Fundamentals

You may have found yourself in a doctor’s office, describing a constellation of symptoms ∞ fatigue that sleep does not touch, a subtle but persistent decline in vitality, a change in your body’s resilience ∞ only to be met with a limited set of solutions.

This experience, of feeling a profound shift within your own biology while the available answers seem narrow, is a common starting point in the journey of understanding hormonal health. The path to reclaiming your body’s optimal function begins with understanding the system that governs the very tools a clinician can offer. This system is the regulatory landscape, and its architecture directly shapes your personal health choices.

At the heart of this architecture is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA’s primary role is to act as a gatekeeper for public health, ensuring that medicines available on the mass market have demonstrated both safety and effectiveness for a specific purpose.

The process is meticulous, lengthy, and resource-intensive, designed to protect the population from ineffective or harmful products. It is a system built on large-scale data, demanding rigorous evidence from extensive clinical trials before a new drug can be approved for sale. This structured evaluation provides a crucial layer of confidence and standardization in medicine.

The Pathway to an Approved Hormone Therapy

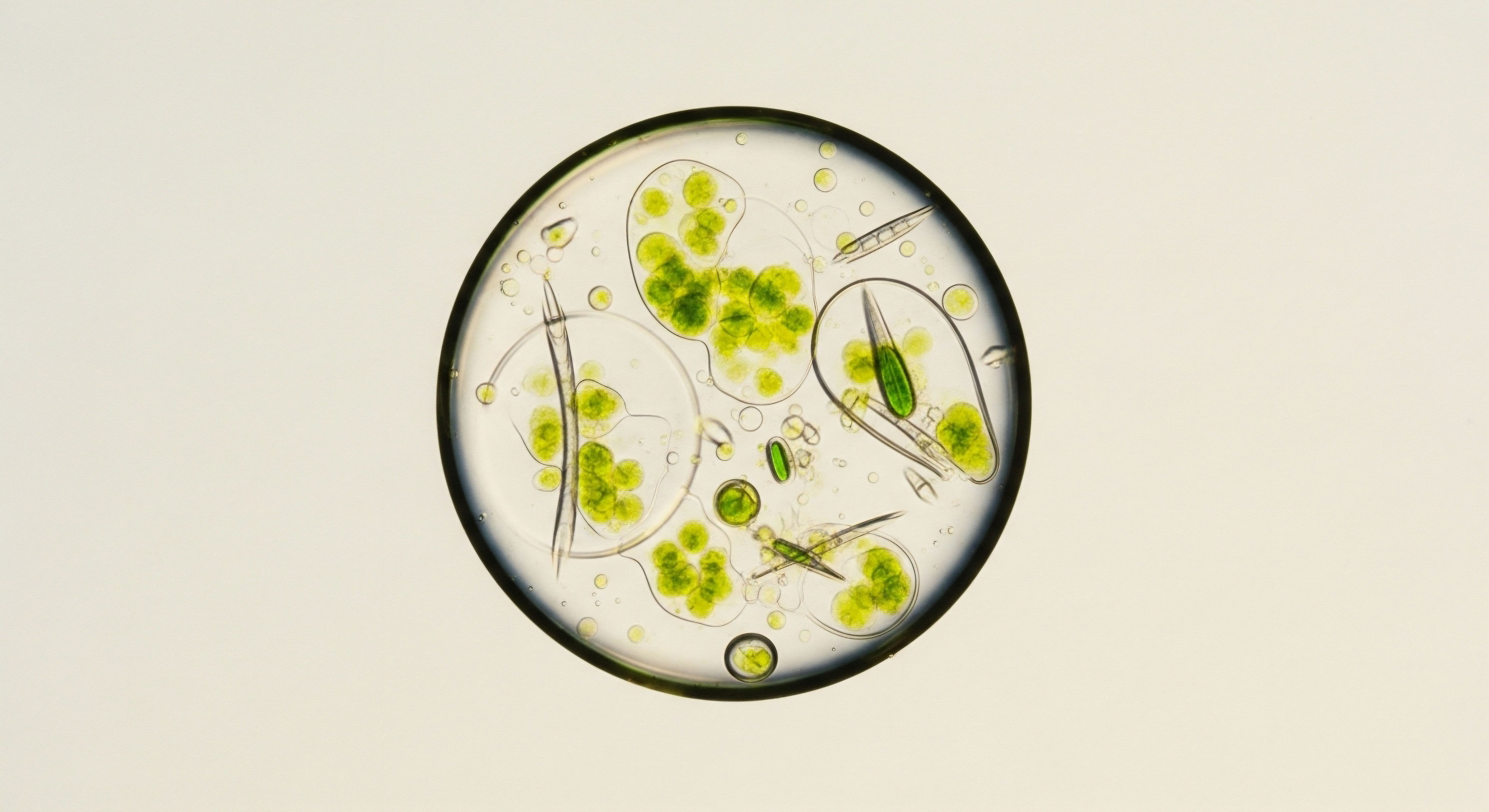

The journey of a new hormone therapy from a laboratory concept to a prescription you can fill is a multi-stage process grounded in scientific validation. This progression is designed to answer fundamental questions about how the substance works, its potential for harm, and its ultimate benefit in a living human system. Each phase represents a higher level of scrutiny and a greater investment of time and resources.

Initially, a potential drug undergoes preclinical testing in laboratory and animal models. This phase establishes basic biological activity and assesses for immediate safety concerns. If the results are promising, the drug’s sponsor submits an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA, detailing the plan for human trials. These clinical trials unfold in a sequence of three primary phases:

- Phase I trials involve a small number of healthy volunteers. The main goal here is to determine the drug’s pharmacokinetic properties ∞ how it is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted ∞ and to identify any acute safety issues.

- Phase II trials expand to a larger group of individuals who have the condition the drug is intended to treat. This stage provides preliminary data on the therapy’s effectiveness and further clarifies its safety profile and optimal dosage.

- Phase III trials are the most extensive and pivotal. These are large-scale, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that can involve hundreds or thousands of participants. The new drug is compared against a placebo or an existing standard treatment to definitively establish its efficacy and to build a comprehensive safety database.

Only after successfully completing this entire sequence can a pharmaceutical company submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA. A team of physicians, statisticians, pharmacologists, and other scientists then conducts an independent and unbiased review of all the submitted data. If they conclude that the drug’s documented health benefits outweigh its known risks for the intended population, it receives approval.

The FDA’s rigorous approval process is the mechanism that validates a drug’s safety and effectiveness for a specific medical condition.

What Does Commercial Interest Mean in This Context?

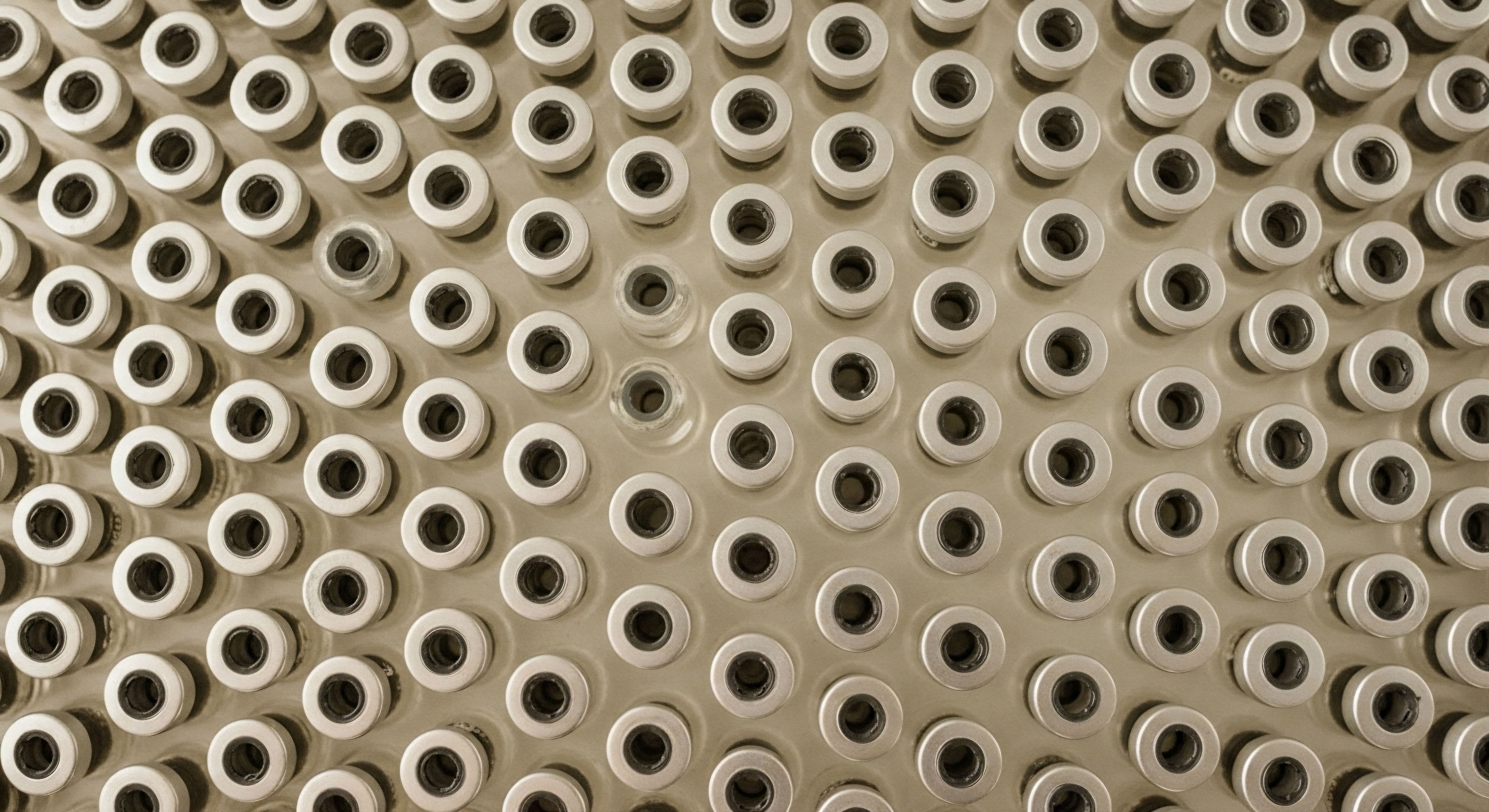

The immense cost and time associated with this approval process, often spanning a decade and costing hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars, introduces a powerful commercial element into hormone product development. A pharmaceutical company undertakes this massive financial risk with the expectation of a return on its investment.

This financial reality creates a commercial bias, a force that influences which potential therapies are pursued and which are left unexplored. The system inherently favors the development of novel, patentable molecules. A patent grants the company exclusive rights to market the drug for a period, allowing it to recoup its research and development costs and generate profit.

This commercial imperative means that substances that cannot be patented, such as bioidentical hormones which are molecularly identical to those produced by the human body, receive significantly less attention and funding for large-scale clinical trials. Testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone themselves are naturally occurring molecules and cannot be patented.

While specific delivery systems or synthetic variations can be, the underlying hormones themselves are off-limits for this kind of commercial protection. Consequently, the financial incentive to run a massive Phase III trial for a new application of a bioidentical hormone is substantially lower than for a new synthetic analogue.

This economic reality shapes the landscape of available treatments and is a primary reason why the conversation around hormonal health can feel divided between standardized, FDA-approved synthetic options and more individualized, bioidentical protocols.

Intermediate

Understanding the foundational FDA approval process allows us to examine how regulatory policy specifically interacts with the world of hormone therapies. The policies are not abstract rules; they are the direct cause behind why certain hormonal protocols, like those for menopausal symptom relief, have a clear evidence base, while others, such as testosterone therapy for women or advanced peptide therapies, exist in a more clinically nuanced space.

The regulatory framework creates distinct categories of hormonal products, each with its own level of evidence, accessibility, and risk profile.

The FDA provides specific guidance for companies developing hormone therapies (HT) for common indications like the vasomotor symptoms of menopause (hot flashes and night sweats). For a product combining estrogen and a progestogen, the agency requires a 12-month, double-blind, randomized controlled trial to assess not only its effectiveness in reducing symptoms but also its impact on endometrial safety.

This level of specific instruction streamlines the development process for therapies targeting this large market, which in turn encourages commercial investment. The result is a selection of well-studied, FDA-approved products for this specific application.

How Does Policy Differentiate Hormone Products?

Regulatory policy creates a clear line between FDA-approved manufactured drugs and compounded medications. This distinction is perhaps the most significant factor influencing the choices available to you and your clinician. It is a distinction rooted in the difference between mass production and individual preparation.

| Feature | FDA-Approved Hormone Products | Compounded Hormone Preparations |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing & Oversight | Produced in large batches at FDA-inspected facilities under strict Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). Every batch is tested for purity, potency, and consistency. | Prepared individually by a pharmacist in a compounding pharmacy for a specific patient based on a prescription. Oversight is primarily by state boards of pharmacy. |

| Evidence of Efficacy | Proven effective for a specific indication through extensive Phase III clinical trials involving hundreds or thousands of participants. | Efficacy is not established through large-scale trials. It is based on the known physiological action of the active ingredients and the clinical judgment of the prescriber. |

| Safety Data | A comprehensive safety profile is established during clinical trials and monitored through post-market surveillance. Known risks are listed in a detailed product insert. | Lack large-scale safety data. While the active hormones are well-understood, the specific combination, dose, or delivery method has not been rigorously tested for long-term safety. |

| Labeling & Warnings | Must include standardized labels, instructions, and a product insert. All systemic estrogen products carry a boxed warning about potential risks like blood clots and certain cancers. | Do not have the same standardized labeling requirements and are not required to carry the FDA’s boxed warnings, even if they contain the same hormones. |

This regulatory divide directly addresses commercial bias by creating two parallel systems. The first is the highly regulated, high-cost path for pharmaceutical companies to bring a standardized product to the national market. The commercial incentive here is the potential for large-scale profit from a patent-protected drug.

The second system, compounding, is designed for patient-specific needs where an FDA-approved drug is not suitable or available. It operates on a smaller, individualized scale. Commercial bias is still present, as compounding pharmacies are for-profit businesses, but it manifests differently ∞ as a response to clinical demand for personalized dosages or combinations that the mass-market system does not provide.

On-Label versus Off-Label Prescribing a Direct Consequence of Policy

The concept of “off-label” use is a direct result of the FDA’s indication-specific approval process. When the FDA approves a drug, it is for the specific use (indication) that was proven in clinical trials. For example, Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) is FDA-approved for men with diagnosed hypogonadism.

However, a licensed physician can legally prescribe an FDA-approved drug for a different purpose if they believe it is medically appropriate for their patient. This is known as off-label prescribing.

This practice is common and essential in medicine, and it plays a huge role in hormone optimization:

- Testosterone for Women ∞ There is currently no FDA-approved testosterone product specifically for women in the United States to treat symptoms like low libido or fatigue. Therefore, when a clinician prescribes a small, carefully monitored dose of testosterone for a female patient, it is an off-label use of a product approved for men.

- Peptide Therapies ∞ Many peptide protocols, such as using Sermorelin or Ipamorelin to stimulate the body’s own growth hormone production, involve prescribing drugs that are FDA-approved for other, often rare, conditions. Their use for anti-aging or performance enhancement is considered off-label.

- Anastrozole in TRT ∞ For men on TRT, the medication Anastrozole is often prescribed to manage estrogen levels. Anastrozole is FDA-approved for treating breast cancer in postmenopausal women, so its use in male TRT protocols is off-label.

Off-label prescribing allows clinicians to apply their expert judgment, using well-understood medications for new purposes based on evolving scientific understanding.

Regulatory policy addresses the potential for commercial bias in off-label use by strictly controlling how pharmaceutical companies can market their products. A company is legally prohibited from promoting or advertising its drug for any off-label use. They cannot provide marketing materials to doctors that discuss unapproved applications.

This “firewall” is intended to ensure that prescribing decisions are driven by the independent medical judgment of the clinician and the needs of the patient, not by a company’s desire to expand its market beyond the scientifically validated indications.

Academic

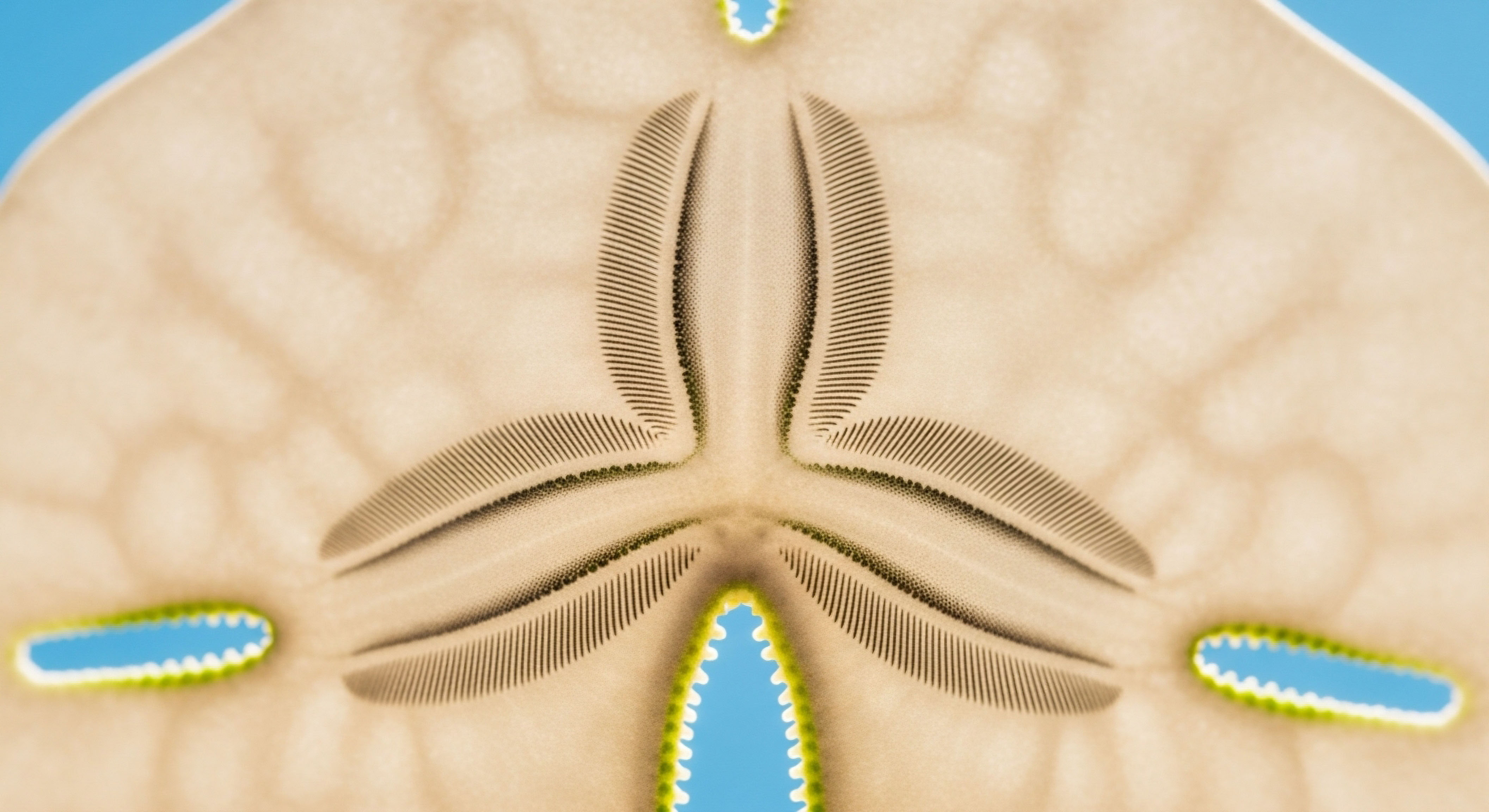

A sophisticated analysis of regulatory policy’s role in mitigating commercial bias in hormone product development requires a systems-level perspective, integrating pharmacology, economics, and clinical science. The Code of Federal Regulations, which governs the FDA, creates an operational framework that is exceptionally well-suited for evaluating single-molecule, single-indication therapeutics.

However, this same framework, when applied to the complex, pleiotropic, and interconnected world of endocrinology, generates significant externalities. These externalities are the very breeding ground for commercial biases that shape the therapeutic landscape in ways that can diverge from optimal patient outcomes.

The foundational economic driver is the patent system, which is designed to incentivize innovation by granting a temporary monopoly. To secure a patent and subsequent market exclusivity, a company must demonstrate novelty. In pharmacology, novelty is most easily and defensibly established with a New Molecular Entity (NME), a synthetic compound not previously approved.

This economic reality creates a powerful current that pulls research and development funding toward synthetic analogues of hormones (which are patentable) and away from investigating new uses or delivery systems for bioidentical hormones (which are not). The regulatory framework, therefore, does not simply evaluate drugs; it actively structures the market and directs the flow of capital and scientific inquiry.

What Is the Impact of Indication-Specific Approval on Systemic Medicine?

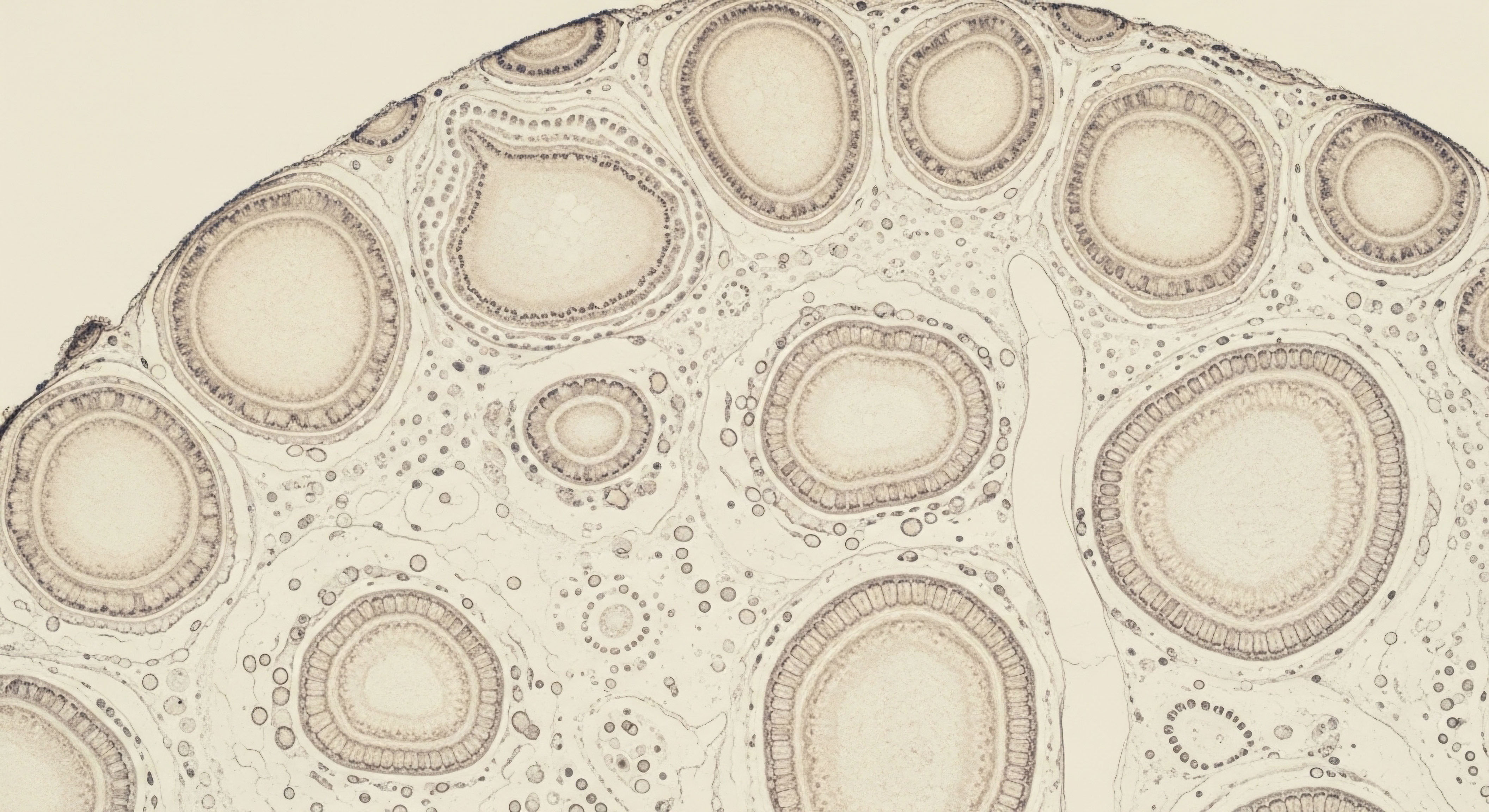

The FDA’s model of indication-specific approval is inherently reductionist. A company must design a Phase III trial with a clearly defined, measurable primary endpoint. For menopausal hormone therapy, a common endpoint is the reduction in the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms.

While this provides a clear metric for success, it commercially disincentivizes the study of other, more systemic effects of hormonal optimization. The potential benefits of testosterone therapy in women on bone density, cognitive function, and metabolic health are scientifically plausible but are harder and more expensive to prove in a clinical trial designed for a single endpoint.

The regulatory structure makes it commercially non-viable for a company to pursue an indication for “enhanced overall well-being” or “restoration of systemic hormonal balance.”

This creates a knowledge gap. A vast body of clinical experience and smaller-scale academic research may point to the systemic benefits of a particular hormonal protocol, but without the financial backing for a pivotal Phase III trial, this knowledge remains outside the sphere of FDA-approved indications. This is where a significant commercial bias emerges ∞ a bias toward easily measurable, symptomatic relief over long-term, systemic health restoration, because the former is more compatible with the regulatory-economic framework.

The reductionist requirements of clinical trials can lead to a focus on treating isolated symptoms rather than addressing the body as an interconnected system.

An Analysis of Bias in Clinical Trial Design and Funding

Regulatory policy attempts to ensure objectivity within clinical trials, but it cannot fully eliminate biases that are embedded in the system before the trial even begins. These biases profoundly influence the evidence base upon which all clinical and regulatory decisions are made.

| Type of Bias | Mechanism and Impact on Hormone Therapy |

|---|---|

| Funding and Sponsorship Bias | Research funded by pharmaceutical companies is more likely to yield results favorable to the sponsor’s product. This is not necessarily due to fraudulent data, but through subtle design choices, such as comparing a new drug to an inappropriate placebo or a suboptimal dose of a competing drug. In endocrinology, this can mean a new synthetic progestin is tested against a placebo, while its comparison to bioidentical progesterone is avoided. |

| Selection and Participation Bias | Historically, clinical trial populations have been homogenous, often excluding women, minorities, and the elderly. This has led to a dearth of high-quality data on hormone therapy in women, particularly concerning testosterone. Regulatory agencies are now pushing for more diverse trial populations, but the legacy of decades of male-centric research still shapes clinical knowledge and approved indications. |

| Endpoint and Outcome Bias | The choice of a primary endpoint can predetermine a trial’s commercial success. A focus on a single biomarker (e.g. LDL cholesterol) or a single symptom (e.g. hot flashes) may cause a drug to be approved while ignoring negative effects on other systems or a lack of benefit in overall quality of life. The systemic, multi-faceted effects of hormones are particularly vulnerable to this type of reductionist evaluation. |

| Publication Bias | Positive and statistically significant trial results are far more likely to be published than negative or inconclusive ones. This skews the available medical literature, creating an inflated sense of efficacy for certain treatments. Regulatory bodies like the FDA have access to all data submitted by a company (positive and negative), but the public and academic discourse can be shaped by what gets published. |

The Case of Compounding and Off-Label Use a Regulatory Release Valve?

The existence and persistence of compounding and off-label prescribing can be viewed as a market and clinical response to the limitations and biases of the mainstream regulatory pathway. When the commercial-regulatory system fails to produce therapies that meet the nuanced needs of individuals ∞ such as a woman requiring a micro-dose of testosterone or a patient needing a preservative-free formulation ∞ compounding pharmacies and off-label prescribing fill the void. This creates a parallel system with a different risk-benefit calculus.

Regulatory policy addresses this by drawing a hard line ∞ it controls commercial speech. A pharmaceutical company cannot promote off-label uses, and a compounding pharmacy cannot make efficacy claims equivalent to an FDA-approved drug. This policy is an attempt to balance patient access and clinical freedom against the risks of using therapies that have not undergone the rigorous vetting of the NDA process.

It is a pragmatic compromise, acknowledging that a single, monolithic regulatory system cannot adequately serve the biological diversity of the entire population. The inherent commercial biases of the primary system make this secondary, more individualized system a clinical necessity.

References

- Santoro, Nanette, et al. “Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy.” Menopause, vol. 27, no. 6, 2020, pp. 620-628.

- “Development & Approval Process | Drugs.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 8 Aug. 2022.

- “How does the FDA approve new drugs?” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 6 Sep. 2023, YouTube.

- Paun, Carmen, and David Lim. “FDA weighs in on gender-affirming care study.” POLITICO, 1 Dec. 2023.

- “Menopause Topics ∞ Hormone Therapy.” The Menopause Society. Accessed July 20, 2024.

- Guyton, Arthur C. and John E. Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 13th ed. Elsevier, 2016.

- Angell, Marcia. The Truth About the Drug Companies ∞ How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It. Random House, 2004.

- Abraham, John. “The pharmaceutical industry as a political player.” The Lancet, vol. 360, no. 9344, 2002, pp. 1498-1502.

Reflection

Charting Your Own Biological Course

The information presented here provides a map of the landscape, showing the forces that shape the hormonal health tools available to you. You have seen how the rigorous, safety-oriented structure of regulatory policy intersects with the powerful currents of commercial interest. This intersection creates the very system through which your health decisions are filtered.

The standardized, FDA-approved protocols offer a foundation of extensively vetted data. The world of specialized, off-label, and compounded therapies offers a path toward greater personalization.

Neither path is inherently superior for every individual. The critical step is to understand the trade-offs each path represents. One prioritizes large-scale, population-level certainty, while the other prioritizes individualized, biologically-specific calibration. Knowing the ‘why’ behind the options your clinician presents is the foundation of true informed consent.

It transforms you from a passive recipient of care into an active, educated partner in your own health journey. What does safety mean to you? How do you weigh the value of large-scale data against your own lived experience? Your answers to these questions will illuminate your personal path toward reclaiming vitality and function.

Glossary

food and drug administration

clinical trials

hormone therapy

new drug application

hormone product development

commercial bias

bioidentical hormones

phase iii trial

fda approval process

regulatory policy

testosterone replacement therapy

off-label prescribing

off-label use