for carbohydrates and an increased propensity to store any unused energy as fat.

This metabolic inflexibility creates a frustrating paradox ∞ the very activities designed to burn fat are less effective, and the body’s response to dietary changes is sluggish and unpredictable. An individual might follow the prescribed diet and exercise plan of a wellness program with meticulous care, yet their body, locked in a state of metabolic rigidity, cannot produce the expected results. The penalty they receive is for a lack of biological adaptability, a direct symptom of their underlying condition.

The metabolic rigidity imposed by a thyroid disorder directly undermines the body’s ability to respond to the diet and exercise stimuli central to wellness programs.

This issue is compounded by the development of insulin resistance. While often associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance is a common feature in hypothyroidism. Thyroid hormones and insulin have a synergistic relationship in regulating glucose uptake by cells. When thyroid hormone levels are low, the sensitivity of cells to insulin decreases.

This means the pancreas must produce more insulin to get glucose out of the bloodstream and into the cells for energy. Chronically high insulin levels are a powerful signal for the body to store fat, particularly visceral fat around the organs.

This creates a vicious cycle ∞ the thyroid disorder promotes insulin resistance, which in turn promotes fat storage and makes weight loss even more challenging. A wellness program’s BMI or waist circumference metric penalizes the individual for a hormonal cascade that is actively working against their efforts.

The Interplay of Thyroid and Adrenal Systems

No endocrine gland operates in isolation. The thyroid has an intimate and critical relationship with the adrenal glands, which manage the body’s stress response through the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. A poorly functioning thyroid gland is a significant physiological stressor, placing a chronic burden on the adrenal system. This can lead to dysregulation of cortisol, the primary stress hormone.

In the initial stages, the body may produce excessive cortisol to compensate for the lack of energy and inflammation associated with the thyroid condition. High cortisol can lead to further increases in blood sugar, cravings for high-calorie foods, and the deposition of central adipose tissue.

Over time, this chronic demand can lead to a blunted cortisol response, often referred to as HPA axis dysfunction or “adrenal fatigue.” This state is characterized by extreme exhaustion, a poor response to stress, and difficulty recovering from any form of exertion.

An individual in this state attempting to follow a demanding wellness program schedule is, in a biological sense, pushing a system that is already running on empty. The result is not improved fitness, but a deeper state of exhaustion and potential worsening of their overall condition.

The following table illustrates the conflicting realities between a standard wellness program expectation and the biological state of an individual with hypothyroidism:

| Wellness Program Metric/Expectation | Biological Reality in Hypothyroidism |

|---|---|

| Consistent Weight Loss (e.g. 1-2 lbs/week) | Reduced Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) and fluid retention make this target biologically unrealistic. The body is primed for energy storage, not expenditure. |

| Increased Activity Levels (e.g. 10,000 steps/day) | Profound cellular fatigue, muscle weakness, and joint pain create significant barriers to physical activity. Pushing through can lead to prolonged recovery times. |

| Improved Body Composition (Lower BMI/Body Fat %) | Metabolic inflexibility and insulin resistance promote fat storage and inhibit fat burning, directly opposing this goal. Fluid retention can also artificially inflate BMI. |

| Participation in High-Intensity Challenges | Impaired mitochondrial function and HPA axis dysregulation mean the body lacks the capacity for high-energy output and efficient recovery. |

The Limitations of Standard Treatment

A common misconception is that once a person with hypothyroidism begins treatment, typically with levothyroxine (a synthetic T4 hormone), all these biological issues resolve, and they should be able to perform like anyone else. While treatment is essential and life-saving, it is often an imperfect solution.

Standard protocols aim to normalize serum TSH levels, but this does not always translate to optimal thyroid hormone activity in all the tissues of the body. The conversion of inactive T4 to active T3 can be impaired by factors like stress, nutrient deficiencies, and inflammation, all of which are common in individuals with thyroid disorders.

This means a person can have “normal” lab results yet still suffer from persistent symptoms of hypothyroidism at a cellular level. They may feel better than they did before treatment, but their metabolic machinery is still not functioning at 100%.

Expecting them to meet the same wellness benchmarks as a person with a natively healthy endocrine system is to ignore this crucial clinical subtlety. They are being judged against a standard of health their biology, even when medically supported, may not be able to achieve.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of the conflict between thyroid disorders and wellness incentive programs requires moving beyond systemic effects into the realm of cellular and molecular biology. The fundamental penalty imposed by these programs is a failure to recognize that hypothyroidism, even when treated to achieve a “normal” serum TSH, does not guarantee euthyroidism at the tissue level.

The biological reasons for this discrepancy are intricate, involving the nuanced regulation of thyroid hormone transport into the cell, the tissue-specific activity of deiodinase enzymes, and the integrity of nuclear thyroid hormone receptors. It is within this microscopic landscape that the true, and often invisible, disadvantages lie.

The journey of a thyroid hormone from the bloodstream to its ultimate destination ∞ the cell nucleus where it regulates gene expression ∞ is a complex and highly regulated process. Serum levels of T4 and T3 provide an incomplete picture.

Specific transmembrane transporter proteins, such as Monocarboxylate Transporter 8 (MCT8) and Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptides (OATPs), are required to shuttle T4 and T3 across the cell membrane. The expression and activity of these transporters can vary significantly between tissues and can be influenced by genetic factors, inflammation, and metabolic state.

A person may have sufficient hormone circulating in their blood, but if the transport machinery into key metabolic tissues like skeletal muscle or the liver is compromised, they will experience a state of localized, or tissue-specific, hypothyroidism. Wellness incentives, blind to this cellular reality, measure the output of a system (e.g. muscle performance, fat metabolism) without accounting for a critical bottleneck in its supply chain.

What Is the Role of Deiodinase Enzymes in Metabolic Control?

The conversion of the relatively inactive prohormone T4 into the biologically potent T3 is the critical activation step for thyroid hormone. This conversion is not a random event; it is meticulously controlled by a family of three selenoenzymes known as deiodinases (D1, D2, and D3), each with a distinct tissue distribution and regulatory function. The activity of these enzymes is arguably more important for metabolic control than the raw amount of circulating T4.

- Deiodinase 1 (D1) ∞ Primarily located in the liver, kidneys, and thyroid gland, D1 is responsible for a significant portion of circulating T3. Its activity is decreased in states of caloric restriction and systemic illness, representing an adaptive mechanism to conserve energy.

- Deiodinase 2 (D2) ∞ This is the key enzyme for local T3 production within specific tissues, including the brain, pituitary gland, brown adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle. D2 is the “smart” enzyme, allowing individual cells to fine-tune their own metabolic rate. For example, in skeletal muscle, D2 activity is crucial for regulating mitochondrial function and thermogenesis. Polymorphisms in the DIO2 gene have been linked to poorer psychological well-being and impaired T4-to-T3 conversion, particularly in patients on levothyroxine monotherapy.

- Deiodinase 3 (D3) ∞ As the primary inactivating enzyme, D3 converts T4 to reverse T3 (rT3) and T3 to T2, effectively acting as a brake on thyroid hormone signaling. Its expression is increased during states of severe stress, inflammation, and catabolism, a condition known as Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome (NTIS) or Euthyroid Sick Syndrome.

A person with a thyroid disorder, particularly one accompanied by the chronic inflammation characteristic of autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, may have altered deiodinase activity. They might exhibit increased D3 activity and decreased D2 activity, shunting T4 away from active T3 and towards the inactive rT3.

The result is a cellular environment starved of active thyroid hormone, despite a serum TSH and T4 level that may be within the therapeutic range. This individual will experience the full spectrum of hypothyroid symptoms ∞ fatigue, cognitive slowing, impaired exercise capacity ∞ because their muscle and brain cells are functionally hypothyroid. A wellness program, with its reliance on external performance metrics, is fundamentally incapable of detecting this state of cellular energy crisis and penalizes the person for its inevitable consequences.

Cellular hypothyroidism, driven by impaired hormone transport and deiodinase activity, creates a profound disconnect between normalized lab values and an individual’s actual metabolic capacity.

Genomic Action and Non-Genomic Effects

Once inside the cell and converted to T3, the hormone must bind to Thyroid Hormone Receptors (TRs), specifically TRα and TRβ, located in the cell nucleus. This hormone-receptor complex then binds to Thyroid Hormone Response Elements (TREs) on DNA, initiating the transcription of a vast array of genes that control metabolism, development, and cellular differentiation.

The number and sensitivity of these receptors can be downregulated by chronic inflammation or other metabolic signals, further dampening the thyroid signal even in the presence of adequate T3.

The following table details the tissue-specific consequences of impaired local T3 regulation, a critical factor overlooked by wellness programs.

| Affected Tissue | Mechanism of Impairment | Consequence for Wellness Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle | Reduced D2 activity, leading to lower intracellular T3. This impairs mitochondrial respiration and expression of genes for muscle protein synthesis. | Decreased strength, endurance, and recovery. Inability to meet exercise intensity or duration goals. Higher perceived exertion for a given workload. |

| White Adipose Tissue (WAT) | Altered expression of TRs and deiodinases affects lipolysis (fat breakdown) and adipokine secretion (e.g. leptin). | Inhibited fat burning and increased fat storage. Leptin resistance can develop, disrupting appetite signals and further promoting weight gain. |

| Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT) | D2 is essential for activating Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1) in BAT, the primary mechanism for non-shivering thermogenesis (heat production). | Reduced thermogenesis and a lower overall daily energy expenditure. A biological predisposition to feeling cold and conserving calories. |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) | MCT8 transporters and D2 activity in the brain are critical for maintaining local T3 levels, which regulate neurotransmitter systems (serotonin, dopamine). | Cognitive fog, depression, and lack of motivation (“anhedonia”), which directly impact the psychological drive to engage in wellness activities. |

This systems-level view demonstrates that a thyroid disorder is a pervasive disruption of cellular energy economics. The penalties incurred in a wellness program are not simply due to a “slow metabolism” in a general sense. They are the cumulative result of impaired hormone transport, tissue-specific enzymatic dysfunction, and blunted genomic signaling.

These factors create a biological reality where the effort-to-result ratio is fundamentally skewed. An individual may exert twice the effort for half the result compared to a metabolically healthy peer, not due to a lack of adherence, but due to a cascade of molecular inefficiencies.

Wellness incentives that use a single, uniform yardstick for a biologically diverse population are not just unfair; they are scientifically unsound, punishing individuals for a physiological state that is beyond the reach of willpower.

References

- S. B. Pearce, S. H. S. Pearce, and S. B. Pearce, “Hypothyroidism and obesity ∞ An intriguing link,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 11, pp. 4345 ∞ 4353, 2013.

- G. L. P. M. de Lacerda, J. H. Romaldini, and R. S. S. de Lacerda, “Relationship between thyroid dysfunction and body weight ∞ a not so evident paradigm,” Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia, vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 617-624, 2014.

- G. I. M. Pérez-Guisado, J. Pérez-Guisado, and J. M. Pérez-Guisado, “Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Patients with Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome ∞ A Narrative Review,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 134, 2024.

- R. G. D. Singh, A. K. Singh, and R. K. Singh, “Influence of Exercise on Oxygen Consumption, Pulmonary Ventilation, and Blood Gas Analyses in Individuals with Chronic Diseases,” Medical Sciences, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 1, 2024.

- American Diabetes Association. “Diabetes Care.” American Diabetes Association, 2024.

Reflection

Recalibrating the Definition of Success

The information presented here offers a biological counter-narrative to the often-simplistic story told by wellness programs. It validates the profound sense of injustice felt when immense personal effort fails to align with prescribed benchmarks. This knowledge is the first step in shifting your perspective.

Your body is not a failed project; it is a complex, responsive system operating under a unique set of physiological rules dictated by your endocrine health. The true measure of wellness is not found on a standardized leaderboard, but in the personal, incremental progress of understanding and supporting your own intricate biology.

This journey is about recalibrating your definition of success, moving away from external validation and toward a deep, internal appreciation for your body’s resilience. The path forward involves using this understanding as a tool for self-advocacy, fostering a partnership with healthcare providers who see beyond the numbers, and cultivating a form of well-being that is authentic to your own biological reality.

Glossary

thyroid disorder

wellness program

wellness incentives

thyroid gland

tsh

hypothyroidism

basal metabolic rate

weight gain

fluid retention

wellness programs

thyroid hormones

individuals with thyroid disorders

thyroid hormone

insulin resistance

adipose tissue

hpa axis

levothyroxine

deiodinase enzymes

skeletal muscle