Fundamentals

You begin a personal health protocol, a commitment to understanding and recalibrating your own biological systems. You track every variable ∞ your sleep latency, your heart rate variability, the precise timing of your hormonal therapy, your subjective sense of well-being.

This data, entered into the clean interface of a wellness application on your phone, feels like a private dialogue between you and your body. It is the very language of your progress, a stream of information that maps your journey back to vitality. The assumption is that this conversation is protected, shielded by a powerful regulation you have heard of ∞ HIPAA. This belief, while common, represents a critical vulnerability in your personal security architecture.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) functions with the specificity of a key fitting a single lock. It establishes a federal standard for the protection of patient information, yet its authority is precisely defined and narrowly applied.

The law governs how specific organizations, known as “covered entities” and their “business associates,” handle what is termed “protected health information” (PHI). Your direct relationship with a wellness app developer, in most scenarios, exists outside of this protected circle. The data you generate on a personal device, from fitness trackers to symptom logs, is generally not covered by HIPAA’s privacy and security rules.

Understanding the Boundaries of Protection

The protective power of HIPAA activates only within a specific clinical context. The information shared between you and your physician, your health insurance plan, or a healthcare clearinghouse constitutes PHI. An app developer becomes a “business associate” subject to HIPAA only when it creates, receives, maintains, or transmits PHI on behalf of a covered entity.

For instance, an application developed by your hospital to access your patient portal falls under HIPAA’s jurisdiction. A popular, commercially available wellness app that you download and use independently does not. This distinction is absolute.

Once you direct your health information to be sent from a covered entity to a third-party app, that data often loses its HIPAA-protected status upon arrival.

This transfer creates a legal handoff. The moment your data, at your request, flows from your doctor’s HIPAA-compliant electronic health record system to your personal wellness app, it crosses a regulatory boundary. The app developer, as a non-covered entity, is not bound by HIPAA’s rules for any subsequent use or disclosure of that information.

The protections you assumed were inherent to the data itself were, in reality, tied to the entity that held it. This reality exposes a significant gap between public perception and regulatory fact, a gap where the security of your most personal biological data resides.

What Constitutes a Covered Entity?

To clarify the operational limits of HIPAA, it is essential to identify the specific parties it governs. The regulation is built around a triad of specific organizational types.

- Health Plans ∞ This category includes health insurance companies, HMOs, company health plans, and certain government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

- Health Care Clearinghouses ∞ These are entities that process nonstandard health information they receive from another entity into a standard format, or vice versa. They function as intermediaries.

- Health Care Providers ∞ This encompasses doctors, clinics, psychologists, dentists, chiropractors, nursing homes, and pharmacies, but only if they transmit any information electronically in connection with a transaction for which HHS has adopted a standard.

Any organization falling outside these precise definitions, including the vast majority of wellness and fitness app developers, is not a HIPAA-covered entity. Their handling of your data is governed by a different set of rules and, critically, by the terms of their own privacy policies and user agreements.

Intermediate

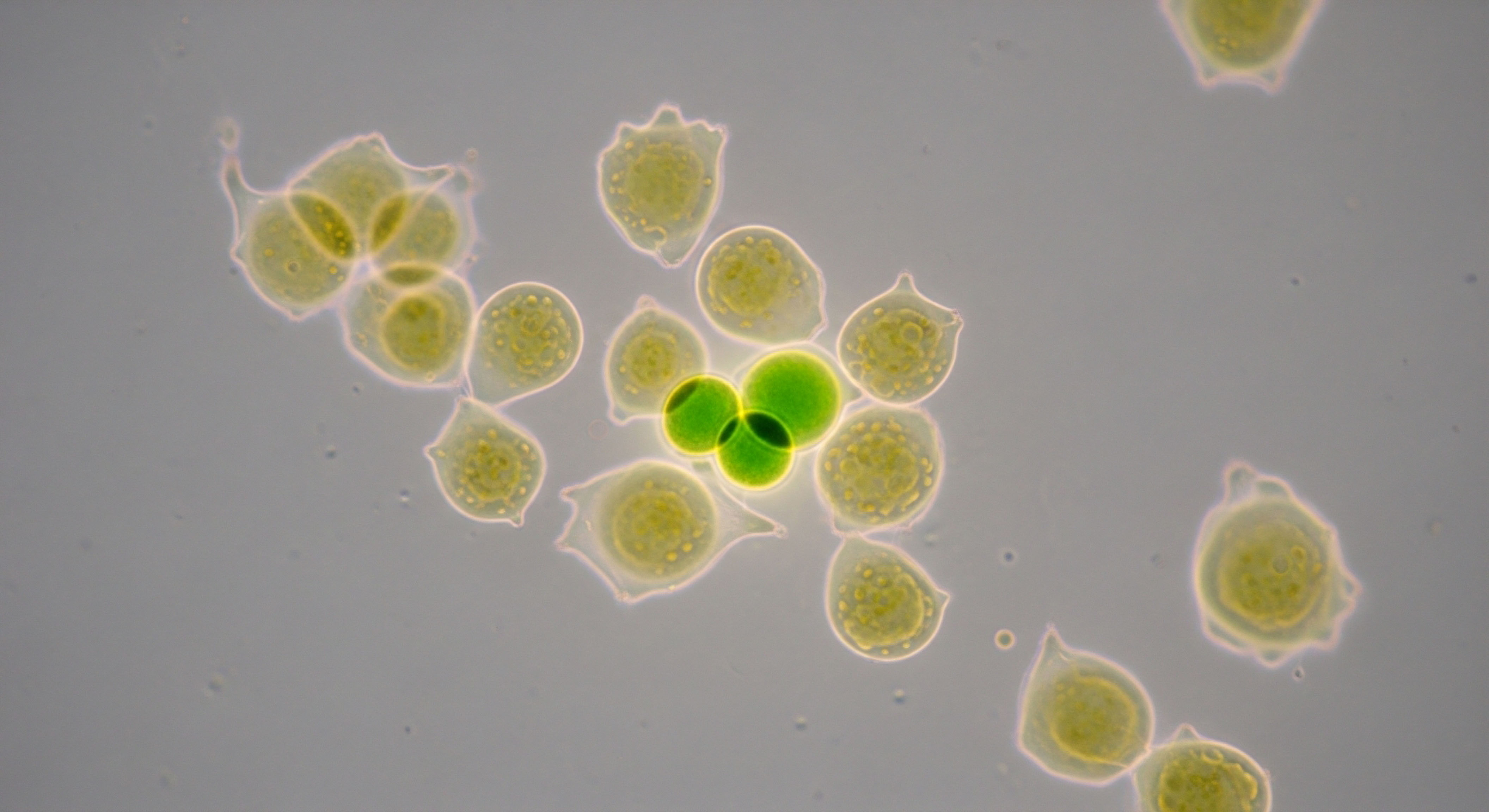

Recognizing that HIPAA’s shield does not extend to your personal wellness app is the first step. The next is to understand the landscape of actual risks and the alternative regulations that govern it. The data you are generating ∞ tracking your testosterone cypionate injections, noting changes in mood while on a Sermorelin protocol, or logging sleep quality improvements from Ipamorelin ∞ is of immense personal and commercial value.

Its security depends on the app’s internal architecture and the developer’s commitment to data integrity, a far more variable standard than HIPAA compliance.

The primary threats to your data within a non-HIPAA environment are threefold ∞ insufficient technical safeguards, opaque data sharing practices with third parties, and insecure data storage on your own device. Many applications transmit user data across unencrypted communication protocols, making it vulnerable to interception.

The code of the app itself may contain third-party software development kits (SDKs) designed to collect and share your personal information with advertisers or data brokers, often without transparent disclosure. This ecosystem of data exchange operates behind the user interface, transforming your personal health log into a marketable asset.

What Is the Real Regulatory Framework?

While HIPAA may not apply, your data is not entirely without protection. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) serves as the nation’s primary consumer protection agency. Through Section 5 of the FTC Act, it prohibits unfair or deceptive business practices, which includes misleading statements about data privacy.

More directly, the FTC enforces the Health Breach Notification Rule (HBNR). This rule mandates that vendors of personal health records and related entities not covered by HIPAA must notify their customers, the FTC, and sometimes the media in the event of a security breach involving unsecured health information.

The FTC’s definition of a “breach” is a critical point of distinction. Recent enforcement actions have clarified that a breach under the HBNR includes the unauthorized disclosure of user data to third parties, such as sharing sensitive health information with advertising platforms without the user’s explicit consent. This expands the concept of a breach beyond a malicious hack to include intentional, yet unauthorized, data sharing practices written into an app’s business model.

The FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule holds wellness apps accountable for unauthorized data sharing, treating it as a reportable security breach.

This regulatory posture provides a necessary layer of accountability. It forces app developers to be transparent about their data sharing relationships and to secure affirmative consent from users before their information is used for purposes like targeted advertising. The table below outlines the core differences in these two regulatory systems.

| Regulatory Aspect | HIPAA | FTC Health Breach Notification Rule (HBNR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | Governs Protected Health Information (PHI) held by covered entities (providers, plans) and their business associates. | Governs personal health records held by vendors and entities not covered by HIPAA, such as many health and wellness apps. |

| Focus | Establishes comprehensive privacy and security rules for the handling and use of PHI. | Primarily a breach notification rule, requiring disclosure after an incident. It defines “breach” broadly to include unauthorized sharing. |

| Enforcement Body | Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office for Civil Rights. | Federal Trade Commission (FTC). |

| Key Requirement for Data Use | Strict limits on use and disclosure of PHI without patient authorization. | Prohibits deceptive practices; requires notification for breaches, including unauthorized disclosures to third parties like advertisers. |

How Can You Mitigate Your Personal Risk?

Your personal vigilance is a key component of your data security. Understanding that the legal protections are different from what you may have assumed allows you to adopt a more proactive stance in safeguarding your information.

- Scrutinize Privacy Policies ∞ Read the privacy policy before downloading an app. Look for clear, unambiguous language about what data is collected, how it is used, and with whom it is shared. Vague statements are a signal of potential risk.

- Manage App Permissions ∞ When you install an app, it will request permissions to access various parts of your phone (e.g. location, contacts, microphone). Grant only the permissions that are essential for the app’s core function.

- Utilize Strong Authentication ∞ Use a strong, unique password for your wellness app. If the app offers multi-factor authentication (MFA), enable it. This provides a critical layer of security against unauthorized access to your account.

- Limit Data Input ∞ Consider the sensitivity of the information you are recording. Be mindful of entering uniquely identifying details alongside your health metrics. The more data points an app has, the more detailed a profile it can build.

Academic

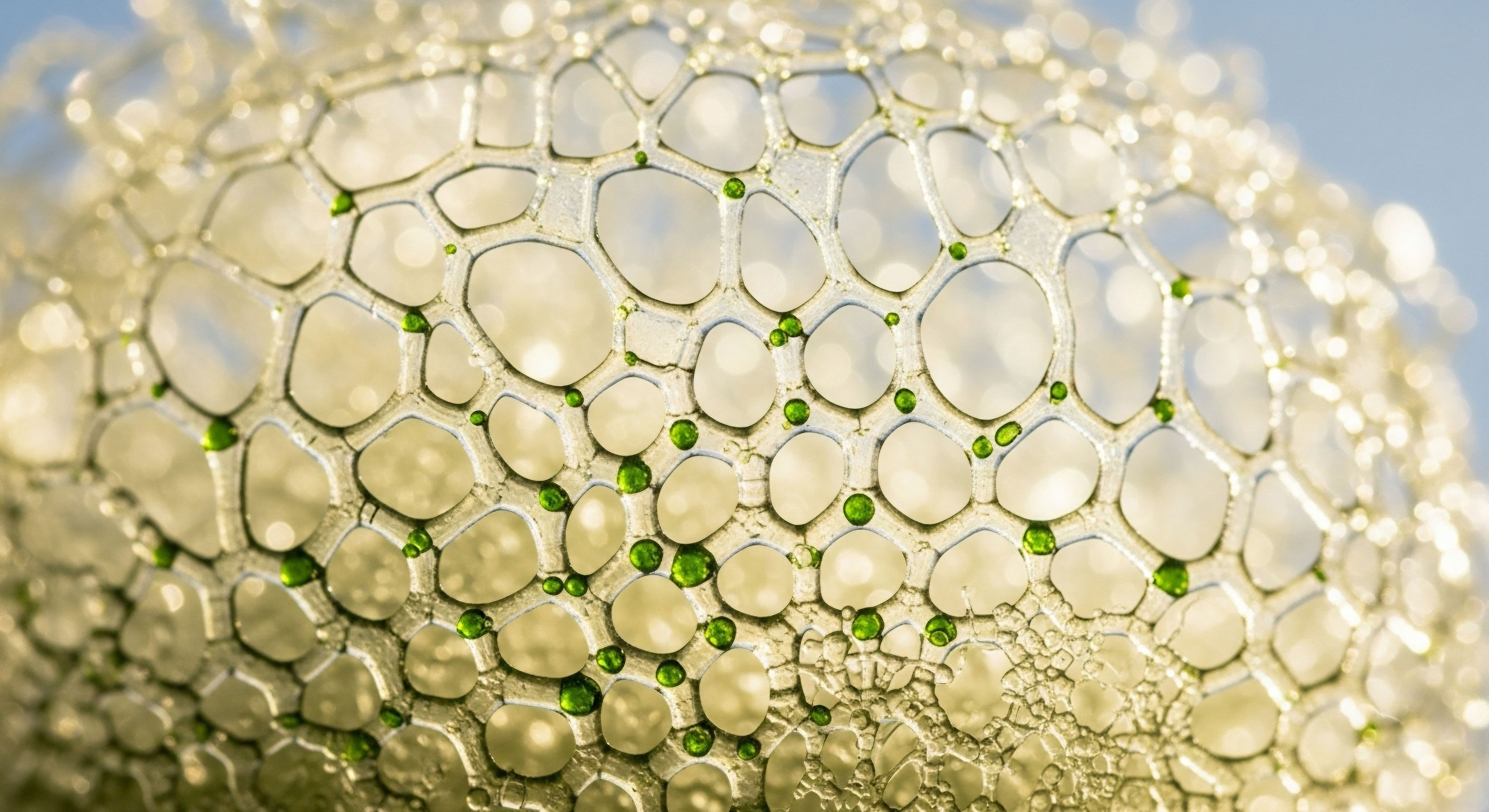

The conversation about data security in wellness applications transcends the legalistic boundaries of HIPAA and the FTC’s notification requirements. The most profound and technically sophisticated risk lies in the erosion of anonymity itself. The process of “de-identification,” whereby explicit identifiers like your name and address are removed from a dataset, is often presented as a solution for protecting privacy.

This process, however, is fundamentally fragile. The residual data, even when scrubbed of direct identifiers, retains a pattern, a signature of your biological and behavioral life that can be used to find you.

This vulnerability is exploited through the process of data re-identification. It occurs when a de-identified dataset is algorithmically cross-referenced with other available data sources. Public records, social media profiles, consumer marketing data, and information from other data breaches can be combined to triangulate and re-identify an individual within a supposedly anonymous health dataset.

Research has demonstrated that with just a few demographic data points, such as ZIP code, birth date, and gender, a high percentage of individuals can be uniquely identified within large populations. The addition of high-frequency data from a wellness app ∞ such as daily activity patterns, sleep cycles, or even heart rate ∞ makes this re-identification process substantially more reliable for a determined adversary.

What Is the Mechanism of Re-Identification?

Re-identification is an exercise in pattern matching at a massive scale. An “anonymized” dataset from a wellness app might contain your age range, your city, and a timestamped log of your heart rate. A data broker, a largely unregulated entity that buys and sells consumer information, may possess a separate dataset containing your exact name, address, and purchasing habits.

By linking these two datasets on a common attribute, such as location and demographic data, the broker can collapse the anonymity and connect your name to your specific health information. This is not a theoretical exercise; it is a core component of the data economy.

| Data Type Collected by Wellness App | Potential for Re-Identification and Misuse |

|---|---|

| Geolocation Data | Can reveal home and work addresses, daily routines, and visits to clinical facilities, which can be linked to other public or purchased datasets. |

| Biometric Data (Heart Rate, Sleep) | Unique physiological patterns can serve as a “biometric signature” for re-identification when combined with other demographic information. |

| Hormonal Protocol Logs | Disclosure could lead to discrimination in insurance or employment, or targeted marketing for related products. |

| Symptom and Mood Journals | Highly sensitive subjective data that provides deep insights into psychological and physiological states, valuable for marketing and profiling. |

The Ethics of the Data Economy

This leads to the central ethical dilemma of the digital wellness space ∞ the monetization of your health data. When you use a “free” wellness app, the service is often paid for by the data you generate.

Your information becomes a commodity, sold or licensed to third parties for a variety of purposes, including pharmaceutical research, insurance underwriting, and direct-to-consumer advertising. While some of these uses may contribute to a public good, the process often lacks transparency and informed consent.

The re-identification of de-identified health data transforms a tool for personal wellness into a source of commercially valuable, and deeply personal, intelligence.

The consent you provide in a lengthy, legalistic user agreement may not fully articulate that your data could be used to build a profile that assesses your health risks for an insurance company or targets you with ads based on a medical condition you are tracking.

This asymmetry of information and power challenges the very foundation of patient autonomy. The data that represents your personal journey toward health can be used in ways that are disconnected from, and potentially counter to, your own interests. The security of your wellness app, therefore, is a question of systemic ethics and the architecture of the modern data economy.

It reveals that true compliance requires a framework that protects data not just from overt theft, but from its intended, and often opaque, use as a commercial asset.

References

- Sampat, Brinda Hansraj, and Bala Prabhakar. “Privacy and Security concerns in using mHealth apps.” CSUSB ScholarWorks, 2017.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “The access right, health apps, & APIs.” HHS.gov, 30 May 2025.

- Korff, “Erosion of Anonymity ∞ Mitigating the Risk of Re-identification of De-identified Health Data.” American Health Law Association, 2019.

- Federal Trade Commission. “Complying with FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule.” FTC.gov.

- “Data Monetization in Healthcare ∞ A Strategic Approach.” Sigma Computing, 18 Nov. 2024.

- Gellman, Robert. “Big Data and Consumer Privacy in the Internet Economy.” World Privacy Forum, 2015.

- Tene, Omer, and Jules Polonetsky. “Big Data for All ∞ Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics.” Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property, vol. 11, 2013.

- “Risks & Rewards of Monetizing Healthcare Data.” The Parnassus Group, 7 Sept. 2022.

- Dickinson Wright PLLC. “App Users Beware ∞ Most Healthcare, Fitness Tracker, and Wellness Apps Are Not Covered by HIPAA.” 2021.

- Tangari, G. et al. “Security and Privacy in Mobile Health Applications ∞ A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 2021.

Reflection

You now possess a clearer map of the digital territory where your health journey is being recorded. You understand the specific, limited jurisdiction of HIPAA and the broader, different role of the FTC. You see the subtle mechanics of de-identification and the economic forces that drive the trade of personal data.

This knowledge is the foundational element of true digital sovereignty. It shifts your posture from one of passive trust to one of active, informed engagement. The security of your data is not a feature provided by a single law, but a state you cultivate through conscious choices.

As you continue your personal wellness protocols, consider the value of the information you create. It is more than a series of data points; it is the biological narrative of your life. The next step is to decide, with intention, how and with whom that story is shared.

Glossary

personal health

hipaa

protected health information

wellness app

your personal wellness

health information

personal wellness

third parties

data sharing

federal trade commission

consumer protection

health breach notification rule

ftc

de-identification

data re-identification