Fundamentals

The feeling is a familiar one for many. It often begins subtly, a gradual shift in your body’s internal landscape. Energy levels that once felt boundless now seem to have a much lower ceiling. Sleep may become less restorative, and a sense of vitality can feel just out of reach.

You are living in the same body, yet its operational parameters feel altered. This experience is a valid and deeply personal starting point for a journey into understanding your own biology. Your body communicates its needs through these feelings, signaling a change in its intricate internal systems.

At the heart of this communication network lies the endocrine system, a collection of glands that produce and secrete hormones. These chemical messengers travel throughout your bloodstream, acting as a sophisticated internal messaging service that regulates nearly every aspect of your physiology, from your metabolism and mood to your sleep cycles and stress responses.

When we discuss hormonal health, particularly in the context of aging and wellness, the conversation often turns to hormone replacement. This is where the distinction between “bioidentical” and “synthetic” hormones becomes a central point of consideration. The defining characteristic of a bioidentical hormone is its molecular structure.

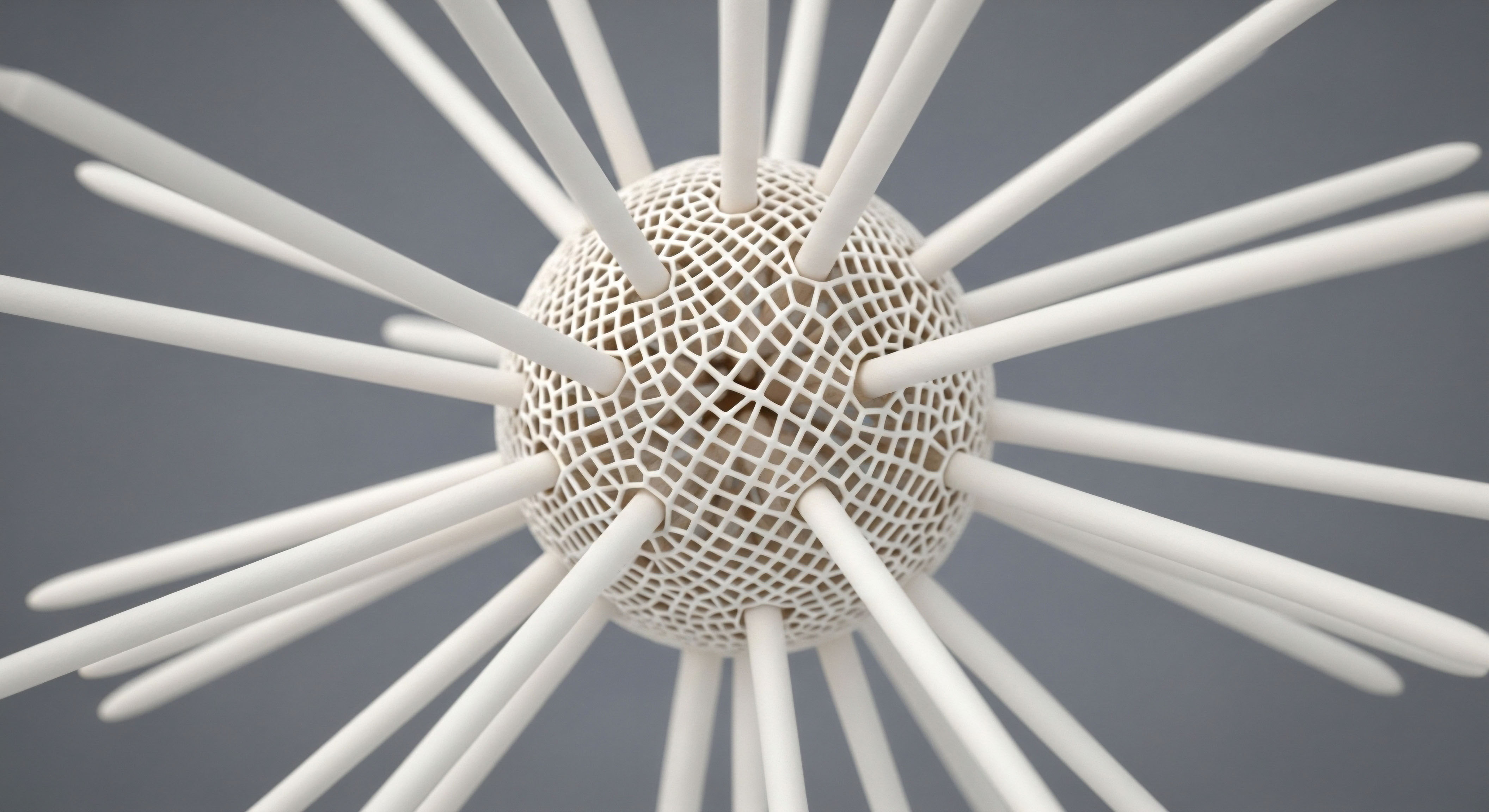

A bioidentical hormone, such as 17-beta estradiol, micronized progesterone, or testosterone, possesses a chemical architecture that is identical to the hormones produced naturally within the human body. Think of a specific lock and key. Your body’s hormone receptors are the locks, and the hormones it produces are the perfect keys, designed to fit precisely and initiate a specific, predictable biological action. Bioidentical hormones are, in essence, perfect duplicates of these original keys.

A bioidentical hormone is molecularly identical to the hormones your body produces, designed to fit its receptors perfectly.

Synthetic hormones, conversely, are molecules developed in a laboratory that are structurally different from human hormones. These compounds, such as conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs) or synthetic progestins like medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), are designed to interact with the same hormonal locks.

They are similar enough to the body’s natural keys that they can turn the lock and produce a hormonal effect. However, their structural differences mean they are an imperfect fit. This molecular variance is the origin of the entire discussion about safety and efficacy.

The way a hormone is structured dictates how it is recognized by the body, how it binds to receptors, what signals it sends to the cell, and how it is eventually broken down and eliminated. These differences in metabolism and cellular signaling are what lead to the distinct physiological effects observed between bioidentical and synthetic hormonal protocols in clinical practice.

Understanding the Source and Structure

The term “bioidentical” refers exclusively to the molecular shape of the hormone, not its source. Many bioidentical hormones are synthesized from plant-based compounds, such as diosgenin from wild yams or soy. The crucial step is the laboratory process that converts these plant precursors into molecules that are indistinguishable from human hormones.

Synthetic hormones, on the other hand, are intentionally designed with different molecular structures. For instance, CEEs, derived from the urine of pregnant mares, contain a mixture of estrogens that are natural for horses but foreign to human physiology. Synthetic progestins were created to have progesterone-like effects but with altered chemical bonds that change how they behave in the body.

This fundamental distinction in molecular identity is the foundation upon which all clinical comparisons of safety, efficacy, and long-term impact on health are built. Understanding this allows you to move the conversation from a general preference for “natural” substances to a precise, science-based inquiry into how molecular structure dictates biological function.

Intermediate

As we move from foundational concepts to clinical application, the conversation about bioidentical and synthetic hormones becomes a detailed examination of specific protocols and their physiological impacts. The choice between these molecules is grounded in their differing interactions with the human body, which has significant implications for both men and women seeking to optimize their endocrine function.

Clinicians who specialize in hormonal health design protocols based on an individual’s unique biochemistry, symptoms, and health goals. This personalization is a key element of modern endocrine system support, moving away from a one-size-fits-all model to a tailored biochemical recalibration.

Progesterone and Progestins a Critical Distinction

Perhaps the most significant area where the differences between bioidentical and synthetic hormones are apparent is in the use of progesterone versus synthetic progestins. In women’s health, progesterone is essential for regulating the menstrual cycle and maintaining pregnancy. For hormone therapy, its primary role is to protect the uterine lining from the proliferative effects of estrogen.

Bioidentical progesterone, specifically micronized progesterone, is structurally identical to the hormone produced by the ovaries. Clinical observations suggest that its effects extend beyond the uterus, positively influencing sleep, mood, and brain health. Many patients report a calming, anxiolytic effect from oral micronized progesterone, which is attributed to its metabolite, allopregnanolone, acting on GABA receptors in the brain.

Synthetic progestins, such as medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), were developed to provide the necessary uterine protection but possess a different molecular structure. This structural variance leads to a different profile of effects. Unlike bioidentical progesterone, many synthetic progestins do not produce the same calming metabolites.

Some patients experience negative mood effects, such as anxiety or depression, when using them. Furthermore, their molecular shape allows them to bind to other types of hormone receptors, including androgen and glucocorticoid receptors, which can lead to a range of unintended side effects.

The data from large-scale studies, including the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), indicated that the use of MPA in combination with CEE was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer compared to estrogen alone. Subsequent research suggests that bioidentical progesterone does not appear to confer this same level of risk and may have a more neutral or even protective effect on breast tissue.

The molecular difference between bioidentical progesterone and synthetic progestins results in distinct effects on mood, sleep, and breast health.

The following table provides a comparative overview of the clinical characteristics of bioidentical progesterone and a common synthetic progestin.

| Feature | Bioidentical Progesterone (Micronized) | Synthetic Progestin (e.g. Medroxyprogesterone Acetate) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Identical to human progesterone | Chemically altered structure |

| Effect on Mood | Often calming, may improve sleep due to metabolites | Can be associated with anxiety, depression, or irritability |

| Cardiovascular Impact | Appears to have a neutral or beneficial effect on blood lipids and vascular health | Some progestins may negatively affect blood lipid profiles |

| Breast Cancer Risk | Associated with a lower risk compared to synthetic progestins | Associated with an increased risk when combined with estrogen |

| Receptor Specificity | High specificity for progesterone receptors | May bind to androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptors |

How Do Clinicians Personalize Hormonal Protocols?

Personalized hormonal optimization begins with a comprehensive evaluation. This process involves detailed symptom analysis, a thorough personal and family medical history, and extensive laboratory testing. Blood tests provide a quantitative snapshot of an individual’s hormonal status, measuring levels of key hormones like testosterone, estradiol, progesterone, DHEA, and thyroid hormones, as well as important markers for metabolic health.

Based on this data, a clinician can design a protocol tailored to the patient’s specific needs. For example, a man experiencing symptoms of andropause with confirmed low testosterone would be a candidate for Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT).

A standard TRT protocol for men often involves weekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of Testosterone Cypionate, a bioidentical form of testosterone. To maintain the body’s own hormonal feedback loops and testicular function, adjunctive therapies are frequently included. Gonadorelin, a peptide that stimulates the pituitary gland, may be prescribed to support natural testosterone production and fertility.

Anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, is often used in small doses to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, thereby preventing side effects like water retention or gynecomastia. For women, testosterone therapy is also a valuable tool, particularly for addressing symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and mood changes. The protocols for women use much lower doses, typically administered via subcutaneous injection or as long-acting pellets, to restore testosterone to healthy physiological levels.

The following table outlines typical starting protocols for male and female hormone optimization, emphasizing that these are starting points that require ongoing adjustment based on patient response and follow-up lab work.

| Protocol Component | Male Patient Example (Andropause) | Female Patient Example (Perimenopause) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Hormone | Testosterone Cypionate (e.g. 200mg/ml) weekly | Testosterone Cypionate (e.g. 10-20 units) weekly |

| Uterine Protection | Not applicable | Micronized Progesterone (if uterus is present) |

| System Regulation | Gonadorelin (to support natural production) | Protocols are tailored to the menstrual cycle or menopausal status |

| Estrogen Management | Anastrozole (as needed to block excess conversion) | Estradiol (bioidentical) may be added for vasomotor symptoms |

| Monitoring | Regular blood work to monitor testosterone, estrogen, and blood cell counts | Regular blood work and symptom tracking to adjust dosages |

The goal of these protocols is to restore hormonal balance in a way that mimics the body’s natural physiology as closely as possible. This is why bioidentical hormones are often the preferred choice in these personalized models. They provide the necessary molecular keys to operate the body’s systems without the confounding variables introduced by structurally different synthetic compounds.

The process is dynamic, requiring a strong partnership between the patient and the clinician to fine-tune dosages and achieve optimal outcomes, leading to enhanced vitality and long-term well-being.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of hormonal therapy’s role in longevity requires a shift in perspective, moving from simple symptom management to a deep appreciation for molecular mimicry and its long-term consequences on cellular health.

The central question of whether bioidentical hormones offer a safer and more effective path to longevity than their synthetic counterparts can be addressed by examining their interactions within the body’s complex regulatory networks. The body does not merely react to the presence of a hormone; it engages in a detailed biochemical conversation with it.

The structure of the hormone molecule is the language of that conversation. When the language is native (bioidentical), the conversation is fluent and predictable. When it is a foreign dialect (synthetic), the message can be misinterpreted, leading to unintended biological consequences over time.

Molecular Mimicry and Its Consequences for Long Term Health

The concept of molecular mimicry is central to this discussion. Bioidentical hormones are exact replicas of endogenous hormones, allowing them to participate seamlessly in the body’s intricate signaling cascades and metabolic pathways. Synthetic hormones, by contrast, are molecular analogues designed to elicit a primary hormonal response but differing in structure.

This structural variance necessitates different metabolic pathways for their breakdown and elimination, potentially generating metabolites that are themselves biologically active in ways that are not fully understood. This distinction is critical for long-term health, as the chronic exposure to non-native molecules and their byproducts may contribute to cellular stress, inflammation, and other processes that underlie age-related decline.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis serves as a primary example of these delicate feedback systems. This network operates on a sensitive feedback loop where the end-product hormones (testosterone and estrogen) signal back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to downregulate their own production. Bioidentical hormones participate in this feedback loop in a physiological manner.

Some synthetic hormones, however, can provide a stronger, more suppressive, or qualitatively different signal, potentially disrupting the natural rhythm of the HPG axis more profoundly. Restoring hormonal balance with molecules that the body recognizes and can metabolize through established, clean pathways is a cornerstone of a longevity-focused approach. The objective is to support the existing biological system, not to override it with foreign compounds.

What Are the Unresolved Questions in Bioidentical Hormone Research?

While a significant body of evidence points toward a favorable safety profile for bioidentical hormones, particularly progesterone over synthetic progestins, the field is not without areas requiring further investigation. The majority of large-scale, long-term randomized controlled trials, like the WHI, were conducted using synthetic or non-human hormones.

Consequently, the data for bioidentical hormones is often derived from smaller observational studies, clinical experience, and extrapolation from our understanding of physiology. There is a clear need for more extensive, long-term comparative studies that directly assess the effects of bioidentical estradiol and micronized progesterone on cardiovascular outcomes, dementia risk, and cancer incidence over decades.

Additionally, the practice of custom-compounding bioidentical hormones, while allowing for personalized dosing, presents challenges for standardization and regulatory oversight, a point often raised by organizations like the FDA. Resolving these questions through rigorous research will provide a more definitive evidence base to guide clinical practice for decades to come.

Long-term, large-scale trials comparing bioidentical and synthetic hormones are needed to definitively clarify differences in longevity outcomes.

Receptor Binding and Downstream Cellular Signaling

The interaction between a hormone and its receptor is a highly specific event that initiates a cascade of intracellular signals, ultimately altering gene expression. The affinity and specificity of this binding are dictated by the hormone’s three-dimensional structure. Bioidentical hormones fit their target receptors with perfect precision, initiating the intended physiological response.

Synthetic hormones, with their altered structures, may bind to the same receptor but with different affinity or stability. This can alter the downstream signal. For example, some synthetic progestins have been shown to have a different effect on the proliferation of breast cancer cells in vitro compared to natural progesterone.

Moreover, the lack of specificity of some synthetic molecules is a significant concern. Medroxyprogesterone acetate and other testosterone-derived progestins can bind to androgen receptors, leading to androgenic side effects like acne or hair loss. They can also interact with glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors, affecting stress response pathways and fluid balance.

Bioidentical progesterone does not exhibit this same level of cross-reactivity. These off-target effects introduce a level of biological noise and potential disruption that is absent with bioidentical hormones. From a longevity perspective, the goal is to maintain the integrity of cellular communication. Using molecules that deliver a clean, specific signal without unintended cross-talk is a more logical strategy for supporting long-term cellular health and minimizing the risk of iatrogenic complications.

- Bioidentical Progesterone ∞ Binds specifically to the progesterone receptor. Its metabolite, allopregnanolone, positively modulates GABA-A receptors, promoting calming and pro-sleep effects. It appears to have a neutral or protective role in breast and cardiovascular tissue.

- Synthetic Progestins (e.g. MPA) ∞ Bind to progesterone receptors but also exhibit cross-reactivity with androgen, glucocorticoid, and mineralocorticoid receptors. This can lead to a wide array of off-target effects, including negative impacts on mood, metabolic markers, and an association with increased breast cancer risk in some studies.

- Bioidentical Estrogens (e.g. Estradiol) ∞ Bind to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) and are metabolized through predictable pathways. Transdermal administration avoids the first-pass metabolism in the liver, which is associated with a lower risk of blood clots compared to oral synthetic estrogens.

- Synthetic Estrogens (e.g. CEEs) ∞ Comprise a mix of equine estrogens that interact with human estrogen receptors but are metabolized into a complex array of compounds, some of which may have different biological activities. Oral formulations have been linked to an increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

Ultimately, the argument for bioidentical hormones in a longevity-focused clinical practice is rooted in a fundamental principle of biochemistry and physiology. By using molecules that are identical to those the body has evolved to use and metabolize over millennia, we are choosing a path of minimal biological disruption.

This approach seeks to restore the body’s intricate hormonal symphony with its own native instruments, rather than introducing new ones that may play a similar tune but with a different and potentially dissonant timbre. The accumulated evidence, particularly regarding the differences between progesterone and synthetic progestins, strongly suggests that molecular identity is a critical factor in the safety and physiological compatibility of hormone therapy.

References

- Holtorf, Kent. “The bioidentical hormone debate ∞ are bioidentical hormones (estradiol, estriol, and progesterone) safer or more efficacious than commonly used synthetic versions in hormone replacement therapy?.” Postgraduate medicine, vol. 121, no. 1, 2009, pp. 73-85.

- “A comprehensive review of the safety and efficacy of bioidentical hormones for the management of menopause and related health risks.” Alternative Medicine Review, vol. 11, no. 3, 2006, pp. 208-223.

- Asi, N. et al. “Progesterone vs. synthetic progestins and the risk of breast cancer ∞ a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Systematic Reviews, vol. 5, no. 1, 2016, p. 121.

- Staser, K. et al. “The FASEB Journal.” The FASEB Journal, vol. 27, no. 1_supplement, 2013, pp. lb335-lb335.

- “Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 11, 2015, pp. 3975-4011.

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism ∞ an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

- Lara Briden. “The Crucial Difference Between Progesterone and Progestins.” Lara Briden – The Period Revolutionary, 2024.

- “Joint Trust Guideline for the Adult Testosterone Replacement and Monitoring.” NHS, 2024.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here offers a map of the complex territory of hormonal health. It translates the language of the laboratory and the clinic into a framework for understanding your own body. This knowledge is the essential first step.

It empowers you to ask informed questions and to view your own health not as a series of disconnected symptoms, but as an integrated system. Your personal health story, with its unique patterns and feelings, is the context in which this scientific information becomes truly meaningful.

Consider the intricate systems at play within you. The path toward sustained vitality is a personal one, built on a deep understanding of your individual biochemistry. The ultimate goal is to move through life with your body’s systems working in concert, allowing you to function with clarity and strength. This journey of biological self-awareness is a proactive and profound investment in your future self.