Fundamentals

The experience of noticing subtle shifts in cognitive sharpness, memory recall, or even the quality of your sleep as you age is a deeply personal and often disquieting one. You may observe a word that is suddenly just out of reach, or a feeling of mental fog that descends without a clear cause.

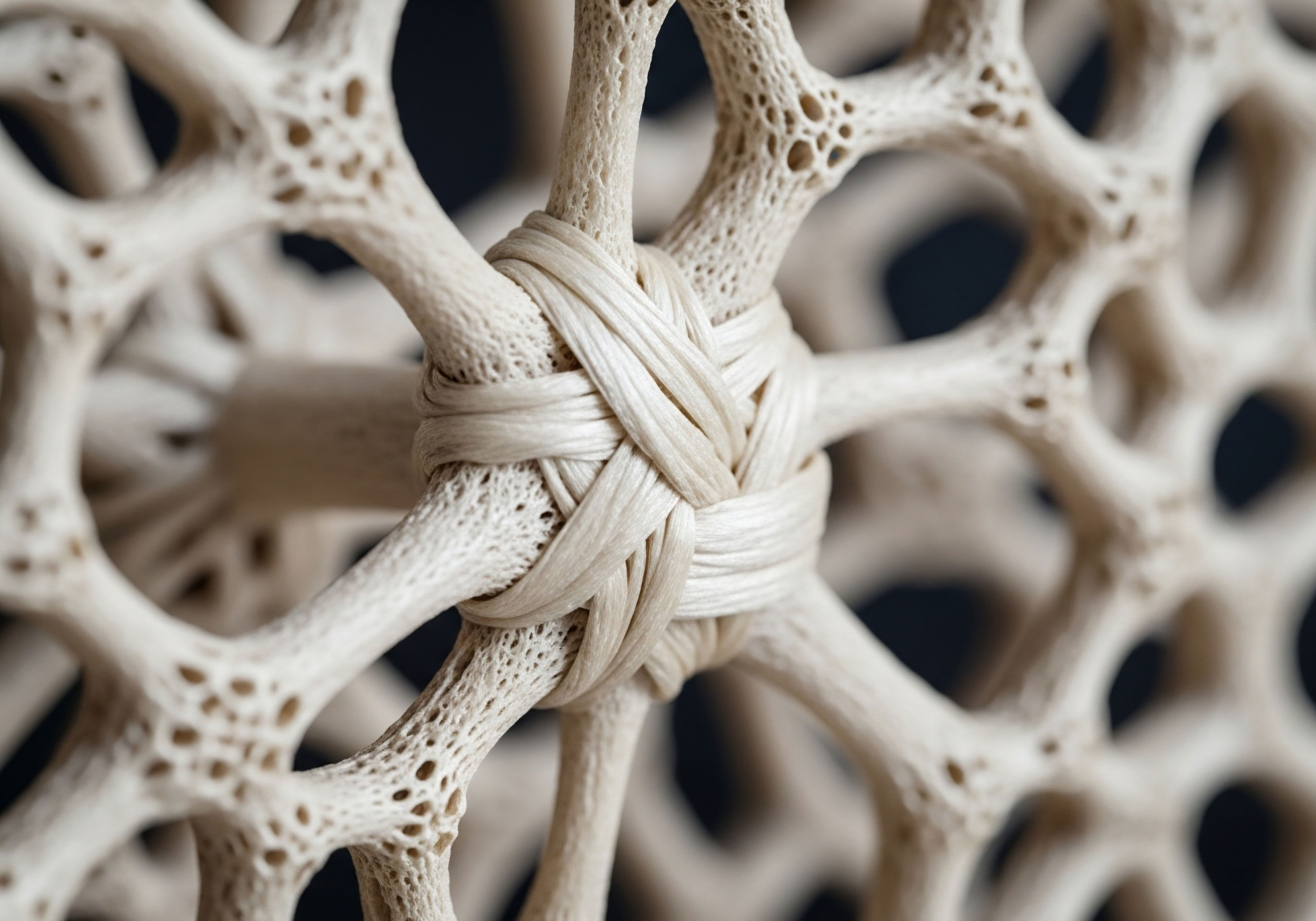

These moments are not figments of imagination; they are valid biological signals from a body undergoing profound systemic changes. One of the most significant of these changes involves the shifting architecture of your endocrine system, the body’s internal communication network. At the center of this conversation for many older adults, particularly women, is a molecule named progesterone.

Progesterone’s identity extends far beyond its well-known role in the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. It is a potent neurosteroid, a term that signifies its production within the brain and its active participation in the health and function of the central nervous system.

Its presence is integral to the maintenance of neurons, the specialized cells that transmit nerve impulses. When we discuss progesterone in a therapeutic context for brain health, the conversation must immediately address a point of frequent and critical confusion ∞ the distinction between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins.

Bioidentical progesterone possesses a molecular structure identical to the hormone your body produces. Synthetic progestins, while capable of performing some similar functions in the uterus, are different molecules with different downstream effects, particularly within the brain. This distinction is foundational to understanding its safety and efficacy for cognitive wellness.

Progesterone acts directly within the brain as a neurosteroid, influencing neuronal health and cognitive processes in ways that are distinct from its reproductive functions.

The Journey from Progesterone to Allopregnanolone

The story of progesterone’s influence on the brain becomes even more compelling when we follow its metabolic pathway. Inside the brain, progesterone is converted into other powerful molecules. The most significant of these is allopregnanolone (often abbreviated as ALLO). Think of allopregnanolone as one of progesterone’s most active and influential delegates within the nervous system.

Its primary role is to interact with and modulate the activity of GABA-A receptors. GABA, or gamma-aminobutyric acid, is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in your brain. It is the system responsible for producing feelings of calm, reducing neuronal excitability, and facilitating restful sleep. Allopregnanolone enhances the effect of GABA, acting as a master regulator of the brain’s internal equilibrium.

As individuals age, the natural production of progesterone declines significantly, especially in women following menopause. This leads to a concurrent drop in the brain’s supply of allopregnanolone. The reduction of this key neurosteroid can manifest in symptoms that feel very familiar to many older adults ∞ increased anxiety, disrupted sleep patterns, and a general sense of being unable to achieve a state of mental calm.

Understanding this biochemical chain of events allows us to reframe these symptoms. They are not simply abstract feelings; they are the physiological consequences of a measurable decline in a specific, powerful neurochemical system. Therefore, the therapeutic goal of using bioidentical progesterone is to replenish this system, restoring the brain’s access to the calming and protective influence of allopregnanolone.

What Are the Implications for Brain Structure and Function?

The decline in progesterone and its metabolites has implications that extend to the physical structure and resilience of the brain. Progesterone has been shown in numerous preclinical studies to have protective qualities. It supports the integrity of the myelin sheath, the fatty coating that insulates nerve fibers and ensures the rapid transmission of electrical signals.

It also exhibits anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, helping to shield brain cells from the types of metabolic stress and damage that accumulate over a lifetime. When considering the aging brain, which is more vulnerable to inflammatory processes and oxidative damage, the presence of adequate progesterone becomes an element of cellular defense.

This is why the conversation about hormonal therapy in older adults requires a systems-based perspective. The goal is the restoration of a biological environment in which the brain can optimally function and protect itself. It involves supplying the necessary molecular tools, like bioidentical progesterone, that the body uses to maintain its own complex systems.

The focus shifts from merely managing symptoms to addressing the underlying biochemical deficits that give rise to those symptoms in the first place, fostering an internal environment that supports cognitive vitality and neurological resilience.

Intermediate

Advancing our understanding of progesterone’s role in the brain requires a more detailed examination of its mechanisms of action and a direct comparison with its synthetic counterparts. The safety and efficacy of any hormonal protocol are determined by how precisely a therapeutic agent replicates the intended biological function without creating unintended consequences. This is where the molecular difference between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins becomes paramount, particularly concerning brain health in older adults.

Bioidentical progesterone, often delivered in a micronized form for better absorption, is chemically indistinguishable from the progesterone produced by the human body. This identical structure allows it to be recognized not only by progesterone receptors but also by the enzymes that convert it into its neuroactive metabolites, like allopregnanolone.

Synthetic progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), were designed to be structurally different. This was done to increase their patentability and potency, primarily for their effects on the uterine lining. These structural alterations mean they interact differently with receptors and are not metabolized into allopregnanolone. In fact, some progestins can interfere with the brain’s own production and function of its natural neurosteroids, leading to a completely different, and sometimes opposing, set of effects on mood and cognition.

The GABAergic System a Deeper Look

The primary mechanism through which progesterone, via allopregnanolone, exerts its calming and neuroprotective effects is its interaction with the GABA-A receptor. This receptor is a complex protein channel that, when activated by GABA, allows chloride ions to flow into a neuron.

This influx of negative ions makes the neuron less likely to fire an electrical impulse, effectively “quieting” the circuit. Allopregnanolone is a potent positive allosteric modulator of this receptor. This means it binds to a separate site on the receptor, enhancing its response to GABA. The result is a more profound and sustained inhibitory effect, which translates to reduced anxiety, easier sleep onset, and greater emotional stability.

Synthetic progestins do not provide this benefit. Lacking the ability to be converted into allopregnanolone, they fail to engage this powerful calming pathway. Some studies suggest that certain progestins may even have an excitatory effect in the brain or compete with the beneficial actions of estrogen, contributing to the negative mood symptoms and cognitive concerns reported by some women using specific formulations of hormone therapy.

This mechanistic difference explains why a woman using bioidentical progesterone might report feeling calmer and sleeping better, while another using a synthetic progestin might not experience these benefits, or could even feel worse.

The distinct molecular structures of bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins dictate their fundamentally different metabolic pathways and impacts on brain neurochemistry.

The following table illustrates the key distinctions between micronized progesterone and a common synthetic progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), especially in the context of brain health.

| Feature | Micronized Progesterone (Bioidentical) | Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA – Synthetic Progestin) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure |

Identical to the progesterone produced by the human body. |

Chemically altered from the progesterone molecule. |

| Metabolism in the Brain |

Converted into allopregnanolone and other neurosteroids. |

Is not converted into allopregnanolone. |

| Interaction with GABA-A Receptor |

Strongly enhances GABAergic inhibition via allopregnanolone, promoting calm and sleep. |

Does not enhance GABAergic inhibition; may have neutral or even opposing effects. |

| Reported Cognitive Effects |

Studies suggest neutral to positive effects on cognitive function. |

Associated in some large-scale studies (like the WHIMS) with an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. |

| Clinical Application in Protocols |

Used in female hormone balance protocols to support sleep, mood, and provide endometrial protection in conjunction with estrogen. |

Primarily used for endometrial protection; its use has declined due to concerns about its risk profile. |

The Critical Window Hypothesis

Another layer of complexity in this discussion is the “critical window” or “timing” hypothesis. Some research suggests that the neuroprotective benefits of hormone therapy are most pronounced when initiated closer to the onset of menopause. The theory posits that the brain’s hormonal receptors and cellular machinery remain more responsive to hormonal signaling for a certain period after menopause begins.

If therapy is started many years later, the brain may have already undergone structural changes or a downregulation of these receptors, making it less responsive to the therapy and potentially altering the risk-benefit calculation. While much of this research has focused on estrogen, the principle likely extends to progesterone, as its protective mechanisms are also dependent on a responsive cellular environment. This concept underscores the importance of proactive and personalized hormonal assessment during the perimenopausal and early postmenopausal years.

- Early Initiation ∞ Starting therapy within the first 5-10 years of menopause may allow progesterone to better support existing neural pathways and protect against age-related decline.

- Late Initiation ∞ Beginning therapy later in life requires a more careful evaluation, as the brain’s responsiveness may be diminished, and the overall health status of the individual plays a larger role in determining safety.

- Personalized Assessment ∞ The decision is always individual, based on a comprehensive evaluation of symptoms, biomarkers, and personal and family medical history, as recommended by organizations like The Endocrine Society.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of progesterone’s role in the aging brain necessitates a departure from generalized discussions of hormone therapy and a focused inquiry into the specific molecular pathways it modulates. The central thesis is that the neurobiological safety and utility of progesterone therapy in older adults are contingent almost entirely on the molecular form of the progestogen used and its subsequent metabolic conversion into neuroactive steroids, principally allopregnanolone.

The failure of large-scale clinical trials, such as the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), to show a cognitive benefit from hormone therapy can be largely attributed to their use of a synthetic progestin, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), which does not share the neurotrophic profile of endogenous progesterone.

Preclinical evidence provides a robust foundation for progesterone’s neuroprotective capabilities. In various animal models of neurological insult, including traumatic brain injury and ischemic stroke, the administration of progesterone has been shown to reduce cerebral edema, limit neuronal cell death, and improve functional outcomes.

These effects are mediated through a multitude of mechanisms ∞ progesterone upregulates the expression of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a key protein for neuronal survival and plasticity; it attenuates inflammatory cascades by reducing the activation of microglia and astrocytes; and it mitigates oxidative stress by enhancing the brain’s endogenous antioxidant systems. These protective actions are fundamental to maintaining neuronal integrity in the face of age-related stressors.

Allopregnanolone the Master Regulator of Neurogenesis and Brain Plasticity?

The most profound effects of progesterone on brain health are arguably mediated by its metabolite, allopregnanolone (ALLO). Research in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease has shown that ALLO levels are significantly reduced in the brain, and that restoring these levels can have remarkable therapeutic effects.

Studies have demonstrated that intermittent administration of allopregnanolone can promote neurogenesis ∞ the creation of new neurons ∞ in the hippocampus, a brain region critical for learning and memory. This regenerative effect was correlated with improved performance in cognitive tasks in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s. ALLO appears to stimulate neural stem cells to proliferate and differentiate, offering a mechanism not just for neuroprotection, but for actual neural repair and regeneration.

However, the dosing regimen of allopregnanolone is critical. Continuous, high-level exposure has, in some studies, shown paradoxical effects, potentially worsening amyloid pathology and impairing cognitive function. This suggests that the brain’s regenerative systems may require pulsatile or intermittent stimulation, mimicking natural hormonal fluctuations, rather than constant saturation.

This finding has significant implications for designing therapeutic protocols, favoring regimens that work in concert with the brain’s endogenous biological rhythms. The goal is to periodically activate these regenerative pathways, a process that is more akin to systems engineering than simple hormone replacement.

The neuroregenerative potential of progesterone therapy is mediated by its metabolite allopregnanolone, whose efficacy is critically dependent on an intermittent dosing strategy that stimulates endogenous repair mechanisms.

Reinterpreting Clinical Trial Data

With this mechanistic understanding, we can re-evaluate the data from major clinical trials. The WHIMS, a sub-study of the WHI, reported that a combination of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) and MPA was associated with an increased risk of dementia in women over 65.

This outcome has been widely interpreted as a condemnation of all hormone therapy for cognitive health. A more precise interpretation, however, points to the specific pharmacology of MPA. As established, MPA is not progesterone. It does not convert to ALLO and lacks its neurotrophic benefits.

Furthermore, some evidence suggests MPA may interfere with the neuroprotective actions of estrogen and may even possess some neurotoxic properties. Therefore, the WHIMS results are a powerful statement on the potential risks of MPA in the aging brain, but they provide little to no information about the safety or efficacy of bioidentical progesterone.

The following table summarizes key findings and provides a critical reinterpretation based on the progestogen used.

| Study / Finding | Common Interpretation | Clinically-Informed Reinterpretation |

|---|---|---|

| WHIMS Trial |

Hormone therapy increases dementia risk in older women. |

A specific formulation using conjugated equine estrogens and the synthetic progestin MPA increased dementia risk, highlighting the potential harms of MPA on the aging brain. This finding cannot be extrapolated to regimens using bioidentical hormones. |

| Preclinical Animal Models |

Progesterone shows promise in lab settings but is unproven in humans. |

Progesterone demonstrates robust neuroprotective and neuroregenerative mechanisms, primarily through its metabolite ALLO. These findings provide a strong biological rationale for testing bioidentical progesterone for cognitive health in human trials. |

| KEEPS Trial |

Early-initiated hormone therapy appears safer but has no significant cognitive effect. |

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study used oral micronized progesterone. It showed no harm to cognition and had a better overall safety profile than the WHI. The lack of a strong positive signal may relate to the study’s duration or population, but it supports the safety of bioidentical progesterone for the brain compared to MPA. |

In conclusion, a rigorous, evidence-based assessment indicates that the question of progesterone’s safety for brain health in older adults is fundamentally a question of molecular identity. The available data, from mechanistic cell studies to large-scale human trials, points toward a favorable safety profile for bioidentical micronized progesterone.

Its ability to be converted into the powerful neurosteroid allopregnanolone provides a clear biological mechanism for its potential to support neuronal health, promote calm and restorative sleep, and possibly even stimulate regenerative processes within the aging brain. Conversely, synthetic progestins like MPA lack these benefits and have been associated with adverse neurological outcomes.

The future of hormonal optimization for cognitive longevity depends on this precise, systems-level understanding, moving beyond generalized labels to focus on the specific biochemical actions of the molecules we use.

References

- Stute, P. Wildt, L. & Neulen, J. (2018). The impact of micronized progesterone on the endometrium ∞ a systematic review. Climacteric, 21(4), 308-316.

- Brunton, P. J. (2009). The role of neuroactive steroids in the regulation of mood and anxiety. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 21(4), 332-336.

- Brinton, R. D. (2013). Allopregnanolone as a regenerative therapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease ∞ translational development and clinical promise. Progress in Neurobiology, 105, 1-16.

- Singh, M. & Su, C. (2013). Progesterone and its metabolites ∞ neuroprotective effects and clinical implications. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70(11), 1937-1946.

- Schumacher, M. Mattern, C. Ghoumari, A. Oudinet, J. P. Liere, P. Labombarda, F. & Guennoun, R. (2014). Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system ∞ resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Progress in Neurobiology, 113, 6-39.

- de Lignières, B. & Vincens, M. (1982). Differential effects of exogenous oestradiol and progesterone on mood in post-menopausal women ∞ a placebo-controlled study. Maturitas, 4(1), 67-72.

- The Endocrine Society. (2015). Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(11), 3975-4011.

- Wang, J. M. Singh, C. Liu, L. Irwin, R. W. Chen, S. Chung, E. J. & Brinton, R. D. (2010). Allopregnanolone reverses neurogenic and cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(14), 6498-6503.

- Jiang, C. Wang, J. Li, X. Li, Y. & Zhang, L. (2016). Progesterone exerts neuroprotective effects and improves long-term neurologic outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage in middle-aged mice. Neurobiology of Aging, 42, 56-65.

- Wren, B. G. McFarland, K. & Edwards, D. (1999). Micronised progesterone and endometrial response. The Lancet, 354(9188), 1445-1446.

Reflection

The information presented here offers a detailed map of a specific territory within your own biology. It connects the subtle feelings of cognitive change to the complex, silent work of molecules like progesterone and allopregnanolone within your nervous system. This knowledge serves a distinct purpose ∞ to transform abstract concerns into a concrete understanding of the systems at play. It provides a new vocabulary and a more precise framework for observing your own health.

Consider the intricate network of your neuro-hormonal system. It is a dynamic environment, constantly adapting to internal and external signals. The introduction of any therapeutic agent is a significant new input into that system. The journey toward personalized wellness is one of informed decision-making, where you become an active participant in the dialogue about your own body.

This understanding is the first, essential step. The path forward involves using this knowledge not as a final answer, but as a powerful tool to ask better questions and to engage in a more meaningful partnership with a clinical expert who can help translate this systemic knowledge into a protocol tailored to your unique physiology.