Fundamentals

The feeling is a familiar one. It is the persistent hum of fatigue that sleep does not seem to touch, the mental fog that descends in the middle of a workday, and the quiet, creeping sense of being perpetually overwhelmed.

You may recognize this state as burnout, a term that gives a name to a deeply personal experience of exhaustion. This experience is rooted in the intricate biology of your body, specifically within the delicate communication network of your endocrine system. An employer’s approach to wellness begins with a profound respect for this biological reality. It starts by understanding that the modern work environment, with its unique pressures and physical characteristics, can be a source of significant physiological disruption.

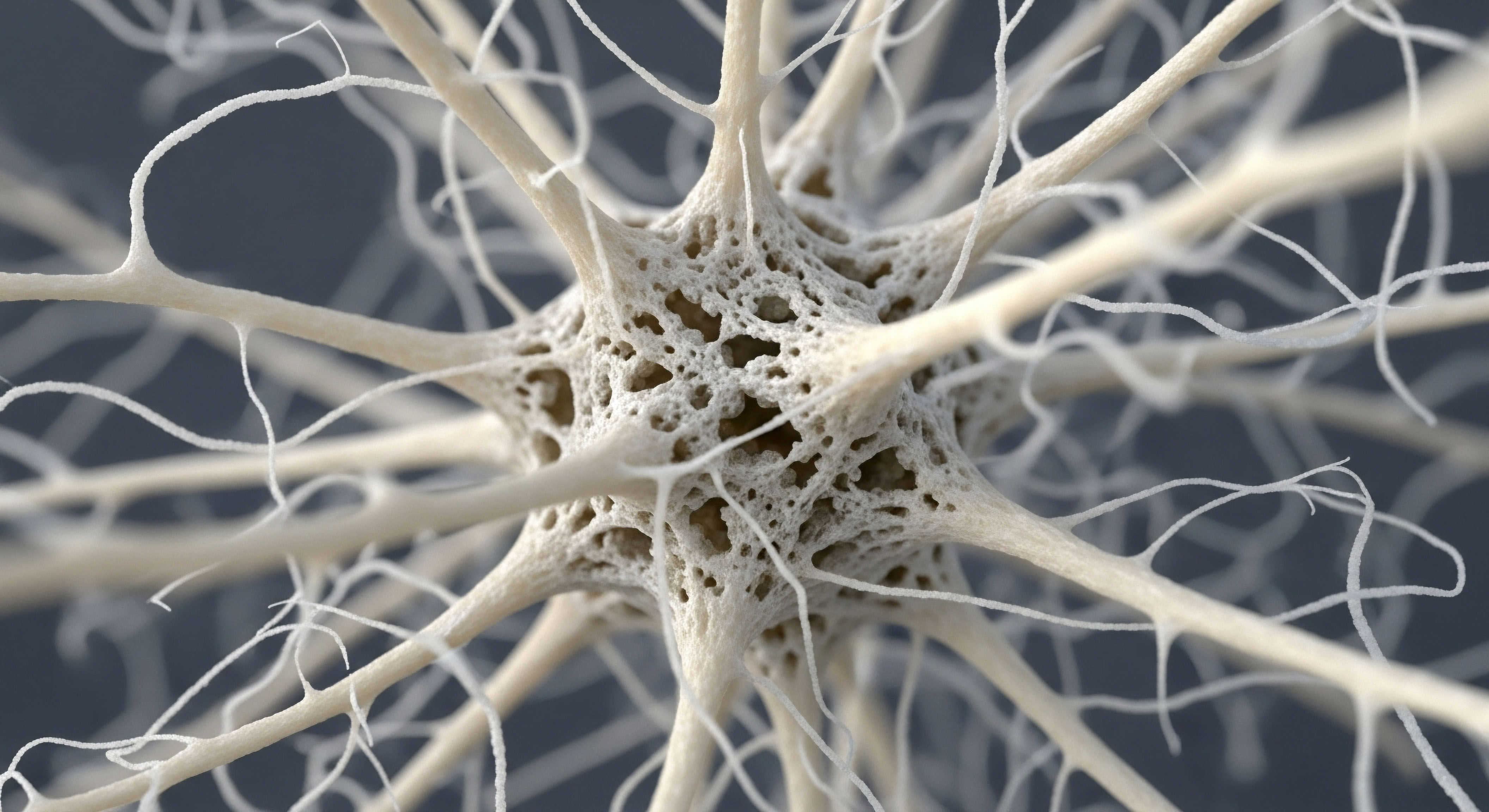

Your body is equipped with a masterful system for managing challenges, known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. Think of it as your internal crisis management team. When you perceive a stressor, like an urgent project deadline or a difficult professional interaction, your hypothalamus sends a signal to your pituitary gland, which in turn signals your adrenal glands to release cortisol.

This hormone is a powerful ally in the short term, mobilizing energy and increasing focus. The system is designed for acute, episodic activation. The architecture of many contemporary workplaces, however, subjects this system to relentless, low-grade activation. This chronic signaling keeps cortisol levels persistently elevated, which can lead to a cascade of downstream effects, including impaired immune function, metabolic disturbances, and eventually, a state of profound exhaustion as the system struggles to maintain its output.

A truly health-supportive workplace is built upon the principle of respecting and protecting the employee’s underlying physiological systems.

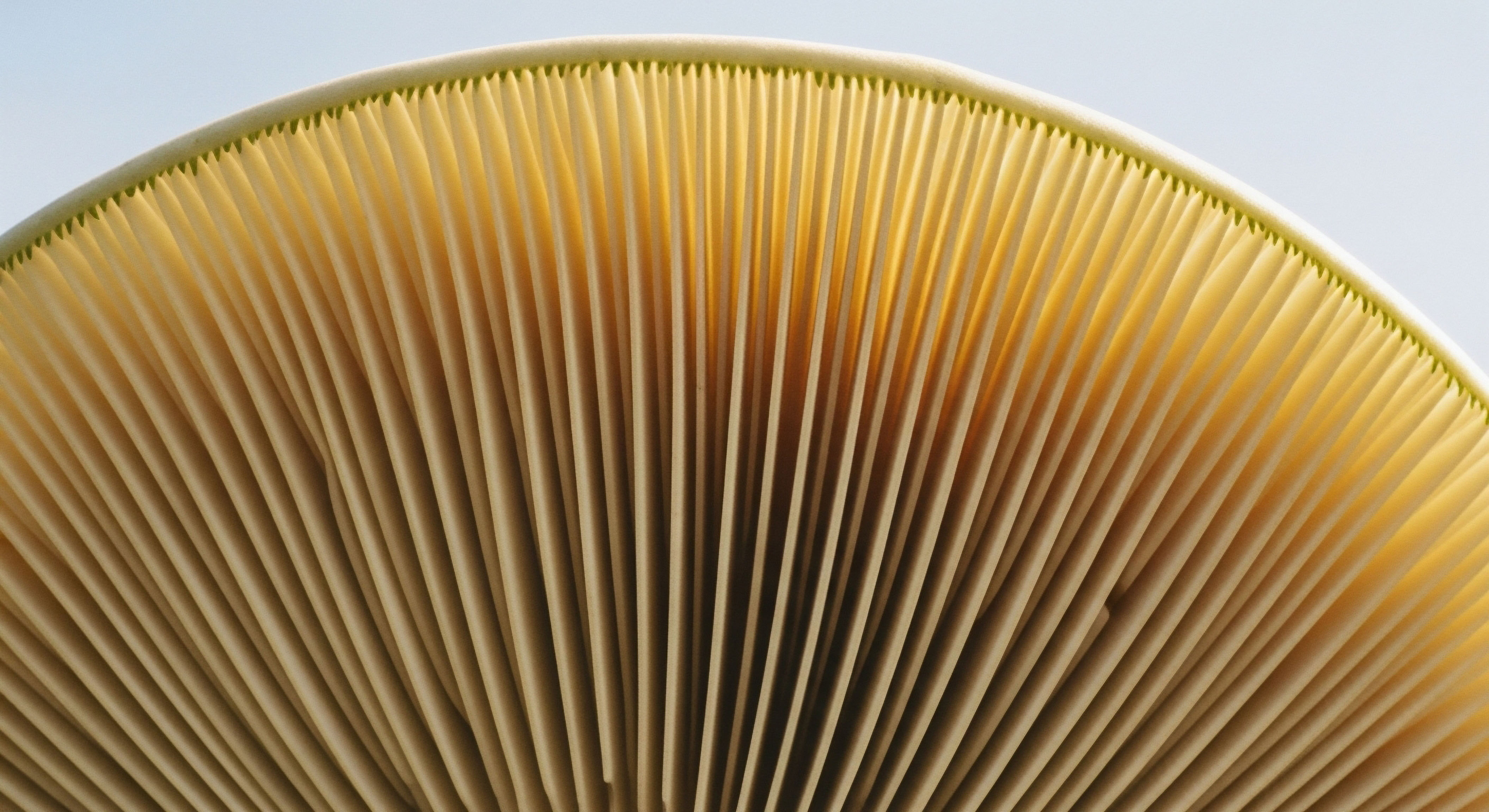

Parallel to the HPA axis, your body operates on a fundamental, 24-hour cycle known as the circadian rhythm. This internal clock, governed by a master pacemaker in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), orchestrates nearly every biological process, from sleep-wake cycles to hormone release and metabolism.

Its primary environmental cue is light. The bright, blue-spectrum light emitted by screens and standard office lighting throughout the day sends a constant “daytime” signal to your brain. Exposure to this light, especially late into the workday, actively suppresses the production of melatonin, the hormone that signals the onset of night and prepares your body for restorative sleep.

This desynchronization between your internal clock and your daily life contributes directly to poor sleep quality, which further dysregulates cortisol rhythms and impacts the hormones that control appetite and energy balance.

The Sedentary Architecture of Modern Work

The third critical element is movement, or the lack thereof. The human body is engineered for motion. Prolonged periods of sitting, a hallmark of office-based work, represent a significant departure from our biological design. When you are sedentary, the large muscles of your lower body are inactive, which has immediate metabolic consequences.

Lipoprotein lipase, an enzyme crucial for breaking down fats in the blood, becomes less active. Over time, this contributes to unhealthy lipid profiles and diminished insulin sensitivity, where your cells become less responsive to the hormone insulin.

This state, known as insulin resistance, is a direct precursor to metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that includes high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and excess body fat around the waist. An employer’s role in fostering wellness extends to the very physical layout of the workspace, creating an environment that invites movement and counteracts the powerful metabolic drag of a sedentary workday.

Understanding these three biological systems ∞ the HPA axis, the circadian rhythm, and metabolic regulation ∞ provides a new lens through which to view workplace wellness. It moves the conversation from generic programs to a specific, science-based approach.

A culture of wellness is one where the organizational structure, the physical environment, and the daily expectations are designed to protect and support these fundamental physiological processes. It is an acknowledgment that an employee’s ability to thrive, innovate, and contribute is inextricably linked to their biological integrity.

Intermediate

Creating a workplace that genuinely supports employee health Meaning ∞ Employee Health refers to the comprehensive state of physical, mental, and social well-being experienced by individuals within their occupational roles. requires a deliberate architectural approach, one that engineers the environment and operational dynamics to align with human physiology. This involves moving beyond reactive wellness initiatives and instead proactively structuring the workday to buffer the endocrine and metabolic systems from chronic strain. The pillars of such a culture are built on the clinical understanding of stress, light, and movement, translating scientific principles into tangible workplace practices.

How Can Workload Design Protect the HPA Axis?

The persistent activation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is a primary driver of burnout. An employer can directly mitigate this by focusing on the sources of chronic stress. This involves a critical examination of workload, autonomy, and psychological safety.

Work that is consistently overwhelming, coupled with a lack of control over one’s tasks and deadlines, creates a potent recipe for uncontrollable stress. This specific type of stress has been shown to be particularly damaging, impairing the function of the prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for executive functions like decision-making and emotional regulation. A culture of wellness, therefore, begins with intelligent work design.

- Autonomy and Control ∞ Granting employees significant autonomy in how they approach their work and manage their time can shift a stressor from uncontrollable to controllable. This single psychological shift can dramatically alter the physiological response, reducing the magnitude of the cortisol surge and its downstream effects.

- Predictability and Clarity ∞ Ambiguity about roles, expectations, and performance metrics is a significant source of low-grade, chronic anxiety. Establishing clear communication channels and predictable workflows helps to create a psychologically safe environment, minimizing the constant vigilance that keeps the HPA axis on high alert.

- Sustainable Workloads ∞ The expectation of constant availability and the normalization of excessive hours directly antagonize the body’s need for recovery. True wellness cultures implement and respect boundaries, ensuring that workloads are challenging yet manageable, and that periods of intense effort are followed by genuine opportunities for rest and physiological reset.

Structuring the Day around Circadian Principles

The modern office is often a circadian nightmare, with uniform, blue-toned artificial light from morning until evening. An employer can foster wellness by becoming a steward of the circadian clock. This is achievable through intelligent lighting design and the promotion of routines that honor the body’s natural light-dark cycle.

Exposure to natural light during the day is critical for anchoring the circadian rhythm Meaning ∞ The circadian rhythm represents an endogenous, approximately 24-hour oscillation in biological processes, serving as a fundamental temporal organizer for human physiology and behavior. and promoting alertness. Workplaces can be designed with this in mind, maximizing window access and creating outdoor spaces for breaks. As the day progresses, the spectrum of light should ideally shift.

Advanced, biodynamic lighting systems can mimic the natural progression of sunlight, transitioning from cooler, blue-enriched light in the morning to warmer, amber tones in the afternoon. This helps to reduce the melatonin-suppressing effects of artificial light as the body prepares for evening. Furthermore, establishing cultural norms that discourage late-night emails and encourage “digital sunsets” can help employees protect their evening wind-down period, which is essential for robust melatonin production and high-quality, restorative sleep.

A workspace designed with circadian health in mind uses light as a tool to synchronize internal biology with the demands of the workday.

The following table illustrates the contrasting effects of a standard versus a circadian-aligned office environment:

| Environmental Factor | Standard Office Environment | Circadian-Aligned Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Lighting |

Uniform, high-intensity, blue-spectrum light throughout the day. |

Maximizes natural light; uses biodynamic lighting that shifts from cool to warm tones. Encourages screen-dimming software in the late afternoon. |

| Work Schedule |

Rigid 9-to-5 schedule with pressure for late-night availability. |

Flexible schedules that allow for morning light exposure; cultural norms that protect evening hours from work demands. |

| Physiological Impact |

Suppressed daytime cortisol peak, blunted evening melatonin onset, leading to sleep latency and poor sleep quality. |

Robust morning cortisol awakening response, strong melatonin signal in the evening, leading to better sleep consolidation and hormonal regulation. |

Fostering a Metabolically Healthy Workspace

An employer can combat the metabolic consequences of a sedentary work culture by weaving opportunities for movement into the very fabric of the workday. This goes far beyond subsidized gym memberships, which are often utilized by those who are already active. The goal is to reduce overall sedentary time for everyone.

Providing sit-stand desks is a foundational step, allowing employees to change their posture throughout the day. This simple act of standing engages muscles and can help mitigate the drop in lipoprotein lipase activity associated with prolonged sitting.

The culture can further support this through practices like “walking meetings” for small group discussions and designing office layouts that require short walks to access printers, water coolers, or collaborative spaces. Encouraging micro-breaks for stretching and movement every hour can also be highly effective. These interventions collectively work to improve insulin sensitivity and promote better metabolic health, directly countering the risks of metabolic syndrome Meaning ∞ Metabolic Syndrome represents a constellation of interconnected physiological abnormalities that collectively elevate an individual’s propensity for developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. that are so prevalent in office-based populations.

Academic

The ultimate physiological endpoint of a work culture that disregards biological limits is a state of profound systemic dysregulation. From a clinical perspective, the concept of burnout can be understood as the organism’s adaptive, yet ultimately maladaptive, response to chronic, unmitigated stress.

This response culminates in a phenomenon known as glucocorticoid receptor Meaning ∞ The Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) is a nuclear receptor protein that binds glucocorticoid hormones, such as cortisol, mediating their wide-ranging biological effects. (GR) resistance, a cellular state with far-reaching implications for an individual’s neuroendocrine, metabolic, and immune health. An employer’s highest calling in fostering wellness is to create an environment that prevents the very development of this pathological state.

The Pathophysiology of Glucocorticoid Receptor Resistance

The glucocorticoid receptor is the protein within every cell that binds to cortisol and translates its message into a genomic response. In a healthy system, cortisol binds to the GR, and the complex translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene expression, which includes a powerful negative feedback loop that signals the HPA axis Meaning ∞ The HPA Axis, or Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, is a fundamental neuroendocrine system orchestrating the body’s adaptive responses to stressors. to turn off.

This maintains homeostasis. Under conditions of chronic stress, as is common in high-pressure work environments, the perpetual torrent of cortisol leads to a protective downregulation at the cellular level. The cells, in an attempt to shield themselves from overstimulation, reduce the number of glucocorticoid receptors or decrease their binding affinity. This is GR resistance. The cell effectively becomes “deaf” to cortisol’s signal.

This creates a paradoxical and clinically challenging situation. The HPA axis, sensing that its signal is not being received, continues to secrete high levels of cortisol in an attempt to overcome the resistance.

Lab results may show normal or even high circulating cortisol, yet the individual experiences the functional symptoms of cortisol deficiency ∞ profound fatigue, widespread inflammation (as cortisol’s anti-inflammatory effects are blunted), cognitive dysfunction or “brain fog,” and increased susceptibility to illness. The system is stuck in a state of high-effort, low-impact signaling, which is the biological signature of burnout.

Glucocorticoid receptor resistance represents the cellular mechanism through which chronic workplace stress translates into systemic illness.

What Are the Neurobiological Consequences of Chronic Stress?

This state of GR resistance and HPA axis dysfunction Meaning ∞ HPA Axis Dysfunction refers to impaired regulation within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, a central neuroendocrine system governing the body’s stress response. exacts a heavy toll on the central nervous system. The brain is a primary target of glucocorticoids, and chronic exposure, particularly in a state of receptor resistance, leads to structural and functional remodeling of key brain regions.

- The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) ∞ This region, essential for executive functions such as planning, working memory, and impulse control, is highly sensitive to stress. Chronic glucocorticoid exposure has been shown to cause dendritic retraction and a loss of synaptic connections in the PFC. This anatomical change manifests as the cognitive deficits seen in burnout ∞ difficulty concentrating, impaired decision-making, and reduced mental flexibility.

- The Amygdala ∞ In contrast to the PFC, the amygdala, the brain’s fear and emotional processing center, undergoes dendritic growth and becomes hyper-responsive. This leads to a state of heightened anxiety, emotional reactivity, and a bias toward perceiving threats in the environment. The weakened PFC is less able to exert top-down control over the hyperactive amygdala, resulting in the emotional dysregulation characteristic of burnout.

- The Hippocampus ∞ This structure is critical for learning and memory and is also dense with glucocorticoid receptors. Chronic stress impairs neurogenesis in the hippocampus and can lead to a reduction in its volume. This contributes to the memory problems often reported by individuals experiencing burnout.

The following table details the neuroanatomical changes associated with chronic workplace stress Meaning ∞ Workplace stress denotes a state of physiological and psychological strain arising when perceived demands of the professional environment exceed an individual’s perceived coping resources, leading to an adaptive response involving neuroendocrine activation. and their functional implications.

| Brain Region | Neurobiological Change | Functional Consequence in the Workplace |

|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex |

Dendritic retraction; reduced synaptic density; functional impairment. |

Impaired strategic planning, poor decision-making, difficulty with complex problem-solving, reduced focus. |

| Amygdala |

Dendritic growth; hyperactivity; strengthened connections to fear pathways. |

Increased anxiety, heightened emotional reactivity, poor interpersonal interactions, perception of a hostile work environment. |

| Hippocampus |

Reduced neurogenesis; potential volume reduction. |

Difficulty learning new information, impaired short-term memory recall, reduced ability to adapt to new procedures. |

An Environment That Prevents Systemic Breakdown

From this academic, systems-biology perspective, a true culture of wellness is a culture of prevention. It is an environment architected to prevent the slide into HPA axis dysfunction and GR resistance.

While an employer cannot prescribe clinical interventions like Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT) for men experiencing stress-induced hypogonadism, or Growth Hormone Peptide Therapy for individuals seeking to repair the metabolic damage of a sedentary job, it can create conditions that protect the integrity of these systems in the first place.

A workplace that minimizes chronic, uncontrollable stress, respects circadian biology, and promotes physical activity is one that reduces the allostatic load Meaning ∞ Allostatic load represents the cumulative physiological burden incurred by the body and brain due to chronic or repeated exposure to stress. on the entire endocrine system. This makes an individual’s own biological systems more resilient and ensures that if they do require clinical support like hormonal optimization protocols, those treatments are being introduced into a less hostile physiological environment, increasing their potential for success. The ultimate responsibility of an employer is to provide a workplace that does no biological harm.

References

- Eddy, M. D. & Schou, P. (2023). A Systematic Review and Revised Meta-analysis of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model of Workplace Stress and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Measures of Stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 85(5), 446 ∞ 457.

- Michels, N. & Clays, E. (2021). The Neurobiology of Burnout ∞ A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6025.

- Oakley, R. H. & Cidlowski, J. A. (2013). The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor ∞ new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 132(5), 1033 ∞ 1044.

- Arnsten, A. F. (2021). Physician Distress and Burnout ∞ The Neurobiological Perspective. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 96(3), 763-769.

- Choi, D. W. et al. (2019). The Effects of Artificial Light at Night on Human Health ∞ A Literature Review of Observational and Experimental Studies. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 34(32), e207.

- Edwardson, C. L. et al. (2012). Association of Sedentary Behaviour with Metabolic Syndrome ∞ A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 7(4), e34916.

- Banken, E. et al. (2018). The role of the glucocorticoid receptor in metabolism ∞ from physiology to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1410(1), 32-47.

- Pariante, C. M. (2017). The glucocorticoid receptor ∞ part of the solution, part of the problem. The Journal of psychopharmacology, 31(10), 1271 ∞ 1276.

- Wright, K. P. Jr, et al. (2013). Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Current Biology, 23(16), 1554 ∞ 1558.

- Nicolaides, N. C. et al. (2019). Primary Generalized Glucocorticoid Resistance Syndrome. In Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Environment

The information presented here provides a biological framework for understanding the profound connection between your work environment and your personal vitality. It translates the subjective feelings of fatigue, fogginess, and being overwhelmed into the objective language of cellular biology, hormonal axes, and neural pathways. This knowledge is a tool.

It shifts the perspective from one of passive endurance to one of active awareness. Consider the rhythms of your own workday. Where are the points of friction between your environment and your biology? Think about the quality of light in your workspace, the duration of your sedentary periods, and the nature of the demands placed upon you.

This understanding is the first step in a personal health journey. It allows you to identify the specific environmental inputs that may be taxing your system. Recognizing that the midafternoon slump is not a personal failing but a potential consequence of circadian disruption or metabolic slowdown empowers you to make small, informed adjustments.

The path to reclaiming your vitality is one of self-observation and precise, personalized action. The goal is to consciously architect your daily routines to support your underlying physiology, creating an internal environment where your systems can function with efficiency and resilience.